THE CANADIAN PRESS/Justin Tang

Mary Chapman, University of British Columbia

In March, when a white man targeted and killed eight women in Atlanta, six of whom were Asian, mainstream media and police initially refused to categorize it as a racially motivated hate crime. But for Asian people, across North America and globally, this tragedy was one more episode in a long history of anti-Asian violence.

Over 150 years ago, white settlers in the United States rounded up Chinese merchants and miners and put them onto burning barges, threw them into railway cars and even lynched them. But this story is not limited to the U.S. — early Chinese immigrants were not welcome in Canada either.

Read more:

Asian Americans top target for threats and harassment during pandemic

This is documented in the life and works of Chinese-Canadian author and journalist Edith Eaton (1865-1914). While researching Becoming Sui Sin Far: Early Fiction, Journalism, and Travel Writing by Edith Maude Eaton, I discovered numerous accounts of early Canadian anti-Chinese racism in her work.

Memoirs from the past show similar hatred

In Eaton’s memoir Leaves from the Mental Portfolio of an Eurasian, she recalls being called “Chinky, Chinky, Chinaman, yellow-face, pig-tail, rat-eater,” after moving to North America with her family — a white father, Chinese mother and five siblings — in 1872.

Soon after the family’s arrival in Montréal, locals would call out “Chinese!” “Chinoise!” as they walked down the street. Classmates would pull Eaton’s hair, pinch her and refuse to sit beside her.

These taunts and torments were felt deeply by Eaton throughout her life. She wrote:

“I have come from a race on my mother’s side which is said to be the most stolid and insensible to feeling of all races. Yet I look back over the years and see myself so keenly alive to every shade of sorrow and suffering that it is almost a pain to live.”

Eaton published a book of short stories depicting Chinese immigrants’ encounters with racism under the pseudonym “Sui Sin Far” (Cantonese for narcissus). And her advocacy was appreciated by Chinese people in Montréal who erected a memorial beside her grave with the inscription “Yi bu wang hua,” which means “The righteous one does not forget China.”

Since the Atlanta shootings, Asian women have been assaulted and even killed. Asian people have been accused of causing COVID-19, stealing intellectual property and more. What Eaton described in her fiction and memoir continues to happen today.

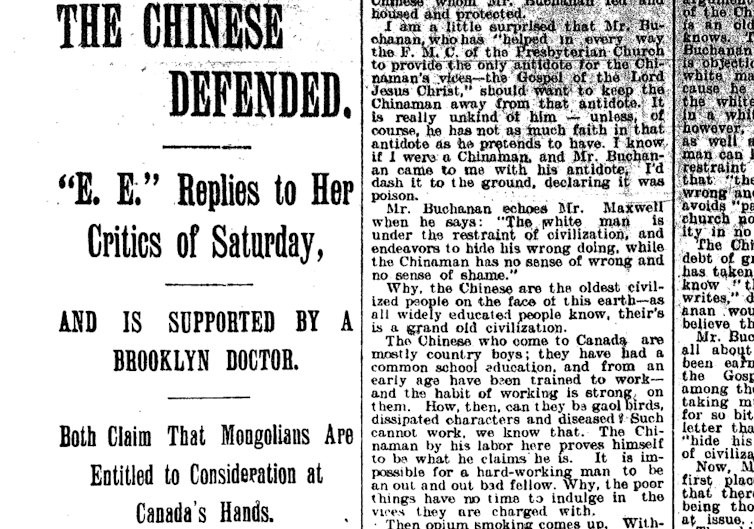

Montréal Daily Star

1890s headlines interchangeable with today’s

Eaton also documented anti-Chinese violence and championed the rights of Chinese immigrants in stories published in the Montréal Star and the Montréal Witness throughout the 1890s.

At the time, white men were convinced that Chinese immigrants were taking their jobs away and that Chinese men — many of whom lived alone behind their shops (because of the Head Tax — had an unfair advantage over white men with families.

In the Montréal Star, Eaton published A Plea for the Chinaman, in which she called out politicians for mistreating Chinese men in Canada:

“Every just person must feel his or her sense of justice outraged by the attacks which are being made by public men upon the Chinese who come to this country.… It makes one’s cheeks burn to read about men of high office standing up and abusing a lot of poor foreigners behind their backs and calling them all the bad names their tongues can utter.”

Anti-Chinese violence was so common in 1890s Montréal that Chinese men carried police whistles in their pockets. In an 1895 article, titled Beaten to Death, Eaton noted that even when they blew their whistles, no one would come to Chinese men’s aid. Bystanders often refused to identify their assailants and police told the men who had been assaulted that they should be arrested for bothering them.

The recent reports of a security guard’s refusal to act when a Filipino woman was brutally beaten uncannily recall the anti-Asian violence Eaton documented 125 years ago.

My research leads me to suspect that Eaton published other unsigned articles documenting anti-Chinese racism in Montreal newspapers at this time. She may have written a Gazette article reporting on youth who would gather nightly in Montreal’s Chinatown to throw stones at passing Chinese men and through the plate glass windows of their businesses, or those describing Chinese men being punched, kicked or beaten to death.

What was written when?

Looking at literature and journalism of the past such as Eaton’s can help illuminate the challenges of today. Her observations about people’s motivations — ignorance, jealousy, suspicion, competition — invite us to reflect on the motivations of today’s perpetrators of anti-Asian violence and conclude that not much has changed.

The anti-Asian racism recorded in Eaton’s work and journalism across Montreal persists today. Recent reports of racist violence, hate crimes, verbal harassment, opaque policing and passive bystanders could have been written more than a century ago.

We have a long way to go and a lot of work to do to make up for over a century of treating Asian people like they do not belong.![]()

Mary Chapman, Professor of English and Academic Director of the Public Humanities Hub, University of British Columbia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.