The link below is to an article that lists the 100 notable books of 2018 according to The New York Times.

For more visit:

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/11/19/books/review/100-notable-books.html

The link below is to an article that lists the 100 notable books of 2018 according to The New York Times.

For more visit:

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/11/19/books/review/100-notable-books.html

Viacheslav Nikolaenko via Shutterstock

Sara Haslam, The Open University; Edmund King, The Open University, and Siobhan Campbell, The Open University

Bibliotherapy – the idea that reading can have a beneficial effect on mental health – has undergone a resurgence. There is mounting clinical evidence that reading can, for example, help people overcome loneliness and social exclusion. One scheme in Coventry allows health professionals to prescribe books to their patients from a list drawn up by mental health experts.

Even as public library services across Britain are cut back, the healing potential of books is increasingly recognised.

The idea of the healing book has a long history. Key concepts were forged in the crucible of World War I, as nurses, doctors and volunteer librarians grappled with treating soldiers’ minds as well as bodies. The word “bibliotherapy” itself was coined in 1914, by American author and minister Samuel McChord Crothers. Helen Mary Gaskell (1853-1940), a pioneer of “literary caregiving”, wrote about the beginnings of her war library in 1918:

Surely many of us lay awake the night after the declaration of War, debating … how best we could help in the coming struggle … Into the mind of the writer came, like a flash, the necessity of providing literature for the sick and wounded.

The well-connected Gaskell took her idea to the medical and governmental authorities, gaining official approval. Lady Battersea, a close friend, offered her a Marble Arch mansion to store donated books, and The Times carried multiple successful public appeals. As Gaskell wrote:

What was our astonishment when not only parcels and boxes, but whole libraries poured in. Day after day vans stood unloading at the door.

Gaskell’s library was affiliated to the Red Cross in 1915 and operated internationally – with depots in Egypt, Malta, and Salonika. Her operating principles, axiomatic to bibliotherapy, were to provide a “flow of comfort” based on a “personal touch”. Gaskell explained that “the man who gets the books he needs is the man who really benefits from our library, physically and mentally”.

Her colleagues running Endell Street Military Hospital’s library shared similar views about the importance of books in wartime. On August 12, 1916, the Daily Telegraph reported on the hospital, calling the library a “story in itself”. Run by novelist Beatrice Harraden, a member of the Womens Social and Political Union and also, briefly, the actress and feminist playwright Elizabeth Robins, the library was a fundamental part of the treatment of 26,000 wounded between 1915 and 1918.

“We learned,” Robins wrote in Ancilla’s Share, her 1924 analysis of gender politics, “that the best way, often the only way, to get on with curing men’s bodies was to do something for their minds.”

The books the men wanted first were likely to be by the ex-journalist and popular writer Nat Gould, whose novels about horseracing were bestsellers. Otherwise, fiction by Rudyard Kipling, Marie Corelli, or Robert Louis Stevenson rated highly. In the Cornhill Magazine in November, 1916, Harraden revealed that the librarians’ “pilgrimages” from one bedside to another ensured what she called “good literature” was always within reach, but that the book that would “heal” was the one that was most wanted:

However ill [a patient] was, however suffering and broken, the name of Nat Gould would always bring a smile to his face.

The literary caregivers at Endell Street worked responsively, and without judgement, a crucial legacy.

Literary caregiving also took place closer to the front. Throughout the war, the YMCA operated a network of recreation huts and lending libraries for soldiers. After losing his only son, Oscar, at Ypres, the author E. W. Hornung offered his services to the YMCA. Hornung – a relatively obscure figure now, but a literary celebrity then – authored the “Raffles” stories about the gentleman thief of the same name.

Arriving in France in late 1917, Hornung was initially put to work serving tea to British soldiers. But the YMCA soon found him a more suitable job, placing him in charge of a new lending library for soldiers in Arras. Dispensing tea and books to soldiers helped him process his grief. Hearing soldiers talk about their favourite books played a key role in his recovery – but he also sincerely believed that reading helped soldiers keep their minds healthy while they were in the trenches. Hornung wrote in 1918 that he wanted to feed “the intellectually starved”, while “always remembering that they are fighting-men first and foremost, and prescribing for them both as such and as the men they used to be”.

Present-day veterans encounter the potential of reading and writing in equally participatory ways as interventions with the charities Combat Stress UK (CSUK) and Veterans’ Outreach Services demonstrate.

In CSUK, we read widely from contemporary work before undertaking writing exercises. These were designed to help provide detachment from the internal repetition of traumatic stories that some with PTSD experience. The director of therapy at CSUK, Janice Lobban, says:

Collaborative work … gave combat stress veterans the valuable opportunity of developing creative writing skills. Typically, the clinical presentation of veterans causes them to avoid unfamiliar situations and the loss of self-confidence can affect the ability to develop creative potential. Workshops within the safety of our Surrey treatment centre enabled veterans to have the confidence to experiment with new ideas.

Another approach, in workshops with Veterans’ Outreach Support in Portsmouth in 2018, explored the role of writing in training veterans to become “peer-mentors” of other veterans wanting to access VOS services, ranging from physical and mental wellness to housing benefits to job-seeking.

The results show that veterans responded positively to opportunities for imaginative writing. Trainee peer-mentors responding to a questionnaire told us that the exercises helped them to write fluently about their own lives. For people who spend so much time filling out forms to access various benefits, the opportunity to write creatively was seen as a liberating experience. As one veteran put it: “We are writing into ourselves”.

For 100 years now, reading and writing have helped veterans build relationships, gain confidence and face the challenges of their post-service lives. Our current research charts the influence of wartime literary caregiving on contemporary practice.![]()

Sara Haslam, Senior Lecturer in English, The Open University; Edmund King, Lecturer in English, The Open University, and Siobhan Campbell, Lecturer of Creative Writing, The Open University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Shutterstock

About 15 years ago I was in a Minneapolis conference centre, about to deliver a paper on elephants in Southern African fiction, when I encountered a curious local in an elevator. When I told her that one of my subjects was Wilbur Smith’s thriller, Elephant Song, she enthused,

Oh, I just loved that book; I contribute every year now to the Hohenwald Elephant Sanctuary.

I didn’t tell her that my paper critiqued the novel for being exploitative, and grossly sensationalist. Despite its title, the book is only tangentially interested in elephants – at least in comparison with Dalene Matthee’s famous Circles in a Forest, perhaps South Africa’s most eco-sensitive novel ever.

There’s no telling what people will get out of their reading. Even in our era of super-saturating graphics and television, photography and film, literature still has a considerable effect on public perceptions of environmental issues. Until very recently, of course, reading was the primary mode of information transfer. Many attitudes towards, say, elephants were established through literature, and persist in other media today.

This is the purview of my new book, Death and Compassion: The elephant in Southern African Literature. The book takes the region south of the Zambezi as its stamping-ground. It explores how various genres of literature reflect attitudes towards elephants. It takes literature in a broad sense, probing beyond the standard fiction and poetry into non-fiction forms such as hunting accounts and game-ranger memoirs.

Each chapter asks questions crucial to our understanding of our place in the natural world. It does so conscious that this understanding is the great problem of our times, superseding and enveloping all more localised and political squabbles. What is the relationship between science and compassion? Why do men hunt? How do we educate the young about animals, the environment and us? What sense of “community” might include wild and even dangerous animals?

Elephants raise the conflicting emotions involved in humanity’s ongoing struggle to balance exploitation and well-being, damage and compassion to a particularly intense pitch.

Can we look to indigenous cultures for guidance, as conveyed by rock art, folktales and proverbs? The rock art is relatively opaque, while oral productions are now so refracted through translation into modern literary media that it’s hard to be sure what the originals’ attitudes towards elephants might have been. Reverence, awe, and taboo are evident enough, but it seems that animal compassion is an invention of modernity.

Compassion, at least as it emerges in this literature, seems to develop in response to destruction. It strengthens belatedly but proportionately to the catastrophic decimation of wildlife under invading white firepower, and the consequent sense of loss. I found the chapters on the 18th Century travel accounts (from Pieter Kolbe through François Le Vaillant to John Barrow), and the later nineteenth-century hunting accounts (from Roualeyn George Gordon-Cumming to Frederick Courteney Selous) the hardest to write.

The unremitting slaughter related by these adventurers is stomach-turning to say the least. Not that the hunters were oblivious to an ethical issue: without exception they engage at some level with already-nascent arguments for compassion.

Without exception they find literary methods to evade or suppress any emotions which impede the drive to kill. The genre is distinguished by its evasive manoeuvres designed to avoid thinking about it at all.

The adult fictions, from H. Rider Haggard to Wilbur Smith, are little better, being largely gratuitously gory adventure-tales which come to centre repetitively on a duel-like situation: single hunter versus great old tusker. It seldom ends well for the elephant.

Still, a shift becomes discernible in mid twentieth-century novels. “Conservation” is gaining traction, so the novel, just as it had migrated out of the hunting account, now drifts into some commonalities with the modern game-ranger memoir. The ranger becomes the hero, saving the tusker from poachers.

Of course, shadowing all this is the ivory trade. It had existed for centuries, drove most of the early slaughter and drives the renewed slaughter today. In some estimates, an African elephant is being killed every 15 minutes.

Ironically, because of the colonial-era establishment of game reserves like Kruger, southern Africa’s elephants so flourished that that other side of slaughter – the organised “cull” – for a time became the management tool of choice. The ethics of culling preoccupy both late novels and memoirs by rangers, scientists and managers (such as Caitlin McConnell and Lawrence Anthony).

In most recent works, the relatively new perception of elephants not just as mobile repositories of ivory but as emotionally sensitive, uniquely communicative and socially complex – almost human, even a model for humans – achieves unprecedented prominence.

This is especially so in fiction for children, in which compassion and empathy seem more acceptable, as if they are merely childish motivations for action in the world. A disastrous stance.

Poachers and ivory traders are unlikely to be persuaded by literature. Nevertheless, understanding stories – those of the murderous as well as of the compassionate – is vital to generating the critical mass necessary to save natural environments and their multiple denizens, from elephants to herons, from octopi to ants – and ourselves – from the myopia of Mammon.

Compassion alone, unanchored by economic and legislative power, is unlikely to reverse the tide of environmental destruction, but without cross-species compassion, we are surely lost.

Death & Compassion: The elephant in Southern African Literature is published by Wits University Press![]()

Dan Wylie, Professor of English, Rhodes University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Martin Goodman, University of Hull

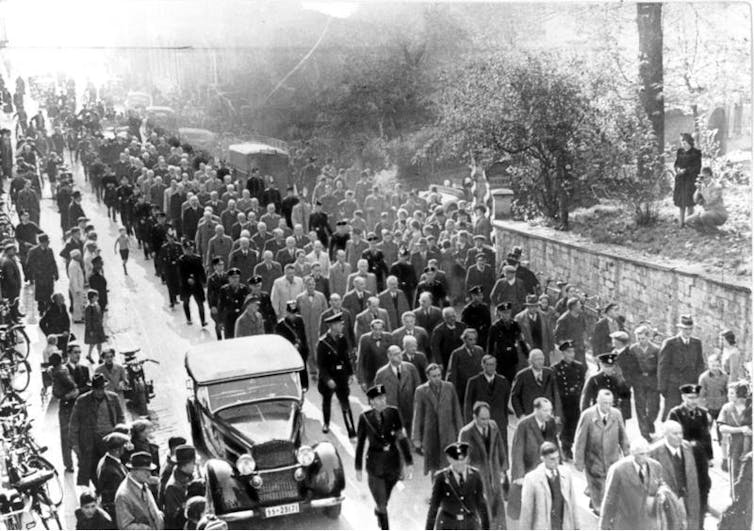

On the evening of November 9 1938 a Nazi pogrom raged across German and Austrian cities. Nazis branded the atrocity with a poetic term: Kristallnacht or “Crystal Night”. In that branding, fiction took hold. In English it translates as “The Night of Broken Glass” but that also tames the horror. Yes, broken glass from Jewish shopfront windows littered the streets, but also hundreds of synagogues and Jewish businesses were burned to the ground while Jews were beaten, imprisoned and killed.

Eight decades later, novelists are still trying to make sense of the pogrom – which was was designed to give the Nazi Party’s antisemitic agenda the legitimacy of public support.

Kristallnacht marked a new epoch. Earlier pogroms, such as in Russia, were popular riots – now, for the first time, an industrial nation turned the forces of the state against an ethnic group within its own borders. To get away with this, a state needs to control the narrative. In this instance, propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels was the key player. When a young Polish Jew named Herschel Grynszpan entered the German Embassy in Paris and shot a German official, Goebbels saw the possibilities. He used news of the event to trigger Kristallnacht.

The state that attacks its citizens also turns on its writers and free-thinkers – people who can construct a counter-narrative. The future Nobel Prize-winner Elias Canetti and his wife, the writer Veza, were such people. “We shall remember this November”, a Jewish character reflects in Veza Canetti’s novel The Tortoises, “when we are all being punished because a child went wrong and was led astray”.

In the wake of Kristallnacht, the Canettis fled Vienna for Paris and by January 1939 had settled in exile in London, where, in a feverish three months, Veza wrote her novel (unpublished until this century). It provides a window on how intellectuals fought to understand the unimaginable as it unfolded. “The temples are burning!” says one character. “Can you believe that’s possible?” asks another. So why don’t they go and see for themselves? “People haven’t the heart. They feel like criminals. They believe the temple will strike them down if they watch and don’t do anything about it.”

Emil and Karl, the first published novel to feature the pogrom, came out in New York in February 1940. Yankev Glatshteyn, a Polish Jew and immigrant to the US, wrote it in Yiddish to alert American Jewish youngsters to the perils facing their European kindred. It features two friends, one a Jewish boy and the other the son of socialists. Forced to scrub streets clean with their hands after Kristallnacht, both boys learn they must flee their country if they are to stay alive.

Christa Wolf, who forged life as a writer in what became East Germany, fed her memories of the night into Nelly, a character in her 1976 novel A Model Childhood. Nelly knew nothing of Jews, but in that pogrom she witnessed a burning synagogue. “It wouldn’t have taken much for Nelly to have succumbed to an improper emotion: compassion,” Wolf reflected. “But healthy German common sense built a barrier against it: fear.” These asides of bitter irony note the chilling reality of the time: those who showed sympathy for the plight of the Jews risked sharing their plight.

So to the 21st century. With events such as Kristallnacht locked away in history, what use are we novelists? Novels unlock history. Governments maintain their hold on narratives that justify abuses of power – but novelists can invert that narrative order to reveal neglected viewpoints.

In 2009, Laurent Binet novelised the life and death of Reinhard Heydrich (a man known as “Hitler’s Brain” – the German acronym which gives the book its title: HHhH. Under orders from Goebbels, Heydrich set the November pogrom in motion. Binet maintains clinical control of the story, anchoring it to archived fact. Heydrich is shown measuring Kristallnacht’s efficiency, including the cost of all the broken glass.

In Michele Zackheim’s Last Train to Paris (2013) an American Jewish female journalist is dispatched into Nazi-controlled Berlin. Highlighted here is not the broken glass, but the fires.

[With] no wind, clouds of smoke were perched on top of each burning building. In between the buildings, perversely, as if Mother Nature were laughing at our idiocy, we could see the stars.

Those fires also burn a synagogue in a remote Austrian town in The Lost Letter, the 2017 novel by Jillian Cantor – a novelist who focuses on 20th-century history. Cantor’s novel follows Zackheim’s in looking back over decades, seeking emotional engagement with distant tragedy.

Günter Grass was ten on Kristallnacht, the same age as Oskar in his novel The Tin Drum (1952). The Jewish toyshop that supplied Oskar’s drum was burned down that night and the shop owner killed himself – “he took along with him all the toys in the world”. A character akin to Grass appears in John Boyne’s 2018 novel A Ladder to the Sky. In his teens Grass joined the Waffen-SS – a fact he kept secret until old age.

In Boyne’s book, the central character, a writer, took actions after Kristallnacht that destroyed a Jewish family. Like Grass he contained the story for decades. Of course, the true storyteller must share and not conceal stories. Wolf showed us how fear was a barrier against compassion. Boyne makes us face the consequences of overcoming such fear.

Once people would have said Kristallnacht was unimaginable in a modern context. But they were wrong – do Roma feel safe from the actions of the Hungarian State today? How safe are the Rohingya in Myanmar, Mexicans in the US, the Windrush generation in the UK?

Through fiction we can enter history, encounter suffering and exercise compassion. We close our book, awakened. Fiction sharpens memory for when history repeats itself.![]()

Martin Goodman, Professor of Creative Writing, University of Hull

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Archie Dick, University of Pretoria

On the advice of the State Librarian one fine day in the 1970s, a truck transported thousands of books and magazines from Pretoria’s Central Police Station to a dark hall at the Iscor state steel company, just outside the South African capital. A large mechanical shovel scooped up and dropped them into a 20 metre high oven, causing it to spew flames and smoke. This was another truckload of material that had been banned for political reasons and was routinely burned in furnaces across South Africa from the 1950s to the 1970s.

Historical examples show that books are banned and destroyed because they offend the politics, morals, or religion of the day. Information science academic Rebecca Knuth, wrote in Burning Books and Leveling Libraries that if a regime is racist, it destroys the books of groups deemed inferior; if nationalistic, the books of competing nations and cultures; and if religiously extremist, all texts contradicting sacred doctrines.

Sometimes these forces combine. Recent examples include the destruction of Muslim books and libraries in Bosnia in the 1990s by

Serbian nationalist forces. In 2013 there was the burning by Islamist insurgents of the Timbuktu library and the next year the same happened in Lebanon to Tripoli’s historic Al Sa’eh Library.

The apartheid era – from the middle of the 20th century – had its own variation on the theme. Thousands of books were banned, ranging from Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s The Insulted and Humiliated to popular Westerns writer Louis L’Amour’s Hopalong Cassidy series.

The fact that books were burnt underscored the state’s desire to make sure the printed word was utterly destroyed. The practice also revealed a darker side of the library profession which connived in the book burning. Between 1955 and 1971 most librarians didn’t protest when thousands of books and other reading material were taken from libraries, and burned at municipal incinerators and furnaces. Some even joined in.

State sanctioned book burnings were common as authoritarianism accompanied a growing Afrikanerisation of South African society as the dominant, ruling Afrikaner elite started to impose its culture on all spheres of society. Members of the elite did this first by unifying Afrikaner cultural and church organisations. This took the form of a declaration on behalf of “Volksorganisasies” (Afrikaner people’s organisations) that was signed in 1941 and pledged support for conservative Christian national ideology.

This sometimes involved the burning of books as a symbol of purification. One of the more worrying aspects was the solid support from ordinary South African librarians for these treacherous acts.

Even when books were burned by public libraries, the profession meekly accepted the situation. This signified support and agreement with what was happening, and reflected the dominant authoritarian mood and spirit in South Africa and the library community at that time.

In October 1955, the city librarian of Johannesburg, exclaimed:

All copies are brought in to me and I destroy them personally.

In the same month, a Cape Town newspaper reported that a couple of hundred books had been burned. Two years later, the deputy city librarian of Cape Town announced the fate of banned books returned from branch libraries to his Central Library:

We will have a big bonfire and burn them.

What started as the burning largely of imported pornographic books, became an all-out attack on free speech after the findings of a commission of inquiry into “undesirable publications” were made public in October 1957. The inquiry gave the Nationalist government the excuse to destroy books and pamphlets critical of its policies, and of dramatic developments in the country.

Each new issue of the Government Gazette included the latest additions to the list of banned books. Books on communism and those that criticised apartheid dogma were targeted. In 1954 banned titles included the Pravda and Daily Worker newspapers, and Vladimir Lenin’s Two Tactics of Social-Democracy in the Democratic Revolution. Books on innocuous topics about communist countries, like China’s “Railways and Labour Insurance Regulations of the People’s Republic of China”, were also deemed subversive and added to the list.

Even Ray Bradbury’s dystopian novel Fahrenheit 451 (which, ironically, is the temperature at which book paper starts burning) was burned. From the town of Brakpan in the North to Durban in the East and Cape Town in the South, several thousands of books were removed from library shelves and burned. In July 1964 Cape Town City library services announced that more than 800 books had been burned.

By this time the list of banned publications had swelled to a total of 12 000 titles. In June 1968, a newspaper reported that 5 375 books of the Natal Provincial libraries had been withdrawn from circulation and burned. By April 1971 books were still steadily being burned in Cape Town – at the rate of two per day.

It was only in the late 1980s that successful appeals from a few brave librarians to the state censors saw restricted books unbanned, and saved from apartheid’s furnaces.

In the early-1990s as South Africa moved towards becoming a democracy hundreds of archival documents and public records were shredded and burned by the apartheid state’s security establishment – once again in the furnaces of Iscor.

Could book burning happen again in contemporary South Africa? Given a similar set of circumstances, there is every reason to believe that it can. South Africans should remain diligent and alert to threats to freedom of expression.

The ashes of burnt books tell of the barbarism to which a society can descend.![]()

Archie Dick, Head of Department and Professor of Information Science, University of Pretoria

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that looks at a new study that confirms growing up in a home full of books is good for you.

For more visit:

http://mentalfloss.com/article/559956/new-study-confirms-growing-home-filled-books-good-you

Kamilla Elliott, Lancaster University

There have been several attempts over the years to make a movie out of DM Thomas’s critically acclaimed 1981 novel, The White Hotel. But despite the involvement of such giants of the screen as David Lynch, Bernardo Bertolucci, Terrence Malik and David Cronenberg – who made a name for himself as a director who can adapt so-called “unfilmable books” – the novel has this far proved resistant to film adaptation.

In the absence of a film version, the book was recently adapted for radio by the BBC, directed by Jon Amiel and based on a screenplay written by the late Dennis Potter in the 1980s.

DM Thomas himself wrote in 2004 about the tortuous and sometimes tortured battle over screen rights for his novel, but apart from the saga over rights – so familiar to any novelist whose work has pricked the attention of film-makers – what was it about the book itself that meant a radio adaptation succeeded when film adaptations have failed?

There are a number of media, cultural and economic conventions that can explain this. But, in general, books that have been called “unfilmable” are books that are hard to read: weighty, ponderous, abstract, complex, convoluted, labyrinthine, densely allusive and excessively long. Or books that treat terrifying, horrifying, revolting or repulsive subjects.

The White Hotel is a difficult read – for a start there’s the unreliable, psychologically disturbed, potentially hallucinating narrator, whose obscene and surreal narratives are followed by representations of horrific historical events and natural disasters. The book’s sections shift jarringly across textual forms and styles – rational, psychoanalytic case notes melt into mythological explorations of psychological symbols. Stories of strange mental states jolt into collective, realist histories. It’s a challenging read.

By contrast, mainstream film conventions require a clear narrative structure and a degree of temporo-spatial logic and continuity. They tend not to favour excessively “talky” screenplays, preferring to tell their stories through visuals and structure them via editing.

These and other reasons that books have been considered unfilmable have been widely discussed. They include historical sprawl (Gabriel Garciá Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude), multiple worlds (Stephen King’s Dark Tower series), too many characters (David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest), and multiple unreliable narrators who confuse the story (Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves).

Some novels are written with a stream of consciousness that keeps the story inside a character’s head (James Joyce’s Ulysses and Thomas Bernhard’s Woodcutters); there may be lack of clear plot and dynamic action (Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse), fantasies too elusive for film’s special effects (H.P. Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness), or a book may be too distressing or obscene to visualise realistically (Art Spiegelman’s Maus and The White Hotel).

Censorship has also limited the number and scope of books that are allowed to be filmed – as films are more tightly controlled and censored than books. The reasons for this tighter control of visual images have ancient roots in Judaic, Islamic and Protestant Christian religions which represent the word as divine and the visual image as profane.

Their legacy persists in secular censorship practices. The US Motion Picture Production Code (MPCC) of 1930 ruled that: “The latitude given to film material cannot … be as wide as the latitude given to book material,” because “a book reaches the mind through words merely; a film reaches the eyes and ears through the reproduction of actual events”. It concluded that:

The mobility, popularity, accessibility, emotional appeal, vividness, straightforward presentation of fact in the films makes for intimate contact on a larger audience and greater emotional appeal. Hence the larger moral responsibilities of the motion pictures.

The MPCC advocated censoring films more stringently than books because film “reaches every class of society”, while other arts have their “grades for different classes”.

Even following the relaxation of the MPPC and similar censorship laws in other nations in the late 20th century, these considerations persist. When James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) was made into a film by Joseph Strick in 1967, it remained banned in Ireland until 2000, whereas the book was never officially banned in Ireland.

When David Cronenberg filmed William S. Burroughs’s so-called unfilmable Naked Lunch (1959) in 1991, and was criticised for not being faithful to the book, he retorted that a “straightforward adaptation”, featuring all of the book’s far-flung locations and representing its most shocking scatological and sexual passages would “cost US$100m and be banned in every country in the world”. So the book could be filmed, but it could not be financed or pass film censorship laws.

Financing and censorship are interconnected: films have to reach a much larger audience than novels or radio plays to turn a profit, and must therefore appeal to the mainstream. BBC Radio 4 has a much smaller audience and can appeal to other demographics on other radio channels.

For all of these reasons, a word-only adaptation for the niche audience of BBC Radio 4, aired on a Saturday afternoon – a time when listener numbers are close to being the lowest of the week – clearly offered an economically viable and socially acceptable venue for transmitting this brilliant and challenging novel in another media form. For this, at least, we must be grateful.![]()

Kamilla Elliott, Professor of Literature and Media, Lancaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that takes a look at the length of books/ebooks – are books/ebooks getting longer?

For more visit:

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/sep/21/the-guardian-view-on-lengthening-books-read-them-and-weep

The link below is to an article that looks at packing books for vacation.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2018/09/21/how-to-pack-books-for-vacation/

Andrew Biswell, Manchester Metropolitan University

The publication of The Fall of Gondolin by JRR Tolkien completes a publishing project that began in the distant past of 1977, when Christopher Tolkien edited The Silmarillion, the first volume of his father’s posthumous stories.

When Tolkien senior died in 1973, he left four full length published novels and a mass of uncollected papers behind him. His youngest son Christopher, now aged 93, has spent almost half a lifetime annotating his father’s work and preparing it for publication. The 12 volumes of the History of Middle-earth provide an astonishingly detailed account of the languages and landscapes of Tolkien’s fictional world.

This monument of scholarship allows readers of The Lord of the Rings to gain the fullest possible understanding of the careful preparation which stood behind the handful of books published by Tolkien in his lifetime.

As a literary critic who specialises in archival work, I admire the heroic labours of the Tolkien estate in presenting the author’s private papers, letters and illustrations to a wide readership of scholars and enthusiasts. But not all heirs and executors take the same view when it comes to publishing posthumous work, and there are often ethical problems arising from an author’s drafts and manuscripts.

When the first edition of Philip Larkin’s posthumous Collected Poems appeared in 1988, many readers were dismayed to find that the editor had chosen to include a large number of unfinished poems and apprentice work written when Larkin was a student. Critics of that volume argued that Larkin would never have allowed publication of this inferior work, and the overall effect was to diminish the impact of the poems he valued.

Publication of the Collected Poems was followed in 1992 by a volume of Larkin’s letters (heavily cut to remove libels), which revealed the poet to have been seething with racist prejudices. It took many years for Larkin’s reputation to recover from these deep wounds, which had been administered by his own literary executors. There will be no posthumous edition of Larkin’s diaries, which were shredded shortly after his death, according to his own instructions.

Read more:

After years of scandal, Philip Larkin finally has a spot in Poets’ Corner

Virginia Woolf’s letters and journals offer a positive counter example. Edited by her nephew Quentin Bell and published posthumously, Woolf’s Diaries have established themselves as an inspiring series of books for everyone who studies her novels. The pleasure of watching over Woolf’s shoulder as she documents the ups and downs of her writing life is immense.

Other writers have attempted to take control of their reputations more directly. W.H. Auden, who died in 1973, stipulated in his will that no edition of his letters should be published, and he requested that anyone who had letters in their possession should burn them. Fortunately for posterity, many of his friends had already sold their batches of Auden letters to university archives, and other people simply ignored his wishes. Nevertheless, it is unlikely that an edited collection of Auden’s letters will ever appear.

Edward Mendelson, who is Auden’s literary executor, recently wrote an article in which he discussed his own ethical dilemmas as the editor of the Collected Poems. Mendelson’s guiding principle has been to value the poems that Auden chose to include in his two volumes of Collected Longer Poems and Collected Shorter Poems.

But what to do about the poems published in magazines but excluded from Auden’s books? Those appear in the Collected Poems on the grounds that Auden had signed them off for publication. And what about the rejected early work, such as the poem “Spain” – a response to the Spanish Civil War published in pamphlet form but later excluded from the Collected Shorter Poems? That does appear in The English Auden, an edition of poems written in the 1930s, but it is absent from the Collected Poems.

There is another category of “lost” work by Auden, existing only in manuscripts and notebooks, but never collected in book form. Mendelson has recently unveiled his plans to publish some of these poems, carefully edited and contextualised, in a volume of Auden’s “Personal Writing”, which will include poems and verse-letters written for friends. But none of this work will be finding its way into the next edition of the Collected Poems.

Anyone who manages a literary estate faces hard questions about what should or should not be published. In September 2018 Manchester University Press will publish Paul Wake’s edition of Puma, a science fiction novel by Anthony Burgess. The manuscript, completed in 1976, was unpublished in Burgess’s lifetime, but letters in the archive confirm that he was actively seeking to find a publisher shortly after he’d written it. What readers will make of this “lost” novel by Burgess remains to be seen.

The Tolkien example is a story of a son’s devotion to his father’s work and there is much to admire in Christopher Tolkien’s determination to put as much unpublished writing as possible into the public domain.

For the future, as electronic communication becomes more pervasive, it seems likely that writers will find it harder to delete published work from the record, or to edit their past in the ways evidenced by Auden and Larkin. If only they had survived into the age of social media, their Collected Tweets might have been required reading for every diligent student of their poems.![]()

Andrew Biswell, Professor of Modern Literature, Manchester Metropolitan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.