Charles Leonard

Beth le Roux, University of Pretoria

Books in South Africa don’t often make headline news. But a controversial subject, protests and disruptions at a book launch, and threats of book burning are sufficient to get South Africans talking about the place of books in society once again.

This is exactly what has happened with investigative journalist Pieter-Louis Myburgh’s latest book “Gangster State”.

“Gangster State” is an exposé of current African National Congress (ANC) Secretary General Ace Magashule’s alleged murky dealings as premier of the Free State province, and his rise to one of the governing party’s most influential positions. The book has stirred up passionate reactions, both for and against its contents.

This last happened in late 2017 when another investigative reporter Jacques Pauw published a similar book, “The President’s Keepers”. That book dealt with South Africa’s previous head of state, Jacob Zuma, who’s been closely linked to massive corruption. Zuma denies the allegations.

Read more:

Two books that tell the unsettling tale of South Africa’s descent

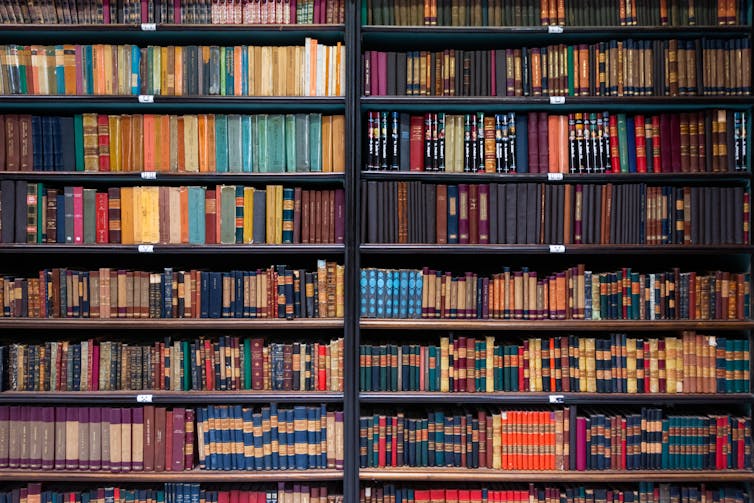

Clearly, this kind of book touches a certain chord in South African society. A quick glance through the top-selling books in the past few years shows that non-fiction, and particularly political non-fiction dealing with very topical events, is the most popular genre.

The trend can be traced back through a number of years, with nonfiction consistently dominating the Nielsen’s BookScan sales charts – the most comprehensive figures collected on book sales through commercial booksellers. This raises the question: why do political books do so well in South Africa?

Celebrities

This isn’t a uniquely South Africa phenomenon. Nonfiction is popular around the world. Celebrities’ memoirs or biographies, as well as history titles, are more likely to become bestsellers than any other kinds of nonfiction. Indeed, Michelle Obama’s memoir “Becoming” caused a paper shortage in the US towards the end of 2018, as it was reprinted in such large quantities and at short notice to keep up with audience demand. This title has now sold more than 10 million copies worldwide.

Where South Africa differs is in the balance of sales between nonfiction and fiction. In most of the largest publishing markets, fiction is bought at much higher rates than nonfiction. In the US, for instance, average sales for fiction titles are between 4 000 and 8 000 copies, while the nonfiction average is lower, at 2 000 to 6 000 copies.

In South Africa, it’s the reverse. Nonfiction outsells fiction. This is not a new trend, either: political books found a ready audience throughout the apartheid period.

There are a few categories of nonfiction that do particularly well: political nonfiction, South African history (especially political history), religious books – and the ubiquitous cookbooks. The authors that have the edge tend to be journalists rather than academics, probably because their writing is so much more accessible.

Statistically, too, men write more nonfiction than women in South Africa, and so are more likely to produce top-selling titles, as was found by one of my post-graduate students, Kelly Ansara, in her Master’s study of the gender balance in SA publishing.

South African trends

In analysing the publishing lists and sales figures of the local nonfiction publishers – Pan Macmillan, Jonathan Ball, Penguin SA, Tafelberg and Jacana, on the whole – another difference becomes apparent. Books by and about celebrities are not as popular in South Africa as in the US and UK. Their sales are thus less predictable.

For instance, while former Springbok rugby coach Jake White’s “In Black and White” sold more than 60 000 copies in a week in 2008, star rugby player Joost van der Westhuizen’s “Man in the Mirror” was less successful. Comedian Trevor Noah’s memoir, “Born a Crime”, has been extremely successful, but titles by local musicians and actors such as Bonang Matheba and Somizi Mhlongo have sold comparatively few copies.

The raft of competing titles that hit the shelves after the murder conviction of former Paralympian athlete Oscar Pistorius did not take off as well as expected. Excellent titles on topics as diverse as climate change and South African art sell a respectable number, but don’t make the bestseller list.

Many of the country’s nonfiction titles sell several thousand copies very quickly, but few of them have staying power. Current interest is intense in topics like state capture and corruption scandals. But it fades quickly, leading to a short shelf-life for a number of political books. Only a few gain the perennial interest and staying power of a title like “I Write What I Like” by Steve Biko or Nelson Mandela’s “Long Walk to Freedom”.

Making sense

Many commentators suggest that the interest in political and current affairs titles reflects a nation trying to make sense of its tumultuous political environment. The huge political and social shifts of the past 20 to 30 years are still influencing South Africans’ daily lives. With one corruption scandal following another, trust in the authorities is low. But citizens still seek authoritative overviews and answers – in the nonfiction titles that line our shelves.

There is little reason to predict that the trend will change. However, if the threats mount, then we may see authors and publishers shifting to less controversial topics. For now, it’s great to see books in the news again.![]()

Beth le Roux, Associate Professor, Publishing, University of Pretoria

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.