Marco Rosario Venturini Autieri/Getty

Rachel Hadas, Rutgers University Newark

Pondering the now no-longer Dixie Chicks – renamed “The Chicks” – Amanda Petrusich wrote in a recent issue of the New Yorker, “Lately, I’ve caught myself referring to a lot of new releases as prescient – work that was written and recorded months or even years ago but feels designed to address the present moment. But good art is always prescient, because good artists are tuned into the currency and the momentum of their time.”

That last phrase, “currency and momentum,” recalls Hamlet’s advice to the actors visiting the court of Elsinore to show “the very age and body of the time his form and pressure.” The shared idea here is that good art gives a clear picture of what is happening – even, as Petrusich suggests, if it hadn’t happened yet when that art was created.

Good artists seem, in our alarming and prolonged time (I was going to write moment, but it has come to feel like a lot more than that), to be leaping over months, decades and centuries, to speak directly to us now.

‘Riding into the bottomless abyss’

Some excellent COVID-19-inflected or anticipatory work I’ve been noticing dates from the mid-20th century. Of course, one could go a lot further back, for example to the lines from the closing speech in “King Lear”: “The weight of this sad time we must obey.” Here, though, are a few more recent examples.

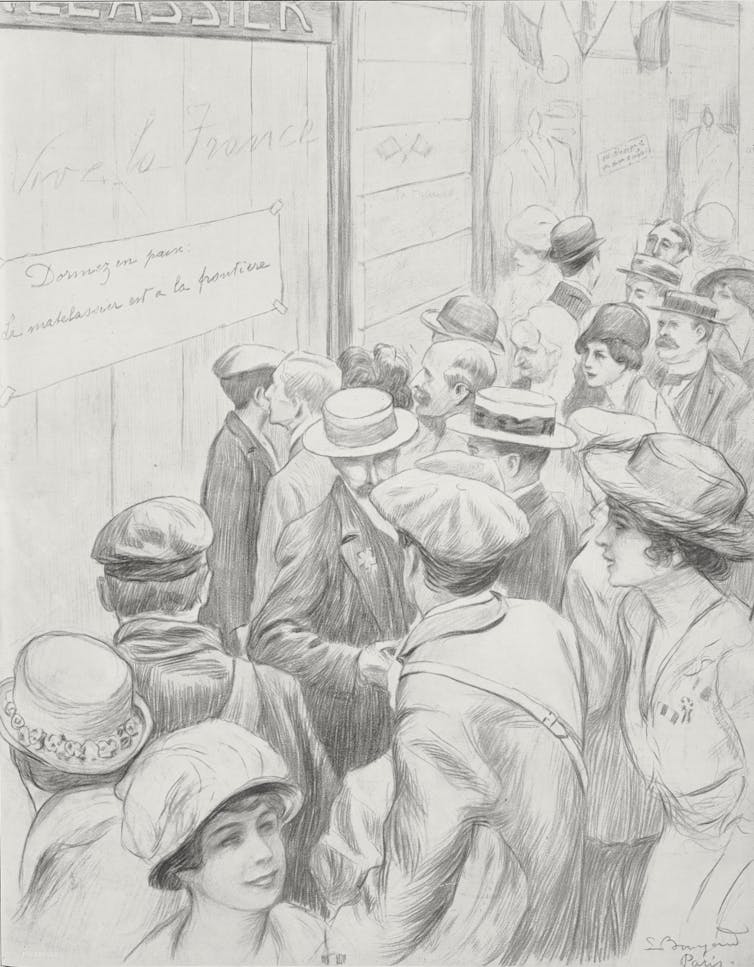

L. Bombard, from L’Illustrazione Italiana/Getty

Marcel Proust’s “Finding Time Again,” an evocation of wartime Paris from 1916, strongly suggests New York City in March 2020: “Out on the street where I found myself, some distance from the centre of the city, all the hotels … had closed. The same was true of almost all the shops, the shop-keepers, either because of a lack of staff or because they themselves had taken fright, having fled to the country, and left the usual handwritten notes announcing that they would reopen, although even that seemed problematic, at some date far in the future. The few establishments which had managed to survive similarly announced that they would open only twice a week.”

I recently stumbled on finds from the 1958 edition of Oscar Williams’ “The Pocket Book of Modern Verse” – both, strikingly, from poems by writers not now principally remembered as poets. Whereas a fair number of the poets anthologized by Williams have slipped into oblivion, Arthur Waley and Julian Symons speak to us now, to our sad time, loud and clear.

From Waley’s “Censorship” (1940):

It is not difficult to censor foreign news.

What is hard to-say is to censor one’s own thoughts,-

To sit by and see the blind man

On the sightless horse, riding into the bottomless abyss.

And from Symons’ “Pub,” which Williams doesn’t date but which I am assuming also comes from the war years:

The houses are shut and the people go home, we are left in

Our island of pain, the clocks start to move and the powerful

To act, there is nothing now, nothing at all

To be done: for the trouble is real: and the verdict is final

Against us.

‘Return to what remains’

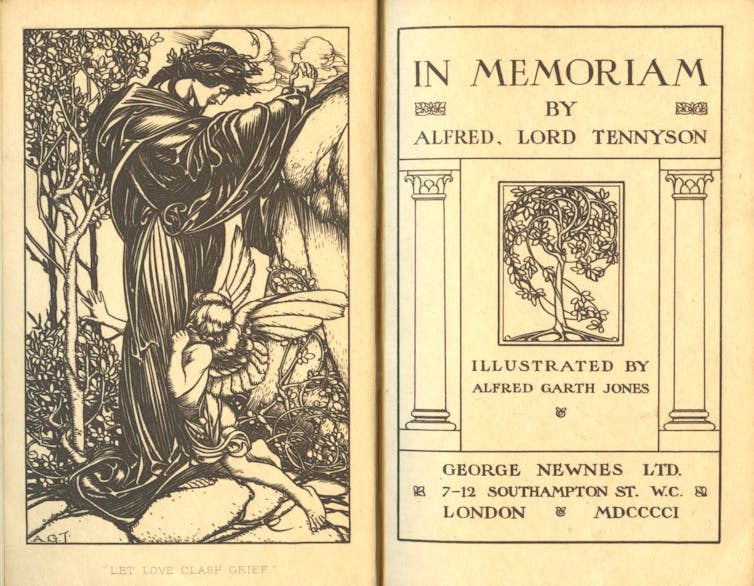

Hulton Archive/Getty

Dipping a bit further back, into Henry James’ “The Spoils of Poynton” from 1897, I was struck by a sentence I hadn’t remembered, or had failed to notice, when I first read that novella decades ago: “She couldn’t leave her own house without peril of exposure.” James uses infection as a metaphor; but what happens to a metaphor when we’re living in a world where we literally can’t leave our houses without peril of exposure?

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

In Anthony Powell’s novel “Temporary Kings,” set in the 1950s, the narrator muses about what it is that attracts people to reunions with old comrades-in-arms from the war. But the idea behind the question “How was your war?” extends beyond shared military experience: “When something momentous like a war has taken place, all existence turned upside down, personal life discarded, every relationship reorganized, there is a temptation, after all is over, to return to what remains … pick about among the bent and rusting composite parts, assess merits and defects.”

The pandemic is still taking place. It’s too early to “return to what remains.” But we can’t help wanting to think about exactly that. Literature helps us to look – as Hamlet said – before and after.![]()

Rachel Hadas, Professor of English, Rutgers University Newark

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.