Simone Padovani/Awakening/Getty Images

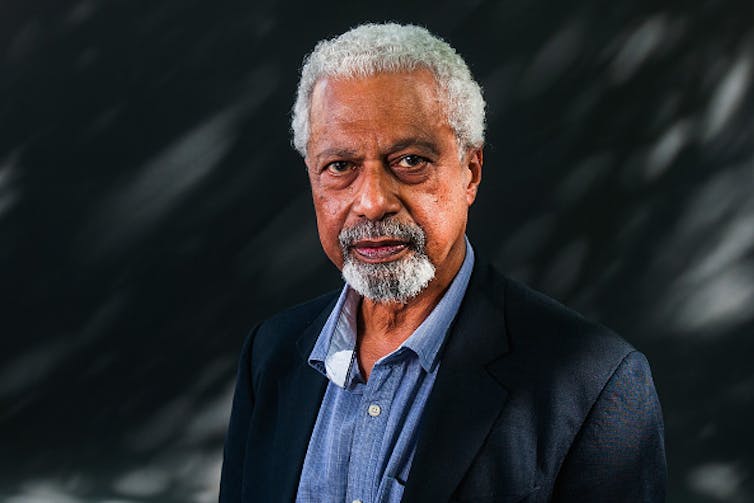

Lizzy Attree, Richmond American International UniversityThe Nobel Prize in Literature, considered the pinnacle of achievement for creative writers, has been awarded 114 times to 118 Nobel Prize laureates between 1901 and 2021. This year it went to novelist Abdulrazak Gurnah, who was born in Zanzibar, the first Tanzanian writer to win. The last black African writer to win the prize was Wole Soyinka in 1986. Gurnah is the first black writer to win since Toni Morrison in 1993. Charl Blignaut asked Lizzy Attree to describe the winner and share her views on his literary career.

Who is Gurnah and what is his place in East African literature?

Abdulrazak Gurnah is a Tanzanian writer who writes in English and lives and works in the UK. He was born in Zanzibar, the semi-autonomous island off the east African coast, and studied at Christchurch College Canterbury in 1968.

Zanzibar underwent a revolution in 1964 in which citizens of Arab origin were persecuted. Gurnah was forced to flee the country when he was 18. He began to write in English as a 21-year-old refugee in England, although Kiswahili is his first language. His first novel, Memory of Departure, was published in 1987.

He has written numerous works that pose questions around ideas of belonging, colonialism, displacement, memory and migration. His novel Paradise, set in colonial east Africa during the first world war, was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 1994.

Comparable to Moyez G. Vassanji, a Canadian author raised in Tanzania, whose attention focuses on the east African Indian community and their interaction with the “others”, Gurnah’s novel Paradise deploys multi-ethnicity and multiculturalism on the shores of the Indian Ocean from the perspective of the Swahili elite.

A distinguished academic and critic, he recently sat on the board of the Mabati Cornell Kiswahili Prize for African literature and has served as a contributing editor for the literary magazine Wasafiri for many years.

He is currently Professor Emeritus of English and Postcolonial Literatures at the University of Kent, having retired in 2017.

Why is Gurnah’s work being celebrated – what is powerful about it?

He was awarded the Nobel

for his uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fates of the refugee in the gulf between cultures and continents.

He is one of the most important contemporary postcolonial novelists writing in Britain today and is the first black African writer to win the prize since Wole Soyinka in 1986. Gurnah is also the first Tanzanian writer to win.

Photo by TOLGA AKMEN/AFP via Getty Images

His most recent novel, Afterlives, is about Ilyas, who was taken from his parents by German colonial troops as a boy and returns to his village after years of fighting against his own people. The power in Gurnah’s writing lies in this ability to complicate the Manichean divisions of enemies and friends, and excavate hidden histories, revealing the shifting nature of identity and experience.

What Gurnah work stands out for you and why?

The novel Paradise stands out for me because in it Gurnah re-maps Polish-British writer Joseph Conrad’s 19th century journey to the “heart of darkness” from an east African position going westwards. As South African scholar Johan Jacobs has said, he

reconfigures the darkness at its heart … In his fictional transaction with Heart of Darkness, Gurnah shows in Paradise that the corruption of trade into subjection and enslavement pre-dates European colonisation, and that in East Africa servitude and slavery have always been woven into the social fabric.

The tale is narrated so gently by 12-year-old Yusuf, lovingly describing gardens and assorted notions of paradise and their corruption as he is pawned between masters and travels to different parts of the interior from the coast. Yusuf concludes that the brutality of German colonialism is still preferable to the ruthless exploitation by the Arabs.

Like Achebe in Things Fall Apart (1958), Gurnah illustrates east African society on the verge of huge change, showing that colonialism accelerated this process but did not initiate it.

Is the Nobel literature prize still relevant?

It’s still relevant because it is still the biggest single prize purse for literature around. But the method of selecting a winner is fairly secretive and depends on nominations from within the academy, meaning doctors and professors of literature and former laureates. This means that although the potential nominees are often discussed in advance by pundits, no-one actually knows who is in the running until the prize winner is announced. Ngugi wa Thiong’o, for example, is a Kenyan writer whom many believe should have won by now, along with a number of others like Ivan Vladislavic from South Africa.

Winning puts a global spotlight on a writer who has often not been given full recognition by other prizes, or whose work has been neglected in translation, thus breathing new life into works that many have not read before and deserve to be read more widely.![]()

Lizzy Attree, Adjunct Professor, Richmond American International University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.