The link below is to an article that takes a look at the health implications of being a female librarian in the Victorian era.

For more visit:

https://daily.jstor.org/being-librarian-dangerous/

The link below is to an article that takes a look at the health implications of being a female librarian in the Victorian era.

For more visit:

https://daily.jstor.org/being-librarian-dangerous/

publicdomainpictures

Stephanie Palmer, Nottingham Trent University

The season of the good old summer “fayre” is here and many UK readers will be heading off to eat tea and scones and take part in the tombola at their local village fete. There, it’s a good bet, they will hear of local people’s concerns that new housing developments foisted on them by the government will ruin the character of their idyllic rural community.

But the myth of tranquil village life was well and truly exploded in the Victorian age when many writers concluded that life in England’s small rural communities was not a simple idyll of tea, vicars and charitable works.

For many people, especially those who may not have visited the UK, the most accessible pictures of village life are those painted in novels: who can forget the timeless portrait of life in a sleepy Dorset community in PG Wodehouse’s Blandings series, or EF Benson’s Mapp and Lucia books, set in a fictional Sussex village? But fiction has also been highlighting the negatives of village living for more than a century.

The “greetings card” scenario of village life was established early. In her memoir Our Village (published in five volumes between 1824 and 1832), Mary Mitford – who lived at Three Mile Cross near Reading in Berkshire – gives us a classic rendition of peaceful village life. There are quaint depictions of servants, chaste suitors, elderly brides and grooms, blacksmiths and gypsy fortune tellers.

Our Village contains all the myths of village life. Everyone is familiar: a village is a little world “where we know everyone, are known to everyone, interested in everyone, and authorised to hope that everyone feels an interest in us”. There are no newcomers, nobody is systematically excluded and nobody is living a secret or misunderstood life. Poverty is relegated to the margins – there’s only the occasional mention of the workhouse and, Mitford assures her readers, the village is a collection of cottages, not “fine mansions finely peopled”.

But even in the 1820s, such a village felt under threat from the railways, improved roads and the increasing size of the towns of the industrialised North. And no sooner did Mitford complete Our Village than other authors began to parody or correct her vision.

Elizabeth Gaskell’s Cranford (1853) is a gentle text still very positive about life in a confined locality. Although Cranford is a town outside “Drumble” – her stand-in for Manchester – it resembles Mitford’s village in that everyone knows each other and the narrative is focused on a limited set of characters. In the case of this novel – and so many others in the tradition – the main characters are women, and it is women’s unpaid labour that makes the community run smoothly. Yet Gaskell gently mocks her characters, Matty Jenkyns, Miss Pole, and Mrs Jamieson, for their conventionality, triviality and timidity.

The women follow strict social rules – an entire chapter revolves around whether these august personages should stoop to visit a former ladies’ maid who has set up a milliner’s shop and hence was “in trade”. In another chapter, the women grow fearful of outsiders when they hear of a cluster of burglaries in the neighbourhood, which proves to be founded on rumour.

Thomas Hardy’s villages such as Weatherbury in Far from the Madding Crowd (1874) or Marlott in Tess of the D’Urbervilles (1891) are idyllic in some ways, but not in others. Shepherds are close enough to nature to saunter out of their huts at night to tell the time by stars, and the slow pace of life allows for ample opportunity for community and flirtation. Yet sexual transgressions are treated to the full judgement of an unforgiving community, and questions of money and class interrupt any readers’ expectations of rural bliss.

These books sold well in the US, even though villages there were subject to dramatic population shifts westward and industrial development. Writers in the US sought to reinforce or contest Mitford’s vision.

After reading Mitford and migrating to a new village in Michigan, Caroline Kirkland wrote A New Home, Who’ll Follow? (1839), which mercilessly satirised her vulgar frontier neighbours and the wealthier eastern newcomers. When her neighbours read the novel, they ostracised her – and she never wrote anything as trenchant again.

Although the American regionalism that flourished in the latter quarter of the 19th century is known for romantic visions of village life, upon closer examination, key writers such as Sarah Orne Jewett and Mary E Wilkins Freeman reveal many of village life’s negatives.

If Gaskell acknowledges in Cranford that her ladies’ kindness to the poor is “somewhat dictatorial”, Freeman’s A Mistaken Charity (1883) takes this point to its logical conclusion. Two elderly sisters living happily in their dilapidated cottage are visited by Mrs Simonds, a woman who is “a smart, energetic person, bent on doing good”. Mrs Simonds arranges to take Charlotte and Harriet to the poorhouse, where they are forced to wear lace caps and sit indoors. Charlotte and Harriet run away.

By the 1910s, there was a literary “revolt from the village”, and writers including Sherwood Anderson focused on the sexual repression of small town life. Although Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio, published in 1919, is set in a town, it is a town of 1,800 people, far smaller than many British villages today. Meanwhile, Stella Gibbons parodied rural melodramas in Cold Comfort Farm (1932), in which, instead of graciously fitting in like the urban narrators of Jewett’s fiction, Flora Poste, a visitor from London, forces the members of a dysfunctional family to follow their individual desires rather than their family destiny.

![]() According to these writers, villages can be conformist, unimaginative, repressive, nepotistic. These fictions imply that villages will be harder to maintain now that women have other outlets for their energies. The negatives come from the same source as the positives in village life, and people who wish to defend villages, and the tradition of rural living, should remember this literary ambivalence and the fact that it has gone on for more than 100 years.

According to these writers, villages can be conformist, unimaginative, repressive, nepotistic. These fictions imply that villages will be harder to maintain now that women have other outlets for their energies. The negatives come from the same source as the positives in village life, and people who wish to defend villages, and the tradition of rural living, should remember this literary ambivalence and the fact that it has gone on for more than 100 years.

Stephanie Palmer, Senior Lecturer, School of Arts & Humanities, Nottingham Trent University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Anne-Marie Evans, York St John University

The reviews have not always been kind. The texts are rarely perceived as “literary” or even particularly important – so they don’t get taken seriously. But the celebrity “femoir” – a memoir authored by a well-known female actor or comedian – has become a staple of the publishing trade over the last few years.

As I explain in a recent book chapter, the femoir occupies an important place in contemporary women’s writing because they promote female empowerment. The books also embrace body positivity, and address the importance of having a supportive female community of friends.

These women writers already have hugely successful careers before they begin to write their femoirs. Lena Dunham, for example, was the creator, writer, star, and sometimes director of the hit HBO series Girls – which received a range of Emmy awards and nominations. Amy Poehler and Tina Fey are both veterans of Saturday Night Live, and Fey was the creator, writer, and star of 30 Rock, while Poehler starred in the hugely popular Parks and Recreation. Mindy Kaling, on the other hand, was the first Indian American woman to both star in and produce her own show, The Mindy Project. So why this sudden need to tell their story in print?

One reason might be that writing, and autobiography in particular, is a great way for women to develop their public brand. Suzanne Ferris, who has researched and published on popular women’s writing, compares the femoir to chick lit – as this new style of memoir often follow the traditional structure of a female protagonist overcoming various personal and professional obstacles.

The reader might hear about one of Kaling’s bad dates, or about Fey’s struggles to balance being a mother and being a professional working woman. But within the genre, each writer also emphasises professional advancement over personal success.

None of these books ever offer any real details about the women’s personal lives beyond a few anecdotes that could be shared on a late night talk show. But the femoir offers the reader the illusion they are being told highly privileged information, and this is hugely important part of the genre’s appeal.

For Dunham, Fey, Poehler and Kaling, writing has always been an important part of their career. Although they are famous for performing, most of them started out as writers. Kaling, for example, got her break as a one of the writers for the US version of The Office.

Writing for The Guardian Hadley Freeman suggests that the main difference between memoir and femoir is the construction of the narrative voice. A memoir is usually published because the story is special or unique, but the very appeal of the femoir is that its writer is – apparently – just like the imagined (female) reader.

As a narrative voice, the author of the femoir must be funny and relatable. She must be every woman to every reader, or her book will not be successful. This is a hugely important part of the brand. A femoir is not meant to be a weighty autobiography but instead is designed to be a fun and entertaining read.

As well as a life story, a femoir nearly always features some kind of interactive element. Amy Poehler’s Yes Please is broken up with collages and photos, and there are even several sections where the reader can make her own notes, suggesting an even closer imagined affinity between celebrity narrative voice and the reader.

Men, of course, are rarely asked to account for their professional achievement. But for these authors, telling their story becomes a useful way for female comedians to explain their brand and recount their successes.

One of the most striking features of the femoirs is how much the writers tend to reference other female writers in the genre. There is a lot of emphasis on how important it is to have the support of other women. Fey, for example, writes several “love letters” to her friend and frequent collaborator, Poehler, encouraging the idea that female community is central to individual female accomplishment.

There are, of course, a lot of criticisms to be made of the femoir. They are highly performative types of writing, they are designed to be commercial, and some of them have clearly been helped along by ghost writers. But the genre is still hugely popular and several UK performers – Caitlin Moran, Sara Pascoe, Sarah Millican – have joined the ranks in recent years.

![]() Although femoirs are often dismissed as celebrity memoir (which is undeniably what they are) it is sometimes forgotten that many of these women all wrote their own material for the stage and screen long before they began to write a version of their autobiographies. The femoir is just their latest medium.

Although femoirs are often dismissed as celebrity memoir (which is undeniably what they are) it is sometimes forgotten that many of these women all wrote their own material for the stage and screen long before they began to write a version of their autobiographies. The femoir is just their latest medium.

Anne-Marie Evans, Subject Director: English Literature, York St John University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Stacy Gillis, Newcastle University

Women’s writing has long been a thorn in the side of the male literary establishment. From fears in the late 18th century that reading novels – particularly written by women – would be emotionally and physically dangerous for women, to the Brontë sisters publishing initially under male pseudonyms, to the dismissal of the genre of romance fiction as beyond the critical pale, there has been a dominant culture which finds the association of women and writing to be dangerous. It has long been something to be controlled, managed and dismissed.

One of the ways that publishers, booksellers and critics use to “manage” literature is through the notion of genre: labelling a book as “detective fiction” becomes an easy way to identify particular tropes in a novel. These genre designations are particularly helpful for publishers and booksellers, with the logic running something like this: a reader can walk into any bookstore, anywhere, and go to the detective fiction section and find a book to read, because s/he has read detective fiction before and enjoyed it.

What complicates this is who makes the decision of which genres are deemed to be appropriate, and which books are put into which category. Genre is also complicated by the idea of women’s writing. Can we have a genre that is designated solely by the sex of the author? What if we turned this around, and rather than a genre, women’s writing was a term we used to simply celebrate writing about women?

Here are five novels by women – and about women – from across the 20th century. These novels all grapple, in very different ways, with women and independence.

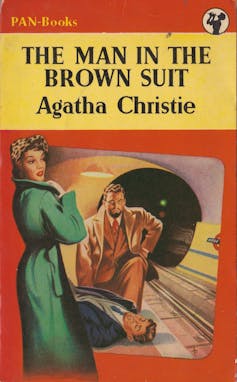

Anna Beddingfeld, a self-mocking heroine, who is very aware of the conventions of gender and genre, impulsively buys a ticket to South Africa because the boat fare is the exact amount she has left in the world. She ends up taking down an international crime syndicate with aplomb and panache.

Doss is the expendable unmarried older woman in a Victorian novel. But in this story, she walks out on her largely uninterested family to move into a cabin on an island with a man she has met only briefly. A fantasy of the Canadian wilderness, the novel was one of Montgomery’s few novels for adults.

A rewriting of Jane Eyre, the novel contains all the tropes of the Gothic romance – a castle, a family secret, murder – but these are challenged by one of Stewart’s finest protagonists, Linda Martin. Martin is employed as a governess by an aristocratic family, but rejects the trappings of romance to protect her charge, and her own integrity.

Edana Franklin wakes up in hospital with her arm amputated and the police questioning her husband. It is revealed that she has been travelling back to 1815, where she comes into repeated contact and conflict with Rufus, one of her slave-owning ancestors. A novel that raises important questions about masculinity, power and violence.

One of the earliest pieces of electronic fiction, this retelling of Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) and Baum’s The Patchwork Girl (1913) places the narrative in the hands of the reader, who pieces together the story through illustrations of parts of a female body.

Often popular novels by women have a narrative arc that is visible from the outset: the protagonists will find a romantic partner in the end. In some of the above books, some of the women do, and some of them don’t, find a romantic partner. For those who do, the romance is secondary to the work they do, and the choices that they make about their own lives.

What unites the novels is an exploration of the choices that some women have to make as a result of their sexed and gendered embodiment, whether travelling to South Africa on a whim, being jolted unwillingly back onto a slave plantation, or making an explicit call to the (woman) reader to make choices about how the electronic story develops.

![]() Writing about women (and often by women) gives us some examples of how to challenge the status quo, if only for a little while. Each challenge, however, provides another example of how to effect change in a patriarchal culture. Here’s to the writers about women who have done this – from Jane Austen to Shirley Jackson, from Frances Burney to Josephine Tey, and from Angela Carter to Val McDermid.

Writing about women (and often by women) gives us some examples of how to challenge the status quo, if only for a little while. Each challenge, however, provides another example of how to effect change in a patriarchal culture. Here’s to the writers about women who have done this – from Jane Austen to Shirley Jackson, from Frances Burney to Josephine Tey, and from Angela Carter to Val McDermid.

Stacy Gillis, Lecturer in Modern and Contemporary Literature, Newcastle University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.