Leigh WIlson, University of Westminster

In the literary world and among those for whom fiction is an interest beyond simply reading books, a great deal of attention will be given to the winner of 2018’s Man Booker Prize, Milkman, by Anna Burns. The chair of the judges, philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah, said Burns’ novel, about a young woman being sexually harassed by a menacing older man and set in Northern Ireland, “is a story of brutality, sexual encroachment and resistance threaded with mordant humour”.

Of course, each year, following the announcement of the longlist in July, the shortlist in September and finally the winner in October, a discussion takes place as to what each announcement might mean. As the Man Booker is the most prestigious, remunerative and talked about literary prize in the UK, this “what does it mean?” can be made to reach into just about every crevice of contemporary culture.

Frank Augstein/PA

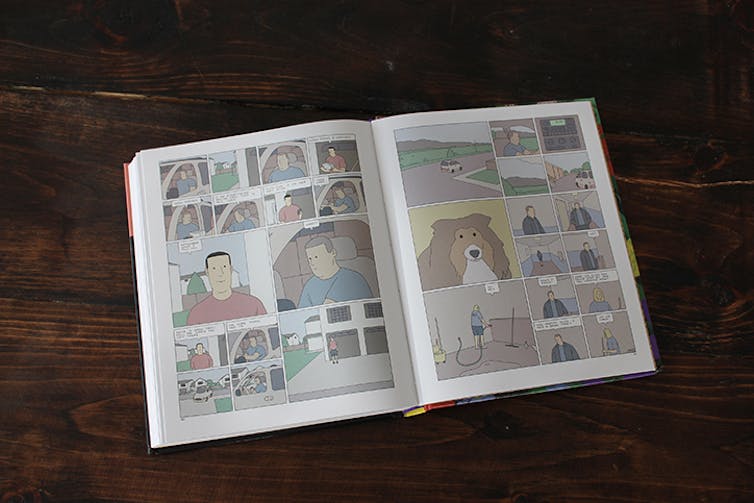

This year has been no exception – discussion of the longlist was dominated by the inclusion of a graphic novel, Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina, and discussion of the shortlist by the presence or absence of millennial writers. Discussion of Milkman will no doubt be dominated by the history of Northern Ireland, by #MeToo and by the fact that Burns is the first UK-born winner for six years.

In these accounts, the significance of the prize is restricted to thinking about those novels that reach the long or shortlist or the one that is declared the final winner. But a range of work from various wings of literary studies over the past few years can help us to answer the question of what winning means in other, perhaps more challenging, ways.

1. It’s a competition

The underlying claim of James F. English’s pioneering 2009 work in the sociology of literature, The Economy of Prestige: Prizes, Awards and the Circulation of Cultural Value, is that both the power of and the problem with prizes consists in the way they equate “the artist with the boxer or discus thrower”. Prizes are competitions.

But while the publicity might go to the winning writers, the real winners are the publishers, who need not just the increased sales and chances of film and TV adaptations that are likely to follow, but also the less tangible boost to their authority and prestige given by a prize. The real winners are also more likely to be not just any publishers, but those that have already been successful. As the novelist Joanna Walsh, among others, has noted, the Man Booker rules make submissions from small publishers very tricky because of the size of the print run required and the amount of money that involves. Because of this, a win can be a drain rather than a boost, and costs can outstrip sales if you don’t win.

2. A competition that maintains a monopoly

It’s not just that the competition is hard for small presses to enter – the big publishers have an near monopoly. In the 50 years that the prize has existed, literary publishing in English has been transformed from being made up of numerous independent companies, often family run, to being almost entirely dominated by the “big five”. These are Penguin Random House, Hachette, HarperCollins, Macmillan and Simon & Schuster. And, further, each of these is itself owned by a multinational media conglomerate.

As the sociologist John Thompson noted in his book, Merchants of Culture: The Publishing Business in the Twenty-First Century, the economies of scale made possible through mergers and acquisitions have created this almost complete monopoly. But through publishing via supposedly “separate” imprints, the big five have maintained an aura of smallness which is more conducive to the “creativity” on which their profits are ostensibly based.

Over the past 20 years, while 12 different publishers appear to have published the novels which were awarded the Prize, six of these wins were for imprints belonging to Penguin Random House. This monopoly is maintained through the prize’s rules for submissions – the number of novels a publisher can submit is directly tied to the number of longlisted novels they have had over the past few years. An imprint already marked as prestigious is more likely to win again.

3. It maintains a certain model of publishing

In his article about Amazon and its relation to contemporary literary fiction, US literary scholar Mark McGurl suggests the extent to which reading of material normally scorned by the literary critic can deliver new insights.

And close reading of the Man Booker’s rules of eligibility – while perhaps dry in comparison to reading the winner on the bus or with a reading group – is also revealing. It shows that it is not just a competition for a small number of large publishers, but that the prize is largely about the maintenance of a certain idea of publishing, too.

The rules of eligibility are almost entirely now about the publisher, rather than the novel or novelist – and key to them is the exclusion of anything with a whiff of self-publishing about it. In order to be eligible, a publisher has to prove that they are based in the UK or Ireland, but the only way of proving this is by having the accoutrements of the conventional publisher. Eligible submissions must come from publishers with ISBNs and head offices who use retail outlets for print books and who publish at least two literary novels a year. Rule 1g, through its strange, uncomfortable tautology, betrays something of just what is at stake in this: “Self-published novels are not eligible where the author is the publisher.”

What the various methods of literary studies can suggest, then, is that, contrary to nearly everything written elsewhere about the Man Booker Prize, it arguably doesn’t really matter which novel wins. Whichever wins, I’d suggest that the real winner is an intensely conventional notion of publishing. It’s an idea of publishing where sales and prestige are the most important consequences of winning prizes and where a few very large publishers dominate.

And, to continue that domination, the most novel uses of contemporary technology, which can open up spaces for the most innovative aesthetic forms become illegitimate. If you want to see examples of this kind of work, look to the recently published novel, Gaudy Bauble, by Isabel Waidner (published by Dostoyevsky Wannabe) – a book of experimental writing published in an innovative way. Under the current rules, such novels could never gain the coverage and attention offered by the Booker. And that’s a great pity.![]()

Leigh WIlson, Professor of English Literature, University of Westminster

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.