The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company by William Dalrymple

The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company by William Dalrymple

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

Community Reading Programs

The link below is to an article that takes a look at the benefits of community reading programs.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/benefits-of-community-reading-programs/

Google to Convert Ebooks to Audiobooks

The link below is to an article looking at how Google is going to convert ebooks to audiobooks.

For more visit:

https://goodereader.com/blog/audiobooks/google-is-going-to-convert-ebooks-to-audiobooks

More Advertisements on the Kindle Home Screen

The link below is to an article reporting on Amazon adding more advertisements to the Kindle Home Screen.

For more visit:

https://goodereader.com/blog/kindle/amazon-adds-more-advertisements-to-the-kindle-home-screen

2020 Albertine Prize Winner

The links below are to articles reporting on the 2020 winner of the Albertine Prize, Zahia Rahmani for ‘Muslim – A Novel.’

For more visit:

– https://lithub.com/zahia-rahmanis-muslim-a-novel-has-won-the-2020-albertine-prize/

– https://publishingperspectives.com/2020/12/2020-albertine-prize-zahia-rahamanis-muslim-in-matt-reecks-translation-covid19/

Cat in a spat: scrapping Dr Seuss books is not cancel culture

Kate Cantrell, University of Southern Queensland and Sharon Bickle, University of Southern Queensland

Let’s start by putting aside the bugbear that it is even possible to “cancel” children’s author Dr Seuss.

As Philip Bump wrote yesterday in The Washington Post,

No one is ‘cancelling’ Dr Seuss. The author, himself, is dead for one thing, which is about as cancelled as a person can get.

Laying aside a multimillion-dollar publishing business, tattered copies of Dr Seuss books clutter children’s bedrooms around the globe. Parents still grapple nightly with the tongue-twisters of Fox in Socks, Horton Hears a Who! or Hop on Pop, and try their best to keep their eyes open through a 20th reading of Green Eggs and Ham.

However, on Tuesday (what would have been Dr Seuss’s 117th birthday), the company that protects the late author’s legacy announced its plan to halt publishing and licensing six (out of more than 60) Dr Seuss books.

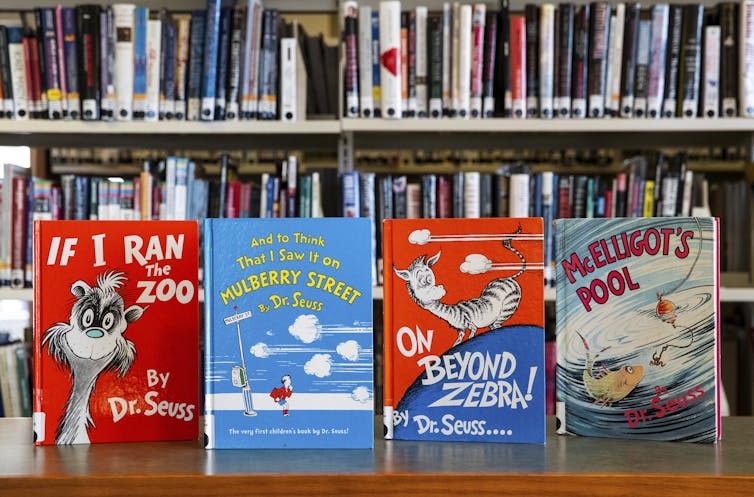

Few would know some of the discontinued titles, like McElligot’s Pool and The Cat’s Quizzer. However, many will recognise If I Ran the Zoo and And to Think That I Saw it on Mulberry Street, which have been criticised for racist caricatures and themes of cultural dominance and dehumanisation.

In If I Ran the Zoo, young Gerald McGrew builds a “Bad-Animal Catching Machine” to capture a turbaned Arab for his exhibit of “unusual beasts”.

“People will stare,” Gerald marvels, “And they’ll say, ‘What a sight!’”. Chinese “helpers” with “eyes at a slant” hunt exotic creatures in the mountains of Zomba-ma-Tant.

A reading recorded for Dr Seuss Day in 2019, removes the racist taunt. Instead of helpers who “wear their eyes at a slant”, the helpers “all wear such very cool pants”.

Nevertheless, pervasive racial imagery and subservient typecasting remain. That doesn’t mean Dr Seuss books should — or can — be scrapped altogether. Instead, these books present an opportunity to build awareness and teach young readers about history and context.

AP Photo/Steven Senne, File

Read more:

In Dr Seuss’ children’s books, a commitment to social justice that remains relevant today

Censorship in children’s titles

Children’s books are among those most often banned or censored. In this case, removing the Dr Seuss titles recognises that he was writing in a time and place when racial stereotyping was commonplace and frequently the focus of humour.

Elsewhere, controversy over golliwogs as racist caricatures was confrontingly played out in Enid Blyton’s Noddy stories. In her original telling of In the Dark, Dark Wood, Noddy is carjacked by three golliwogs who trap him, strip him naked, and leave him crying. “You bad, wicked golliwogs!” Noddy says. “How dare you steal my things!”

Similarly, in the first edition of Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, the Oompa-Loompas are African pygmies who have been “rescued” by Willy Wonka and enslaved in his factory. When Charlie says, “But there must be people working there,” Grandpa Joe responds, “Not people, Charlie. Not ordinary people, anyway.”

Read more:

Abused, neglected, abandoned — did Roald Dahl hate children as much as the witches did?

In his political cartoons, which appeared in a New York newspaper in the early 1940s, Dr Seuss ran the gamut of racist depictions, from African-American people as monkeys to Japanese characters with yellow faces and “rice paddy” hats.

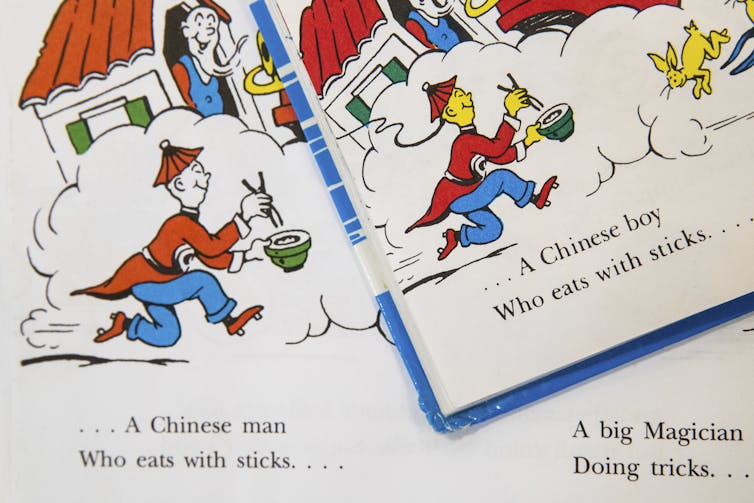

In the now-suspended The Cat’s Quizzer, there is “a Japanese” depicted in conical hat and stereotypical dress. On Mulberry Street, a Chinese man with bright yellow skin wears geta shoes and carries a bowl of rice.

In early editions, the caption underneath reads “A Chinaman who eats with sticks”. In 1978, over 40 years after the book was first published, the character’s skin tone and braid were changed. The caption was changed from “Chinaman” to “Chinese man”.

Christopher Dolan/The Times-Tribune via AP

If I ran the library … by today’s standards

Dr Seuss’s work contains racism and xenophobia, but should we judge him by today’s standards?

Children’s literature has always been subject to socio-historical shifts. It is a product of its time and the context in which it is created. Viewed through the changing lens of history, childhood itself is an unstable concept.

In other words, it is impossible to separate children’s literature from the ideological structure of our world, and from the particular historical moment in which it is produced.

While Dr Seuss’s best-loved characters — the Cat in the Hat, Horton the elephant, the Grinch — have earned their place in the canon, what we should be concerned about is the question of diversity in children’s literature.

We know from numerous studies that white children dominate children’s books, with talking animals and trains outnumbering the representations of First Nations, Asian, African and other minority groups.

Read more:

Empathy starts early: 5 Australian picture books that celebrate diversity

No quick fixes

Although never perfect, other beloved children’s literature series have sought solutions to similar dilemmas.

Enid Blyton’s stories have been continuously revised since the 1990s. Noddy is now carjacked by goblins, and, in the Faraway Tree series, Dame Snap replaces Dame Slap, with Fanny and Dick getting a makeover as Frannie and Rick.

More recently, Richard Scarry’s books were updated to depict Daddies cooking and Mummies going to work, while the latest film adaptation of The Witches cast actor of colour Jahzir Bruno as the boy protagonist.

Not surprisingly, queer representation in young adult fiction is still problematic, with most queer stories authored by writers who do not identify as queer.

On one level, the decision to discontinue half a dozen Dr Seuss books because “they are hurtful and wrong” seems a simple gesture (and one with relatively small financial impact). Racism permeates the Dr Seuss catalogue, including The Cat in the Hat’s origins in blackface minstrel performances. Like Dr Seuss’s Yertle, it’s turtles all the way down.

Instead, finding meaningful ways to contextualise these historical aspects for young readers today might be a better focus, rather than withholding a few and letting more prominent titles slide by.

Kids and teens, like adults, need to see themselves in the books they read, and young white readers need to see other cultural groups as something more than illegal, or violent, or criminal.

As chidren’s literature expert Perry Nodelman notes: “Stories structure us as beings in the world”. In the same week a Lowy study found one in five Chinese Australians have been threatened or attacked, it could not be more important to invest in an inclusive future for our kids.

Stephen Colbert’s segment finishes with suggested books by authors of colour.

![]()

Kate Cantrell, Lecturer in Writing, Editing, and Publishing, University of Southern Queensland and Sharon Bickle, Lecturer in English Literature, QLD rep for Australian Women’s and Gender Studies Association, University of Southern Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Youse wouldn’t believe it: a new book charts the 11-year making of a ‘people’s dictionary’ for Australia

shutterstock

Roslyn Petelin, The University of Queensland

Review: More Than Words: The Making of the Macquarie Dictionary by Pat Manser (Pan Macmillan)

In 1973 Pat Manser answered an advertisement in the Sydney Morning Herald seeking a research assistant to work on phonetic transcriptions for a dictionary of Australian English.

Now, nearly 50 years later, she has published her monumental account of the making of this dictionary, which in the words of Thomas Keneally, “paid the Antipodean tongue the great compliment of taking it seriously”.

If you’re a word aficionado, you’ll love this book. I could not put it down until I had read through to the end of the final section, which contains the wonderful launch presentation speeches for all eight editions of the Macquarie Dictionary.

Read more:

Gogglebox and what it tells us about English in Australia

The beginnings

John Bernard, a chemist who was appointed Associate Professor in the Department of English and Linguistics at Macquarie University in 1966, had published a paper in Southerly in June 1962 about the need for a dictionary of Australian English. He argued that we need

a dictionary of our own because our idiom, usage, invention and especially pronunciation are sufficiently different from those of other Englishes.

In December 1969, Brian Clouston, who had founded Jacaranda Press in Brisbane, agreed to fund a dictionary that would be

aggressively Australian, not to be encyclopedic, not to be illustrated, to be in one volume, and to be ready in two years.

Bernard’s colleague at the university, Professor Arthur Delbridge, was appointed chair of the editorial committee to compile the book. He argued for a “people’s dictionary” that would “hold up a mirror directly to contemporary Australian speech and writing”.

The critical decision at the outset was whether to describe how people use the language or prescribe how people should use the language.

shutterstock

The father of English lexicography, Samuel Johnson, whose prescriptivist A Dictionary of the English Language was published in 1755, felt “the duty of the lexicographer was to correct or proscribe”. The Oxford English Dictionary, published in 1928, had also been prescriptive.

However, the Macquarie editorial committee was “adamant that its dictionary was to be descriptive”, a move now standard in English language dictionaries. The committee wanted as comprehensive a dictionary as possible, so spoken as well as written words were included.

Johnson’s dictionary took seven years to compile. The Oxford dictionary took 70 years. Rather than two, Macquarie’s dictionary took 11 years.

The Macquarie lexicographers had started work in 1970; the first edition was published in 1981. The 8th edition, published in 2020, and its thesaurus contain more than 300,000 Australian words and definitions.

It is no surprise there were controversies to contend with in the years it took to compile the first edition.

Read more:

Togs or swimmers? Why Australians use different words to describe the same things

Controversies

The test for inclusion of words and expressions is currency. How often do you hear people say, “I’ll see youse later”? That particular Australianism is included in the dictionary because, as an entry explains:

English you does not distinguish singular from plural. The form youse does provide a plural, contrasting with singular you, but there is strong resistance to it, in spoken as well as written language, and it remains non-standard.

Other tests include whether a word is accepted by the language community, whether it’s used extensively, or whether it’s too individual or specialised. Is it likely to stand the test of time? Is the entry well supported by citations?

Language is forever changing, so the challenge for a dictionary is its capacity to remain up to date. Manser amusingly illustrates the growing acceptance of “literally” to be understood as “figuratively” with a quote from Amanda Vanstone:

But I can assure you that we are literally bending over backwards to take into account the concerns raised by colleagues.

Tim Bauer/AAP

As the recipient of elocution lessons in my early education I was fascinated to learn about the dictionary’s engagement with spoken English pronunciation. Then there is the fraught question of the description of iconic foods. Should Lamingtons be dipped only in thin chocolate icing and coconut? Not necessarily. There are pink jelly lamingtons and, more recently, Tokyo lamingtons, which have apparently landed with flavours of matcha and black sesame.

Manser’s least favourite word is mansplain, Word of the year in 2014. She hoped it would be ephemeral … but it was recently just nudged out by “fake news” for word of the decade.

Read more:

The horror and pleasure of misused words: from mispronunciation to malapropisms

A cocktail

The dictionary was launched on 21 September 1981 as The Macquarie Dictionary because it would “add prestige to the dictionary to be associated with a university”, as the Oxford one was.

A special cocktail, the Macquarie, was created to mark the occasion: “Champagne, mango juice, Bitters, Grand Marnier, and a whole strawberry to float on the top”.

The reviews were glowing, except for one condescending and scathing review by the editor of the second edition of the Oxford English Dictionary. Robert Burchfield, a New Zealander, accused the committee of a “charming unawareness of the standards of reputable lexicography outside Australia”.

The new dictionary sold very well: 50,000 copies in its first year and another 50,000 copies over the next 18 months. Within ten years there were 23 spin off editions.

Alan Porritt/AAP

Currently, there are more than 150 spin offs. There was even a Macquarie Bedtime Story Book for Children. There are, of course, other dictionaries of Australian English, such as Oxford University Press’s Australian National Dictionary, a dictionary of Australianisms first published in 1988. There was also an Australian version of the Collins British English Dictionary, which the Macquarie staff regarded as essentially British.

In 1976, the Macquarie offices moved to a former market gardener’s cottage on the campus of Macquarie University. Called “the cottage”, it sounds reminiscent of James Murray’s scriptorium in Oxford, where he oversaw the creation of The Oxford English Dictionary. In 1980, Macquarie Library Pty Ltd became the publisher and has held the copyright ever since, though Macmillan bought the dictionary in 2001.

Macquarie embraced Indigenous Australian issues with Macquarie Aboriginal Words in 1994 and the Macquarie Atlas of Indigenous Australia in 2005. As Ernie Dingo put it at the time: “This book is a White step in the Black direction”.

Manser, who went on to become a high-level public servant, has done painstakingly detailed research for this book, with great support from former colleagues.

It is well written in short chapters. I would have liked to see an index and a time-line, but I hesitate to quibble in the face of such a splendid historical document.![]()

Roslyn Petelin, Course coordinator, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How a mass suicide by slaves caused the legend of the flying African to take off

Victor_Tongdee/iStock via Getty Images

Thomas Hallock, University of South Florida

In May 1803 a group of enslaved Africans from present-day Nigeria, of Ebo or Igbo descent, leaped from a single-masted ship into Dunbar Creek off St. Simons Island in Georgia. A slave agent concluded that the Africans drowned and died in an apparent mass suicide. But oral traditions would go on to claim that the Eboes either flew or walked over water back to Africa.

For generations, island residents, known as the Gullah-Geechee people, passed down the tale. When folklorists arrived in the 1930s, Igbo Landing and the story of the flying African assumed a mythological place in African American culture.

Though the site carries no bronze plaque and remains unmarked on tourist maps, it has become a symbol of the traumatizing legacy of trans-Atlantic slavery. Poets, artists, filmmakers, jazz musicians, griots, novelists such as Toni Morrison and pop stars like Beyoncé have all told versions of the tale.

They’ll often switch up the story’s details to reflect different times and places. Yet the heart of the original tale, one of longing for freedom, beats through each of these retellings. The stories continue to resonate because those yearnings – whether they’re from the cargo hold of a sloop or the confines of a prison cell – remain just as intense today.

Sourcing the story

As an academic trained in literary history, I always look for the reasons behind a story’s origins, and how stories travel or change over time. Variations of the flying African myth have been recorded from Arkansas to Canada, Cuba and Brazil.

Yet even as the many versions cut across the Black diaspora, the legend has coalesced around a single place: St. Simons. An entry in the Georgia Encyclopedia makes a direct correlation between the 1803 rebellion mass suicide and the later, literary folkloric tradition.

Why? One reason is geographic.

St. Simons, part of the archipelago that stretches from Florida to North Carolina, long remained separate from the mainland United States. This isolation allowed African customs to survive, where elsewhere they were assimilated or vanished. Historian Melissa L. Cooper describes the Gullah-Geechee people as cultural conservators, tasked in popular culture with the duties of preservation.

AP Photo/David Goldman

Serendipity also played a role in siting the story. When a causeway from mainland Brunswick to St. Simons was built in 1924, folklorists literally followed a paved route into the past. During the New Deal, the Works Project Administration funded an oral history project that involved interviewing formerly enslaved people, and the flying African story was recorded in “Drums and Shadows,” the classic volume that published interviews from the project.

One Works Project Administration interviewer recorded St. Simons raconteur Floyd White asking, “Heahd about Ibo’s Landing. Das duh place weah dey bring duh Ibos obuh in a slabe ship.”

They “staht singing and de mahch right down in duh ribbuh” – Dunbar Creek – and “mahch back tuh Africa.” But they never get home, White adds: “Dey gits drown.”

Floyd White is a key source on the flying African, though as the hackneyed written transcription of his interview suggests, questions linger. The Ebos, by his account, walk, rather than fly, across the water. White allows that he does not personally believe the myth; he says they drowned.

Stories change, song remains the same

The flying African, despite a genealogy rooted in St. Simons, has no single point of origin. A shifting present continues to rewrite the past. These differences across versions only underscore the strength of the myth’s central core.

Take how music is used. In almost every account of Igbo Landing, the Africans sing before they fly. They chant in a dialect of Bantu, one of Africa’s 500 languages: “Kum buba yali kum buba tambe, / Kum kunka yalki kum kunka tambe.” Those words don’t have a direct translation; the words, more often, get described as secret, magical or lost.

But since the 1960s, in many retellings, the Bantu has been updated to the hymn “Oh Freedom,” an anthem first recorded after the Civil War and later popularized during the civil rights movement.

The storyteller Auntie Zya recounts the Igbo Landing legend in a YouTube post. To make the tale more relevant to children today, she launches into the familiar refrain, “And before I’d be a slave,” using the hymn to bridge the myth and a long struggle for civil rights.

And then there’s Toni Morrison’s novel “Song of Solomon,” the very title of which links music and flight. In the story, the novel’s main character, Milkman Dead, pieces together mysterious lyrics to recover a hidden past. Once he understands the song, he leaps from a Virginia cliff and flies away. Or is it suicide? The ending is famously ambiguous.

Healing through flight

Like all powerful myths, Igbo Landing and the flying African transcend boundaries of time and space.

Experimental filmmaker Sophia Nahli Allison perceives memories from Dunbar Creek as an “ancestral map.” In a poetic narrative she lays over a dance montage, she muses: “Dreams are reality, time is relative, and the past, present, and future are melding together.” Allison suggests that the cross-generational continuity of the myth nurtures her, sustaining her voice through centuries of violence.

Children’s author Virginia Hamilton, likewise, offers the flying African as a script for healing. Her most famous story, “The People Could Fly,” broaches the difficult subject of the Middle Passage, the leg of the slave trade in which Africans, tightly packed in slave ships, were transported across the Atlantic Ocean.

[You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter.]

Hamilton explains why some Africans had to leave their wings behind when forced to America. “They couldn’t take their wings across the water on the slave ships,” she writes. “Too crowded, don’t you know.”

How does a culture get those wings back?

Where some storytellers linger over haunting images, such as the chains supposedly still heard in Dunbar Creek, artists such as Morrison, Allison and Hamilton look forward. Their stories lay the groundwork for recovery.

Hamilton presents “The People Could Fly” as a direct form of hope. In a preface to her collection of that title, she explains how tales “created out of sorrow” carry Black America forward. She reminds readers: “Keep close all the past that was good, and that remains full of promise.” A painful past must be summoned in order to be redeemed.

Igbo Landing starkly illustrated, in 1803, how the choice between slavery and death was not a choice at all. Slavery, sociologist Orlando Patterson wrote, was also social death.

But it’s important to remember that joy doubles as a form of decolonization. Music threads through every version of the flying African legend. Magic words propel fieldworkers into the sky, “Kum yali kum buba tambe.” In song, our spirits lift.

And who among us does not dream of flight?![]()

Thomas Hallock, Professor of English, University of South Florida

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

John Keats’ concept of ‘negative capability’ – or sitting in uncertainty – is needed now more than ever

Dan Kitwood/Getty Images

Richard Gunderman, Indiana University

When John Keats died 200 years ago, on Feb. 23, 1821, he was just 25 years old. Despite his short life, he’s still considered one of the finest poets in the English language.

Yet in addition to masterpieces such as “Ode to a Nightingale” and “To Autumn,” Keats’ legacy includes a remarkable concept: what he called “negative capability.”

The idea – which centers on suspending judgment about something in order to learn more about it – remains as vital today as when he first wrote about it.

Keats lost most of his family members to an infectious disease, tuberculosis, that would take his own life. In the same way the COVID-19 pandemic turned the worlds of many people upside down, the poet had developed a deep sense of life’s uncertainties.

Keats was born in London in 1795. His father died in a horse-riding accident when Keats was eight years old, and his mother died of tuberculosis when he was 14. As a teenager, he commenced medical studies, first as an apprentice to a local surgeon and later as a medical student at Guy’s Hospital, where he assisted with surgeries and cared for all kinds of people.

After completing his studies, however, Keats decided to pursue poetry. In 1819, he composed many of his greatest poems, though they didn’t receive widespread acclaim during his lifetime. By 1820, he had contracted tuberculosis and relocated to Rome, where he hoped the warmer climate would help him recover. He ended up dying a year later.

The Print Collector via Getty Images

Keats coined the term negative capability in a letter he wrote to his brothers George and Tom in 1817. Inspired by Shakespeare’s work, he describes it as “being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.”

Negative here is not pejorative. Instead, it implies the ability to resist explaining away what we do not understand.

Rather than coming to an immediate conclusion about an event, idea or person, Keats advises resting in doubt and continuing to pay attention and probe in order to understand it more completely. In this, he anticipates the work of Nobel laureate economist Daniel Kahneman, who cautions against the naïve view that “What you see is all there is.”

It is also a good idea to take the time to look at matters from multiple perspectives. Shakespeare’s comedies are full of mistaken identities and misconceptions, including mixed-up genders. Keats reminds us that we are most likely to gain new insights if we can stop assuming that we know everything we need to know about people by neatly shoehorning them into preconceived boxes.

Negative capability also testifies to the importance of humility, which Keats described as a “capability of submission.” As Socrates indicates in Plato’s “Apology,” the people least likely to learn anything new are the ones who think they already know it all. By contrast, those who are willing to question their own assumptions and adopt new perspectives are in the best position to arrive at new insights.

Keats believed that the world could never be fully understood, let alone controlled. In his view, pride and arrogance must be avoided at all costs, an especially apt warning as the world confronts challenges such as climate change and COVID-19.

At the same time, information technology seems to give everyone instant access to all human knowledge. To be sure, the internet is one gateway to knowledge. But it also indiscriminately spreads misinformation and propaganda, often fueled by algorithms that profit off division.

This, it goes without saying, can cloud understanding with false certainty.

And so our age is often described as polarized: women versus men, Blacks versus whites, liberals versus conservatives, religion versus science – and it’s easy to automatically lapse into the facile assumption that all human beings can be divided into two camps. The underlying view seems to be that if only it can be determined which side of an issue a person lines up on, there’s no need to look any further.

Against this tendency, Keats suggests that human beings are always more complex than any demographic category or party affiliation. He anticipates another Nobel laureate, writer and philosopher Alexander Solzhenitsyn, who wrote that instead of good guys and bad guys, the world is made up of wonderfully complex and sometimes even self-contradictory people, each capable of both good and bad:

If only it were all so simple! If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being. And who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart?

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Uncertainty can be uncomfortable. It is often quite tempting to stop pondering complex questions and jump to conclusions. But Keats counsels otherwise. By resisting the temptation to dismiss and despise others, it’s possible to open the door to discovering traits in people that are worthy of sympathy or admiration.

They may, with time, even come to be regarded as friends.![]()

Richard Gunderman, Chancellor’s Professor of Medicine, Liberal Arts, and Philanthropy, Indiana University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How reading aloud can be an act of seduction

Kiera Vaclavik, Queen Mary University of London

Reading aloud is an activity that we associate with the cosy comfort of children’s bedtime stories. Certainly, children’s classics from The Gruffalo to the Alice books are produced knowing that when they come to be read, the chances are that an older person will be reading them aloud to a younger one.

The extensive benefits of reading aloud to children are well documented. Researchers have found that toddlers who are read to become children who are “more likely to enjoy strong relationships, sharper focus, and greater emotional resilience and self-mastery”.

Unsurprisingly, then, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends reading aloud to children. It’s even used by sociologists as one of the most important indicators of life prospects.

But if reading aloud is so good for us, why has it become primarily the preserve of childhood?

How silent reading took over

Of course it wasn’t always this way. As Meghan Cox Gurdon, the Wall Street Journal’s Children’s book critic, points out, since the advent of the written word until the 10th century, “to read at all was to read aloud”.

Even after silent reading became more common, it co-existed with what English Literature professor Abigail Williams refers to as “communal” and “social” forms of reading well into the 19th century. Only when the voices of mass media entered the home through radio and TV sets did reading as a shared public activity between consenting adults specifically start to wane.

Robert Kneschke/Shutterstock

But as books themselves reveal, reading aloud could be more than merely sociable. It can be deeply seductive, forging intimate as well as communal bonds.

Azar Nafisi’s memoir about life as a woman and as a literature teacher in post-revolutionary Iran, Reading Lolita in Tehran (2003), features students Manna and Nima, who “had fallen in love in large part because of their common interest in literature”. If a love of literature draws this couple together, it’s reading it aloud that cements their relationship. The words they read aloud conjure a safe space from the difficulties of their word.

Likewise, in Mansfield Park (1814), Jane Austen uses reading aloud as a highly charged turning point in the relationship between protagonist Fanny Price and her recently declared suitor, Henry Crawford. When Henry reads aloud to the gathered assembly, his skill and sensitivity is such that Fanny is forced to sit up and listen despite herself.

Her needlework, upon which she determinedly focuses all her attention at first, eventually drops into her lap “and at last … the eyes which had appeared so studiously to avoid him throughout the day were turned and fixed on Crawford, fixed on him for minutes, fixed on him in short till the attraction drew Crawford’s upon her, and the book was closed, and the charm was broken.”

This insistent repetition makes for fairly steamy stuff in the Regency drawing room.

Reading as seduction

Elsewhere, reading aloud goes beyond such (ultimately unsuccessful) wooing. Spoiler alert: Crawford scuppers his chance with Fanny and runs away with her (already married) cousin (gasp!).

In Bernhard Schlink’s The Reader (1997), reading aloud underpins the relationship between the narrator, Michael, and his much older lover, Hanna – played in the 2008 film adaptation by David Kross/Ralph Fiennes and Kate Winslet.

Whether to keep Michael on track, or out of pure self-interest, Hanna insists that Michael read to her before they make love. Only much later do Michael and the reader discover that Hanna has two secrets (spoiler alert): she is a former concentration camp guard and she is illiterate.

Here, reading aloud is not just the warm-up act but an integral part of an intimate “ritual of reading, showering, making love and lying beside each other”. Reading unites these two very different individuals both physically and emotionally. Much later, when Hanna is imprisoned for war crimes, Michael continues to read to her from a distance; the taped recordings he sends ultimately allowing her to learn to read herself.

The unhappy fates of some of these relationships show that reading aloud is not a one-way ticket to the happily ever after. But these scenes do reveal its deep sensuality. According to Gurdon, the Wall Street Journal’s Children’s book critic, “there is incredible power in this fugitive exchange”.

Gurdon also suggests that reading aloud “has an amazing capacity to draw us closer to one another” both figuratively and literally. Where solitary reading drives us into ourselves – producing the cliched image of the couple reading their own books in bed before rolling over and turning out the light – reading aloud is a shared experience.

Reading aloud takes longer, but that is part of the point. Slow reading is sensuous reading. As opposed to the audiobooks now so firmly a part of the cultural landscape, for adults as well as children, reading aloud is responsive, intuitive and embodied.

The reader is also an observer, who adapts gestures, facial expressions and intonation in response to cues. Listeners observe too of course, their attention centred on the person before or alongside them.

With conversation petering out after months of lockdown and no restaurants, museums and cinemas to go to for some time yet, it’s worth remembering that learning and romance are still to be found under the (book) covers … as long as we read the words aloud.![]()

Kiera Vaclavik, Professor of Children’s Literature & Childhood Culture, Queen Mary University of London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.