Richard Ovenden, University of Oxford

In 2006 I wrote a speculative letter to David Cornwell (better known by his nom de plume, John le Carré) containing a polite request that, if he hadn’t made other plans, would he consider donating his papers to the Bodleian Library at Oxford University.

The Bodleian holds important collections of archives and manuscripts (among many other things) of politicians, scientists, philosophers, and of course writers. I felt that his papers should be in a British institution – and where better than the research library of the university where he had been an undergraduate (he read modern languages at Oxford in the 1950s).

The reply came back very swiftly: he had not been asked by any other British institution, and had rebuffed offers from US libraries with deep pockets, adding, “I am delighted to be able to do this. Oxford was Smiley’s spiritual home, as it is mine. And while I have the greatest respect for American universities, the Bodleian is where I shall most happily rest.”

Now the great writer has died, I have been reflecting on the legacy of his archive and on the friendship that exchange initiated. David and his wife Jane came to visit a few weeks later and I followed this up the following spring with a visit to their Cornish home, near where my family and I often holidayed. David treated my family to a cliff-top game of croquet, while Jane and I went to survey the papers which were stored in a converted barn. They had been very carefully boxed, book-by-book, making our archival task considerably easier.

The first 85 boxes arrived in the Bodleian a little while later and we were able to begin the task of cataloguing the first tranches of papers, which has made it possible for students and scholars to access these materials, and for us to include them in exhibitions and seminars.

Evolution of an idea

The papers are most revealing of David’s approach to writing, and of his collaboration with Jane. Take his classic Tinker Tailor, Soldier, Spy for example. The papers show how the novel evolved in the process of composition from its early working title – The Reluctant Autumn of George Smiley – to the final published text.

Bodleian Library, University of Oxford

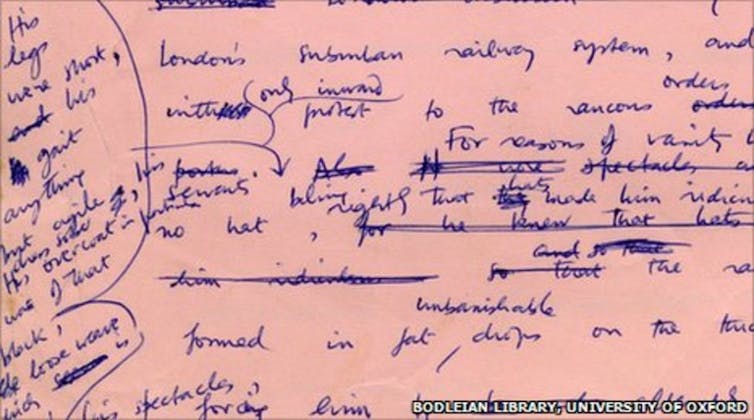

There are almost 30 drafts of the novel made during the process of composition, 1972-4, from the first hand-written manuscripts through to the final proofs. Each of these show an incredible intensity of close attention to the text: important changes are made on each version, the author determined to improve the work right up to the moment when it finally goes off to the printer.

The early drafts show a deep process of collaboration with his wife, Jane. He would hand the manuscript of the first draft over to her to be typed up, and the typescript would then be worked on: attacked with scissors and staple-gun, with more layers of manuscript additions and rewrites in every spare inch of white paper. The process would be repeated many times through the subsequent drafts, often creating a document that must have been incredibly hard for Jane to interpret and lay the newly revised text out cleanly and clearly on a new sheet of blank paper, but their close working made the process efficient and effective. Her participation in the creation of the novels, which was constructively editorial, has been too often overlooked.

One of the undated, untitled drafts is an early version of the beginning of chapter two, in which George Smiley is introduced to the reader as: “small, podgy … one of those gentle, reluctant worker-bees who throng London’s suburban railway system”. The bee metaphor was eventually excised from the published text, but in this draft many of Smiley’s familiar characteristics are already present and more are added as David amends and elaborates his first thoughts. A fuller picture of the spymaster begins to emerge: “His legs were short, his gait anything but agile, his dress sober”.

Two slightly later drafts (with the bee comparison retained) are titled The Reluctant Autumn of George Smiley, the second version with the subtitle “being the first story of THE QUEST FOR KARLA”. Only the latest drafts are titled Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy and begin with a description of Thursgood School, where one of the key characters in the plot has hidden away, rather than an introduction to Smiley.

The materiality of these drafts: the layers of manuscript over typescript, the stapled additions of cut-outs from other drafts and versions, all combine to show to me that David was not just an artist, but approached his writing as a craft as well. He put a great deal of time, energy and care into the process of composition – a process that was physical as well as intellectual.

A place in the pantheon

I am often asked where I place the writers whose archives we have in “the western canon” – if you like, the “hall of literary fame”. Perhaps there is a sense that having your papers in the Bodleian is a form of “canonisation”, but the world of letters is moving away from the notion of the canon, and more embracing of allowing new voices to be heard from around the world, increasingly in languages other than English.

Now that le Carré will write no more, will his novels still be read in 50 years time? I am certain they will. His work is remarkable for sustaining the popular and critical acclaim throughout his literary lifetime, almost into his tenth decade. Students will find his work an increasingly fertile field for dissertations – and scholars are already approaching him as a narrator not just of the Cold War, but of post-war geopolitics.

Read more:

John Le Carré: authentic spy fiction that wrote the wrongs of post-war British intelligence

The real success of David Cornwell’s writing to me is that his books are not easy. They are brilliantly written, painstakingly constructed, and have superbly drawn characters and thrilling plot lines. But the texts are complex and require effort on the part of the reader to comprehend the intricacies and remember small details which are often critical to the plot.

It is in this complexity that le Carré conveys the reality of the world. Things are not simple when human beings are involved. Their contradictions and complexities are what make our world an intriguing, interesting, and infuriating place. David Cornwell, as John le Carré, described and conveyed it like no other writer.![]()

Richard Ovenden, Director of the Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.