Shih-Wen Sue Chen, Deakin University; Kristine Moruzi, Deakin University, and Paul Venzo, Deakin University

With remarkable speed, numerous children’s books have been published in response to the COVID-19 global health crisis, teaching children about coronavirus and encouraging them to protect themselves and others.

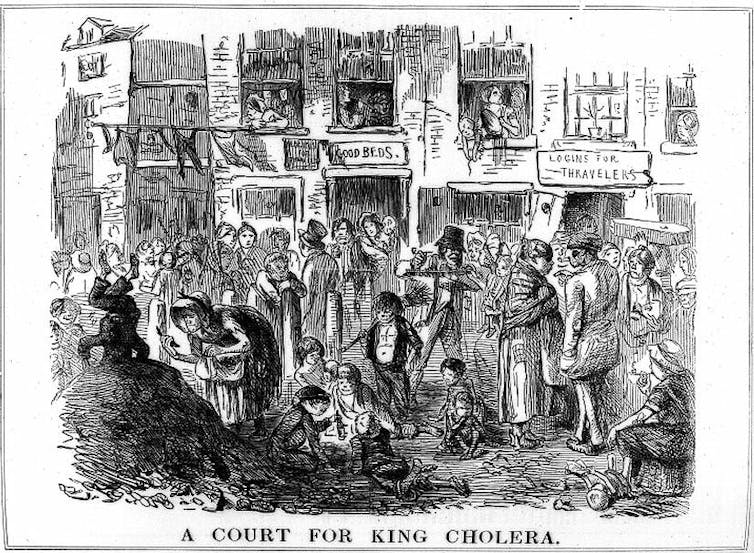

Children’s literature has a long history of exploring difficult topics, with original fairy tales often including gruesome imagery to teach children how to behave. Little Red Riding Hood was eaten by the wolf in a warning to young ladies to be careful of men. Cinderella’s stepsisters had their eyes pecked out by birds as punishment for wickedness.

More recently, picture books have dealt with issues including September 11, the Holocaust, environmental issues and death.

But this wave of coronavirus books is unique, being produced during a crisis rather than in its aftermath.

Many have been written and illustrated in collaboration between public health organisations, doctors and storytellers, including Hi. This is Coronavirus and The Magic Cure both produced in Australia.

These books explore practical ways young children can avoid infection and transmission, and provide strategies parents can use to help children cope with anxiety. Some books feature adult role models, but the majority feature children as heroes.

The best of these books address children not just as people who might fall ill, but as active agents in the fight against COVID-19.

Our top picks

Coronavirus: A Book for Children

Written in consultation with an infectious diseases specialist and illustrated by Axel Scheffler of The Gruffalo, this nonfiction picture book offers children information about transmission, symptoms and the possibility of a cure, reassuring readers that doctors and scientists are working on developing a vaccine.

The last few pages answer the question “what can I do to help?”

Coronavirus: A Book for Children shows a diversity of characters taking action to manage the effects of the virus. Children are told to practice good hygiene, not to disturb their parents while they are working from home and keep up with their schoolwork.

It is also hopeful: reinforcing the idea that the combination of scientific research and practical action will lead to a point when “this strange time will be over”.

My Hero is You! How kids can fight COVID-19

Written and illustrated by Helen Patuck, My Hero is You! is an initiative of a global reference group on mental health, and is a great book for parents to read with their children.

Sara, daughter of a scientist, and Ario, an orange dragon, fly around the world to teach children about the coronavirus.

Ario teaches the children when they feel afraid or unsafe, they can try to imagine a safe place in their minds.

Based on a global survey of children and adults about how they were coping with COVID-19, My Hero is You! translates the results of this comprehensive survey into a reassuring story for kids experiencing fear and anxiety. It also acknowledges the global nature of the health crisis, showing children they are not alone.

The Princess in Black and the Case of the Coronavirus

The Princess in Black is an existing series, with seven books published since 2014 and over one million copies sold. In the books, Princess Magnolia enlists children to help with a problem she cannot defeat alone: here, of course, that problem is coronavirus.

For fans of the series, Magnolia and her pals are familiar characters encouraging readers to solve the problem of coronavirus by washing their hands, staying at home, and keeping their distance.

The Princess in Black shows a deft use of humour to introduce children to complex ideas in a familiar and friendly manner.

Little heroes

Children’s books have often sought to entertain and educate children at the same time. The immediacy of these books, with their practical solutions and strategies for children to manage fears and anxieties about sickness and isolation, is a phenomenon we haven’t seen before.

With free online distribution and simple messages, these books present children with individual actions that have both personal and collective benefits.

Importantly, the heroes identified in these stories include children themselves. Their fears are acknowledged, but at the same time they are told they can fight the virus successfully.

A frequently updated list of children’s books on the pandemic is available from the New York School Library System’s COVID-19 page.![]()

Shih-Wen Sue Chen, Senior Lecturer in Writing and Literature, Deakin University; Kristine Moruzi, Research fellow in the School of Communication & Creative Arts, Deakin University, and Paul Venzo, , Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.