The link below is to an article that takes a look at Internet novels.

For more visit:

https://blgtylr.substack.com/p/i-read-your-little-internet-novels

The link below is to an article that takes a look at Internet novels.

For more visit:

https://blgtylr.substack.com/p/i-read-your-little-internet-novels

The link below is to an article that looks at climate change and Cli-Fi.

For more visit:

https://lithub.com/how-contemporary-novelists-are-confronting-climate-collapse-in-fiction/

The link below is to an article that looks at how to delete documents and ebooks from your Kindle library.

For more visit:

https://www.howtogeek.com/715730/how-to-delete-books-and-documents-from-your-kindle-library/

The link below is to an article that lists 15 ebook reader apps that the writer considers the best. As always, check out the comments section below the article for ‘alternative’ views as to what is the best ebook reader (oftentimes not listed in the article), especially if what you are after is not in the provided list. However, you should be able to find what you need in the list provided.

I, of course, use the Kindle ebook app whenever I need to use an app, though generally I use my Paperwhite. I do find the Moon Reader + app to be a very good ebook reader app also.

For more visit:

https://www.androidauthority.com/best-ebook-ereader-apps-for-android-170696/

Marlene Daut, University of Virginia

Following the July 7, 2021 assassination of Haiti’s President Jovenel Moïse and after one Haitian official requested that the U.N. and U.S. send troops to help stabilize the nation, many Haitian activists and artists recoiled at the prospect of yet another outside intervention.

The Haitian-American novelist Edwidge Danticat is one artist who has repeatedly railed against past U.S. occupations of Haiti. In her foreword to Jan J. Dominique’s “Memoir of an Amnesiac,” she highlights a tension that exists in Haiti’s collective memory – pride over the revolution for freedom and independence from France in 1804, and frustration over continuous foreign meddling, brought to a new height with a 20-year occupation by the U.S. military starting in 1915.

“Never again will foreigners trample Haitian soil, the founders…declared in 1804,” Danticat writes. “Yet in 1915, the ‘boots’ invaded,” which meant that Haitians like the father of the narrator in Dominique’s tale would “never truly know a fully free and sovereign life, having had not just his country but his imagination invaded and occupied by the Americans.”

A specialist in Haitian literary and historical studies from the University of Virginia, Marlene L. Daut has selected four Haitian-authored novels that sit with this contradiction, along with many others.

By guiding readers through Haiti over the past century, she shows how these contemporary writers magnificently paint the entanglements of memory, history and imagination that make Haitian art, from all times, so enduring and brilliant.

In “Memory at Bay,” Trouillot explores the ruthless juxtaposition that exists between Haitian President-turned-dictator François “Papa Doc” Duvalier, called “the Deceased” in her novel, and Haiti’s subjugated position in the Western world.

Many years after the death of Duvalier and the fall of his successor and son, “Baby Doc,” the Deceased’s bedridden wife tries to cast her husband as both a protector of the Haitian people and a target of the West’s quest for revenge.

“After all, how could the Western countries ever forgive or forget Napoleon’s debacle, the sorry defeat of the French army … and the rout of the French colonizers at the hands of an army of former slaves?” the Deceased’s wife thinks. The widow attempts to paint her husband as having been the only one to stand up to the “former colonialists, the one-time occupying power, and all those who wanted to use the country as a springboard for their ambitions.”

The attendant caring for her in a nursing home in France has a different memory of the Deceased and his legacy. Coming from a family devastated by the Tonton Makouts – Duvalier’s murderous henchmen responsible for the deaths of tens of thousands of Haitians – the nurse finds herself disgusted at having to care for an integral culprit in her country’s devastation.

“So many overlooked stories of men and women just guilty of having been alive at the wrong moment, in the wrong place,” she thinks, as she briefly contemplates whether to kill the widow. “My father, my uncle, the resister whose grandchildren will never know him, Madame So-and-So’s husband, the grocer’s cousin, his friend’s godfather, the mother of the little girl who will not be born, the boy who should have been born.”

Set in 1996, after the fall of the Duvalier regime and during the United Nations’ occupation of Haiti, this partly autobiographical tale tells the story of a never-named protagonist – a stand-in for Laferrière – who decides to come home to Haiti for the first time in 20 years.

Haiti has changed a lot during his exile in Montreal, where he was making his living as a writer. He no longer recognizes the capital, Port-au-Prince, which has seen massive migration from the countryside into the city. The result is overcrowding, famine and generalized misery.

In a chance encounter with a shoeshine man, the narrator is told that these changes mean “All the people you see in the street, walking and talking, most of them died a long time ago and they don’t even know it. This country has turned into the world’s largest cemetery.”

Such commentary encourages the narrator to write a book about “the other world.” He wonders “[i]s it here or elsewhere?” After unwittingly accepting from a powerful Vodou priest “the most terrifying offer anyone could make a writer: to take him to the kingdom of dead,” the narrator meets in succession the Vodou god Papa Legba, master of the crossroads, and Ogou Feraille, the god of war.

Ultimately, the narrator ends up as disappointed with the spirit world as he is with the mortal one. “This was hardly Dante’s inferno,” he remarks. “I’d been expecting…a universe so powerful and rich in symbols, so complex that it would have helped me… Instead, I ended up with a giggling adolescent goddess and the complaints of her father, the supposedly fearsome Ogou Feraille.”

All of this happens parallel to searing political commentary about the punitive and insulting measures forced upon Haiti by the world powers after the 1991 military coup that unseated President Jean-Bertrand Aristide. For example, along with U.N. “peacekeepers,” a comical cast of foreign investigators arrive to study why the people of the northwestern town of Bombardopolis do not need to eat for months at a time. The foreigners conclude that it is because they are all plants, and not human beings.

The irony of course is that foreign meddlers are the ones who have caused the starvation. “Hunger remains the most effective weapon,” one character wryly remarks.

Sometimes the sardonic humor stings a little too much: “When everyone starts joking in a country, you know that all hope is gone,” the narrator’s friend Manu complains. “Humor is the weapon of desperate people.”

In this work of historical fiction, Danticat transports readers to the Dominican Republic, to the border town of Alegría. There, Haitian workers are living “a cane life” – engaged in the brutal work of planting and cutting sugar cane, “travay tè pou zo, the farming of bones.”

Hewing closely to the historical record, Danticat captures the horrors of Dominican dictator General Rafael Trujillo’s massacre in 1937 of tens of thousands of Haitians living and working along the border. The more fictional sections follow the escape of Amabelle Désir, who had many years before witnessed the death by drowning of her parents, both migrant herbal healers, as they tried to cross the Dajabón River separating Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

Amabelle will eventually lose her lover, Sebastien Onius, to the troops of the “Generalissimo,” after Trujillo gives orders “to have all Haitians killed.”

As Haitian characters are tortured or executed because they cannot trill their Rs to pronounce “perejil,” the Spanish word for parsley, Haiti’s glorious revolutionary past seems to fade into the background of the torturous present.

“When Dessalines, Toussaint, Henry, when those men walked the earth, we were a strong nation,” one man who escaped the massacre states. “Those men would go to war to defend our blood. In all this, our so-called president says nothing…nothing at all to this affront to the children of Dessalines, the children of Toussaint, the children of Henry; he shouts nothing across this river of our blood.”

Near the end of “The Farming of Bones,” a guide taking visitors to King Henry’s famous Citadelle says, “Famous men never truly die…It is only those nameless and faceless who vanish like smoke into the early morning air.”

Beginning in 1938, just one year after Trujillo’s massacre, Depestre’s “Hadriana” trails the life, death and reemergence of a white French woman born in Haiti named Hadriana Siloé, who appears to mysteriously die while saying her wedding vows. She is then suspected of having been transformed into a zombie when her body goes missing from its grave.

During her funeral-turned-carnival, historical figures from different eras join the masked wake, as “historical memory” has gotten “mixed up to the point of ridiculousness.”

And so readers are treated to scenes of the Haitian emperor Jacques the First, who ruled Haiti from 1804 to 1806, playing table tennis with his partner, Joseph Stalin, while Venezuelan freedom fighter Simón Bolívar dances alongside King Henry Christophe, who became king of northern Haiti in 1811.

“This masked occasion had convoked three centuries of human history to [Hadriana’s] wake,” her childhood friend Patrick says. They “had come together to dance, sing, drink rum, and refuse death, kicking up the dust on my village square, which, in the midst of this general masquerade, took itself for the cosmic stage of the universe.”

In the end, it is not just history but all of life that appears to be one large carnival as the contours of death come alive on the streets of the living.

This tale has a happy ending, though. Decades later, Hadriana is revealed to be alive after all and describes how she miraculously escaped from the botched attempt to turn her into a zombie. She even gets married, not to her original fiancé but to Patrick, who has chronicled all that took place in her absence.

The true romance here may be that unlike so many of those who have disappeared in yesterday’s and today’s Haiti, Hadriana and Patrick live to tell their story.

[Over 109,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]![]()

Marlene Daut, Professor of African Diaspora Studies, University of Virginia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Margaret Kristin Merga, Edith Cowan University

Parents at a loss to find activities for their children during COVID lockdowns can encourage them to escape into a book. New research shows how reading books can help young people escape from their sources of stress, find role models in characters and develop empathy.

Recent media reports have highlighted a concerning rise in severe emotional distress in young people. Isolation and disruption of learning in lockdown have increased their anxiety. Given the recent surge in COVID-19 cases and lockdowns in Australia, parents and educators may look to connect young people with enjoyable activities that also support both their well-being and learning.

A lot has been written about the role of regular reading in building literacy skills. Now, my findings from a BUPA Foundation-funded research project on school libraries and well-being provide insight into how books and reading can help young people deal with the well-being challenges of the pandemic.

The findings suggest books can not only be a great escape during this challenging time, but also offer further well-being benefits.

We know that adults who are avid readers enjoy being able to escape into their books. Reading for pleasure can reduce psychological distress and has been related to mental well-being.

Reading-based interventions have been used successfully to support children who have experienced trauma. In a recent study, around 60% of young people agreed reading during lockdown helped them to feel better.

My research project confirms young people can use books and reading to escape the pressures of their lives. As one student said:

“If you don’t know what to do, or if you’re sad, or if you’re angry, or whatever the case is, you can just read, and it feels like you’re just escaping the world. And you’re going into the world of the book, and you’re just there.”

If you enjoy reading, there’s a good chance you have favourite characters who hold a place in your heart. The project found young people can find role models in books to look up to and emulate, which can help to build their resilience. A student described her experience reading the autobiography of young Pakistani activist and Nobel laureate Malala Yousafzai:

“I thought it was incredible how no matter what happened to her, even after her horrific injury, she just came back and kept fighting for what she believed in.”

Read more:

Nobel Peace Prize: extraordinary Malala a powerful role model

Other research has linked connecting with characters to mental health recovery, partly due to its power to instil hope in the reader. Building relationships with characters in books can also be used as “self-soothing” to decrease anxiety.

Young people also celebrate their affection for book characters in social networking spaces such as TikTok, where they share their enjoyment of the book journey with favourite characters.

Research supports the idea that reading books builds empathy. Reading fiction can improve social cognition, which helps us to connect with others across our lives. My previous work with adult readers found some people read for the pleasure they get from developing insight into other perspectives, to “see the world through other people’s eyes”.

In the project, a student described how reading books helped him to understand others’ perspectives. He explained:

“You get to see in their input, and then you go, ‘Well, actually, they’re not the bad guy. Really, the other guy is, it’s just their point of view makes it seem like the other guy’s the bad guy.’ ”

If parents are not sure what books will best suit their child’s often ever-changing interests and needs, they can get in touch with the teacher librarians at school. Even during lockdown they are usually only an email or a phone call away.

The library managers in the project played an important role in connecting students with books that could lead to enjoyable and positive reading experiences.

For example, a library manager explained that she specifically built her collection to make sure the books provided role model characters for her students. She based her recommendations to students on their interests as well as their needs. To support a student who had a challenging home life, she said,

“I recommend quite a number of books where we’ve got a very strong female character […] in a number of adverse situations and where she navigates her way through those.”

Fostering reading for pleasure is a key part of the role of the teacher librarian. They create spaces and opportunities for students to read in peace. They also encourage them to share recommendations with their peers.

In challenging times, many parents are looking for an activity that supports their children’s well-being. And as reading is also linked to strong literacy benefits, connecting them with books, with the support of their teacher librarian, is a smart way to go.![]()

Margaret Kristin Merga, Honorary Adjunct, University of Newcastle; Senior Lecturer in Education, Edith Cowan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Elizabeth Schafer, Royal Holloway University of London

I went to the theatre for the first time in 15 months to see the Theatre Royal Windsor’s new production of Hamlet. Starring Ian McKellen and directed by Sean Mathias, it really resonates in a time of ongoing pandemic. Mckellen’s very contemporary, teenage Hamlet slouches around in a hoodie and trackie bottoms, grieving, isolated and angry.

The setting, like the original, is the city of Elsinore, Denmark. In this version, COVID funerals are disrupted and truncated. Hamlet, a latterday prince, is a bisexual university student stuck at home with mum and step-dad when he wants to be back at uni in Wittenberg, hanging out with his friends and lovers.

Mental health issues afflict those in mourning, especially royalty. Hamlet muses “to be or not to be” as his lover, Horatio, gives the prince that most precious of things in lockdown, a haircut. Characters are overwhelmed by feelings of loss. Suicidal thoughts lurk. Denmark feels, and looks, like a prison. The government is morally corrupt.

Much of the play, this modern interpretation and Shakespeare’s original, speak to the circumstances and current climate in which we live. There is much in it to relate to and also learn from as our world widens and we learn to “live with the virus”.

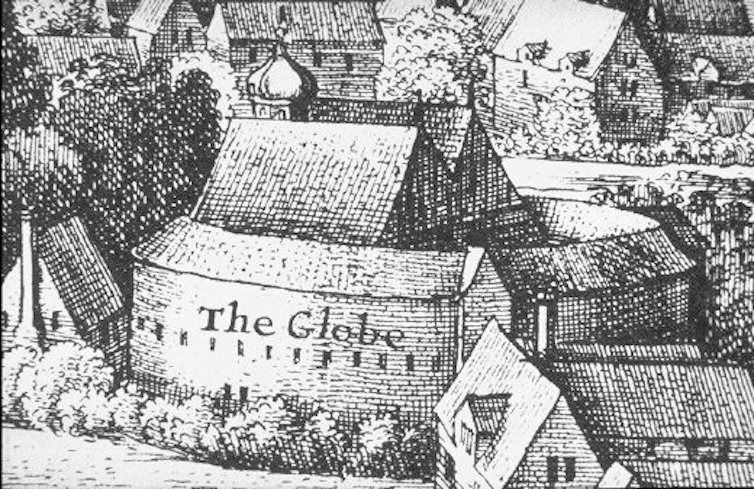

The spectre of plague and pandemic hung over much of Shakespeare’s life. He was born in April 1564, a few months before an outbreak of bubonic plague killed a quarter of the people in his hometown, Stratford-upon-Avon. Such pandemics would recur during his time in London in 1592, 1603, 1606 and then 1609.

When Shakespeare wrote Hamlet, usually dated around 1599-1601, feelings of grief, mourning and bereavement were probably at the forefront of his mind. His parents were very elderly by contemporary standards. Shakespeare’s father, John, died in September 1601 around 70 years of age. Five years earlier, in August 1596, Shakespeare’s son, Hamnet, had died aged 11, possibly of plague.

It is an uncanny coincidence that the name Hamlet is so close in sound to the name of Shakespeare’s son. The play is obsessed with fathers and sons, and how to navigate mourning a father’s death. It is full of speeches about grief and attempts to move on after bereavement. Hamlet is not alone in this as Ophelia and Laertes also suffer from unresolved grief in the play.

What galvanises Hamlet out of his emotional lockdown is theatre. When he hears travelling players are in town he leaps into action. Like so many in the audience he has really missed the theatre.

Despite the modern dress, Sean Mathias’ production eclectically evokes the theatre practices of the troupe in Hamlet. Most obviously, casting ignores age, ethnicity and gender, something which evokes the fact that Shakespeare’s stage had young men playing women. So while Jonathan Hyde is realistically cast as a plausible, efficient Claudius, the teenage Hamlet is played by an 82-year-old, while Francesca Annis who plays his elderly ghost.

Lee Newby’s set design also encourages audiences to think of early modern playing conditions, transforming the Theatre Royal stage into a black metal, faux Globe theatre with two banks of seats on either side of the stage and a gallery at the back.

As a result, the onstage audience are clearly on display, sharing light with the performers. The mandatory face masks offer a constant reminder of COVID, while blanking out the audience’s reactions, but they also offer a reminder that Shakespeare’s playhouse had to navigate its own pandemic and often had to negotiate sudden lockdowns.

When the weekly plague death count reached 30 in Shakespeare’s time, the playhouses closed. Plague transmission was not properly understood, but it was clear that people congregating created a super-spreader event of sorts.

Shakespeare, a player, playwright and, most importantly of all, a shareholder in the Globe, seems to have seized the moment and written prolifically during plague lockdowns. In 1592 he was writing narrative poetry – Venus and Adonis, The Rape of Lucrece – as plague raged.

The years 1603 to 1604, 1606, and 1608 to 1609 were also bad for plague, and seem to have given Shakespeare space to write. For example King Lear was performed at Whitehall Palace on Boxing Day 1606 at the end of a year of plague. From 1597 on, Shakespeare could also escape to his sprawling Warwickshire country mansion, New Place, one of the largest houses for miles, with at least 20 rooms.

By contrast, many players were desperate for any income and facing destitution. So, sometimes playhouses would reopen before the mortality rate fell to the level considered “safe”. The thought of what a “freedom day” was like in the early modern playhouse, with those standing (known as groundlings) pressed closely together in the yard, is perhaps even more daunting than watching people flood back now restrictions are lifted.

Now that so many restrictions have been lifted now in the UK since July 19, I am feeling very ambivalent about the shared experience of live theatre. The Theatre Royal created what feels like a very safe space and, personally, I could get used to having such a generous amount of leg room in front of me. In a COVID-secure theatre, there’s no need to get intimate with complete strangers while trying to squeeze through to your seat.

But after “Freedom Day”, the theatre is only insisting that masks remain mandatory for the audience onstage who are in such close proximity to the actors. The theatre will only “strongly encourage” the rest of the audience to mask up.

During the first decade of the 1600s, pandemic ravaged the country’s population and theatres were closed as often as they were open. This might be the case now too. Already productions have had to close to isolate, including London’s Shakespeare’s Globe, after positive cases among cast and crew. Maybe restrictions indoors could stave off more productions having to close. It took 30 deaths to close the playhouses in the 1600s, but now all it takes to close a theatre is one case of COVID.![]()

Elizabeth Schafer, Professor of Drama and Theatre Studies, Royal Holloway University of London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Daniel Chukwuemeka, University of Bristol

Hustler narratives have emerged as a genre in world literature since the mid 1960s. It is an expansive genre, but deals broadly with the shortcomings of any given political economy as seen from the perspective of characters who position themselves as both victims and villains.

There have been groundbreaking hustler narratives from the US – like The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965) written by Malcolm X and Alex Haley, and Donald Goines’s Dopefiend (1971). In recent times, critics have described the work of African American writers in this field as a type of crime fiction. They carry the expressions of people’s response to inner city problems such as de-industrialisation and police repression. The books represent individuals who operate outside the bounds of what American society might consider acceptable, just to survive.

Nigeria has made its own contribution to this field with its stories of political and religious hustle, sex worker narratives and many others about roadside hawkers, destitution, petty theft, and internet fraud. Notable examples include Akachi Adimora-Ezeigbo’s Trafficked (2008) and Igoni Barrett’s Blackass (2016). Other African entries include South African novelist Niq Mhlongo’s Dog Eat Dog (2004) and Congolese author Alain Mabanckou’s Black Moses (2017).

African hustler narratives represent the way people survive at the margins of postcolonial African economies. A distinct kind of African hustler narrative is the Nigerian e-fraud story, portraying characters who engage in cybercrime trying to make scam e-mail recipients part with their money – locally called “Yahoo Boys”. The narratives show how people attempt to overcome geographic and economic disadvantages by creating alternative networks.

In a recent paper, I analysed some of these e-fraud novels – and one in particular, I Do Not Come To You By Chance by Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani – to show that they fit the literary canon of hustler novels and to find out what they have to say as a critique of the Nigerian state and its economy.

In my study I looked at Nigerian hustler narratives in relation to another common trend in African literature today: Afropolitanism.

Afropolitanism describes the experience of African subjects who attain the status of global citizenship. They do this by connecting to other non-African expressions of identity, community and sense of belonging.

Both hustler and Afropolitan narratives highlight the possibility of migration as a way to move socially. But whereas the privileged Afropolitan has a real chance of migration, the African hustler can only access it through a backdoor channel.

For example, In Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah, Ifemelu’s migration to the US is through a legally documented process. In contrast, the female hustlers in Chika Unigwe’s On Black Sisters’ Street pay a pimp to smuggle them from Lagos to Antwerp.

However, instead of physical migration, the hustlers (e-scammers) in Nwaubani’s I Do Not Come to You by Chance resist poor economic conditions by creating an alternate digital universe. This they navigate by e-mail, for access to global locations of capital.

Nigerian hustler narratives establish e-fraud practice as an alternative economy and show how and why such economies emerge. They can also be a potent critique of young Nigerians’ exclusion from the postcolonial economy.

The protagonist of Nwaubani’s book, Kingsley, turns to e-fraud as a way out of poverty.

After independence in 1960, Nigeria continued to adopt the colonial model of an extractive economy, with its dependence on crude oil. Following the fall in global oil prices in the 1980s, Nigeria adopted a neoliberal economic policy called the Structural Adjustment Programme. But this failed to improve the lives of ordinary citizens and encouraged them to engage in capitalist pursuits.

Read more:

Meet the ‘Yahoo boys’ – Nigeria’s undergraduate conmen

Kingsley yearns to perform the traditional duties of a family’s opara (firstborn son), which include taking care of his siblings and widowed mother. He applies for work at Nigerian oil companies but none employs him. So he joins his uncle, Cash Daddy, in the informal economy of online fraud. He declares:

I was not a criminal. I had gone into [internet fraud] so that my mother could live in comfort and my siblings have a good education.

But in embracing e-fraud as an alternative to his economic exclusion, Kingsley recreates the same exploitative economic landscape that he seeks to avoid.

In one of his scam letters, he exploits the decadent image of Nigeria’s political economy and positions himself within it as a victim. He pretends to be the widow of former Nigerian head of state, General Sani Abacha, describing the persecution of the widow’s household following his death:

I have been thrown into a state of utter confusion, frustration and hopelessness by the current civilian administration. I have been subjected to physical and psychological torture by security agents in the country…

What Kingsley has done above is to weave his personal experience of economic deprivation into a scam e-mail. Terms like “hopelessness” and “psychological torture” serve to appeal to the scam target’s pity and earn their trust. But they simultaneously hold true about Nigeria’s economic uncertainties and Kingsley’s economic vulnerability. In this way, readers are introduced to the degenerate world of Nigeria’s postcolonial economy, one that emasculates the postcolonial subject.

In another scam e-mail he writes:

There is a lot of corruption in Nigeria and people get up to all sorts of devious things.

Kingsley’s class-climbing manoeuvres are therefore a by-product of a failing Nigerian economic system in which a parasitic state exploits the masses. It does so by privatising government assets and converting the common wealth to its advantage, excluding most citizens.

Kingsley’s story forms a critique of the Nigerian economic culture in which he is allowed first to starve and then to prosper.![]()

Daniel Chukwuemeka, PhD Candidate in African Postcolonial Writing, University of Bristol

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article reporting on the winner of the 2021 Australian Literature Society (ALS) Gold Medal, Nardi Simpson, for ‘Song of the Crocodile.’

For more visit:

https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2021/07/21/190069/simpson-wins-2021-als-gold-medal-for-song-of-the-crocodile/

You must be logged in to post a comment.