The link below is to an article that takes a look at book subscription services.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/best-book-subscriptions/

The link below is to an article that takes a look at book subscription services.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/best-book-subscriptions/

Jessica Gannaway, University of Melbourne and Melitta Hogarth, University of Melbourne

This article is part of three-part series on summer reads for young people after a very unique year.

US teenager Trayvon Martin was shot dead in 2012 by a neighbourhood watch volunteer, George Zimmerman who was later acquitted of the murder. This saw the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement. The racist social and political issues in the US saw the deaths and violence on Black bodies brought front and centre through acts of protest.

The arguments against the alleged police brutality in the US were easily translatable to the Australian context.

The Black Lives Matters movement was renewed following the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police officers in May this year. And together with US counterparts, tens of thousands of Australians marched across our cities to draw attention to racial profiling, police brutality and the more than 400 Indigenous people who have died in police custody since a royal commission into the problem was held in 1991.

The global movement brought unprecedented sales of books about race and anti-racism. This turn toward texts is indicative of the role they play in helping us make sense of major social issues.

Angie Thomas, author of the 2017 bestseller “The Hate U Give”, has spoken about the role of literature in igniting awareness, resistance and change.

I think books […] play a huge role in opening people’s eyes and they’re a form of activism in their own right, in the fact that they do empower people and show others the lives of people who may not be like themselves.

Research has long shown a link between the books we read and our development of empathy. But more recent research has highlighted it is important we don’t see books as immediate fixes to complex social issues, especially when we import these books from other locations and times.

Our reading must be accompanied by close attention to the ways racism and prejudice unfold in our own location.

Read more:

5 Australian books that can help young people understand their place in the world

Coming to understand the impact and complexity of racism in this way is referred to as “racial literacy”. Here are five books that can help young people build racial literacy around the varied forms of racism and discrimination.

by Nic Stone

Dear Martin explores issues of race through the eyes of conscientious 17 year old, Justyce McAllister.

Built around the central question, “What would Martin (Luther King) do?”, this novel brings to light the litany of decisions and ethical conundrums thrust into Justyce’s lap daily, as he navigates a world affected by racism and prejudice.

by Ibi Zobai and Yusuf Salaam

In 1989, five young men were falsely accused of the assault and murder of a jogger in New York’s Central Park. Now documented in Ava Duvernay’s Neflix miniseries When They See Us, the Five were exonerated 12 years later.

But the story stands as a haunting reminder of the inequalities experienced by Black men and the life-altering consequences this can wreak on innocent lives.

One of these young men, Yusuf Salaam, collaborates with award-winning author and prison reform activist Ibi Zobai, to craft a story that examines these themes through a narrative of a wrongfully incarcerated young man navigating his teenage years in prison.

edited by Anita Heiss

This anthology of 50 chapters provides an opportunity to deeply listen and understand the lived experiences of Indigenous Australians and the ways racism takes all manner of overt, subtle and systemic forms.

Particularly noteworthy are the chapters by Ambelin Kwaymullina and Celeste Liddle, in which the authors describe both the nature of racism experienced by them from the schoolyard, and the broader historical context on which this racism is based.

by Brittney Morris

This novel centres on 17-year-old Kiera, a talented young developer who creates a multiplayer role-playing game. The game is a “mecca of black excellence” and an escape from the racism often experienced by those “game-playing while black”.

When an offline murder is traced back to the game, Kiera grapples with the complexity of both the implications of her creation and the conversations it triggers.

Slay weaves social commentary into the dialogue between characters from all walks of life, covering everything from cultural appropriation, to whether racism can ever be “reversed”.

by Ambelin Kwaymullina

Many books here centre around the kind of racial stereotyping and violence that put the Black Lives Matter movement on the map. But understanding racism in the Australian context also involves examining colonialism and the racist underpinnings of our history.

Living on Stolen Land centres Indigenous sovereignty in the conversation about race. Using prose verses such as those titled “Bias” and “Listening”, it leads readers through examining unconscious beliefs and moving toward being a genuine ally of Indigenous people.

Author and educator Layla F Saad has suggested when we read texts about social issues like racism, we read for transformation, not merely information.

A range of texts have been developed to support families in having these transformative discussions together. Maxine Beneba Clarkes’ “When We Say Black Lives Matter”, for instance, is a beautifully illustrated picture book that focuses on the strength and resilience of black children and communities. While texts like Our Home our Heartbeat by Adam Briggs centres on key Indigenous figures to be celebrated.

Read more:

Teen summer reads: 5 novels to help cope with adversity and alienation

![]()

Jessica Gannaway, Lecturer, University of Melbourne and Melitta Hogarth, Assistant Dean Indigenous/ Senior lecturer, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Lucy Montgomery, Curtin University

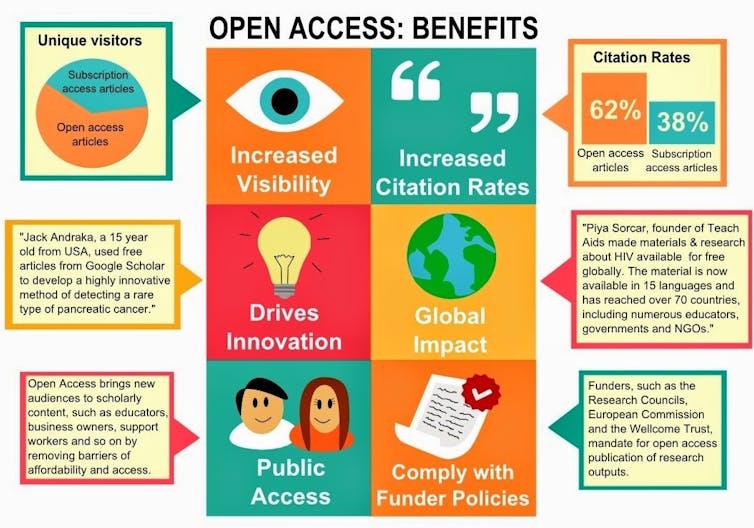

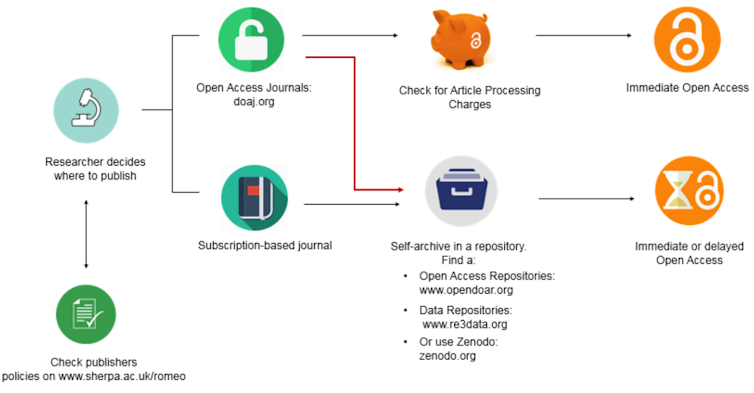

For all its faults, 2020 appears to have locked in momentum for the open access movement. But it is time to ask whether providing free access to published research is enough – and whether equitable access to not just reading but also making knowledge should be the global goal.

In Australia the first challenge is to overcome the apathy about open access issues. The term “open access” has been too easy to ignore. Many consider it a low priority compared to achievements in research, obtaining grant funding, or university rankings glory.

But if you have a child with a rare disease and want access to the latest research on that condition, you get it. If you want to see new solutions to climate change identified and implemented, you get it. If you have ever searched for information and run into a paywall requiring you to pay more than your wallet holds to read a single journal article that you might not even find useful, you will get it. And if you are watching dire international headlines and want to see a rapid solution to the pandemic, you will probably get it.

Many publishing houses temporarily threw open their paywall doors during the year. Suddenly, there was free access to research papers and data for scholars researching pandemic-related issues, and also for students seeking to pursue their studies online across a range of disciplines.

In October 2020, UNESCO made the case for open access to enhance research and information on COIVD-19. It also joined the World Health Organisation and UN High Commissioner for Human Rights in calling for open science to be implemented at all stages of the scientific process by all member states.

There is clearly an appetite for freely available information. Since it was established earlier this year, the CORD-19 website has built up a repository of more than 280,000 articles related to COVID-19. These have attracted tens of millions of views.

Europe was already ahead of the curve on open access and 2020 has accelerated the change. Plan S is an initiative for open access launched in Europe in 2018. It requires all projects funded by the European Commission and the European Research Council to be published open access.

Read more:

All publicly funded research could soon be free for you, the taxpayer, to read

A 2018 report commissioned by the European Commission found the cost to Europeans of not having access to FAIR (findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable) research data was €10 billion ($A16.1 billion) a year.

In 2019, open access publications accounted for 63% of publications in the UK, 61% in Sweden and 54% in France, compared to 43% of Australian publications.

Australia’s flagship Australian Research Council has required all research outputs to be open access since 2013. But researchers can choose not to publish open access if legal or contractual obligations require otherwise. This caveat has led to a relatively low rate of open access in Australia.

Read more:

Universities spend millions on accessing results of publicly funded research

The Council of Australian University Librarians (CAUL) and the Australasian Open Access Strategy Group (AOASG) have long carried the torch for open access in Australia. But, without levers to drive change, they have struggled to change entrenched publishing practices of Australian academics.

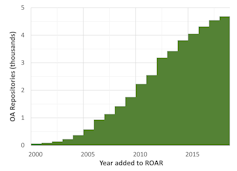

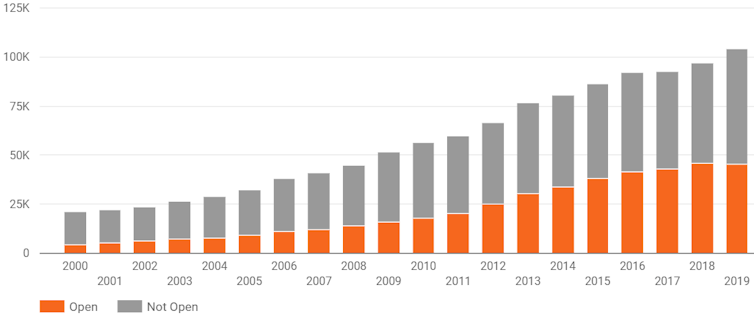

Our Curtin Open Knowledge Initiative (COKI) project has examined open access across the world. We have analysed open access performance of individuals, individual institutions, groups of universities and nations in recent decades. The COKI Open Access Dashboard offers a glimpse into a subset of this international data, providing insights into national open access performance.

This analysis shows a steady global shift towards open access publications.

For example, in November 2020, Springer Nature announced it would allow authors to publish open access in Nature and associated journals at a price of up to €9,500 (A$15,300) per paper from January 2021. This was a signal change for the publishing industry. One of the world’s most prestigious journals is overturning decades of closed-access tradition to throw open the doors, and committing to increasing its open access publications over time.

At the moment, the pricing of this model enables only a select group to publish open access. The publication cost is equivalent to the value of some Australian research grants. Pricing is expected to become more affordable over time.

Read more:

Increasing open access publications serves publishers’ commercial interests

This international trend is a positive step for fans of freely available facts. However, we should not lose sight of other potentially larger issues at play in relation to open knowledge – that is, a level playing field for access to both published research and participation in research production.

Put another way, we need to pursue not only equity among knowledge takers but also among knowledge makers if we are to enable the world’s best thinkers to collaborate on the planet’s signature challenges.

All of this is good news for people who love to access information – but the bigger overall question for the higher education sector is about the conventions, traditions and trends that determine who gets to be considered for a job in a lab or a library or a lecture theatre. There is much more to be done to make our universities open for all – a future of equity in knowledge making as well as taking.![]()

Lucy Montgomery, Program Lead, Innovation in Knowledge Communication, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article reporting on the shortlists for the 2021 Victorian Premier’s Literary Awards.

For more visit:

https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2020/12/08/160636/victorian-premiers-literary-awards-2021-shortlists-announced/

Tatiana Bobkova/Shutterstock

Peter Martin, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

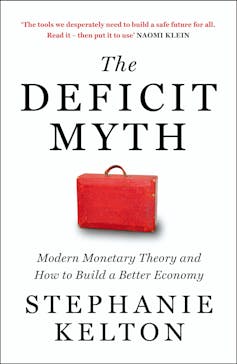

Stephanie Kelton, Hachette Australia

No book prepared ahead of time better targeted the year in economics.

Just as governments including Australia’s were embracing debt (A$800 billion and counting) and creating money out of nowhere ($200 billion scheduled) came a treatise explaining that at times like these (actually, at any time when the resources of the economy aren’t fully employed) that’s entirely responsible.

Stephanie Kelton’s book has rightly been displayed on Alan Kohler’s desk, and Kohler himself has become a convert to modern monetary theory which the book outlines in the clearest of terms.

Kelton explains that in an economy such as Australia’s the purpose of tax isn’t to raise money but to slow spending, and something else: demanding the payment of tax in Australian dollars forces Australians to use Australian dollars.

The example of teenagers not cleaning up around the house that she used in her talk at Adelaide University in January is priceless. You can watch the video here.

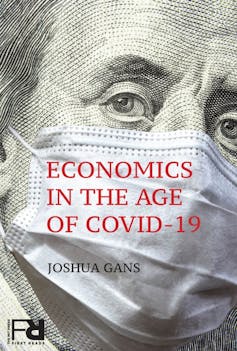

Joshua Gans, MIT Press

Written as we were coming to grips with what to do, and posted online chapter by chapter to get real-time feedback, the Australian author’s flash of inspiration was that we have experience in shutting down an economy and then restarting it.

We do it every Christmas writes Joshua Gans, and “no-one screams depression”.

That his way of seeing things now dominates talk about the pandemic doesn’t make it less radical. It’s partly because of his insights, published in April, that most governments no longer think that in this crisis they can trade off health against wealth.

He persuades by analogy. Fans of Mission Impossible II, the computer game Plague Inc and the came of chess will appreciate the references.

Mervyn King, John Kay, Hachette Australia

The idea that every possibility can be reduced to a number, to a probability, is what makes simple mathematical economics work. It’s what makes insurance and credit ratings and assessments of the risk of getting coronavirus work. And it is wrong, as became clear in the devastation caused by the global financial crisis.

By itself, that’s not a particularly useful observation, but what is useful is the author’s discovery of where the idea that probability could be reduced to a simple number came from. The Nobel Prize winning economist Milton Friedman shares much of the blame. He insisted that every uncertainty could be reduced a number that a rational utility-maximising human being could use to make decisions.

Before Friedman and contemporaries, there used to be two numbers, one representing risk, and the other representing uncertainty, which are quite different things and can’t be thrown together.

If you’re too busy for the book, try the London School of Economics podcast.

Dietrich Vollrath, University of Chicago Press

Advanced economies may or may not roar out of the recession, but they are unlikely to boom as they did before. For decade after decade throughout the 1900s annual economic growth has been strong, averaging 2% per capita in the US.

In the first two decades of the 2000’s that growth has been weak, averaging 1% – only half of what it did.

Dietrich Vollrath, who blogs on growth and had no preconceptions, approached the puzzle as a mystery and found that the usual suspects (rising inequality, slower innovation, competition from China) didn’t explain enough.

The extra comes from success. The populations of the US and kindred nations have become so rich and (on average) old that having more children and striving for even higher incomes no longer makes sense.

The technical stuff is at the back. The message from the front is that we’ve arrived at our destination, which needn’t be a bad thing.

John Quiggin, Princeton University Press

I’ve slipped this one in from 2019 for a reason. John Quiggin is about to publish a sequel, The Economic Consequences of the Pandemic.

Economics in One Lesson, published in 1946 financial journalist Henry Hazlitt, was a homage to the power of prices in a free market.

In lesson one (the first half of the book) Quiggin teases out Hazlitt’s thinking, and in lesson two shows how it follows from it that in many circumstances the market has to be contained.

Central to both lessons is opportunity cost, “what you give up in order to get something”, the most important concept in economics.

Polluters will make the wrong decisions if the cost of their pollution (largely borne by others) isn’t charged for. It’s a persuasive and increasingly-pressing argument.![]()

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Jessica Gildersleeve, University of Southern Queensland

Summer is the time for holidays and travel. But as we weakly wave goodbye (we hope) to the horrors of 2020, international travel is off the table and even domestic travel is still restricted.

A book is still your most faithful companion on summer journeys, even if that trip is limited to the journey between the kitchen and a sun lounge in the backyard.

Curated here is a mix tape of great literary road trips. There is one oldie but goodie, some 21st-century hits and shout-outs to the authors who mapped the way. Buckle up — or curl up — and enjoy.

Read more:

Friday essay: Alice Pung — how reading changed my life

Our journey begins with The Canterbury Tales, one of literature’s earliest road trip narratives, although Chaucer’s work takes its lead from Giovanni Bocaccio’s Decameron (c. 1353).

A series of stories told by a group of travellers, in Chaucer’s Middle English, takes readers on a pilgrimage to the shrine of Saint Thomas à Becket in Canterbury. Indeed, the pilgrimage can be seen as the earliest form of today’s holiday (a “holy day”), in which the faithful would journey for days or even weeks to visit a holy site. The physical demands of the travel itself contributed to the pilgrim’s spiritual growth.

Each pilgrim of The Canterbury Tales represents a different class or social position — the knight, the priest, the merchant, and so on. Additionally, each story not only represents a particular and symbolic genre — the low humour of the miller’s fabliaux, or the knight’s idealisation of the courtly love poem — but when taken together signify the interactions between people and experiences of the period.

Read more:

Chaucer’s great poem Troilus and Criseyde: perfect reading while under siege from a virus

If you enjoy The Canterbury Tales, you might also like Homer’s epic poem The Odyssey (8th C BCE) — a heroic adventure on the high seas. Likewise: Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea and Around the World in Eighty Days (both first published in English in 1872), or Jonathan Swift’s satirical masterpiece, Gulliver’s Travels (1726).

Perhaps best known for the image of Reese Witherspoon tossing her hiking boots into a canyon in the 2014 film adaptation, Cheryl Strayed’s memoir of her solo hike along the Pacific Crest Trail is an epic pilgrimage in its own right.

Just as the archetypes of The Canterbury Tales undertake both a physical and a spiritual journey, so too Strayed commits to the trail as a trip of transformation and discovery: “a world I thought would both make me into the woman I knew I could become and turn me back into the girl I’d once been. A world that measured two feet wide and 2,663 miles long”.

Wild constitutes a modern, even feminist, reimagining of the American frontier narrative — a lone journey into the “wild west”, stripped of the markers of civilisation to truly find a self-made paradise. The book echoes and subverts the classic road trip novel, Jack Kerouac’s On the Road (1957) — a compulsory addition to any literary road trip list. It also hearkens back to Mark Twain’s boyhood novel, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1885), or even Vladimir Nabokov’s twisted trip in Lolita (1955).

Read more:

Mythbusting Ancient Rome — did all roads actually lead there?

That the road trip is frequently used as a symbolic journey of understanding the self makes it ripe for the contemporary bildungsroman form — a novel of development — in the Young Adult genre. Author John Green has plumbed this trope a number of times, perhaps most successfully in Paper Towns. The acclaimed Amy & Roger’s Epic Detour by Morgan Matson (2010), or the more recent I Wanna Be Where You Are by Kristina Forest (2019) both also fall within this category.

Poised on the precarious cusp of adulthood and searching for their adventurous friend Margot, the teenaged protagonists of Paper Towns set off on a road trip through the night, determined to “right a lot of wrongs … wrong some rights … (and) radically reshape the world”. It is thus a moral journey, an effort to imprint the emerging self on a world not yet acknowledging its presence. The travellers want to make decisions about their lives, rather than be swept down a predetermined road.

Read more:

The kids are alright: young adult post-disaster novels can teach us about trauma and survival

Australian road trip narratives are more often described by fear than frontierism, as in Kenneth Cook’s Wake in Fright (1961) or cinema’s Wolf Creek (2005). Similarly, Ari’s drug-fuelled trip around inner Melbourne in Christos Tsiolkas’s Loaded (1995) tracks the urban intersections of individual, national and multicultural identity.

2020 has been a triumphant year for Tara June Winch. Her earlier short story cycle, Swallow the Air won the David Unaipon Award.

With a nod to the structure of The Canterbury Tales, Winch’s stories follow the cross country journey of a young Indigenous girl, May. She is determined to escape and change the cycles of violence and misery to which her family has been subjected. Like Tony Birch’s Blood (2012), it adopts the road trip as a means of going back to Country, providing not only a specifically cultural innovation in the genre, but a different understanding of self-discovery.

Read more:

The Yield wins the Miles Franklin: a powerful story of violence and forms of resistance

Not all road trips constitute journeys into the self. Instead, a psychological voyage might constitute a plunge into the depths of the nightmarish unconscious.

Joe Hill, son of that most famous horror writer Stephen King, offers up a road trip we might prefer not to take, although it does have a festive theme. In N0S4A2, Christmasland is the horrific and fantastic destination for the child victims of a phantom vehicle and its deranged driver.

Hill offers the chilling prophesy that “sooner or later a black car came for everyone”, pointing out the horrific inevitability of one final road trip. It’s a journey in the tradition of the monstrous vehicle, as in King’s Christine (1983), as well as the apocalyptic father-son walk in Cormac McCarthy’s The Road (2006), Josh Malerman’s Bird Box (2014), King’s The Stand (1978) and (as Richard Bachman) The Long Walk (1979).

After the year we’ve all had, I hope your road trip is less nightmarish.![]()

Jessica Gildersleeve, Associate Professor of English Literature, University of Southern Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Eamonn O’Neill, Edinburgh Napier University

Earlier this year, as the world came to terms with the coronavirus pandemic, a letter purporting to have been written by F Scott Fitzgerald in the midst of the 1918 flu pandemic did the rounds on the internet. It was, of course, a parody, but the writing style and notes to his pal Ernest Hemingway meant the letter – unless you’re a Fitzgerald expert – was pretty convincing:

At this time, it seems very poignant to avoid all public spaces. Even the bars, as I told Hemingway, but to that he punched me in the stomach, to which I asked if he had washed his hands. He hadn’t. He is much the denier, that one. Why, he considers the virus to be just influenza. I’m curious of his sources.

Its real author, Nick Farriella, had expertly muddied the tone of Fitzgerald’s language with, some contemporary 21st century concerns, and a dash of the clichéd image of the character we’ve come to know as “Hemingway” – something of a macho bore, brawler and liar.

It’s an unfortunate, but sometimes well-deserved, persona, as I have come to know intimately whilst doing research for a new book examining his often ignored, shadowy time spent in London and Europe before and after D-Day.

This was an arguably defining time in his life and career, when he was possibly the best known living writer in the world and something of a one-man global commercial brand. Even then, I have discovered that when he was in the company of undercover spies and well-known authors (sometimes, like his friend Roald Dahl) he could be, by turns, thoughtful, loving, brilliant, brave, embarrassing, abusive and downright nasty.

For some, the tone of the parody pandemic letter was a brief moment of entertainment because it was the return of the cartoonish wild-eyed and comical version of Hemingway from Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris. For others, who knew a little more about Hemingway, it was yet another simplistic attempt to besmirch his deeply complex legacy – fake news, you might say.

In fact, Hemingway’s response to the pandemic of 1918-19 – and later waves too – was very different from the parody. The truth is effortlessly stranger and more enigmatic than any fiction. Of course Hemingway was guilty of hyping facts to meet his mantra that fiction could be truer than the truth. But that didn’t change his basic respect for scientific facts and the natural world.

He was, after all, the dutiful son of a doctor from Oak Park, Illinois who’d witnessed first-hand his father’s work and used the experiences in his later fictional works. The Hemingway scholar Susan Beegel has shown how serious illness, disease, sudden and prolonged death were nothing new to him. He was aware, in humans and animals, of the fragility of life.

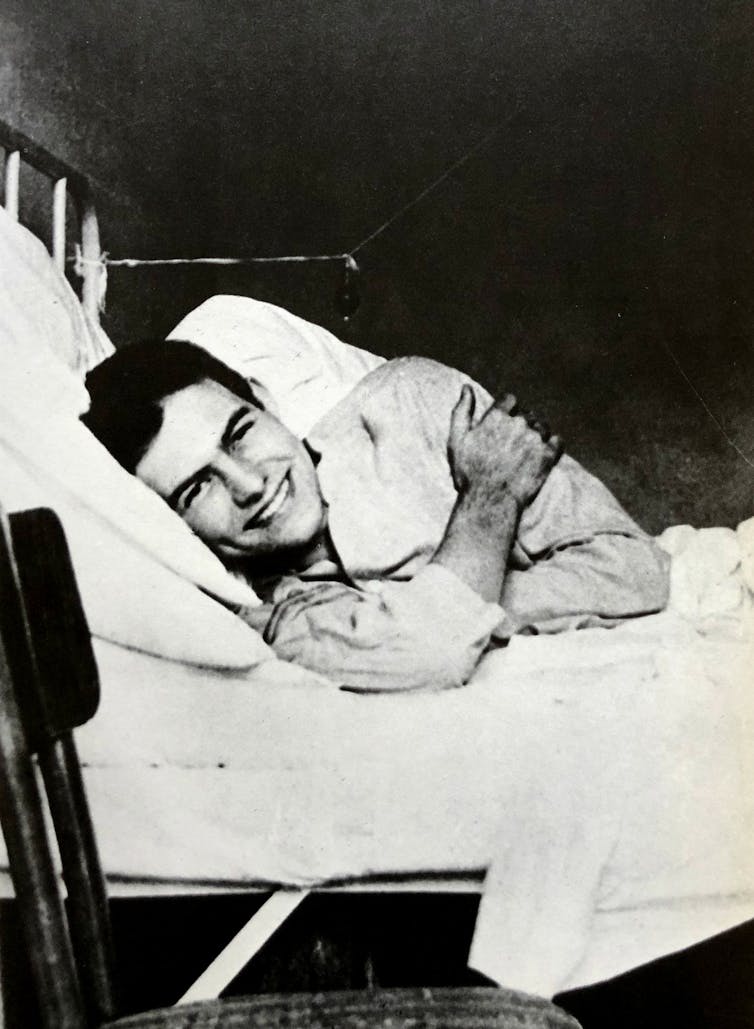

The GP’s son later had his own appalling experiences in the first world war, when he volunteered for the Red Cross. Bad eyesight meant normal duty was out of the question, but a determined Hemingway used the Red Cross to get to the Italian front line instead.

Within hours of arriving in Italy, Hemingway was tasked with cleaning up the body parts of victims of shelling, a sight he recounted in his controversial short work “A Natural History of the Dead”, that both fascinated and horrified him. Within weeks he would be pulled off a battlefield himself, a bloodied wreck more dead than alive, with 228 pieces of shrapnel embedded in his legs. Long days and painful nights of touch-and-go recuperation followed.

Yet later, after shadowing Red Cross nurses, Hemingway wrote about the worst death he ever saw. It hadn’t been from a bomb or a bullet: “The only natural death I’ve ever seen […] was death from the Spanish influenza. In this you drown in mucus, choking, and how you know the patient is dead is; at the end he shits the bed.”

This horrendous scene was common amidst a global pandemic which had claimed, by December 1919, 50 million people. There was no coordinated national and international research as we would know it, no effective treatment, and certainly no vaccine on the way. Soldiers and volunteers like Hemingway were literally swimming in the virus.

Yet Hemingway dodged the peaks of the 1918-19 pandemic waves by weeks, sometimes days, as he convalesced in Italy, and then returned to the US. Once home, he discovered family and friends had perished from it. Despite youthful public insouciance, all these experiences privately scarred him, and that dying soldier in Italy was never far from his mind.

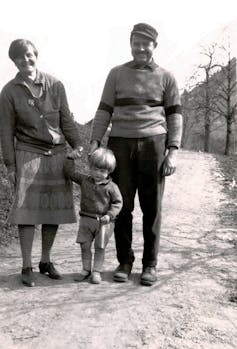

According to as his masterful biographer Michael Reynolds, Hemingway’s superstition about death meant that “the slightest possibility of flu often sent him scurrying for healthier conditions, for he had a particular horror of drowning in his own fluids”. Consequently, by 1926 and now living in Paris, when his son Jack, nicknamed “Bumby”, developed a “hacking cough”, Hemingway immediately sent him and his wife Hadley off to the clean air and sunshine of the Riviera to recover, while he went solo to Spain to work.

Hadley and Bumby Hemingway arrived at Antibes on May 26 1926, and the child was immediately diagnosed with the infectious – and potentially fatal – whooping cough. Quarantine was called for, so both were summarily housed by their hosts, the ever-generous patrons of the arts Sara and Gerald Murphy, in a small dwelling near their own 14-roomed Villa America.

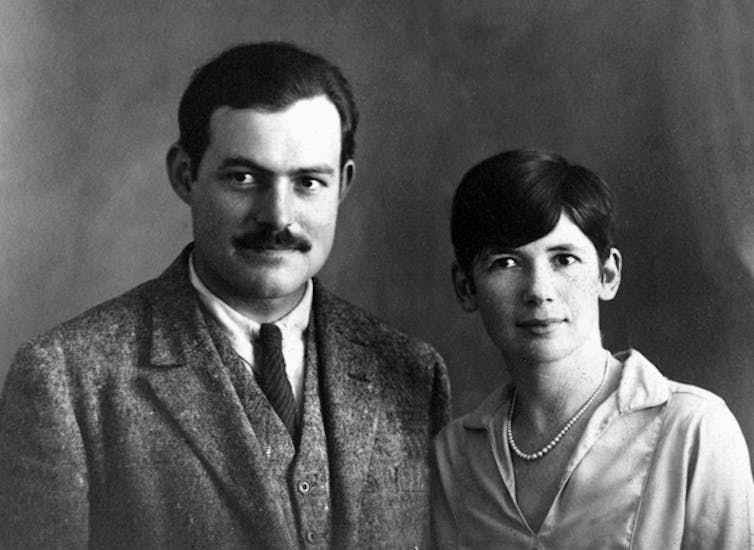

One week later they were moved again, under quarantine conditions, to a hastily vacated Villa Paquita at Juan les Pins, previously inhabited by Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, who had zipped off to the safety of another coastal retreat. To complicate matters, Hemingway’s mistress Pauline Pfeiffer, a chic Paris-based editor at Vogue magazine, arrived from Paris, and within 48 hours, they were joined fresh from Madrid by the central figure in this peculiar set-up, Hemingway himself.

For a while, quarantining was all very jolly. By day, Hemingway dedicated himself to editing corrections to his soon-to-be bestseller The Sun Also Rises. By evening, everyone gathered for socially-distanced cocktails with the Murphys and Fitzgeralds, who stayed outside the garden fence. Empty bottles, drained and upended, were mounted like heads on the spiked fence. Each one marked another day of quarantine for the Hemingway child.

It worked – to an extent.

Quarantine ended when his son got better, though as a precaution he and his nanny were housed nearby, leaving Hemingway in a nice hotel with the two women. He pretended he was happy but inevitably, the post-lockdown arrangement slid into emotional anarchy. Hadley Hemingway and he argued, while Pfeiffer hung on for the prize she wanted most – Hemingway himself. It stayed that way as everyone decamped from the Riviera to Pamplona, Spain for the annual fiesta.

Within a year of that quarantined summer, the Hemingways were divorced.

In 1937, 11 years later, despite quarantining in Saranac Lake, Upstate New York, the Murphy’s 16-year-old son Patrick died from tuberculosis.

Hemingway rose at dawn on July 2 1961 in Idaho and took his own life.

The child who had the whooping cough in 1926, Jack “Bumby” Hemingway, had a happier outcome than most in his family. He became a decorated second world war veteran who survived capture and imprisonment after parachuting into Nazi Germany, and died peacefully in 2000.![]()

Eamonn O’Neill, Associate Professor in Journalism, Edinburgh Napier University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Rebecca Wray, Leeds Beckett University

On December 9, debate began to simmer on social media over the resemblance of two popular women’s empowerment books released in 2020: Chidera Eggerue’s How to Get Over a Boy (published in February by Quadrille Publishing) and Florence Given’s Women Don’t Owe You Pretty (published in July by Cassell Illustrated).

Comparisons between the two have circulated for some time. Given and Eggerue, also known as The Slumflower, are both influencers (people with large followings and marketing influence on social media) and both promote a message of self-love, acceptance, and body positivity.

Earlier this month, Eggerue and some of her followers accused Given of copying two of her books: How to Get Over a Boy and her debut, What a Time to be Alone. This sparked fresh questions over similarities between their works in terms of style and content.

Both of the women’s books are eye-catching, with vibrant covers, large text, and colourful illustrations throughout. Eggerue claims her books sparked a new wave of self-help literature “that had never been seen before”.

While at first glance it could appear as though we’re looking at a copycat case, we shouldn’t forget that publishers like trends and will try to cash in on what’s popular. The cover style of both Given and Eggerue’s books chime with design trends from 2019 from their plain large fonts to their use of colour and illustration. Searching for either book on platforms such as Google and Amazon often brings up the other, and the latter even bundles the two author’s books together.

Popular feminist books targeted at a mainstream audience are nothing new. Over the last 15 years there have been dozens of light, easy-to-read feminist texts, often with the aim of making feminism “fun”, “cool”, and even “sexy”. Laura Bates’ Girl Up (2016) in particular bears the most resemblance to these newer self-help books in the way it challenges sexist expectations through humour and quirky illustrations.

But there are countless examples: from Jessica Valenti’s Full Frontal Feminism (2007) to Holly Baxter and Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett’s The Vagenda (2015), books like Ellie Levenson’s The Noughtie Girl’s Guide to Feminism (2009), Caitlin Moran’s How to be a Woman (2011), or Polly Vernon’s Hot Feminist (2015). While these books can vary in approach and style, a number put forward similar messages – personal empowerment, self-love, and the right to choose.

Some of these books have been criticised for selling self-help as a solution to injustice, rather than working with others for political and social change. In academia, feminists argue that popular feminism is at best a diluted form of feminism that treats it simply as a form of self-help focused on “what’s right for me” – a brand which can be packaged and sold.

Read more:

Five books by women, about women, for everyone

What all these books have in common is their desire to make feminism accessible to their readers, which isn’t a bad thing in itself. It has long been argued that feminism has an “image problem”, and that it is no longer needed in the West. It has also has been declared unappealing and irrelevant to young women by newspapers and in polls run by OnePoll and the online community Netmums.

Academic feminist literature meanwhile has been criticised for tending to be theory-heavy and filled with impenetrable jargon. Matters are not helped by such texts being inaccessible to the general public, often being placed behind paywalls or published as costly hardbacks. This leaves a gap which popular feminism fills whether through blogs, social media posts, or affordable paperbacks.

However, this is where the world of marketing tends to step in to “save feminism” through rebranding exercises. It’s a process which often involves mainstream women’s magazines such as ELLE, Stylist, Grazia, or Cosmopolitan hiring advertising agencies to make feminism fashionable and challenge negative stereotypes of angry, ungirly feminists. As with popular feminism books, these attempts have varied in quality.

Since the 1990s, young feminists’ writing has been criticised for being focused on personal anecdotes at the expense of theory and now is no different. Popular feminism is often skewered by critics of being superficial, fluffy, apolitical, individualised, and consumer-driven.

Reading around the subject, you’ll find different labels used to describe this brand of feminism, including: “popular feminism”, “new feminism”, “young feminism”, “consumer feminism”, “choice feminism”, “neoliberal feminism”, and “mainstream feminism”. Whatever the label, the objection is the same: that feminist ideology is being commodified, de-fanged, and made attractive to a general audience.

Popular feminist books are often designed to appeal to younger readers, rather than those well versed in feminist theory. Eggerue makes it clear that she used an easy-to-read writing style because she didn’t want her book to intimidate readers.

These books all look and sound the same because they are meant to be starting platforms for those who are new and curious about sexism, inequality, and feminism. They click with younger readers and I’m sure there will be more to come aimed at future generations.

What’s more difficult though, is bridging the gap between these “starter” 101 books and more challenging, critical texts. While the former are more readily marketable and appealing to publishers, the latter still tends to occupy less visible spaces. This lack of visibility for other feminist texts means a rich wealth of ideas and thoughts are not being heard outside niche spaces like academia and activist circles.

On the flip side, feminist voices dominating mainstream spaces are selling women the idea that social and political inequalities can be simply overcome through self-will and self-improvement: “You go girl!”![]()

Rebecca Wray, Critical Psychologist and Specialist Mental Health Mentor, Leeds Beckett University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Richard Ovenden, University of Oxford

In 2006 I wrote a speculative letter to David Cornwell (better known by his nom de plume, John le Carré) containing a polite request that, if he hadn’t made other plans, would he consider donating his papers to the Bodleian Library at Oxford University.

The Bodleian holds important collections of archives and manuscripts (among many other things) of politicians, scientists, philosophers, and of course writers. I felt that his papers should be in a British institution – and where better than the research library of the university where he had been an undergraduate (he read modern languages at Oxford in the 1950s).

The reply came back very swiftly: he had not been asked by any other British institution, and had rebuffed offers from US libraries with deep pockets, adding, “I am delighted to be able to do this. Oxford was Smiley’s spiritual home, as it is mine. And while I have the greatest respect for American universities, the Bodleian is where I shall most happily rest.”

Now the great writer has died, I have been reflecting on the legacy of his archive and on the friendship that exchange initiated. David and his wife Jane came to visit a few weeks later and I followed this up the following spring with a visit to their Cornish home, near where my family and I often holidayed. David treated my family to a cliff-top game of croquet, while Jane and I went to survey the papers which were stored in a converted barn. They had been very carefully boxed, book-by-book, making our archival task considerably easier.

The first 85 boxes arrived in the Bodleian a little while later and we were able to begin the task of cataloguing the first tranches of papers, which has made it possible for students and scholars to access these materials, and for us to include them in exhibitions and seminars.

The papers are most revealing of David’s approach to writing, and of his collaboration with Jane. Take his classic Tinker Tailor, Soldier, Spy for example. The papers show how the novel evolved in the process of composition from its early working title – The Reluctant Autumn of George Smiley – to the final published text.

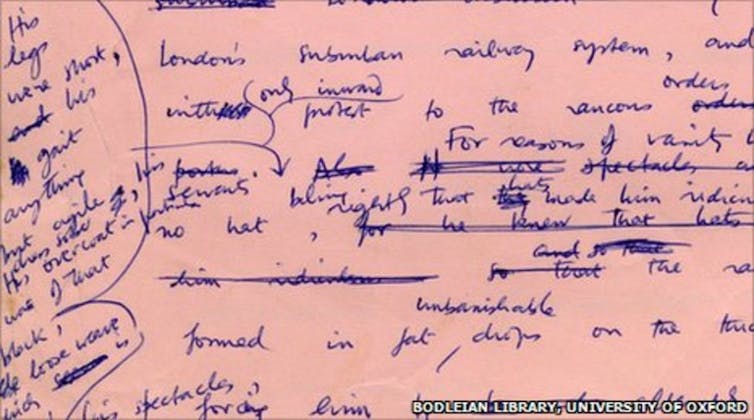

There are almost 30 drafts of the novel made during the process of composition, 1972-4, from the first hand-written manuscripts through to the final proofs. Each of these show an incredible intensity of close attention to the text: important changes are made on each version, the author determined to improve the work right up to the moment when it finally goes off to the printer.

The early drafts show a deep process of collaboration with his wife, Jane. He would hand the manuscript of the first draft over to her to be typed up, and the typescript would then be worked on: attacked with scissors and staple-gun, with more layers of manuscript additions and rewrites in every spare inch of white paper. The process would be repeated many times through the subsequent drafts, often creating a document that must have been incredibly hard for Jane to interpret and lay the newly revised text out cleanly and clearly on a new sheet of blank paper, but their close working made the process efficient and effective. Her participation in the creation of the novels, which was constructively editorial, has been too often overlooked.

One of the undated, untitled drafts is an early version of the beginning of chapter two, in which George Smiley is introduced to the reader as: “small, podgy … one of those gentle, reluctant worker-bees who throng London’s suburban railway system”. The bee metaphor was eventually excised from the published text, but in this draft many of Smiley’s familiar characteristics are already present and more are added as David amends and elaborates his first thoughts. A fuller picture of the spymaster begins to emerge: “His legs were short, his gait anything but agile, his dress sober”.

Two slightly later drafts (with the bee comparison retained) are titled The Reluctant Autumn of George Smiley, the second version with the subtitle “being the first story of THE QUEST FOR KARLA”. Only the latest drafts are titled Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy and begin with a description of Thursgood School, where one of the key characters in the plot has hidden away, rather than an introduction to Smiley.

The materiality of these drafts: the layers of manuscript over typescript, the stapled additions of cut-outs from other drafts and versions, all combine to show to me that David was not just an artist, but approached his writing as a craft as well. He put a great deal of time, energy and care into the process of composition – a process that was physical as well as intellectual.

I am often asked where I place the writers whose archives we have in “the western canon” – if you like, the “hall of literary fame”. Perhaps there is a sense that having your papers in the Bodleian is a form of “canonisation”, but the world of letters is moving away from the notion of the canon, and more embracing of allowing new voices to be heard from around the world, increasingly in languages other than English.

Now that le Carré will write no more, will his novels still be read in 50 years time? I am certain they will. His work is remarkable for sustaining the popular and critical acclaim throughout his literary lifetime, almost into his tenth decade. Students will find his work an increasingly fertile field for dissertations – and scholars are already approaching him as a narrator not just of the Cold War, but of post-war geopolitics.

Read more:

John Le Carré: authentic spy fiction that wrote the wrongs of post-war British intelligence

The real success of David Cornwell’s writing to me is that his books are not easy. They are brilliantly written, painstakingly constructed, and have superbly drawn characters and thrilling plot lines. But the texts are complex and require effort on the part of the reader to comprehend the intricacies and remember small details which are often critical to the plot.

It is in this complexity that le Carré conveys the reality of the world. Things are not simple when human beings are involved. Their contradictions and complexities are what make our world an intriguing, interesting, and infuriating place. David Cornwell, as John le Carré, described and conveyed it like no other writer.![]()

Richard Ovenden, Director of the Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The links below are to articles relating to news concerning Audible.

For more visit:

– https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/nov/26/audible-adjusts-terms-after-row-over-easy-exchanges-that-cut-royalties-amazon

– https://publishingperspectives.com/2020/11/international-authors-organizations-not-satisfied-with-audible-on-returns/

You must be logged in to post a comment.