The link below is to an article that looks at the best comic reading apps for Windows.

For more visit:

https://www.makeuseof.com/best-comic-book-reader-apps-for-windows/

The link below is to an article that looks at the best comic reading apps for Windows.

For more visit:

https://www.makeuseof.com/best-comic-book-reader-apps-for-windows/

The link below is to an article that considers how reading ebooks changes our perceptions.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/reading-ebooks/

Daniel Cook, University of Dundee

Wander through Edinburgh and you will find glimpses of Scotland’s most famous novelist, Walter Scott, everywhere: pubs named after characters or places in his books, his walking cane and slippers in The Writers’ Museum, and snippets of his work adorning the walkways of Waverley train station – named after his first and most famous novel. And just outside, towering over Princes Street Gardens, his statue stands beneath an elaborate monument affectionately dubbed the “Gothic Rocket”.

Built in 1840, eight years after his death at the age of 61, the Scott Monument captures the immense regard in which Scotland held this international bestselling writer and son of Edinburgh. Scott’s adventurous historical stories, set against a dramatic backdrop of brooding mountains, dark lochs and lush glens, brought a vision of Scotland to the world that captured the popular imagination. The gripping tale of the Scottish outlaw Rob Roy has never been out of print since it was published in 1817.

As his friendly rival Jane Austen once quipped, Scott had two careers in literature. He quickly became Europe’s most famous poet in 1805 with the immediate success of his first narrative poem, The Lay of the Last Minstrel, the tale of two lovers on opposite sides of a clad feud.

A 1810 book-length versification of King James V’s struggles with the powerful clan Douglas, The Lady of the Lake would have secured his legacy on its own. Selling 25,000 copies in eight months, it broke records for poetry sales and brought its setting, the picturesque Loch Katrine and the Trossachs, to the attention of a fledgling tourism industry.

Scott also wrote songs and collected ballads for posterity, but after the success of his poetry, he turned to novel writing in his 40s. For nearly 20 years he produced a series of fat novels, which spread his reputation around the globe further still. Although dabbling in the gothic and picaresque styles popular at the time, Scott favoured historical themes, not only set in Scotland but also England, France, Syria and elsewhere, as far back as the 11th century.

Nobody before Scott had devoted so much space to Scottish characters and interests, on such a massive scale – not even 18th-century novelist and poet Tobias Smollett. Scott traversed the Scotland of 14th-century Perthshire and the Highlands of 1745, and gave a voice to the lairds and rustics alike.

These days, Scott’s writing has fallen out of fashion thanks in part to the sheer length of the novels. Arguably his best, The Heart of Midlothian still packs an emotional punch: Jeanie Deans walks from Edinburgh to London to obtain a royal pardon for her sister awaiting execution for the alleged murder of her baby. But, in keeping with the drawn-out journey, the story does suffer from slow pacing.

Waverley, Scott’s exploration of the Jacobite uprising of 1745, lends itself to political as much as literary analysis. And while it delivers stunning set pieces, some of them featuring Bonnie Prince Charlie himself, its first few chapters drag a little. But Scott rewards loyal readers with rich historical detail and sublime settings.

Fortunately for the casual reader, Scott was more than a novelist. He was also a master of the short story, and wrote 17 or so shorter fictions, many of which have been all but ignored by scholars who prioritise the major novels. Five of his best short pieces can now be read for free online.

Scott contributed at least two stories to Blackwood’s Magazine, the leading literary periodical in Edinburgh: The Alarming Increase of Depravity Among Animals and Phantasmagoria. The first is a sort of true-crime animal fable in which animals are complicit in wrongdoing; the second, a bizarre Gothic pastiche in which the narrator (a sentient shadow) is far more interesting than the benign story it offers.

Another, Wandering Willie’s Tale, is delivered by a blind piper, revolving around the grisly death of a despotic laird and some missing money. A hellish underworld, a demonic monkey, a blatantly biased narrator: such things make the story wildly unpredictable – and far removed from the grand jousts and royal intrigues found in his historical novels.

The Tapestried Chamber is an ingenious ghost story in which the ghost barely features, but it still sends shivers down the spine, such is Scott’s gift for building atmosphere through dialogue. Where novels seek closure, typically with happy endings, short stories can leave plotlines unresolved. Novels comfort us, short stories can confront.

Although Scott is rarely thought of as a short story writer today, in 1827 he did produce a collection of short fiction, Chronicles of the Canongate, in which two standout pieces merit a wide audience: The Two Drovers and The Highland Widow. Here, Scott is perhaps at his most political, in the real sense: focused not on battles and courts but on everyday life.

The first follows a Highlander and a Yorkshireman on their journey south into an increasingly hostile environment. Initially their cultural differences are countered by a mutual love of music. But, tired of the casual xenophobia thrown at him, the Highlander kills his colleague. The suddenness of the act startles the reader, especially those used to the slower pacing of the novels.

The Highland Widow captures the conflicted mood of a young lad who, seeking better fortune, enlists in the Black Watch to the fury of his staunchly Gaelic mother. Drugging her son so he misses his appointment, she dooms him to military execution, and herself to a hermit-like existence. Although written in a sentimental style popular at the time, the story finds much to say about national tensions, military occupation, and cultural conflict in the lives of post-Union Scots.

For the modern reader Scott’s short stories are far bleaker than you might imagine, and they are all the more riveting for it. Gothic rocket indeed.![]()

Daniel Cook, Reader in Eighteenth-Century and Romantic Literature, University of Dundee

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Bryan Yazell, University of Southern Denmark

Typically set in the future, climate fiction (or “cli-fi”) showcases the disastrous consequences of climate change and anticipates the dramatic transformations to come. Among the various scenarios cli-fi considers is unprecedented population displacement due to droughts and disappearing coastlines. These stories echo assessments from the International Organization for Migration, which warned as early as 1990 that migration would perhaps be the “single greatest impact of climate change”.

The scale of climate change, which has unfolded over generations and across the planet, is notoriously difficult to represent in fiction. Indian novelist Amitav Ghosh elaborated on this problem in The Great Derangement. According to Ghosh, the political failure to combat climate change is a symptom of a deeper failure in the cultural imagination. Simply put, how can people be expected to care about something (or someone) they can’t adequately visualise?

When it comes to representing climate migration, prominent US cli-fi takes on this imaginative problem by returning to familiar templates. These ideas operate under assumptions about what drives migration and depends upon prejudices about who migrants are. For example, in some of these stories characters will be noticeably shaped by the stereotype of “illegal” immigrants from Latin America.

Employing such well-known ideas can help get points across about a potential future but there is a more compelling way to represent climate migration. Stories can be grounded in reality without entrenching harmful stereotypes or

disregarding the very real climate migrants who currently exist in the US today.

Paolo Bacigalupi’s novel, The Water Knife, is set around the US-Mexico border. Permanent drought in the Southwest has turned the region’s population into refugees who desperately seek passage into neighbouring states and — most optimistically — north into Canada.

The novel’s borderland setting is heavy with political subtext. The southern border looms large in anti-immigration campaigns, which perpetuate misleading claims that the region is under siege from migrant groups. However, the novel is less interested in dispelling these myths than in redirecting their emotional power.

Asking readers to imagine themselves in the shoes of Latin American migrants today is an effective tool in literature. For example, John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath famously asked readers to sympathise with Dust Bowl migrants at a time when so-called “Okies” were subject to disdain. But Steinbeck’s novel also helped readers imagine these migrants’ plight by stressing how thoroughly American (and white) they were.

However, The Water Knife tasks readers with imagining the whole of the US becoming a country like Mexico. Angel, a central character in the novel, remarks that the violence he sees in Arizona reminds him of “how it had been down in Mexico before the Cartel States took control completely.” The book suggests here that the problems that drive large scale migration are not unique to any single part of the world, which is good. But at the same time, it also imagines a scenario where the societal violence associated with Mexico moves into the US. The warning is “change your behaviour now, lest you make the US like Mexico”. This doesn’t serve to help readers understand Mexico or the plight of migrants but reinforces ideas that both are bad realities we would rather avoid – to become Mexico and a refugee is to fail but if you act now you can avoid becoming like them.

The Water Knife demonstrates how narratives that wish to raise awareness about the plight of climate migrants must tread carefully. Hoards of desperate migrants are a common motif in apocalyptic science fiction, but they are also familiar subjects in xenophobic political campaigns.

So long as people believe that climate migration will only become a problem for wealthy countries in the future, they might also believe that they can simply close their borders to the climate migrants when they come. In the meantime, dehumanising stereotypes about refugee armies obscure the very real harm facing migrants in the US today. So, while these stories want to encourage a more sympathetic view of migrants, they can have the opposite effect.

But climate migration isn’t just a problem for less affluent countries in the future. It is well underway in the US.

From catastrophic wildfires on the West Coast to mega-hurricanes along the Gulf, environmental disasters already afflict large segments of the population. The effects of forced migration due to Hurricane Katrina in 2005, for example, are apparent in the lower rate of return of New Orleans’s Black population.

To highlight cli-fi’s shortfalls is not to undermine its important contributions to environmental activism. These are stories that want to do more than raise the alarm. They want us to think more proactively about responding to disaster and caring for others now. This sense of urgency might explain why much of cli-fi depends upon pre-existing (and flawed) migrant stereotypes rather than ones more in step with climate migration today. Perhaps it’s quicker to push people to action by mobilising old ideas than constructing new ones.

However, these stories need not look to foreign cases or draw outdated parallels to make climate migration a compelling scenario. Rather, they can look inward to the ongoing climate crises afflicting Americans today. That these affected groups are disproportionately Indigenous and people of colour should remind us that the dystopian elements of many cli-fi stories (widespread corruption, targeted violence, and structural inequality) are facts of everyday life for many in this country. People should be shocked that these things are happening under their noses, enough to inspire action now rather than later for problems in the distant future.![]()

Bryan Yazell, Assistant Professor in the Department for the Study of Culture, University of Southern Denmark

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Elizabeth “Biz” Nijdam, University of British Columbia

Comics about refugee experiences are not new. After all, even the superhero created by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, Superman, is a refugee who landed on Earth after his flight from Krypton.

However, recently there has been renewed interest in comics representing migrant experience — namely, that of refugees and asylum-seekers. Since 2011, in particular, and the start of the civil war in Syria, comics and graphic novels have become an important forum for examining global forced migration.

These so-called “refugee comics” range from newspaper comic strips to webcomics and graphic novels that combine eyewitness reportage or journalistic collaboration with comic-book storytelling. These stories are written with the aim of incorporating the points of views of refugees, artists, volunteers or journalists working on-the-ground in displaced communities, war zones and along the migrant journey. They sometimes emerge in collaboration with human rights organizations.

In light of their subject matter, these comic artists contend with complex and distressing themes that are otherwise difficult to represent.

They draw on the traditional comics format, including the medium’s sequential nature, the use of panel walls and a combination of text and image to foster empathy and compassion for the migration journey. In so doing, they aim to give voice to asylum-seekers and refugees, part of 80 million individuals and families forcibly displaced worldwide, whose anonymous images often appear in western media.

These comics are typically drawn by western cartoonists, based on direct testimonies by migrants and refugees or those who have worked with them or encountered them. They are typically not by refugees but about refugees. Scholar Candida Rifkind, who studies alternative comics and graphic narratives, explores how comics about migrant experience often emerge when witnesses to migrant stories grapple with feelings of “shame, guilt and responsibility” to make western society at large more aware of and responsive to refugee realities.

These narratives prompt ethical questions about what it means to tell a story and who has the right or responsibility to do so. While questions about the power relations embedded in how these texts are produced remain, comics on global forced migration are still an important avenue for interrogating the representation of migrants and the socio-political circumstances surrounding their journeys.

These comics also challenge what may otherwise be relayed in mainstream media as the story of a global migrant crisis that has no human face, with perilous effects for migrants who face xenophobia and hate. In Rifkind’s words, they are a kind of intervention into “the photographic regime of the migrant as Other that has emerged as the dominant visual record” of contemporary globalization.

In comics about forced migrant experiences, people experiencing life as refugees become centred as the subjects of their own stories. But cartooning can allow storytellers to represent individuals anonymously, making it easier for people “to give testimony fully and candidly,” while affording them the specificity of their humanity.

There can be consequences for refugees who testify about their circumstances and the oppression and violence they encounter. Photographic evidence of unlawful or undocumented residence in migrant encampments or someone’s journey to seek asylum could in fact jeopardize a person’s safety and end goal.

Notably, comics on forced migration are also inventing new visual strategies to recount refugee experiences. Artists use panel borders to add a layer of storytelling that typically vacillates between the creators’ ability to represent a specific experience, emotion or event and the very inability to portray some forms of trauma and lived experience.

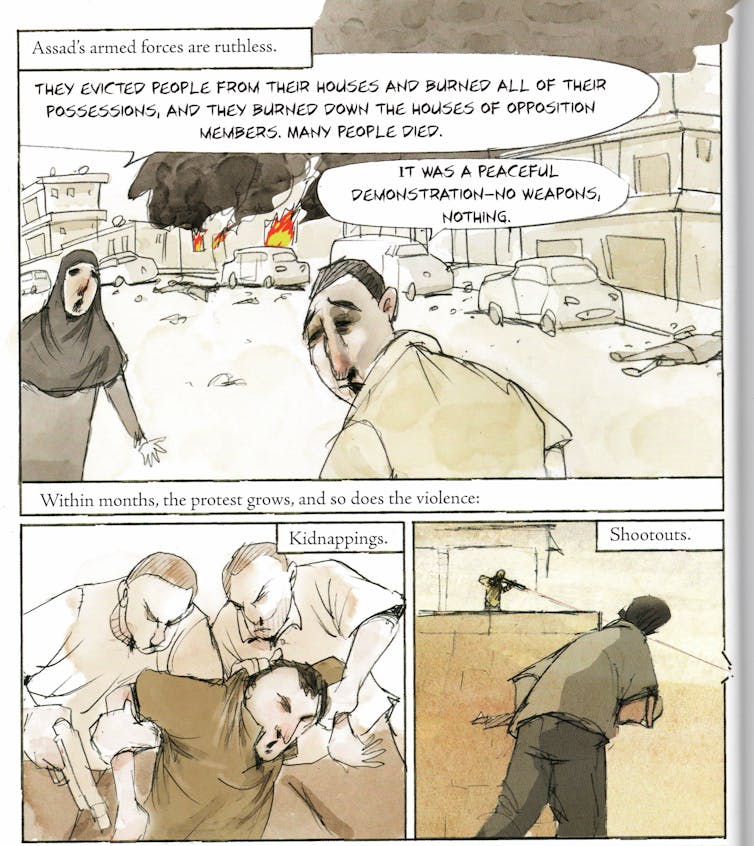

In The Unwanted: Stories of the Syrian Refugees (2018), American author and illustrator Don Brown depicts moments of hardships and hope in the lives of the refugees that Brown met in three Greek refugee camps in Ritsona, in Thessaloniki and on Leros.

The violence encountered by the refugees of Brown’s graphic novel is the only graphic element that breaks through panels. Bullets fracture the panel edges, bombs explode out of the picture planes and toxic smoke rises through the frames.

Brown draws on the convention of exceeding and playing with borders in comics to demonstrate a relationship between violence and transgressing borders. Not only did violence in Syria force many of its citizens to journey in search of safety and freedom; fleeing Syrians also also faced violence and hostility beyond the borders of their homeland on their journeys and where they landed.

The panel borders in Threads: From the Refugee Crisis (2016) by British cartoonist, non-fiction author and graphic novelist Kate Evans are comprised of clippings of delicate lace. Threads is a socio-political and cultural critique rooted in the author’s experience volunteering in the largest though unofficial refugee encampment in Calais, France, which operated from January 2015 to October 2016.

My research has examined how this lace integrated into the comic is more than simply an analogy for the intertwining factors and complex relationships that emerged in Calais. The lacework is a fundamental structuring principle in Evans’ text that engages with the region’s history of lacemaking, Calais’ most essential industry and refugee experience simultaneously.

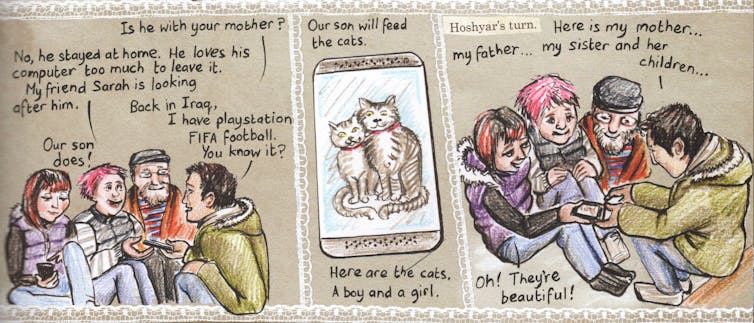

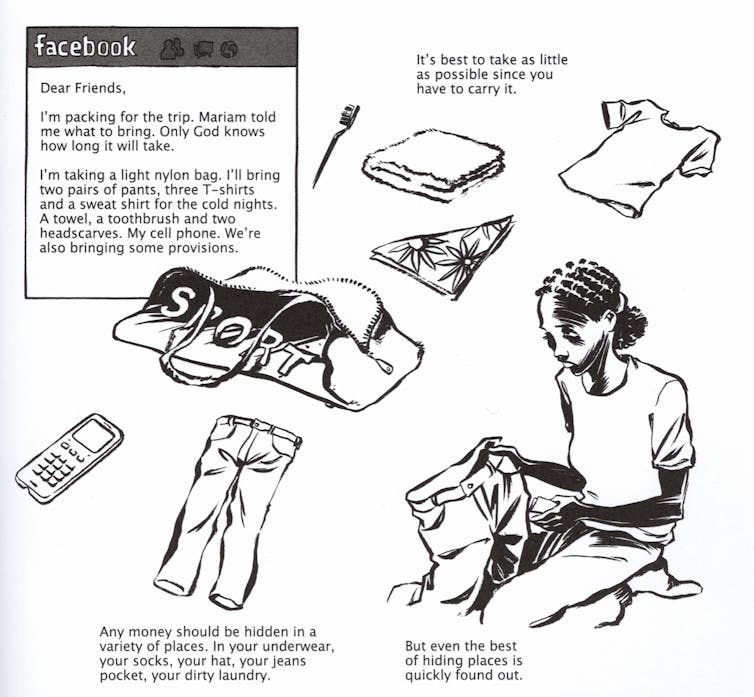

The aesthetics of the smartphone have also begun to play a role in the representation of refugee experiences in comics. Smartphone screens and social media platforms function as frames within some stories.

German graphic designer and cartoonist Reinhard Kleist embeds social media into the comics grid in An Olympic Dream: The Story of Samia Yusuf Omar (2016). The story recounts how Omar, the Somali Olympic runner, died by drowning en route to Italy in 2012.

Some of the story is narrated through Facebook posts based on interviews conducted on that platform with Omar’s sister and a journalist who had interviewed and known Omar.

Somalian athletes lifted up Omar’s story to draw attention to the Olympics as a venue to promote awareness about global conflict and peace. In Kleist’s introduction, he writes that too often, “abstract numbers represent human lives.”

This comic and others joins several examples of new media, such as viral videos, mobile games and documentary film that are highlighting the role mobile devices can play during the migration journey.

Through their personal stories, comics on forced migration humanize refugee experience. This category of graphic narrative also offers opportunities for articulating the complexity of refugee experience through the narrative techniques and visual strategies of comic art.![]()

Elizabeth “Biz” Nijdam, Assistant Professor (without review) of German, University of British Columbia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Elizaveta Poliakova, York University, Canada

A large publishing takeover has many in the book industry concerned about the potential lack of content diversity in the future. In the fall, Penguin Random House announced it would be taking over Simon & Schuster.

This has prompted an investigation by the United Kingdom’s Competition and Markets Authority into whether the deal would mean a “substantial lessening of competition within any market or markets in the United Kingdom for goods or services.” In Canada, independent publishers have called for a similar review.

Meanwhile, last winter, Coteau Books reported that it entered into bankruptcy protection and closed its operations.

As reported by Stephen Henighan in The Walrus, its closure, and the folding of a Montréal bookstore known for its support of cultural events are “signs that the infrastructure for publishing and distributing Canadian books may be crumbling.”

Even before the pandemic, changes were afoot in publishing. Some authors had criticized the fact that it was difficult for entry-level writers to publish and make a living because a small number of cult-status authors dominate the market. BIPOC and queer authors have also been under-represented in traditional publishing deals, as have books that push the boundaries of mainstream genres.

Read more:

Cultural appropriation and the whiteness of book publishing

The smash success of 50 Shades of Grey, first self-published as fan fiction and then picked up by a major publisher, was a game-changer for starting discussions about categories of literature traditionally assumed to not have the capacity to generate a large audience base. It also generated conversations about the future of independent publishing at large.

In the midst of a shifting publishing industry, some authors are driven to experiment with how they deliver their work to readers, which includes novel forms of book production independent from the traditional publishing gatekeepers.

During the pandemic, under pandemic control measures, some are spending more time reading. An online survey by BookNet Canada found that 58 per cent of Canadian readers said they were reading more in the pandemic based on 748 online responses.

But who benefits from the apparent increase in reading? Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos had his net worth double to over $200 billion during 2020. Meanwhile, Canada’s most well-known book retailer, Indigo, reported last June that it had to close 20 locations across the country.

In Canada, book sales were down by 20 to 40 per cent at the start of the pandemic. BookNet’s research team surveyed 51 domestic publishers who flagged that with the sudden closure of retail spaces, the industry experienced a decrease in sales of three million units in the first half of 2020 compared to the sales data from 2019.

This is troubling for local markets in particular because oftentimes big-box stores, online retailers and international conglomerates do not promote homegrown talent. Small publishers advance local writers or foster writing and reading communities, and without them, it is harder for authors to become noticed due to the abundance of international competition.

However, there is a glimmer of hope as some small local bookstores are seeing a consistent drive of shoppers who have been buying local. With pandemic closures or library restrictions, it seems some readers do seek out books from local book vendors. However, there is no way of knowing whether this boom in promoting local businesses will continue.

In contrast to the huge gap in sales that local presses experienced in the past year, Penguin Random House saw a drop in revenue by less than 10 per cent. The company is now in a position to acquire Simon & Schuster for over US$2 billion. In November, Vanity Fair reported that this merger would mean that one out of every three books would be produced by the publishing giant.

If the merger happens, there will only be four main global publishers: Penguin Random House (and Simon & Schuster), HarperCollins, Macmillan and Hachette Book Group. Domestic presses will be affected by this merger who are already struggling to compete in the damaged marketplace.

The Association of Canadian Publishers, which represents more than 100 Canadian owned and controlled book publishers, says the potential consequences of the merger can include effects on staffing, lack of media coverage for domestic businesses and even shelf space in book stores..

Similarly, The Writers’ Union of Canada, representing more than 2,000 Canadian authors, highlights that writers will also face challenges related to their earning potential if the merger goes through.

One drawback of self-publishing can be both stigma based on the possibility that one’s work has been rejected by a traditional publisher and potentially missing editing and quality control of traditional publishers. But some self-publishers now employ editors both on a paid and volunteer basis.

There is a drive to alleviate some of the stigma surrounding self-publishing, with some writers expressing that their career should not be dictated by traditional mainstream publishers. For all these reasons, self-publishing is becoming a more appealing option for many writers.

Self-publishing refers to authors taking on full financial responsibility of the production, distribution, and marketing stages of a project for which they can hire individuals on a freelance basis.

A number of self-publishing platforms like Lulu and Smashwords reported an increase in sales of self-published titles starting with March 2020 when COVID-19 lockdowns began. One reason for this rise is the production of ebooks. Electronic books are convenient to buy when a significant number of people spend a large portion of time online at home.

Amazon’s Kindle Direct Publishing boasts that in 2020, in India, “thousands of authors” published their work on the platform — reportedly double the number of authors from the year before.

Being a self-publisher means authors control when to publish books and make them available to the readers. For instance, summer releases were delayed by many small presses due to the pandemic. It may be that self-published authors gained audiences who were waiting for new releases during this standstill in the publishing sector.

In the past 10 years, self-publishing has kept growing as an industry potentially due to ebook adoption and online publishing companies. It is difficult to trace the actual number of self-published books since some platforms like Amazon assign their own product numbers, making that data private.

But Bowker, a company which provides bibliographical information (such as ISBN data) to those working in the publishing industry, reported an increase of self-published titles in the last decade. Bowker registered 148,424 print self-published books with an additional 87,201 ebooks in 2011.

Only six years later, in 2017, the number of self-published books was more than a million, according to the company’s records. The numbers kept rising the following year, with over 1.5 million self-published books registered in Bowker’s system.

These developments indicate that self-publishing certainly has the possibility to have a permanent place in the publishing ecosystem. These new publishing practices might become appealing to authors who could produce their work and make it available to the public without any gatekeepers.![]()

Elizaveta Poliakova, PhD Candidate, Communications and Culture, York University, Canada

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Tarminder Kaur, University of Johannesburg; Gerard A. Akindes, Northwestern University, and Todd Cleveland, University of Arkansas

The efforts of a range of academics across Africa have produced a new anthology of articles about sport on the continent. It’s an important book because it’s a subject that’s been largely neglected.

Sports in Africa, Past and Present engages with the core themes that have emerged from a series of conferences. Chapters provide an array of sporting windows through which to view and understand key developments in Africans’ experiences with leisure and professional sporting activities.

The history of African sports is also a history of Africans’ reception and appropriation of an assortment of “modern sports” that European colonisers introduced. If Europeans colonised Africa, as the maxim goes, with a gun in one hand and the Bible in the other, they were also equipped with soccer, rugby and cricket balls.

Notwithstanding the intentions of the colonial powers, historians of African sports have established that the indigenous practitioners were hardly passive consumers. They contested various aspects and fashioned new meanings of these sports.

Various chapters address the roles that sport played during and after decolonisation. It helped shape local and national identities in newly independent African states. They also look at the ways in which individuals, communities and governments have used sports in contemporary Africa for social and political ends.

One of the themes in the book is the impact of colonisation, and how African players responded to various restrictions on their participation.

Africans were typically banned from white settlers’ sports clubs and associations. They often responded by forming teams and leagues of their own. This helped foster the development of distinct identities. In certain cases, these autonomous efforts at sporting organisations even simulated institution building in an imagined post-colonial state.

Trishula Patel’s chapter on cricket in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), for example, examines how the game helped reinforce various identities of the resident Indian community. Members struggled to negotiate racial discrimination at the hands of the white settler regime. Mark Fredericks demonstrates how the end of apartheid in South Africa, and the attendant unification of rugby and other sports leagues, signalled the death knell for community sports. In practice this meant the end of mass-based sports in black communities.

David Drengk’s chapter on surfing along the then Transkei Wild Coast and Todd Leedy’s chapter on the history of bicycle racing complicate ideas of interracial interactions during the apartheid era. Meaningful interactions could and did occur between black and white South Africans, or at least basic tolerance and respect.

The Nigeria women’s national soccer team has faced gender discrimination in a deeply patriarchal society. Chuka Onwumechili and Jasmin M. Goodman set out how players have used a series of sports-related strategies to push back against a range of sexist structures and entities. These include the Nigerian Football Federation.

Solomon Waliaula’s chapter offers significant insight into the pay-to-watch football kiosks that are ubiquitous throughout the continent, though his focus is on Kenya. He refutes the notion that because participants pay to watch European soccer, western culture dictates the dynamics in these settings. Instead, he argues, these spaces function based on local realities, cultural norms and social relations.

Christian Ungruhe and Sine Agergaard consider the acute challenges that West African football migrants face in Europe when their playing careers end.

Going back in time, Francois Cleophas reconstructs the experiences of Milo Pillay, a South African-born ethnic Indian physical culturalist. His weightlifting story illustrates the racial challenges that athletes faced, and at times surmounted, during the apartheid era.

Michelle Sikes uses the example of elite sprinter Seraphino Antao to highlight the challenges and opportunities that sports generated in the final years of British colonial control in Kenya and early independence. In an attempt to cultivate a common identity and purpose, leaders opportunistically trumpeted Antao’s successes. Politicians throughout the continent similarly used sports to build national unity in the aftermath of imperial overrule.

Marizanne Grundlingh examines the museum associated with South Africa’s Comrades Marathon, the world’s oldest and largest ultramarathon. In particular, she considers the ways that the race is remembered through gift-giving. Former participants donate various items for display, adding to the emerging subfield of sports as heritage.

Research on sports in Africa has gained considerable traction. But, like books such as Sports in Africa, the introduction of this topic into the classroom has lagged behind.

Three chapters address course design, approaches and learning outcomes. They also consider how African sports content can hone students’ critical analysis capabilities, digital research methods and intercultural learning skills.

Todd Cleveland draws on his experiences teaching the history of sports in Africa to offer lessons and insights. Matt Carotenuto’s chapter brings the reader into the world of a liberal arts institution. He offers advice based on his experiences teaching courses in African athletes and global sport.

Peter Alegi’s chapter looks at his experiences teaching an undergraduate seminar that examines the intertwined relationships between sports, race and power in South Africa.

We hope that the book can help precipitate positive change in the classroom and on the continent. And that it can enable practitioners, supporters and observers to better understand the lifeworlds in which sports are played and take on meaning.

This article is the first in a series examining African sport. The articles are each based on a chapter in the new book Sports in Africa: Past and Present published by Ohio University Press.![]()

Tarminder Kaur, Postdoctoral Fellow, University of Johannesburg; Gerard A. Akindes, Adjunct associate, Northwestern University, and Todd Cleveland, Associate professor, University of Arkansas

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Isabel Hofmeyr, University of the Witwatersrand

Bhekizizwe Peterson was one of South Africa’s foremost humanities scholars. Internationally renowned as an award-winning film writer and producer, he was a leading practitioner of community theatre, a literary and cultural critic and a public intellectual. His work straddled the academy and the community, foregrounding the knowledge of ordinary people.

In a round table discussion on his award-winning and acclaimed film Zulu Love Letter, Peterson observed:

It was created as a love letter to those who passed on and those still tasked with creating a better future for all.

For him, black cultural production always stands athwart past and future. Its makers are located in the midst of things, thrust into violent and unequal plots not of their own making. He believed that the black humanities offered unique resources for negotiating these contradictions. Literature, performance, theatre, film, music and art could, as he said:

facilitate dialogic and critical deliberations on individual and collective experiences and dreams.

The astonishing corpus that he created across his career – comprising film, television and theatre-making, creative writings, scholarly and critical works – were guided by these lode stars. The range of genres and media that he mastered speak to an important point: for him, what one created was as important as how and where one worked. Theoretical reflection went hand-in-hand with practice; knowledge had to be made in and outside the academy. Means and ends were inseparable; means became ends through the ethical practice they enacted.

I first met him in 1985 when he signed up for an Honours degree at the University of the Witwatersrand in the recently established Department of African Literature, headed up by Es’kia Mphahlele. He had completed a drama degree at the University of Cape Town and was working with Benjy Francis at the Afrika Cultural Centre, creating community theatre.

Like everything he did, this work wove together different domains, uncontained by any one realm. In his graduate work, he brought a Black Consciousness lens to white-dominated Marxist revisionism which used class to trump race, and in turn imported his ideas into his theatre-making.

After completing a Masters in the UK, he joined the Department of African Literature at the University of the Witwatersrand in 1988. He soon established himself as a prominent voice in African theatre studies, his scholarship made distinctive by the mix of theory and praxis that he brought to it.

Always deeply interested in those who had come before, he explored the histories of black theatre practice in South Africa, the topic of his PhD and his monograph, Monarchs, Missionaries and African Intellectuals: African Theatre and the Unmaking of Colonial Marginality.

Set between Mariannhill mission in Kwa Zulu-Natal, and Johannesburg, the book explores how a range of figures used theatre practice and debates about drama to negotiate and contest white hegemonies. The volume is due to be republished in August 2021.

The monograph drew on extensive archival labour, and demonstrates Bheki’s talents as an adept archival scholar.

The idea of the archive became an important focus in his thinking, and was informed both by his hands-on experience and his desire to create a substantial archive for teaching and researching the black humanities.

Part of this scholarship is what we might call infrastructural intellectual labour, the painstaking and unglamorous work of making important texts available, producing scholarly editions, writing encyclopedia entries and handbook chapters, editing special issues of journals.

It also involved a dedication to projects that would move black literary traditions from what he called “the anteroom of history”. In all of them he cultivated a meticulous scholarly craft, keeping his head down and doing the work.

A systematic builder, he eschewed the limelight and would have no truck with careerism, academic vanity or posturing. For similar reasons, he was repelled by social media with its speed and superficiality, its dialogue of the deaf.

He, by contrast, was an exceptional listener. For anyone who ever had a serious conversation with him, one will always remember the deep sense of being heard, seen and understood.

His scholarship was likewise a mode of deep listening, a dedicated and respectful attentiveness to what writers and cultural producers were attempting to say.

His intellectual orientations were always broad and generous, looking out to the continent, the diaspora and the world. The bookcases in his office sported two shelves of the African Writers Series, with their unmistakable orange and white spines. Over the course of the 1980s, he had garnered this collection, despite the fact that several titles were banned. He had read them all, one sign of his deep engagement with African literary traditions across the continent.

His knowledge of Caribbean and African American literary and cultural forms was legendary.

He possessed a particular gift for analysing popular cultural forms whether kwaito, popular television, or “swagger in Soweto youth culture”. This emphasis formed part of his unwavering commitment to placing the quotidian and the everyday at the centre of the black humanities. As he explained, he was concerned with:

the lives of ordinary people … in ways that celebrated their knowledge, agency, resilience, hopes, and fears.

In his theatre, film-making and scholarship, he foregrounded their “everyday senses and ways of being that are often ignored, downgraded, or erased by the lenses favoured by parochial and patriarchal nationalists, capitalists, and whiteness in society and culture”. These themes undergirded the Mellon project on Narrative Enquiry for Social Transformation which he co-directed.

Central to his vision of the black humanities was his teaching, mentorship and supervision. A demanding supervisor, he sought to teach graduate students the craft of serious research. At the same time, he was generous with his time, spending hours listening to students, understanding them and their interests.

As a scholar and creative practitioner, he enjoyed a huge international reputation which sought him out, rather than the other way around. There were many awards, prizes and keynote addresses.

He was deeply beloved by those who worked closely with him. We loved his profound wisdom, his brilliance, his amazing wit, his generosity, his integrity, his commitment to equality. We even loved his famously untidy office, his stubbornness, and his determinedly casual dress code – not least his hallmark leather jacket from the 1980s.

It was one of the good fortunes of my life to have worked with him for more than three decades.

Bheki has left us to join the ancestral realm. We now owe him the attentiveness and care that he showed to his literary forebears. We need to think of the intellectual love letters we can write about his work and how we can take his vision for the black humanities forward.![]()

Isabel Hofmeyr, Professor of African Literature, University of the Witwatersrand

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Caroline D. Laurent, Harvard University

Born to a French mother and a Senegalese father, David Diop has won the prestigious annual International Booker prize for translated fiction. He shares the prize with his translator Anna Moschovakis for the novel, At Night All Blood is Black (2018). The book tells the story of a Senegalese soldier who descends into madness while fighting for France in the first world war. It has been a bestseller in France and won several major literary awards. Literature scholar Caroline D. Laurent, a specialist in Francophone post-colonial studies and how history is depicted in art, told us why the novel matters.

Diop is a Franco-Senegalese writer and academic born in Paris in 1966. He was raised in Dakar, Senegal. His father is Senegalese, his mother French and this dual cultural heritage is apparent in his literary works. He studied in France, where he now teaches 18th-century literature.

At Night All Blood is Black is Diop’s second novel: his first – 1889, l’Attraction universelle (2012) – is about a Senegalese delegation at the 1889 universal exhibition in Paris. His next book, about a European traveller to Africa, is set to come out this summer.

Its tells the story of Alfa Ndiaye, a Senegalese tirailleur (infantryman) and the main narrator of the novel (he uses the first-person pronoun ‘I’ in most of the text). He is fighting on France’s side – and on French soil – during World War I.

The novel starts with the narration of a traumatic event that the African soldier has witnessed: the long and painful death of his best friend, Mademba Diop. The traumatic event directs Alfa’s vengeance, that could also be perceived as self-punishment. He kills German soldiers in a similar way, reproducing and repeating the traumatic scene. He then cuts one of their hands off and keeps it with him.

This results in Alfa being sent to a psychiatric hospital where doctors attempt to cure him. It deals with the concepts of war neurosis and shell shock that appeared then (what we now refer to as post-traumatic stress disorder).

The form of the novel associates elements of an inner monologue as well as a testimony. This allows the reader to see, through the perspective of a colonial subject, the horrors of war.

In this sense, Diop writes a nuanced text: he describes the violence perpetrated and experienced by all sides. Alfa Ndiaye becomes a symbol of the ambivalence of war and its destructive power.

It’s important because it addresses what I would refer to as a silenced history: that of France’s colonial troops. Though the colonial troops, and especially the Senegalese tirailleurs, a corps of colonial infantry in the French Army, were established at the end of the 1800s, they became ‘visible’ during World War 1 as they took part in combat on European soil.

Despite this, the involvement of African soldiers during the two World Wars is rarely taught in French schools or discussed in the public sphere. The violence exercised during recruitment in French West Africa, their marginalisation from other troops and the French population notably through a specific language (the français tirailleur) – created to prevent any real communication – and their treatment after the wars go against a specifically French narrative that emphasises the positive aspects of France’s colonialism and its civilising mission.

The lack of visibility of the history of Senegalese tirailleurs is also connected to the ongoing dispute about specific events. One in particular is the massacre of Thiaroye. In December 1944, between 70 to 300 hundred (the numbers are disputed) Senegalese tirailleurs were killed at a demobilisation camp in Thiaroye, after having asked to be paid what they were owed for their military service.

Read more:

The time has come for France to own up to the massacre of its own troops in Senegal

Diop also manages to shatter stereotypes associated with Senegalese tirailleurs. In French historical and literary representations, they are seen as both naïve children in need of guidance and barbaric warriors. Senegalese tirailleurs partook, against their will, in war propaganda: this representation was to create fear on the French side as well as on the German side (Die Schwarze Schande – the Black Shame – presented African soldiers as rapists and beasts).

Diop appropriates this in order to complicate it: while Alfa’s violence in killing his enemies follows this logic, one realises that this causes – and was caused by – great distress. Moreover, Diop also inverts this vision as he questions who is human and inhuman: Alfa asserts that his Captain, Armand, is more barbaric than he is.

Diop thus manages to question representations of black soldiers dictated by colonial stereotypes – in order to dismantle them.

Diop receiving the International Booker prize is of great importance because At Night All Blood is Black exposes a specifically French history that is connected to France’s colonial endeavours. And even though the novel focuses on France, it connects to other histories as it indirectly points to the fact that other European colonial powers also resorted to using colonial troops during wars and erased their role in subsequent commemorations.

The novel also shows the importance and power of translation as Anna Moschovakis has managed to translate all of the beauty and horror of Diop’s prose. In the same way that Diop manages to combine his dual heritage in his text, Moschovakis has allowed English readers to be exposed to a history that is specific to France, and yet similar to other histories.![]()

Caroline D. Laurent, Postdoctoral fellow, Harvard University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

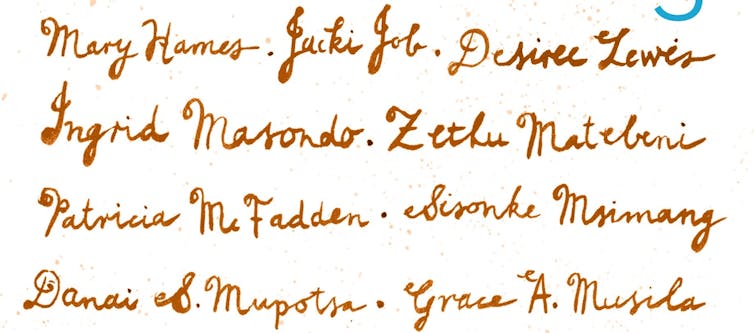

Desiree Lewis, University of the Western Cape and Gabeba Baderoon, Penn State

In the third decade of the new millennium, despite many publishers still seeing black women’s writing as having a limited market, readers have far more access than before to publications by writers from the global South. In particular, the perspectives of black women are certainly more visible in the public domain.

Yet gaps and erasures – based on intellectual authority, financial resources and visibility in the knowledge commons – mean that it’s still easier for work by black, postcolonial and decolonial feminists from global centres to secure publication and wide distribution.

As a result, the growing audience of radical young readers grappling with questions about race, gender, sexuality and freedom in global peripheries often have to turn to critical writing outside their national contexts, which inflect the topics they want to explore. Even for many restless and radical readers in the global North, much remains silenced and absent.

In the new book Surfacing: On Being Black and Feminist in South Africa, South African author Zukiswa Wanner has contributed a piece titled Do I Make You Uncomfortable? about writing in a white publishing industry.

It reminds us that black women writers in South Africa have distinct experiences of being stereotyped. Wanner sums this up in her confrontation with one reviewer who described her work as “chick lit”.

And if black women are the majority in South Africa and I am therefore the standard, shouldn’t it just be called a good book? And I was chick lit versus what? Could she point out to me the male authors in South Africa whose books she’d referred to as ‘cock lit’? Take (JM) Coetzee, with his women characters who aren’t well-rounded and don’t seem to have any agency; was he cock lit?

Surfacing traces a path within black South African feminist thought in 20 dazzling chapters. The collection shows how radical black South African women have been part of several traditions of undocumented intellectual and artistic legacies. In the book Mary Hames recalls, for example, the radical spaces outside conventional classrooms in which she studied banned material during the anti-apartheid struggle.

Our aim as editors was to show how writers in the academy, fiction-writing, journalism and the art world are grappling innovatively with essential topics. Like the politics of self, the complexities of sexual freedoms and identities beyond the blunt frameworks of human rights models. And how to think about “knowledge” more completely and adventurously.

The rich descriptions and interpretations of local realities in Surfacing refine the categories of transnational and black feminism. They bring the breadth of black feminist engagement in the south of the continent into fuller view.

The book is acutely aware of the contrast between the absence of acknowledgement of most black South African women writers and the way certain women, like Khoi historical figure Sara Baartman and activist and politician Winnie Mandela, have been made into global icons. It therefore starts with reflections on them.

Sara Baartman has been exhaustively examined in the north and Winnie Mandela has been the subject of numerous biographical, fictional and non-fictional projects by white scholars.

Intervening into this legacy, author Sisonke Msimang writes an emphatically self-reflexive study which reframes Winnie Mandela. Yet in doing so her interest “was never about ‘cleaning up’ her image or revising facts. It was about recognising that the facts about her required contextualisation.”

Most publications by black South African women are seen as testimonial or fictional. But the contributors of Surfacing seek both to contribute to and to interpret existing bodies of knowledge. In addition, the collection will undoubtedly be remembered for its enthralling writing.

Many chapters take the elastic form of the personal essay. For example, academic and poet Danai S. Mupotsa draws on poetry to talk about experiences of both intimate and public scale. Academic and author Pumla Dineo Gqola pens a playfully serious letter to the South African artist Gabrielle Goliath. And photographer and curator Ingrid Masondo collaboratively authors an essay with the photographers about whom she writes.

In other pieces, academic and author Barbara Boswell recounts her fascinating exchanges with feminist student activists during the #RhodesMustFall protests in her essay about the meanings of pioneering feminist author Miriam Tlali for the present. Academic Grace Musila’s delightful My Two Husbands unfurls the experience of being a brilliant student whose intellectual accomplishment was seen by some men as undermining theirs. Yet within her family her education constituted a cherished and defining achievement.

Read more:

Rest in power, Miriam Tlali: author, enemy of apartheid and feminist

Several chapters in the collection trace the intersections of religion and feminist thinking in South Africa. Academics Sa’diyya Shaikh and Fatima Seedat offer vivid reflections as Muslim feminists on the costs of feminist neglect of the gender of divinity. Dancer, choreographer and academic jackï job’s striking memoir traces a shift from Christian expectations of how to be a “lady” to finding a language in dance for becoming “more than just this body”. And scholar and activist gertrude fester-wicomb recounts her experience as a Christian lesbian anti-apartheid activist of the constrained spaces for queerness during the 1980s.

How to recover histories in the face of reticence is evocatively described by essayist and novelist Panashe Chigumadzi. Through patient listening, she discovers how to hear the language of her grandmother’s silences. In The Music of My Orgasm, anthologist, essayist and poet Makhosazana Xaba movingly testifies to the heritage of feminism she received from her grandfather and her mother. She describes how she learned to cultivate the pleasures of her own body as a force of radical sexual and political liberation.

In their tender relationship to the land on which they grow organic food and medicine, historian and farmer Yvette Abrahams and sociologist and activist Patricia McFadden’s chapters map a visionary future of sharing and abundance.

Throughout the book, it is therefore made clear that foregrounding the positionality of the writer – the social and political contexts that shape their identities – can deepen what is being said.

Who the author is and what perspective she speaks from are in fact integral to her view of the world.

Contrary to advocates of “universality” and “detachment”, this stance seeks to strengthen growing efforts to “surface” the rich diversity of ways of seeing and understanding our world.

Surfacing: On Being Black and Feminist in South Africa is available from Wits University Press![]()

Desiree Lewis, Professor of Gender Studies, University of the Western Cape and Gabeba Baderoon, Associate Professor of Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies and African Studies, Penn State

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.