The link below is to an article that takes a look at the importance of getting food right in fiction.

For more visit:

https://lithub.com/the-importance-of-getting-food-right-in-fiction/

The link below is to an article that takes a look at the importance of getting food right in fiction.

For more visit:

https://lithub.com/the-importance-of-getting-food-right-in-fiction/

The link below is to an article that takes a look at microfiction and four sites that provide it.

For more visit:

https://lithub.com/looking-for-a-quick-read-here-are-4-literary-sites-that-publish-great-microfiction/

Cynthia Spada, University of Victoria

Beyond the viral contagion of COVID-19, the pandemic’s accompanying social and economic hardships have challenged many people’s physical and mental wellness. Over the past year of navigating living in a pandemic, it’s become clear that relationships matter to health: relationships between body and mind, between neighbours and between individuals and their societies.

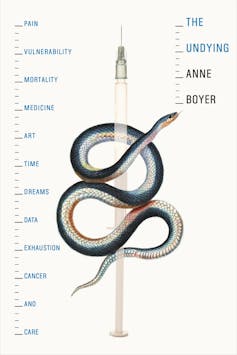

Literature was dissecting these connections long before the outbreak. Recent memoirs, non-fiction, fiction, poetry and graphic novels related to physical and mental health examine not just the fragility of individuals but how individuals relate to social and power structures like capitalism, racism or colonialism. Writers have also explored how people’s social roles and identities shape their relationships to narrative itself. As American poet and memoirist Anne Boyer writes in her Pulitzer Prize-winning memoir, The Undying, “I do not want to tell the story of cancer in the way that I have been taught to tell it.”

For several years, I have been researching, writing about and teaching literary texts related to maladies like depression, substance abuse and cancer. I’m interested in how narratives about health published today explore the interdependence of bodies and their environments in a way that may teach us important lessons during the pandemic, and beyond it.

Since the 1960s, critiques of medical education, medical ethics and the role of narrative in healing have meant an emerging awareness of how the medical field can be allied with literature.

Some medical schools are requiring students to take literature courses to become more adept with reading patients’ stories; some students take my contemporary literature course at University of Victoria to satisfy a medical school course requirement. The convergence of these two fields is helping to disrupt the canonical “literature of madness.”

Starting in the 1970s, mental illness became a hot topic in literature departments. Books like Shoshana Felman’s Writing and Madness and Lillian Feder’s Madness in Literature marked the new interest.

In “Literature of Madness” courses at various universities, students studied Dostoyevsky’s The Double, Charlotte Perkin Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper,” Ken Kesey’s One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar.

These health stories pit mentally ill characters against individual antagonists like husbands, mothers, doctors and nurses, or, fighting oneself as seen through the ancient literary theme of the double or dopplegänger (as in Dostoyevsky’s tale). Yet some critics have also explored how these narratives examine individuals battling formidable but intangible foes, and thus comment on social ills: For example, patriarchy in The Bell Jar

and “The Yellow Wallpaper.”

Many recent health narratives today are questioning how well-being is damaged by social determinants of health like income inequality and racism. They are also examining how health relates to phenomena like capitalism and climate change, which are elusive but all-pervasive.

For instance, Boyer damns the American health-care system, with its outrageous costs and lack of guaranteed sick leave, but also capitalism as a whole. For her, like Susan Sontag, cancer infuses culture as much as human bodies, but economic pressures also cast a huge shadow.

Blending personal experience and big-picture analysis can be found in other recent health memoirs. In The Recovering: Intoxication and Its Aftermath, American writer Leslie Jamison discusses her own experiences of alcoholism as a white woman alongside the racism of the American criminal justice system. As she observes: “White addicts get their suffering witnessed. Addicts of colour get punished.”

The best-selling essay collection A Mind Spread Out on the Ground, by Tuscarora writer Alicia Elliott, examines

how systematic oppression of Indigenous communities is linked to depression.

Her settler therapist can’t understand why she’s depressed, and none of her self-help books actually help.

She writes of one, “There is nothing in the book about the importance of culture, nothing about intergenerational trauma, racism, sexism, colonialism, homophobia, transphobia.”

This interest in the social determinants of health isn’t limited to non-fiction. Sabrina by American cartoonist Nick Drnaso is a 2018 graphic novel that was longlisted for the 2018 Man Booker Prize. Sabrina takes stock of what appears to be PTSD and depression in a political climate of misinformation and conspiracy theories.

As one character fills out a daily wellness report, the reader may realize anyone would feel depression and anxiety in such a world.

Meanwhile, Fady Joudah, a Palestinian American poet and practising doctor, weighs economic inequity and a lack of sustainability in “Corona Radiata,” a poem about COVID-19 published last March. “Corona Radiata” argues that we need to understand health as contingent on relationships between humans — and between humans and other living things. Joudah suggests that:

“Far and near the virus awakens

in us a responsibility

to others who will not die

our deaths, nor we theirs,

though we might …”

He’s right, if hopeful. Until the vaccine is widely distributed, public health will depend on our ability to understand ourselves as part of an inconceivably vast network.

American novelist Richard Powers’s The Overstory, which won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 2019, also unites health with responsibility. In the novel, characters challenged by physical disabilities and strokes find ways to communicate with and through nature. A scientist almost dies by suicide early in the novel before recommitting herself to loving as well as studying the trees. Environmental activism gives them purpose, even if it doesn’t heal them.

British writer Robert Macfarlane has proposed that the environmental crisis will continue to transform our literature and art. Many recent works support his idea. In particular, the latest health literature fuses various genres, including memoir, biography, reportage, literary and cultural criticism, science writing and prose poetry.

The new health literature also reminds us that our health and the planet’s are inextricably linked. In the near future, this genre is likely to increasingly address the impact of climate change on our physical and mental well-being, such as the rise in eco-anxiety. I think we’ll see a blending of literature, medicine and environmental studies more and more often.

Some researchers have noted a link between reading and longevity in individuals. Reading health literature may spur us to support longevity for the Earth too.![]()

Cynthia Spada, Sessional Lecturer in the Department of English, University of Victoria

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Nada Elnahla, Carleton University and Ruth McKay, Carleton University

Reading fiction has always been, for many, a source of pleasure and a means to be transported to other worlds. But that’s not all. Businesses can use novels to consider possible future scenarios, study sensitive workplace issues, develop future plans and avoid unplanned problematic events — all without requiring a substantial budget.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many business leaders have learned how important it is for businesses to consider a wide range of possible outcomes and to enhance organizational adaptability. Relying on analyzing or projecting trends and extending what business leaders usually do is no longer enough to assure future success. When management is poorly prepared for the unexpected, businesses start getting into trouble.

Scenario planning, therefore, helps businesses keep themselves flexible and move quickly with market shifts. Scenario planning is a series of potential stories or possible alternate futures in which today’s decisions may play out. Such planning can help managers assess how they or their employees should respond in different potential situations.

Unfortunately, scenario planning requires time and resources. And depending on its use, such as for an investigation, budgeting or legal matters, it can also require collecting sensitive data. That can include employees’ personal experiences of sexual, discriminatory or psychological harassment, suicide, mental health, drug abuse, etc.

The more sensitive the needed data is, the more difficult it is to collect while ensuring employee privacy. This is where literary texts come in.

As sources for possible future scenarios capable of providing strategic foresight, or producing alternative future plans, novels can also help businesses create dialogue on difficult and even taboo subjects.

Novels are, therefore, capable of helping managers become better, providing them with creative insight and wisdom. Science fiction can provide a means to explore morality tales, a warning of possible futures, in an attempt to help us avoid or rectify that future.

Our research

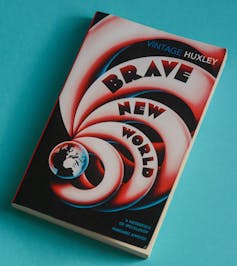

uses Aldous Huxley’s 1932 novel Brave New World to explore possible scenarios related to situations that are usually kept confidential, such as employees’ mental health issues and drug use or abuse. We examined how employers encounter uncertainty around the impact that legalizing cannabis could have on the work environment, and ways to consider such potential effects.

Brave New World is set in a dystopian future and has been adapted numerous times, most recently into a 2020 TV series. It portrays a dystopic civilization whose members are shaped by genetic engineering and behavioural conditioning. Their happiness is maintained by government-sanctioned drug consumption. It is a world where countries are protected by walls that keep the undesired away — an eerily familiar scenario to Donald Trump’s promise of building a wall on the U.S.-Mexico border.

By reading the novel, business managers can compare the world we live in today and the path our countries and corporations are on to the fictional events in the novel. This can help them pay attention to and address less comfortable, and sometimes often neglected, sensitive workplace issues that need to be considered when planning for the future.

For example, in Brave New World, the consumption of the drug “soma” becomes the norm upon which life is founded. When soma is taken away, individuals can no longer face their reality and they end up welcoming death.

Brave New World offers workplace leaders a look at what could happen if employees’ wellness, mental health or drug use are disregarded, and lead to isolation, absence, resignation or, in dire circumstances, suicide.

To study sensitive workplace issues that could help generate new knowledge, lead to envisioning ways to act appropriately and develop future strategies, business managers can follow these steps:

Reading has surged during lockdown. But literary works can provide us with more than a leisurely pastime. For businesses, novels represent a legitimate way to study the workplace, and this is accomplished by comparing the path our countries and corporations are on today to fictional events.![]()

Nada Elnahla, PhD Candidate, Sprott School of Business, Carleton University and Ruth McKay, Associate Professor, Management and Strategy, Sprott School of Business, Carleton University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Amy Louise Blaney, Keele University

Justice League director Zach Snyder has said he is interested in working on a “faithful retelling” of Arthurian myth. Cut to a small horde of Arthurian scholars (myself included) entering stage left to loudly proclaim that there is no such thing as a “faithful retelling” of the King Arthur myth. King Arthur is one of the most pervasive legends of all time. What scholars call the “Arthurian mythological concept” has developed over several centuries – and over several cultures. Indeed, what makes the Arthur legend so enduring is its very lack of fidelity.

Although many of us today get our first taste of the Arthurian legend from films such as Guy Ritchie’s King Arthur: Legend of the Sword (2017) or TV shows such as the BBC’s Merlin (2008-2012), the core elements of the story that we recognise remain largely medieval.

Arthur’s name first appears in the work of ninth century Welsh historian Nennius. However, the legend as we know it today – knights in shining armour, damsels in distress, Round Table, Holy Grail etc – gallops into view from around the 12th century onward. This heralds the start of what is now known as the “Romance Tradition”.

Chances are that if you’ve read a version of the Arthur story today it is likely to be one of these Romances – most likely Thomas Malory’s 15th-century Morte D’Arthur or an early 20th-century re-telling such as TH White’s The Once and Future King. The tradition also proved very popular with the Victorians – especially with the Pre-Raphaelites, whose visual depictions of Arthurian legend frame the way we see the legend today.

For example, their paintings popularised captivating female figures such as the virginal Maid of Astolat (or Shallot), the dangerous enchantress Morgan Le Fay and the beguiling Lady of the Lake, the temptress Nimue.

One thing that remains consistent throughout the centuries however is the Arthurian myth’s ability to remain relevant to the people, countries, and eras in which it is being retold.

In the late 17th-century, for example, Arthur was enlisted in the wake of the Glorious Revolution of 1688 as a means of bolstering support for the new Protestant regime and their political allies. Physician-poet Richard Blackmore wrote two lengthy epic poems – Prince Arthur (1695) and King Arthur (1697) – comparing the new King William III to Arthur and praising the way in which the monarch’s religious (and, crucially, Protestant) piety would “fresh Life to Albion […] impart”.

This was certainly not the first time Arthur had been associated with the English throne. Both the Tudors and the Stuarts adopted the mythical king to suit their own political purposes, with Henry VII going so far as to repaint the Winchester Round Table with a Tudor Rose at its centre. The paint job was probably in honour of a state visit by the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V in 1522 and – just to ensure that Charles got the message – Henry also had himself depicted on the table, sitting in Arthur’s place.

Nor was it the last time that Arthur would find himself so conscripted. Elements of the Arthurian story – most notably the figure of Merlin – were used in the early 18th-century by the Hanoverian monarchs and their supporters to bolster their own claims to an inherently “British” identity.

Queen Caroline, a clever and well-informed curator of her own public image, capitalised upon the 18th-century’s rediscovery of its national history through ancient heroes. In collaboration with architect William Kent, she developed Merlin’s Cave – a name suggestive of a grotto but in reality more of a thatched folly (a round house with a thatched roof) designed around the Merlin myth – in the gardens at Richmond in 1735.

Numerous panegyric poems – poems designed to publicly praise and flatter – followed including two by “a lady subscribed Melissa”. The first praises “Her Majesty Queen Guardian” as the inheritor of Merlin’s legacy. The second, entitled Merlin’s Prophecy, envisages Frederick, Prince of Wales as “Ordain’d, to wield the Sceptre Royal […] And rule o’er Britons, Brave, and Loyal”.

As these examples illustrate, the one thing we can really say with any certainty about the Arthurian mythos is that fidelity is – as with any myth – an impossible concept.

Arthur has come a long way since his ninth century origins and our modern interpretations show no signs of altering that trend. Whether it’s making us laugh about the airspeed velocity of an unladen swallow in Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975) or putting women centre stage in Cursed (2020), the appeal of Arthur’s mythical world is its adaptability.

He might be “The Once and Future King”, but there’s no such thing as faithful in Arthur’s mythical world.![]()

Amy Louise Blaney, PhD Candidate and Associate Lecturer in English Literature, Keele University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

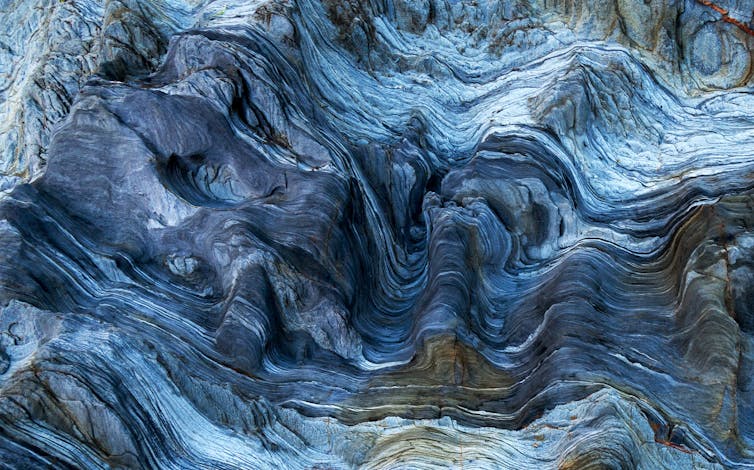

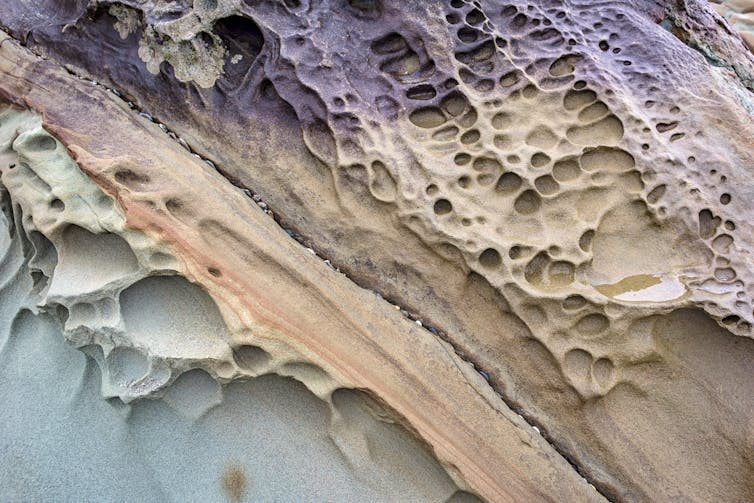

Shutterstock/Francisco Duarte Mendes

Philip Steer, Massey University

Just as writers and artists today are responding to the Anthropocene through climate fiction and eco art, earlier generations chronicled an environmental crisis that presaged humanity’s global impact.

The Anthropocene is a proposed geological epoch that powerfully expresses the planetary scale of the environmental changes wrought by human activity.

Yet almost a century ago, New Zealand and Australia were at the forefront of an environmental crisis that was also profoundly geological in nature: erosion. And it, too, left its mark on culture.

Erosion was first brought to the attention of the western world in the 19th century by the American diplomat and polymath George Perkins Marsh. In Man and Nature: Or, Physical Geography as Modified by Human Action (1869), he argued that much of the “Old World” of the Mediterranean had been transformed into desert by deforestation.

He warned that European colonisation threatened a similar fate for other parts of the world. These concerns came back with a vengeance in the 1930s, when the Dust Bowl in the United States began to raise alarm about the long-term security of global food supply.

In the 1930s, south-eastern Australia was also plagued by dust storms. The biologist Francis Ratcliffe, in Flying Fox and Drifting Sand: The Adventures of a Biologist in Australia (1939), described the situation in South Australia as a fight for survival.

Nothing less than a battlefield, on which man is engaged in a struggle with the remorseless forces of drought, erosion and drift.

In New Zealand’s different climate and topography, another version of the erosion crisis was also becoming evident. Geographer Kenneth Cumberland described the growing desolation of the North Island’s hill-country pasture.

Miles upon miles of the Hawkes Bay, Poverty Bay, Wanganui and Taranaki- Whangamomona inlands have slip-scarred slopes […] The recent history of these regions is one of abandonment, of decreasing population, of a succession of serious floods, and of slip-severed communications.

Cumberland argued in 1944 that New Zealand’s soil erosion problems “attain the extreme national significance […] of those of the United States.”

Similarly, in 1946, the geographer J. M. Holmes claimed:

No greater peace-time issue faces Australia than the conquest of soil erosion.

Because agriculture is so central to western ideas of civilisation, commentators found that cultural and environmental questions were inextricable. This overlapping of science and ideology is evident in G. V. Jacks and R. O. Whyte’s The Rape of the Earth: A World Survey of Soil Erosion (1939), written by two scientists at Oxford’s Imperial Bureau of Soil Science.

The organisation of civilised societies is founded upon the measures taken to wrest control of the soil from wild Nature, and not until complete control has passed into human hands can a stable superstructure of what we call civilisation be erected on the land.

The belief that nature must be subdued and remade was especially potent among the settler populations of Australia and New Zealand. There colonial identity and economic survival were both inextricably bound up with the success of agricultural and pastoral production.

Elyne Mitchell, now best known as the author of the Silver Brumby children’s books, wrote extensively in the 1940s about how cultural norms of white Australians were directly impacting the soil.

To fit Australia into the pattern of Western civilisation, economically and socially, we have upset the natural balance and turned ourselves into destroyers instead of creators.

The cultural commentator Monte Holcroft used even stronger language to express a similar thought in Creative Problems in New Zealand (1948).

But we see also the bare hillsides, the remnants of forest, the flooding rivers, and in some districts the impoverished soil. The balance of nature has changed. Are we to assume that a people which possessed the land in this manner — raping it in the name of progress — can remain untroubled and secure in occupation?

As the title says, erosion was now a “creative problem”. Even as they were committed to colonial forms of society, settler writers were increasingly aware that their environmental foundations were not as stable as had previously been assumed.

In New Zealand literature, the landscape wasn’t simply a backdrop: writers often depicted Pākehā identity as being produced through a direct confrontation with geology. The poet and critic Allen Curnow described the sense “that we are interlopers on an indifferent or hostile scene” as a “common problem of the imagination”. As Curnow wrote in his poem, The Scene, in 1941:

Here among the shaggy mountains cast away

Man’s shape must be recast

Settlement was also described as an encounter between “man” and the landscape in an influential poem by Charles Brasch, The Silent Land, in 1945:

Man must lie with the gaunt hills like a lover,

Earning their intimacy in the calm sigh

Of a century of quiet and assiduity.

Critic Francis Pound has described this nationalist preoccupation as a “soil mysticism”. In focusing so closely on the soil, Pākehā writers were also able to overlook its occupancy by Māori and their own deep knowledge of the land.

Yet Brasch’s appeal is to “gaunt hills”: the landscape of literature was more often than not eroded rather than untouched.

Frank Sargeson’s 1943 short story, Gods Live in Woods, drew on the experience of his uncle, who had felled the forest to establish a hill country farm in Te Rohe Pōtae/the King Country.

And places where the grass still held were scarred by slips that showed up the clay and papa. One of these had come down from above the track, and piled up on it before going down into the creek. A chain or so of fence had been in its way and it had gone too. You could see some posts and wires sticking out of the clay.

Erosion also spread into the common stock of literary imagery. In a short poem by Colin Newbury, In My Country (1955), it appears as a metaphor for disappointed love.

He stands close to the earth,

My obdurate countryman,

Drawing from the wind’s breath,

The arid sweetness of flower and mountain;

Knows no green herb for the heart’s erosion.

Such texts demonstrate the ecological concept of “shifting baseline syndrome”, as described by Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing and her collaborators, whereby “newly shaped and ruined landscapes become the new reality”.

Although so much of Pākehā writing about geology from this time imagines the relationship between humanity and nature as hostile and irreversibly damaged, some offered glimpses of alternative possibilities. One was Ursula Bethell, whose poem Weathered Rocks (1936) stretched her Christian beliefs to find common ground with geology. Through this she imagined a less antagonistic relationship with nature.

And we are kin, compounded of the same elements,

Alike proceeding to an unknown goal.

Another approach is offered by Herbert Guthrie-Smith in Tutira: The Story of a New Zealand Sheep Station (1921). Through the local histories he gleaned from Ngāti Kurumōkihi elders, Guthrie-Smith came to reject a Pākehā view of the Earth as simply a resource to be exploited.

When a block of land passes, as it may do through the hands of ten holders in half a century, how can long views be taken of its rights? Who under these conditions can give his acres their due?

Auē, taukari e, anō te kūware o te Pākehā kāhore nei i whakaaro ki te mauri o te whenua. Alas! Alas! that the Pākehā should so neglect the rights of the land, so forget the traditions of the Māori race, a people who recognised in it something more than the ability to grow meat and wool.

This view of the land as a political partner, endowed with independence and rights, appears to offer a new environmental perspective that in fact draws on the long-standing Indigenous legal principles of tikanga Māori.

Read more:

Dead as the moa: oral traditions show that early Māori recognised extinction

Mid-20th century settler writing about erosion holds renewed interest today because it conveys a strikingly literal, visible sense of the Anthropocene: the geological impact of colonisation was plainly evident in sand drift, dust storms and scarred hillsides.

Writers were not blind to environmental damage, but in the main their responses are reminiscent of what critic Greg Garrard has called the present-day “gloomy trio of Anthropocenic futures — business-as-usual, mitigation and geo-engineering”.

But writers such as Bethell and Guthrie-Smith demonstrate the ongoing importance of creative work for questioning the values that created and sustain the Anthropocene we now all inhabit.![]()

Philip Steer, Senior Lecturer in English, Massey University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that takes a look at writing Dystopian novels during Dystopian times.

For more visit:

https://blog.bookbaby.com/2020/10/writing-dystopian-novels/

The link below is to an article reporting on the longlist for the inaugural ARA Historical Novel Prize.

For more visit:

https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2020/10/07/157667/longlist-announced-for-50000-inaugural-historical-novel-prize/

The link below is to an article reporting on the winner of the 2020 Arthur C. Clarke Award for science fiction, Namwali Serpell for ‘The Old Drift.’

For more visit:

https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2020/10/02/157541/serpell-wins-2020-arthur-c-clarke-award-for-the-old-drift/

Diana Wallace, University of South Wales

Georgette Heyer kept only one fan letter. It was from a Romanian political prisoner who had raised her cell-mates’ spirits over a 12-year incarceration by retelling the story of Heyer’s Friday’s Child.

“Truly,” she wrote, “your characters managed to awaken smiles, even when hearts were heavy, stomachs empty and the future dark indeed!”

In times of stress, many of us crave a little light relief and, ideally, a happy ending. During the second world war, readers turned to historical romance for a past which seemed more colourful than the dreary present of restrictions and rationing. A young war-worker told the Mass Observation organisation, which recorded everyday experience, that she liked “books dealing with some costume period when smugglers had the rule of the seas. I like books to take me into another world far from the realities of this one”.

This is a genre in which women have excelled, particularly in the 20th century. Indeed, by the mid-20th century the historical novel had become so associated with female writers and readers of “costume romance” that the entire genre was dismissed by critics as merely escapist. It was not until the 1990s that historical fiction began to be taken seriously again.

And yet, as is so often the case with genre fiction, historical novelists have used formulaic plots and tropes to disguise controversial material and smuggle it past the censors.

As during the second world war, we are once again facing a period of great upheaval and as such our reading habits have changed to reflect that. A recent survey found that we are reaching for books that offer comfort in their formulaic narratives.

Historical romance allows us a space of relief from present worries but these novels are more than just escapism. While their narrative arcs may be familiar, they also ask still-crucial questions about the politics of gender, sexuality, class and nationhood.

Here are five great examples:

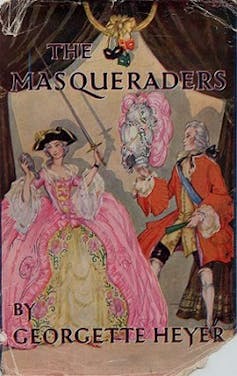

Considered the inventor of the Regency romance, Heyer is admired for her authentic period detail. A superb stylist (she described her prose as a mixture of Jane Austen and Samuel Johnson), she is also a brilliant comic writer. The Masqueraders is one of her most engaging novels, not just for the entanglements that ensue when a brother and sister swap clothes to avoid detection as escaped Jacobites but also because it poses questions about gender identity which resonate today. Reading it you may wonder to what extent is gender a matter of costume, a masquerade which we all perform.

My copy is now yellowed with age but each time I dip into it I am transported to Restoration Cornwall and the lush green-shadowed enchantments of a hidden creek in midsummer where a pirate ship is anchored in secret. Just shy of her 30th birthday, Dona St Columb slips away from her husband and children and dresses as a cabin boy to go adventuring with her French pirate lover. Written during war-time, du Maurier’s novel evokes an imagined past as a space of freedom for women who can escape their restrictive domestic responsibilities only “for a night and for a day”.

For anyone who has more time to read during lockdown, Dunnett’s six-volume series offers the pleasures of a vast historical canvas stretching across sixteenth-century Europe from Scotland to Russia and North Africa. Genre fiction often allows women writers to ventriloquise male characters and Francis Crawford of Lymond, a charismatic but troubled young Scottish nobleman, is a hero of quicksilver complexity and many disguises. As he negotiates the power politics of Europe, particularly the fractious relationship between Scotland and England, Dunnett traces the beginnings of the modern world in the building of nation-states and the development of new art and culture.

In this subversively sexy picaresque novel set in 1890s London, Waters exploited the conventions of historical romance to slip a lesbian love story into the mainstream. Her appealing narrator Nan King is a working-class oyster girl from Whitstable who becomes a music hall “masher” or male impersonator, then a rent boy and finally the kept “tart” of a wealthy socialite before she finds happiness among a group of socialists. Intelligent, witty and stylish, the novel reimagines a lost lesbian history through vivid sensual detail, evocative period slang (the title is a sexual euphemism) and a satisfyingly complex plot.

This was the novel which ignited our current passion for the Tudors and recovered the story of Mary Boleyn, mistress to Henry VIII before her more famous sister Anne married him. With two heroines Gregory can negotiate one of the most tricky elements of historical romance: the fact that with “real” historical figures we already know the ending (and who doesn’t know that Anne Boleyn had her head cut off?). The heart of this often contentious novel is the relationship between the two sisters as they choose different ways to negotiate the dangers of the Tudor court and decide whether to marry for ambition or love.![]()

Diana Wallace, Professor of English LIterature, University of South Wales

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.