Photo by Fred Kearney on Unsplash, CC BY-SA

Emmett Stinson, Deakin University

There has been no shortage of bad news for Australia’s literary and publishing sector in the last year. Major literary journals Island and Overland have been defunded. Only 2.7% of Australia Council funding went to books and writing. The Chair in Australian Literature at University of Sydney is not being renewed.

Two major projects by literary academics were recommended for funding by the Australian Research Council’s peer-review process in 2018, but were rejected by ministerial discretion. Melbourne University Publishing’s CEO, Louise Adler, resigned after the university asked for a change in editorial direction.

And now University of Western Australia has announced dramatic changes to its highly-decorated press, University of Western Australia Publishing. These changes involve not renewing the contract of Director Terri-ann White, deemed “surplus to requirements”, and an end to current publishing activities.

It would be hard to blame writers and literary academics for feeling paranoid. Just because you’re paranoid, it doesn’t mean they’re not out to get you.

A decline in literary publishing

In 2006, Mark Davis published The Decline of the Literary Paradigm in Australian Publishing.

He argued that between WWII and the 1990s, Australian publishers embraced their role in shaping national culture by subsidising unprofitable literary works with profits from more commercial titles. But by the 2000s, publishers had become neoliberal organisations that sought to maximise profits rather than support literary culture.

We are now seeing this same logic applied by universities.

Universities are increasingly focused on metrics driving enrolments, international rankings and research excellence. This, in turn, supports government funding and research grant income. Universities increasingly prioritise these metrics over cultural contributions that are harder to quantify.

Read more:

Why Australia needs a new model for universities

A statement released by UWA claims the changes will help “to guarantee modern university publishing into the future”, foreshadowing “a mix of print, greater digitisation and open access publishing.”

This statement might appear to mirror recent events at Melbourne University Press last year, but these situations are very different.

A leading literary publisher

Academics had long questioned Melbourne University Press’ publication of works with commercial and political appeal but no clear scholarly or cultural value.

Professor Ronan McDonald summed up this view earlier this year when he wrote that Melbourne University Press was “a trade press irritatingly obliged to publish a few academic titles”.

Melbourne University reaffirmed its commitment to the Press by hiring a respected scholarly publisher, founding director of Monash University Publishing Nathan Hollier, with a track record of producing scholarly titles alongside prize-winning works for a general readership.

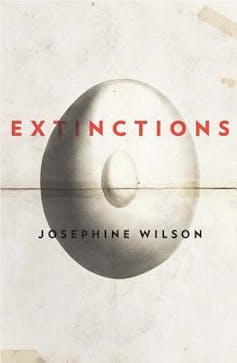

UWA Publishing, on the other hand, is one of our leading literary publishers, cultivating authors and significant titles often overlooked by commercial publishers.

It published Josephine Wilson’s Extinctions, which won the Miles Franklin Award in 2017; is one of Australia’s foremost publishers of poetry; and has published scholarly works by leading Australian humanities academics, such as John Frow, Ross Gibson, and Ken Gelder. It has also published a series of traditional Noongar stories retold by the award-winning author Kim Scott

It has always balanced commitments to scholarly publishing with a significant literary list.

Open access university presses: a failed experiment

The notion that a respected publishing house can be replaced by open access publishing is disproved by examining other Australian university presses, such as the now-closed University of Adelaide Press, founded in 2009 with a mission to be an open access publisher.

While the press generated many interesting titles, it failed to have a cultural impact. Open access enables free and easy dissemination of work, but this does not meant that it engages with literary culture. Scholars can access works freely, but titles are isolated from bookshops, reviews, and cultural conversations.

Sydney University Press, which was relaunched in 2003 after closing in 1987, has employed a “hybrid approach” to open access. It is now returning to a more standard university publishing model, establishing a research series with dedicated editorial boards of academics, and even publishing a novel, Joshua Lobb’s The Flight of Birds, shortlisted for the Readings New Fiction Prize in 2019.

Open access has an important role to play in academic publishing, but it is laughable to claim UWA Publishing’s cultural impact can simply be replaced through open access.

Can it be saved?

There is a campaign underway to save UWA Publishing, including a petition with over 6,000 signatures.

It is hard to know at this stage if it will have any effect. It may be the publishing house is the victim of larger financial pressures currently affecting University of Western Australia.

This, of course, is the problem for the literary sector more generally: when cuts are needed, literature is always first on the chopping block.![]()

Emmett Stinson, Lecturer in Writing and Literature, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.