The link below is to an article that reports on the winners of the 2021 Western Australia’s Premier’s Awards.

For more visit:

https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2021/08/26/192143/wa-premiers-book-awards-announced/

The link below is to an article that reports on the winners of the 2021 Western Australia’s Premier’s Awards.

For more visit:

https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2021/08/26/192143/wa-premiers-book-awards-announced/

Blair Williams, Australian National University

This week, a new Australian political biography will appear on bookshelves. This is The Accidental Prime Minister, an examination of Scott Morrison by journalist Annika Smethurst.

While a prime minister makes for an obvious – and worthy — biographical subject, it also continues Australia’s strong tradition of focusing on the stories of men in politics.

History as a discipline may have been grappling with gender issues since the 1970s, but political history has been especially resistant to questions about women and gender.

In a recent study for the Australian Journal of Biography and History, I looked at Australian political biographies over the past decade. I found female political figures are almost always ignored.

Political biographies add life, colour and depth to historical events and personalities. They can shape the legacies of politicians long after they’ve left politics. They also show us who is worthy of being written about and who is overlooked in the pages of history.

However, most Australian political biographies have been written about men, particularly male prime ministers.

This inevitably calls to mind the enduring myth of the “Great Man” as the architect of historical change. This is best described by 19th century historian Thomas Carlyle, who believed “the history of the world is but the biography of great men”.

As women were largely excluded from politics until the end of the 20th century, it could be argued they simply haven’t had the opportunity to be seen as “great politicians” worthy of literary examination.

Yet, as political biographies define which personal and political qualities suggest “greatness”, it could also be argued we tend to associate these qualities with men and masculinity. Male leaders’ gender is never discussed or explored in their political biographies. Masculinity is portrayed as the unseen norm while gender is an attribute only ever identified with women.

This argument gains further support from the fact there are more women in Australian politics than ever before, yet there remains a notable lack of political biographies covering their lives and stories. In my study, I examined Australian political biographies published in the past decade. Only four out of 31 were on women politicians.

This small minority includes Margaret Simons’ Penny Wong in 2019 and Anna Broinowski’s 2017 biography of Pauline Hanson, Please Explain.

There are three key factors that can explain the lack of biographies written on Australian women politicians.

First, as previously noted, there is the lack of gender parity in Australian politics. The 1990s saw a surge of women enter politics, partly due to Labor’s gender quotas. Yet at the moment, only 31% of the House of Representatives are women and all major leadership positions are held by men.

Read more:

Why is it taking so long to achieve gender equality in parliament?

Second, Australian political biography itself has a role to play here — the Great Man narrative is an enduring problem. It leads to an overemphasis on so-called “foundational patriarchs” and overlooks the impact of political players who don’t conform to this stereotype.

In the past decade, two biographies each were written on former Labor prime ministers Paul Keating and Bob Hawke and former Liberal prime minister Robert Menzies. Another biography on former Labor prime minister Gough Whitlam added to the ever-growing stack of tomes dedicated to these leaders.

Third, women politicians might be more hesitant to expose their private lives to the same extent as their male counterparts. Women politicians frequently experience sexist media coverage that often scrutinises their personal choices as a reflection of their professional capabilities. It is hardly shocking that they might be hesitant to cede agency over their own story and endorse an official biography.

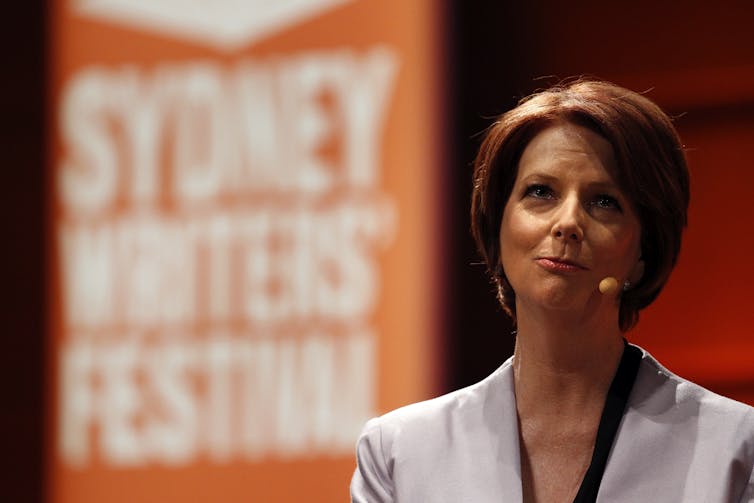

So, there are several glaring omissions in Australian political biography. Where is the biography of our first woman prime minister, Julia Gillard? Former deputy prime minister Julie Bishop is another that comes to mind.

There is also pioneering former Labor minister Susan Ryan, who was pivotal in the passing of the Sex Discrimination Act, the Equal Employment Opportunity Act and the Affirmative Action Act. And Natasha Stott Despoja, the youngest woman to sit in the Australian parliament and former leader of the Australian Democrats.

So where are all the great women political figures? Well, they’re in the memoir section.

Through my research, since 2010, I found 12 autobiographies and memoirs have been published by women premiers, party leaders, federal and state MPs and senators, lord mayors and, of course, our first and only woman prime minister (though I also counted over 30 written by male politicians).

Autobiographies can be a valuable way for women politicians to recover their voices, reassert their agency and reclaim their public identity by telling their own life story.

An ambition to take charge of their public image is a common thread running through these books, usually paired with a desire to expose sexism. Gillard’s autobiography My Story, published in 2014 (the year after she left politics), is a notable example of this, holding her opponents and the media to account for their frequently sexist behaviour.

Many women from across the political spectrum have now published comparable memoirs, including Labor MP Ann Aly, former Greens leader Christine Milne and former independent MP Cathy McGowan.

This year, former Labor cabinet minister Kate Ellis’ Sex, Lies and Question Time and former Liberal MP Julia Banks’ Power Play have provided two more examples of how women politicians — particularly those who’ve left politics — use the power of memoir to reclaim their stories and critique the sexist culture in parliament.

While it’s great women are using memoirs to voice their stories, we should not give up on conventional political biography.

As this genre continues to shape our understanding of political culture and history, it is more important now than ever that women are included to dispel once and for all the myth that their stories are not worth recording.

Rather than adding to the sexist speculation that women politicians experience, political biographers should offer their support for these stories to be told in a consensual and meaningful manner.![]()

Blair Williams, Research Fellow, Global Institute for Women’s Leadership (GIWL), Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article reporting on the winner of the 2021 Australian Literature Society (ALS) Gold Medal, Nardi Simpson, for ‘Song of the Crocodile.’

For more visit:

https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2021/07/21/190069/simpson-wins-2021-als-gold-medal-for-song-of-the-crocodile/

The link below is to an article reporting on the shortlist for the 2021 Furphy Literary Award shortlist.

For more visit:

https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2021/07/23/190315/furphy-literary-award-2021-shortlists-announced/

Joshua Black, Australian National University

Political memoirs in Australia often create splashy headlines and controversy. But we should not dismiss the publication of former Liberal MP Julia Banks’ book, Power Play, as just the latest in a genre full of scandals and secrets.

There is a long tradition of female parliamentarians using memoirs to reshape the culture around them. Banks — whose book includes claims of bullying, sexism and harassment — is the latest to push for equality and understanding of what life is like for women in Canberra.

There are many ways to tell your story — from social media posts to podcasts and speeches to parliament.

But there is something enduring about memoir. Sales figures aside, the political memoir can be a significant event. The inevitable round of media interviews, book tours and literary festivals can allow an author to stamp their broader ideas onto the public debate and shed light on the culture of our institutions.

Read more:

The ‘madness’ of Julia Banks — why narratives about ‘hysterical’ women are so toxic

They also have the advantage of usually being written when women have left parliament, and no longer need to place their party’s interests ahead of all others. Indeed, Banks tells us that her story is that of “an insider who’s now out”.

In 1972, Dame Enid Lyons (the first woman elected to the House of Representatives and wife of former prime minister Joe Lyons) published Among the Carrion Crows.

In her memoir, she offered a compelling insight into how she dealt with the male-dominated environment of parliament house. She recalled feeling like a “risky political experiment”, as if the very “value of women in politics would be judged” by the virtue of her conduct. She joyfully described how her maiden speech had moved men to tears.

In that place of endless speaking … no one ever made men weep. Apparently I had done so.

She also recorded key moments when she had vigorously presented her views in the party room and the parliament. She asserted the right of women to stand — and more importantly, to be heard — in parliament.

Since Lyons, women have continued to use autobiographies to promote women’s participation in politics and challenge the masculine histories of political parties.

When the ALP celebrated its centenary in 1991, it was the male history that was celebrated. Senator Margaret Reynolds (Queensland’s first female senator) “decided that the record had to be corrected”.

Reynolds’ writings on Labor women occurred alongside the ALP’s moves toward affirmative action quotas in the early 1990s. As well as a memoir, she wrote a series of newsletters called Some of Them Sheilas, and a book about Labor’s women called The Last Bastion. In it, she recorded the experiences and achievements of ALP women over the past 100 years.

In her 1999 book, Catching the Waves, Labor’s first female cabinet minister Susan Ryan acknowledged there was “a lot of bad male behaviour in parliament”. But she argued this should not “dissuade women from seeking parliamentary careers”. Importantly, Ryan saw her autobiography as a collective story about the women’s movement and its “breakthrough into parliamentary politics” in the 1970s and 1980s.

Read more:

Why is it taking so long to achieve gender equality in parliament?

While Labor women like Reynolds, Ryan and Cheryl Kernot were publishing their memoirs, few Liberal women put their stories on the public record. Former NSW Liberal leader Kerry Chikarovski’s 2004 memoir, Chika, was billed as the story of a woman who

learnt to cope with some of the toughest and nastiest politics any female has ever encountered in Australia’s political history.

In 2007 Pauline Hanson published an autobiography called Untamed and Unashamed, telling journalists, “I wanted to set the record straight”. But these were exceptions to the rule.

Following the sexism and misogyny that disfigured her prime ministership, Julia Gillard’s 2014 memoir My Story helped revitalise the national conversation about women and power. Hoping to help Australia “work patiently and carefully through” the question of gender and politics, Gillard promised to “describe how I lived it and felt it” as prime minister.

Importantly, she held not only her opponents but also the media to account for their gender bias. Critics like journalist Paul Kelly derided Gillard’s version of history as “nonsense”, but the success of her account suggests otherwise. My Story sold 72,000 copies in just three years.

In her 2020 book, Women and Leadership co-authored with former Nigerian finance minister, Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, Gillard interviewed eight women leaders from around the world, further showing how gender continues to shape political lives.

A political memoir can be fraught, however. After a decade in parliament, Democract-turned-Labor MP Cheryl Kernot published her memoir Speaking for Myself Again in 2002.

She had hoped it would argue the case for Australian women “participating fully” in politics to promote “their own values and interests and shift the underlying male agenda”.

But the release was quickly overshadowed by revelations of an extra-marital affair with Labor’s Gareth Evans (which were not in the book). Her book tour was halted amid the fallout. Kernot later despaired journalist Laurie Oakes — who broke the story — had managed to “sabotage people’s interest in the book”.

Others, such as Labor’s Ros Kelly, have told their stories in private or semi-private ways. Kelly’s autobiography was privately published as a gift to her granddaughter, but she also gives copies to women in politics, many of whom “have read it, and sent me really nice notes”.

In the past five years, several women from across the political spectrum have published life stories.

In her memoir, An Activist Life, former Greens leader Christine Milne argued that women should perform feminist leadership rather than being “co-opted into being one of the boys”. In Finding My Place, Labor MP Anne Aly, showed women of non-Anglo, non-Christian backgrounds belong in parliament too. Independents Jacqui Lambie and Cathy McGowan used their memoirs to show female MPs can thrive without the backing of the major parties.

Read more:

Politics with Michelle Grattan: Former MP Kate Ellis on the culture in parliament house

Most recently, former Labor MP Kate Ellis published Sex, Lies and Question Time, which includes reflections on the experiences of nearly a dozen other women in parliament.

For fifty years, Australia’s female politicians have used their memoirs to assert the equal rights of women in parliament, party rooms, and the media. Drawing on that lineage, Banks is the latest to help reveal and disrupt the sexism and misogyny in political life.![]()

Joshua Black, PhD Candidate, School of History, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The links below are to reports concerning the launch of Scribd in Australia.

For more visit:- https://publishingperspectives.com/2021/03/scribd-opens-a-digital-subscription-service-in-australia-covid19/

– https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2021/03/17/181240/scribd-launches-in-australia/

– https://goodereader.com/blog/e-book-news/scribd-launches-in-australia

Anna Johnston, The University of Queensland

In this series, we look at under-acknowledged women through the ages.

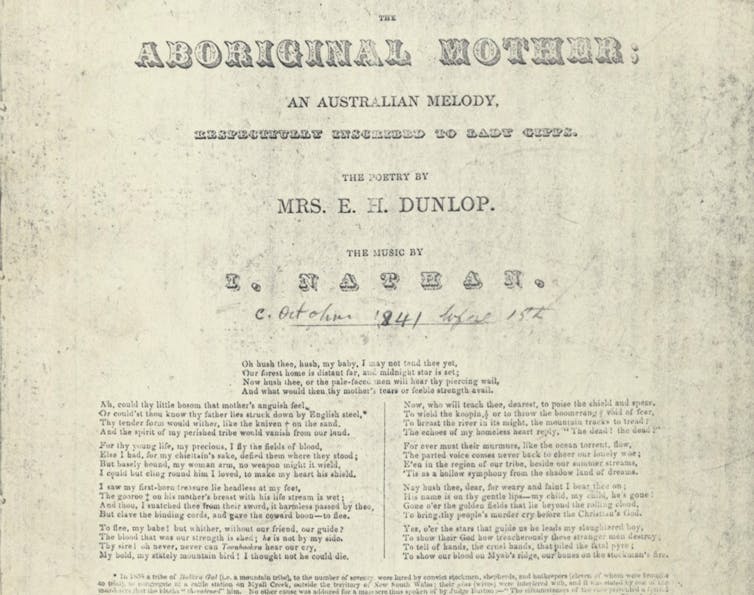

Eliza Hamilton Dunlop’s poem The Aboriginal Mother was published in The Australian on December 13, 1838, five days before seven men were hanged for their part in the Myall Creek massacre.

About 28 Wirrayaraay people died in the massacre near Inverell in northern New South Wales. Dunlop had arrived in Sydney in February, and the Irish writer was horrified by the violence she read about in the newspapers.

Read more:

How can we achieve reconciliation? Myall Creek offers valuable answers

Moved by evidence in court about an Indigenous woman and baby who survived the massacre, Dunlop crafted a poem condemning settlers who professed Christianity but murdered and conspired to cover up their crime. It read, in part:

Now, hush thee—or the pale-faced men

Will hear thy piercing wail,

And what would then thy mother’s tears

Or feeble strength avail!Oh, could’st thy little bosom

That mother’s torture feel,

Or could’st thou know thy father lies

Struck down by English steel

The poem closed evoking the body of “my slaughter’d boy … To tell—to tell of the gloomy ridge; and the stockmen’s human fire”.

The graphic content depicting settler violence and First Nations’ suffering made Dunlop’s poem locally notorious. She didn’t shrink from the criticism she received in Australia’s colonial press, declaring she hoped the poem would awake the sympathies of the English nation for a people who were “rendered desperate and revengeful by continued acts of outrage”.

Dunlop, the youngest of three children, was born Eliza Matilda Hamilton in 1796. Her father, Solomon Hamilton, was an attorney practising in Ireland, England and India. Her mother died soon after Dunlop’s birth, and she was brought up by her paternal grandmother.

Part of a privileged Protestant family with an excellent library, Dunlop grew up reading writers from the French Revolution and social reformers such as Mary Wollstonecraft.

In her teens, Dunlop published poems in local magazines. An unpublished volume of her original poetry, translations and illustrations written between 1808 and 1813 reveals her fascination with Irish mythology and European literature. She was deeply interested in the Irish language and in political campaigns to extend suffrage and education to Catholics.

In 1820, she travelled to India to visit her father and two brothers. The journey inspired poems about colonial locations — from the Cape Colony (now South Africa) to the Ganges River — that explored the reach and impact of the British Empire.

In Scotland in 1823, she married book binder and seller David Dunlop. David’s family history inspired poems such as her dual eulogy, The Two Graves (1865), about the bloody suppression of Protestant radicals in the 1798 Rebellion, during which David’s father Captain William Dunlop had been hanged.

The Dunlops had five children in Coleraine, Northern Ireland, where they were engaged in political activity seeking to unseat absentee English landlords, before leaving Ireland in 1837.

When The Aboriginal Mother was published as sheet music in 1842, set to music by the composer Isaac Nathan, he declared “it ought to be on the pianoforte of every lady in the colony”.

Dunlop often wrote about the Irish diaspora in poems which were alternatively nostalgic and political. But she also brought her knowledge of the violence and divisiveness of colonisation, religion and ethnicity to her writing on Australia.

Her optimistic vision for Australian poetry encouraged colonial readers to be attentive to their environment and to recognise Indigenous culture. This reputation for sympathising with Indigenous people — and her husband’s arguments with settlers in Penrith about the treatment of Catholic convicts — were widely criticised in the press.

This affected David’s career as police magistrate and Aboriginal Protector: he was soon moved to a remote location. There, too, local landholders campaigned against his appointment and undermined his authority.

When David was posted to Wollombi in the Upper Hunter Valley, Dunlop sought to expand her knowledge of Indigenous culture, engaging with Darkinyung, Awabakal and Wonnarua people who lived in the area.

She attempted to learn various languages of the region, transcribing word lists, songs and poems, and acknowledging the Indigenous people who shared their knowledge with her.

She wrote a suite of Indigenous-themed poems in the 1840s, publishing poems in newspapers such as The Eagle Chief (1843) or Native Poetry/Nung-ngnun (1848). These poems were criticised by anonymous letter writers, questioning her poetic ability, her knowledge and her choice of subject.

Some critics were frankly racist, refusing to accept the human emotions expressed by Dunlop’s Indigenous narrators.

The Sydney Herald had railed against the death sentences of the men responsible for the Myall Creek massacre, and Dunlop condemned the attitude of the paper and its correspondents. She hoped “the time was past, when the public press would lend its countenance to debase the native character, or support an attempt to shade with ridicule”.

Dunlop would publish with one outlet before shifting to another, finding different editors in the volatile colonial press who would support her.

Dunlop wrote in a sentimental form of poetry popular at the time, addressing exile, history and memory. She published around 60 poems in Australian newspapers and magazines between 1838 and 1873, but appears to have written nothing more on Indigenous themes after 1850. This popular writing also contributed to poetry of political protest, galvanising readers around causes such as transatlantic anti-slavery.

Read more:

Five protest poets all demonstrators should read

The plight of Indigenous people under British colonialism inspired many writers, including “crying mother” poems that harnessed the universal appeal of motherhood.

Dunlop’s poems The Aboriginal Mother and The Irish Mother are linked to this literary trend, but her experience of colonialism lent her poetry more authority than writers who sourced information about “exotic” cultures from imperial travel writing and voyage accounts.

In the early 1870s, Dunlop collated a selection of poetry, The Vase, but she was never able to publish. Family demands and financial constraints precluded it.

Dunlop died in 1880. Like many women of the time, her writing was neglected and forgotten, until it was rediscovered by the literary critic and editor Elizabeth Webby in the 1960s.

Webby identified Dunlop as the first Australian poet to transcribe and translate Indigenous songs, and as among the earliest to try to increase white readers’ awareness of Indigenous culture. Webby published the first collection of Dunlop’s poems in 1981.

Today, communities and linguists regularly use Dunlop’s transcripts for language reclamation projects in the Upper Hunter Valley.

Last year, 140 years after Dunlop’s death, Wanarruwa Beginner’s Guide — an introduction to one language of the Hunter River area — was published.

At the launch, language consultant Sharon Edgar-Jones (Wonnarua and Gringai) movingly recited one of the songs Dunlop transcribed: revitalising the words of the Indigenous women and men to whom Dunlop listened, when so few white Australians were listening at all.

Eliza Hamilton Dunlop Writing from the Colonial Frontier, edited by Anna Johnston and Elizabeth Webby, is out now through Sydney University Press.![]()

Anna Johnston, Associate Professor of English Literature, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

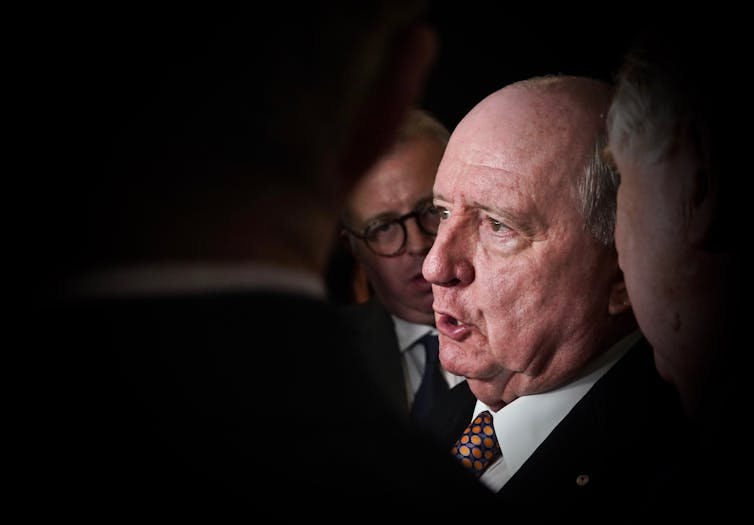

My heart sank last week to see conservative Australian commentator Alan Jones championing a contentious book about climate science which has gained traction in the United States.

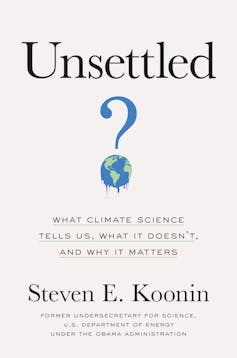

The book, titled Unsettled: What Climate Science Tells Us, What It Doesn’t, and Why It Matters, is authored by US theoretical physicist Steven Koonin. Notably, Koonin is not a climate scientist.

As the title suggests, the book’s bold central theme is that climate science is far from settled, and should not be relied on to make policy choices in areas such as energy, transport and economics.

Jones cited Koonin’s book in a Daily Telegraph column last week. He decried the “nonsense” of governments in Australia and abroad aiming for net-zero carbon emissions, saying it was as though Koonin’s book “didn’t exist”.

So does the book hold up? I have been researching and writing about climate change since the 1980s. I wanted to give the book a fair reading, so I put any preconceived thoughts aside and tried to fairly weigh up Koonin’s arguments. If true, they would be very important findings.

Koonin frames his book as a brave attempt to reveal how the climate science we’ve been relying on all these years is, in fact, uncertain. But the book’s major flaw is to imply these uncertainties are news to climate scientists.

This is patently untrue. Science is never settled. But there is enough confidence in the science to justify significant climate action.

Koonin opens the book by saying he accepts that Earth is warming, and humans are contributing to this. But he muddies the waters with passages such as the following:

Past variations of surface temperature and ocean heat content do not at all disprove that the (approximately 1℃) rise in the global average surface temperature anomaly since 1880 is due to humans, but they do show that there are powerful natural forces driving the climate as well.

In other words, Koonin says, the real question is “to what extent this warming is being caused by humans”.

No rational person could deny that natural forces drive the climate. The climate record shows significant climate changes long before humans existed; clearly we’re not responsible for the planet being much warmer many millions of years ago.

However the five assessment reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change have expressed steadily increasing confidence that humans are the dominant cause of global warming this century.

Koonin attacks former US secretary of state and now Biden climate envoy, John Kerry, who once said of climate change “the science is unequivocal”.

It is true to say climate science is somewhat uncertain. Science is always a work in progress. Scientific integrity demands a willingness to look carefully at new data and theories to see if they require us to revise what we thought we knew.

But Koonin is wrong to imply scientists are somehow unaware of, or deny, this uncertainty. To the contrary, I have heard decision-makers express exasperation when we scientists seek to qualify our advice on the basis that our knowledge is limited.

Every reputable climate scientist I know is always willing to look at new data. But policy-makers must make decisions based on the current scientific understanding.

Koonin states, accurately, that few in the general public receive scientific information directly from research papers. Most people receive climate change information after it’s been filtered by governments and the media – which, in Koonin’s mind, often overstate the seriousness of climate change.

However Koonin fails to note the opposite forces at play – governments and media organisations, such as the Murdoch press in Australia and Fox News in the US, which systematically misreport climate science and underestimate the climate threat.

Read more:

Climate explained: why is the Arctic warming faster than other parts of the world?

Koonin concludes by questioning the wisdom of reaching net-zero emissions in the second half of this century – a central goal of the Paris Agreement. He argues that when one balances the cost and efficacy of slashing emissions “against the certainties and uncertainties in climate science”, the net-zero goal looks implausible and unfeasible.

This is effectively an assertion that ignorance is bliss: because we don’t have perfect understanding that allows us to make exact projections about the future climate, we should not take serious action to reduce emissions.

Koonin proposes a different response: for society to adapt to a changing climate, and embrace “geoengineering” technology to artificially control Earth’s climate.

Both adaptation and geoengineering have their place in the climate response. But neither are sufficient substitutes for dramatically cutting carbon emissions.

Read more:

Solar geoengineering is worth studying but not a substitute for cutting emissions, study finds

Under the Hawke government, science minister Barry Jones was one of the first public figures in Australia to sound warnings about climate change.

Jones and I both appeared on a panel at a landmark climate conference in 1987. I recall Jones, when asked how decision-makers should respond, said we should consider the consequences of both acting and not acting.

If policymakers acted on inaccurate climate science, Jones argued, the worst that would happen is our energy would be cleaner – albeit, at that time, more expensive. But if the science was right and we ignored it, the consequences could be catastrophic.

Jones was essentially describing the precautionary principle, which is contained in a number of international treaties including the UN’s Rio Declaration, which states:

Where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation.

The principle demands we act to avoid disastrous outcomes, even if the science is uncertain. Because the uncertainty works both ways: things might get worse than we expect, rather than better.

The fundamental point of Koonin’s book is true, but irrelevant. The science is not settled – but we know enough to act decisively.

Ian Lowe, Emeritus Professor, School of Science, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article reporting on the shortlists for the 2021 West Australian Young Readers’ Book Awards (WAYRBA).

For more visit:

https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2021/02/18/162734/wayrba-2021-shortlists-announced/

You must be logged in to post a comment.