The link below is to an article reporting on the longlists for the 2021 Indie Book Awards.

For more visit:

https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2020/12/09/160690/indie-book-awards-2021-longlists-announced/

The link below is to an article reporting on the longlists for the 2021 Indie Book Awards.

For more visit:

https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2020/12/09/160690/indie-book-awards-2021-longlists-announced/

The link below is to a Cloud-based book formatting tool called Emper.

For more visit:

https://www.emper.net

The link below is to an article that looks at where you can find a copy of the Gutenberg Bible, as well as an online view.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/gutenberg-bible-online/

Ani Kokobobo, University of Kansas

Nihilism was notably cited during U.S. Senate deliberations after rioting Trump supporters had been cleared from the Capitol.

“Don’t let nihilists become your drug dealers,” exhorted Nebraska Sen. Ben Sasse. “There are some who want to burn it all down. … Don’t let them be your prophets.”

How else to describe the incendiary rhetoric and grievances that Donald Trump has peddled since November? What else to call the denial of the electorate’s will and his deep disdain for American institutions and traditions?

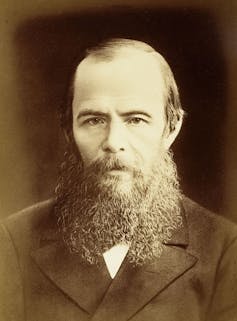

In 2016, I wrote about how Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky had, in his work, explored what happens to society when people who rise to power lack any semblance of ideological or moral convictions and view society as bereft of meaning. I saw eerie similarities with Trump’s actions and rhetoric on the campaign trail.

Fast-forward four years, and I believe the warnings of Dostoevsky – particularly in his most most political novel, “Demons,” published in 1872 – hold truer than ever.

Although set in a sleepy provincial Russian town, “Demons” serves as a broader allegory for how thirst for power in some people, combined with the indifference and disavowal of responsibility by others, amount to a devastating nihilism that consumes society, fostering chaos and costing lives.

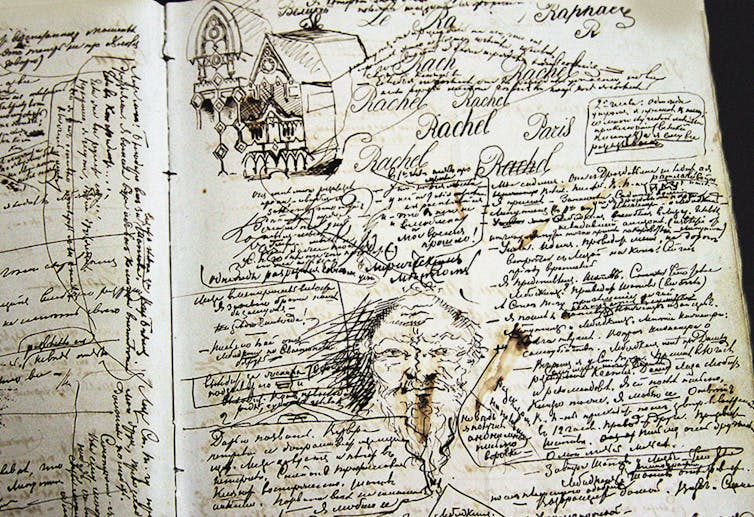

Before “Demons,” Dostoevsky had been writing a novel about faith, “The Life of a Great Sinner.”

But then a disturbing public trial spurred him in a more overtly political direction. A young student had been murdered by members of a revolutionary group, The Organization of the People’s Vengeance, at the behest of their leader, Sergei Nechaev.

Dostoevsky was appalled that politics could be dehumanizing to the point of murder. His focus turned not only to moral questions but also to political demagoguery, which, he argued, if left unchecked, could result in devastating loss of life.

The result was “Demons.” It featured two protagonists: Pyotr Verkhovensky, a former student with no political convictions beyond a lust for power, and Nikolai Stavrogin, a man so morally numb and emotionally detached that he is incapable of purposeful action and stands idly by as violence engulfs his society.

Through these two figures, Dostoevsky tells a broader story about the many flavors of nihilism. Pyotr infiltrates the town’s local social circles, recruits a group of disciples to a revolutionary group and spins lies to band them together so they may do his bidding. Pretending to lead a broad movement of international socialism, Pyotr manipulates those around him into committing violent acts and insurrection against the local government. As a result, one woman is crushed by a mob, a mother and her baby die from chaos and neglect and a fire breaks out that kills multiple others.

Different townspeople espouse multiple and contradictory ideologies; none translates into purposeful action. Instead, they merely leave characters whiplashed and susceptible to being instrumentalized by Pyotor, the master manipulator.

But Pyotr would not prevail without the nihilism of Stavrogin, a local nobleman.

Many townspeople see him as a leader with a strong moral compass. Throughout the novel, Pyotr seeks to loop Stavrogin into his quest for power by either doing him favors that corrupt him or hinting that he will install him as dictator once he successfully carries out a revolution.

On some level, Stavrogin knows better: He should be protecting the town and its people. He ultimately fails to do so, out of sheer despondence and because of the emotional appeal of chaos and violence have for him; they seem to jolt him out of the ennui he often appears to feel.

When given the chance to restrain and turn in to the authorities the escaped convict who perpetrates most of the violence in town, Stavrogin captures him only to eventually let him go. “Steal more, kill more,” he says to a criminal who has already admitted to killing and stealing. Later, when the political climate gets so heated that it seems an insurrection is imminent, he flees town.

In surrendering his responsibility to serve as a moral guardian, Stavrogin becomes complicit in Pyotr’s schemes. He ultimately kills himself – perhaps, in part, out of guilt for his passivity and moral indifference.

Among the two men, Pyotr is the authoritarian figure. And he cleverly insists that members of the revolutionary group break the law together, cementing a loyal brotherhood of criminality.

By contrast, Stavrogin is the novel’s empty center, idly standing by while Pyotr incites violence.

He doesn’t help Pyotr. But he doesn’t stop him, either.

A range of nihilistic justifications – each successively hollower than the rest – seems to have shaped the violence at the U.S. Capitol.

The homegrown American insurrection lacked any sort of ideological foundation. Most ideas fueling it are negations of persons or facts. The immediate rallying cry of the insurrection was the falsehood that the election was stolen. Beyond denying the will of over 80 million people who voted for Joe Biden, this lie also qualifies not as an ideology, but as an absolute denial of truth.

Other ideas fomenting the insurrection – such as “America first” or “MAGA” and even white supremacy itself – are quintessentially founded on the denial of others, whether they are immigrants, foreign nationals or persons of color.

From what we have learned since, some of Trump’s supporters were even imploring him to “cross the Rubicon,” a reference to Julius Caesar’s initiation of the civil war that eventually transformed Rome into a dictatorial empire, expressing a longing to smash American systems and eviscerate the republic.

The only real purpose that seems to have brought the group together was devotion to Donald Trump, who strikes me as the arch-nihilist in all this, the Pyotr Verkhovensky of this American tragedy. Then there are the other public figures who should have known better, who might have helped stop it all, but couldn’t and didn’t. Some, like Stavrogin, excused themselves and were silent for far too long, as the lie about the election grew bigger and bigger. And others seemed to outright encourage the lie through formalized objections in Congress last week.

Playacting at revolution at the behest of a man seeking to cling to power, the rioters ultimately only managed only to vandalize the building, though they left five people dead in their wake.

Nonetheless, to act violently on the basis of such fictions – and to transgress against the humanity of others for nothing at all – is perhaps the most nihilistic act of them all.![]()

Ani Kokobobo, Associate Professor of Russian Literature, University of Kansas

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

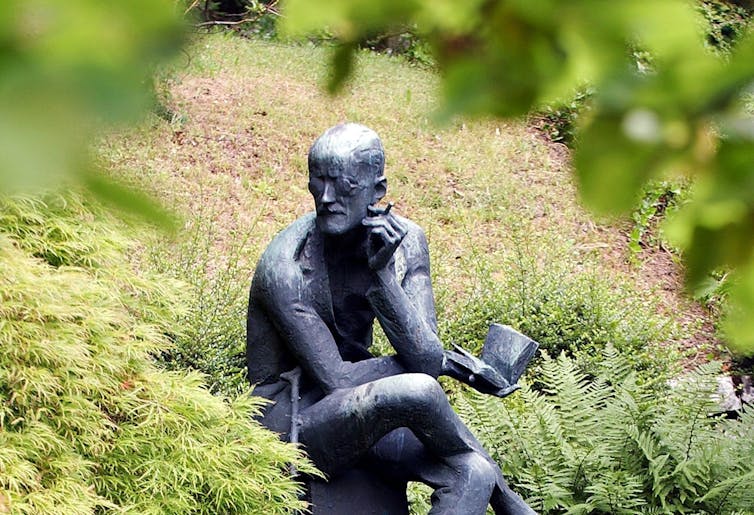

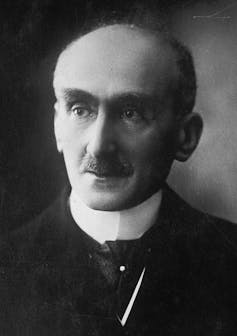

John Scholar, University of Reading

This year marks 80 years since the death of the great Irish writer James Joyce (1882-1941). His most famous novel, Ulysses (1922), is one of those books, like Moby Dick or Infinite Jest, that more people begin than finish. The tome is widely believed to be a stream of consciousness novel and you could certainly be forgiven for thinking that if, like many, you only made it 100 pages or so in.

I often advise against starting at the beginning of the novel. In the case of Ulysses, you are thrown headfirst into the difficult stream of consciousness of Stephen Dedalus, a precocious 22-year-old writer. The fourth chapter, instead, is a much more accessible opening. It too offers a stream of consciousness but an easier sort belonging to the novel’s other main character, Leopold Bloom, a hapless but loveable 38-year-old advertising canvasser. On the day the novel is set, 16 June 1904, Stephen and Bloom strike up an unlikely friendship in Dublin. To read Bloom’s thoughts is to be taken into a stream of sensations, trivia, and wonder.

However, venture further and you’ll discover that Ulysses morphs, becoming instead a great anti-stream of consciousness novel.

For French philosopher Henri Bergson (1859-1941), our stream of consciousness is our continuous sense of time, in which past, present and future merge. It is the fluid life at the heart of our identity. According to Bergson, these streams are at the centre of every object and every person.

Bergson believed we can either “analyse” or “intuit” things or people. When we “analyse” something, we remain outside its stream. We superimpose on its fluid life our own static symbols, like language. Using words means “we do not see the actual things themselves” just “the labels attached to them”.

Another example is numbers. We impose minutes and hours on fluid life. For instance, you can “analyse” a day, breaking it into 24 hours. But to “intuit” it, to see it from within the stream, is to see that time is not so rigid or easily quantifiable – it moves slower when you’re bored or faster when you’re having fun.

In our workaday lives, “analysis” is a necessary shortcut. We need words and numbers, labels and time, to get things done. Artists, according to Bergson, however, have the gift of intuition.

Read more:

A philosophical idea that can help us understand why time is moving slowly during the pandemic

For example, authors’ imaginative use of language makes words a gateway to the streams at the heart of life, rather than distracting labels imposed upon it. Borrowing such ideas, literary critics posited that the stream of consciousness novelist is one who can “intuit” the stream of consciousness of characters and so become them.

Joyce tries for a moment, becomes his characters but soon gets bored with Stephen and Bloom’s streams of consciousness. By the seventh chapter, he begins a long firework display of other styles. Here on, Stephen and Bloom’s streams of consciousness are elbowed out of the way by newspaper headlines, expressionist drama and even romantic fiction. Or they’re shushed by a scientific manual or an encyclopedia of English prose styles.

So Ulysses is a much less consistent stream of consciousness novel than many. But it’s also an anti-stream of consciousness novel as Joyce comically demonstrates his and his characters’ failure to intuit streams.

Joyce enjoys showing us that people are mechanically absent-minded, often because language itself is a mechanism which gets in the way of our efforts to intuit fluid reality.

For example, Stephen, though a creative writer, isn’t at all intuitive. All he can see is the labels attached to things, albeit highly literary labels. When he sees a dog on the beach, his love of words conjures a horse, a hare, a calf, a bear, a wolf, a leopard, a panther and a stag. He can’t focus on the dog.

Bloom’s mechanical behaviour is less literary (words) and more scientific (numbers). True, he is better at intuiting his cat than Stephen is the dog: “Wonder what I look like to her?” he muses, trying to intuit himself into her stream of consciousness. But soon his mind turns to numbers: “Height of a tower? No, she can jump me.” Here he reverts to analysis as he strains to make sense of their difference in height using his human scale, not the cat’s.

Just as Joyce’s characters can’t intuit streams of consciousness, nor can he. He knows that static literary words can’t account for the fluidity of our interiors. Every time he reaches for a new style, in each new chapter, he acknowledges these failures and moves on with glee to the next.

A stream of consciousness does dominate the last chapter. Here we tune into Bloom’s wife Molly’s stream and hear about her afternoon of sex with a colleague. Is this the stream we have been waiting for? Yes and no.

Molly’s thoughts do flow through past, present and future, uninterrupted and unpunctuated. But the Molly we get to know, while charismatic, is something of a static symbol herself, the stock character of the sexually frustrated wife. As we reflect on 80 years since Joyce’s death, Ulysses reminds us that consciousness will always elude the novel but, really, that’s where the fun lies.![]()

John Scholar, Lecturer in the Department of English Literature, University of Reading

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Dan Taylor, The Open University

For most people the latest national lockdown means uncertainty: precarious jobs and incomes, concerns about the safety of loved ones, and – for many parents – the difficulty of combining work with childcare. It also sends us back to a peculiarly confined world unimaginable one year ago – one in which we have come to rely heavily on the internet for work, shopping, leisure and communication with our family and friends. A world where contact with others could have lethal consequences and where venturing outside our homes has become, in some cases, against the law and subject to serious penalties.

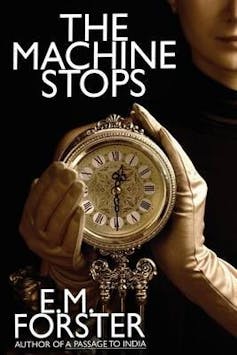

How can literature guide us in this strange new world? E.M. Forster’s short story The Machine Stops (1909) presents an uncannily similar world to our own.

It is set in an unspecified future, where Earth has become inhospitable. Human beings live deep beneath the surface in cramped hexagonal chambers. Each person lives alone, yet on the face of it few are unhappy.

A vast, global Machine connects everyone through video communication – a little like Zoom or WhatsApp which have become so important during lockdown. Each day passes from one virtual meeting or lecture to another, the passage of time indicated only by the dimming of artificial light. People can also mute themselves if they wish (they seem to be untroubled by the “you’re still muted” problem).

An Alexa-like monitor supplies everything they might require at the push of a button:

There were buttons and switches everywhere – buttons to call for food, for music, for clothing. There was the hot-bath button … (t)here was the cold-bath button. There was the button that produced literature, and there were of course the buttons by which she communicated with her friends. The room, though it contained nothing, was in touch with all that she cared for in the world.

The narrative follows the encounter of Vashti and Kuno, a mother and son who live on opposite sides of the world, and their uncomfortable attempt to meet in person at Kuno’s request. Kuno is worried about their helpless reliance on this machine. Some have even come to worship it, lovingly poring the pages of the one book still in circulation, the Book of the Machine, which provides an instantaneous answer to any question (sound familiar?)

For many, like Vashti, leaving home is a terrifying experience. Compared to the Machine’s soothing comforts, sunlight appals. Nature is misshapen. Skin-to-skin contact is shocking and sinister. Vashti swallows mood-numbing medication, (a “tabloid”) to cope with the stress of direct experience. Then one day, Kuno asks: what if the Machine stops?

Bored and disenchanted, Kuno decides to find an exit. In a gesture of romantic if doomed defiance – anticipating that of Bernard Marx and Winston Smith in Aldous Huxley’s 1932 Brave New World and George Orwell’s 1949 Nineteen Eighty-Four – he briefly makes it outside to the surface of the Earth, with its still-beautiful forests, mountains, sunsets, seas – and people. This direct encounter with nature electrifies him.

It is not easy. In a move not unlike dragging yourself out of the house to start a new lockdown exercise regime, he first clambers out of his cosy room but is soon overcome with exhaustion. But he keeps going. Slowly, he climbs up level after level of identical pods, never encountering another person nor meeting any opposition from the Machine (for who would want to leave?)

Finally, he reaches a disused lift shaft to the surface. Outside, he collapses into a grassy hollow, blinded by sunlight for the first time. He discovers there are others out there, the “Homeless”, people who want to think, feel and find meaning in their lives by their own design, without surrendering their freedom to the Machine.

Sensing an escapee, the tentacles of the Machine grab Kuno and pull him back under. But he is transformed. He persuades Vashti to leave her pod and travel around the world to meet him, in person at last, to tell her all about it. Later, when the Machine unexpectedly breaks down, plunging the world into chaos, Kuno and Vashti reunite one last time. If there is hope, Kuno says, it lies in leaving the Machine behind.

The Machine Stops is a reminder of the value of finding a point of escape and enjoyment of the natural world during the tough months ahead. For Kuno, life under the Machine has “robbed us of the sense of space and of the sense of touch, it has blurred every human relation”.

As we look ahead to a time after COVID-19, The Machine Stops asks us to think about how we recover the qualities that make us human. It also asks us to think about the political consequences of long-term reliance on a handful of unaccountable internet platforms, without leaving our homes or interacting with people who might differ in their outlooks to us.

When we cede control in exchange for convenience, cosy echo chambers and comfortingly familiar illusions, bad things follow.

Let’s not overstate all the similarities. Forster’s is a world without work, whereas our machines seem to have us working all hours. Everyone has adequate shelter and food. The problem lies less with the Machine than the masses, willingly distracted by an artificial shadowplay of disinformation and instant gratification.

But these strange and unsettling visions ask of us one thing: what kind of world might we want to live in after the COVID-19 era?

How might we eventually overcome the (understandable) fear of touch? How might we cherish and protect our endangered natural world? How, despite the growing ubiquity of AI and automation, might we bring under control the internet monopolies that attempt to meet our every need and desire and restore the civic, communal and embodied life that preceded it?

One thing is clear: only us human beings, with our messy emotions and complexity, can do that dreaming and that rebuilding together, democratically.![]()

Dan Taylor, Lecturer in Social and Political Thought, The Open University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Alexandra Paddock, University of Oxford and Kirsten Shepherd-Barr, University of Oxford

Like many people, you may have resolved this New Year to read more in 2021 and spend less time on your screens. And now you may be wondering how to find the time to do it, especially in lockdown conditions, with different time constraints and anxieties pressing on us.

One solution is to go with shorter bursts of reading. Our Summer 2020 pop-up project, Ten-Minute Book Club, was a selection of ten excerpts from free literary texts, drawn from a wide range of writing in English globally.

Based on our larger project, LitHits, each week the book club presented a 10-minute excerpt framed by an introduction from an expert in the field and suggestions for free further reading.

We found that the top two things people responded to were the core idea of brevity – one of the most common terms in tweets about the project was “short” – and the quality and diversity of the literature. Our analytics showed that readers dipped in and out of the project over the 10-week span rather than regularly following along. One possible reason for this is that finding regular time for reading literature is not easy, especially right now.

Perhaps surprisingly, then, this article contains no advice about time management or habit-building. Instead, our five tips for reading are about fragments: literature interrupted.

This is nothing new. It is sometimes easy to forget that the 19th-century novel developed by the likes of Charles Dickens, Wilkie Collins, George Eliot and Elizabeth Gaskell, which appear so dauntingly thick in book form, were first read in magazine instalments featuring a chapter or two at a time. Brevity was a significant part of their original appeal.

Begin positively by noticing how much you are already reading in your life without even thinking about it. Even if you have not opened a book in over a year, remember that we are in an age of hyper-literacy and our days are saturated with words. You can harness this.

You probably flex your reading muscles all day long without giving yourself credit for it. Recognising that is a step towards choosing different content, if that’s what you want, or simply considering how you engage with the texts you already read (even if they’re often 280 characters or fewer).

Prioritise the quality of the attention you are paying to words. Reading well is the practice of noticing carefully and with an informed perspective – it’s not so much what you read as how you do it.

Throw away your inner “reading activity tracker” and enjoy curious and provocative engagements with whatever you’re reading, without worrying about racking up the literary miles. This will also dispel that sense of guilt about not reading “enough” that can make reading seem like yet another chore, akin to “not getting enough exercise”.

In his introduction to Sudden Fiction International (1989), an anthology of very short stories or “flash fiction”, American novelist Charles Baxter made the point that the duration of our attention is not as important as its quality: “No-one ever said that sonnets or haikus were evidence of short attention spans.”

As well as not keeping a count of books read, try to note how different the time spent reading feels. Many people assume that reading takes time, the very thing most of us lack. Yet there is another, more subtle temporal element to reading that has more to do with the cognitive experience of the text itself.

Centuries can flash by in seconds and moments can roll out over aeons. Jia Tolentino captures this brilliantly in her characterisation of reading the work of Margaret Atwood: “nothing was really happening, but I was riveted, and fearful, as if someone were showing me footage of a car crash one frame at a time”.

You can find pleasure in a few snatched moments of reading, and these are just as worthwhile for the immersive experience they bring through the encounter with language, images, and ideas. There is no ideal environment or place to read – just do it wherever you can and whenever you have some spare moments.

Choose what you read and find ways to try texts out for yourself to help your search, rather than relying on recommendation sites. Such sites are usually not as objective as they claim. For instance Goodreads, the social site where people can compile books they’ve read or would like to read, as well as find recommendations, is owned by book-selling behemoth Amazon.

Recognise, too, the difference between buying a book and reading more. In her 2019 book, What We Talk about When We Talk about Books, Leah Price emphasises that every reader finds the text through their own journey, in the conversations, forums and different devices that could have brought them to it.

Rita Felski too, in Uses of Literature, talks about the ways that texts need to connect with us, and “make friends” – surviving history necessarily because they make connections with people again and again.

So, will you be reading more in 2021? Reader, you already are.![]()

Alexandra Paddock, Lecturer in English and Assistant Senior Tutor, University of Oxford and Kirsten Shepherd-Barr, Professor of English and Theatre Studies, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Alfonso Martín Jiménez, Universidad de Valladolid

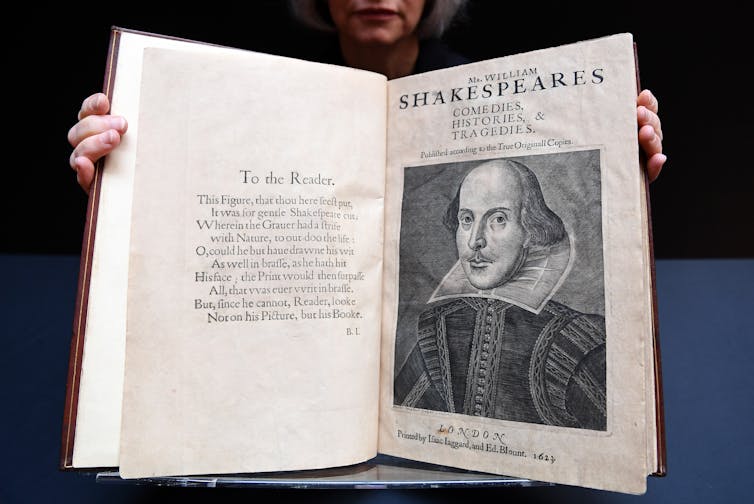

William Shakespeare and Miguel de Cervantes, two of the most important writers of literature, are surrounded by a halo of mystery related to authorship.

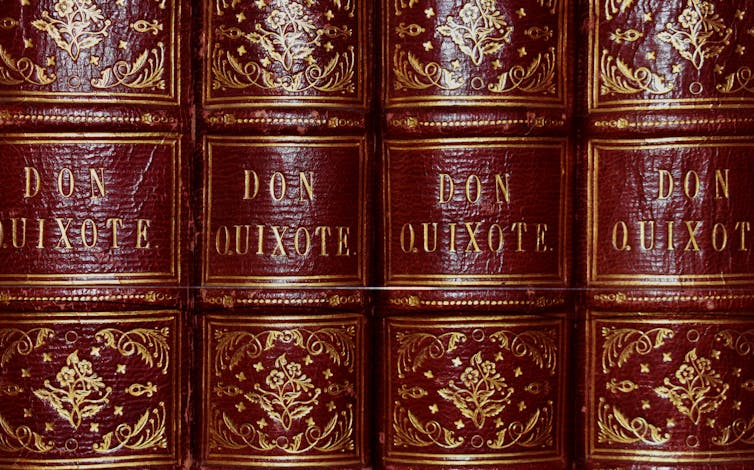

In the case of Shakespeare, the question of whether he is the true author of his plays has circulated for some time. In the case of Cervantes, mysteries about authorship tend to concern who wrote the sequel to the first part of Don Quixote, one of the earliest modern novels.

Cervantes published the first part of Don Quixote in 1605. In 1614, an unofficial sequel by the pseudonymous Alonso Fernández de Avellaneda was published. In response, a year later, Cervantes published his sequel to Don Quixote, denouncing Avellaneda’s version in the prologue. Since then, Avellaneda’s identity has become the greatest mystery in Spanish literature.

Both Cervantes and Shakespeare lived and died at around the same time. Shakespeare was born into a wealthy, rural family and Cervantes had humbler origins, yet both had a passion for the theatre and wrote plays.

In both cases, we hardly know anything about their childhoods and education (although it is known that neither went to university).

Great authors lend themselves to speculation. Shakespeare’s lack of education is one of the main arguments against the idea that he wrote his works, which have been attributed to 80 different authors. While Cervantes’ authorship tends not to be under the same scrutiny, questions about who exactly Alonso Fernández de Avellaneda was, remain.

Cervantes’ own educational background, however, suggests that it is possible to write to a high standard without academic training. If this could be true for the Spanish writer, why not for Shakespeare too?

A very large number of authors have also been proposed as candidates for the authorship of Avellaneda’s sequel to Don Quixote.

Social and cultural prejudices have been important in both cases. Shakespeare’s works show a detailed knowledge of the highest social classes, which is why it is thought that they should have been composed by some illustrious person of the time, such as Sir Francis Bacon.

However, Cervantes also had knowledge of the higher social classes and did not belong to them. Some researchers have even proposed that Avellaneda could have been Lope de Vega, the most prominent Spanish playwright at the time, since it is more attractive to imagine Cervantes confronted with a great author than with a mediocre person.

In both cases, figures who died well before both Shakespeare and Cervantes have been proposed as authors: Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford as the author of Shakespeare’s plays, and the Spanish writer Pedro Liñán de Riaza as Avellaneda, the unconvincing argument being that their works were left incomplete and were finished by other writers.

That said, it’s important to look at other plausible explanations. At the time of the publication of the first part of Don Quixote, there were no copyright laws protecting writers from continuations or plagiarism of works, which explains how Avellaneda’s version came to be.

Similar confusion has been caused in Shakespeare’s case. The Taming of the Shrew had an earlier anonymous version titled: The Taming of a Shrew, seemingly supporting theories that Shakespeare’s version was co-authored, or written by someone else entirely.

These days, however, following a theory put forward by Shakespearean scholar Peter Alexander in 1926, it is generally accepted that The Taming of A Shrew was simply an attempt to record the live production version of the play from memory.

In the case of Cervantes, I think I have cleared the mystery: we already know what Cervantes thought about Avellaneda’s identity, which should put an end to absurd speculation.

As one popular theory goes, Avellaneda’s sequel to Don Quixote should be read as an embittered response to Cervantes’ parody of two real people: Lope de Vega and Jerónimo de Pasamonte. Pasamonte was a soldier from the region of Aragon who took part – as did Cervantes – in the battle of Lepanto (1571). Cervantes is said to have behaved heroically in the battle since, despite being ill, he insisted on fighting and was wounded several times.

Shortly afterwards, in 1574, Pasamonte was taken prisoner and spent 18 years in captivity. Upon his release, he returned to Spain and finished his autobiography, Life and Works.

When writing about the capture in 1573 of La Goleta (where there was in fact no actual battle), Pasamonte claimed to have acted as heroically as Cervantes at the battle of Lepanto.

After seeing how Pasamonte had usurped his heroic deeds in his autobiography, Cervantes satirised it in the first part of Don Quixote. Cervantes turned Jerónimo de Pasamonte into Ginés de Pasamonte, a galley slave, who is presented as a liar, a cheat, a coward and a thief, and is gravely insulted by characters Don Quixote and Sancho Panza.

The hypothesis that Pasamonte was Avellaneda, proposed by Martín de Riquer, an academic at the Royal Spanish Academy of the Language, is increasingly accepted.

As I have probed in my book, “The two second parts of Don Quixote”, Pasamonte sought to take revenge on Cervantes, writing a sequel to Don Quixote with the intention of robbing Cervantes of his earnings from the second part. In order not to be linked to Cervantes’ galley slave, he then signed it under a pseudonym.

To get revenge on Avellaneda, Cervantes imitated his imitator and created a masterly scene, making the literary representation of Avellaneda (personified in a character known as Jerónimo) recognise his Don Quixote as the true one.

As attractive as speculation about Shakespeare and Cervantes’ authorship may be, looking closer at their lives shows just how irrelevant class, education and conspiracy theories are in terms of explaining their genius.![]()

Alfonso Martín Jiménez, Catedrático de Teoría de la Literatura y Literatura Comparada, Universidad de Valladolid

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

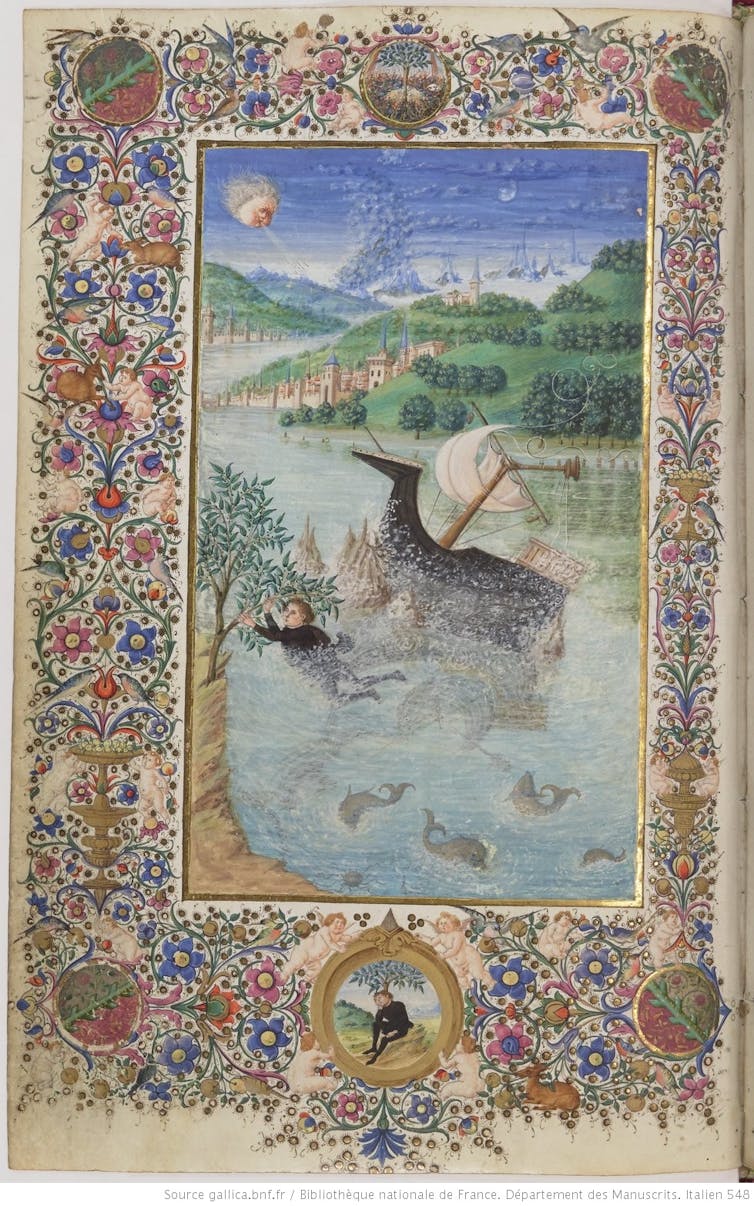

Maria Clotilde Camboni, University of Oxford

Imagine a world where we knew the name of Homer, but the poetry of The Odyssey was lost to us. That was the world of the early Italian Renaissance during the second half of the 15th century.

Many people knew the names of some early poets of Italian literature – those who were active during the 13th century. But they could not read their poems because they had not been printed and were not circulating in manuscripts.

Then, in around 1477 the de facto sovereign of Florence, Lorenzo de’ Medici – “the Magnificent” – commissioned the creation of an anthology of rare early Italian poetry to be sent to Federico d’Aragona, son of the king of Naples.

The luxurious manuscript became one of Federico’s most prized possessions. It was exhibited to and coveted by patricians and intellectuals for half a century – until its disappearance in the early 16th century.

But it did not disappear completely. The interest aroused by this manuscript generated a paper trail of letters, partial copies and other materials which I, along with other researchers, have managed to piece together. These documents allow us to reconstruct not only the trajectory of the manuscript through different courts in Europe, but – crucially – what works it may have contained.

Vernacular literature – that is, literature written in the language normally spoken by the people – only had a marginal role during the Middle Ages and early Renaissance. The “real” culture was Latin. This meant that interest in the early poets who wrote in the Italian vernacular was limited – until the flourishing of the Italian language in the age of Lorenzo de’ Medici.

One of these 13th-century poets, Cino da Pistoia, was loved and celebrated by Dante Alighieri in his treatise on the art of poetry, “De vulgari eloquentia”. Dante said of his contemporary Cino:

There are a few, I feel, who have understood the excellence of the vernacular: these include Guido, Lapo … and Cino, from Pistoia, whom I place unworthily here at the end, moved by a consideration that is far from unworthy.

Guido Cavalcanti was another love poet. He and Dante were best friends and Dante regarded Cavalcanti as an authority on poetry. Cavalcanti is mentioned in Dante’s early poetry collection, the Vita nova.

The whole work is addressed to Cavalcanti and Dante even implies that he is writing in Italian because of him. But despite Dante’s popularity, even the Vita nova was hard to get hold of before 1576 when it was printed for the first time.

Guittone d’Arezzo was another highly regarded poet. He started as a love poet before becoming the most important author (before Dante) writing on moral and political themes.

The collection of Tuscan poetry sent to Federico d’Aragona by Lorenzo de’ Medici in 1477 contained Dante’s Vita nova, as well as rare poems recovered from ancient manuscripts by Cino, Guittone, Cavalcanti and many others. The collection was opened by a letter signed by Lorenzo himself.

The manuscript was later named after its owner and became the Raccolta Aragonese (“the Aragon collection”). It became one of Federico’s most prized possessions and the object of widespread interest and curiosity.

Federico took it with him when he travelled to Rome at the end of 1492 to swear allegiance to the Borgia Pope Alexander VI. During this trip, he showed it to the scholar Paolo Cortesi, who immediately wrote to Piero de’ Medici – the son of the recently deceased Lorenzo the Magnificent. In this letter, Cortesi recounts that he had been shown a manuscript with poems by early vernacular poets, chiefly Cino and Guittone. The excitement is palpable: Cortesi is able to read poems by these authors whose names he had only ever heard mentioned before.

Such was the interest in these lost poets that partial copies of the Raccolta started to circulate. The first one was probably made by someone in Federico’s inner circle before he became King of Naples in 1496. News about his collection of rare early Italian poems was spreading.

Federico was the last sovereign of his dynasty. He lost his throne when Louis XII of France invaded Italy. When he left Naples in the summer of 1501, Federico took the books of the royal library with him. He later had to sell part of them to sustain himself and his followers during his exile in France. But the Raccolta Aragonese was not sold and after his death in 1504 it was passed on to his widow, Isabella del Balzo.

The widow queen then lent the collection to Isabella d’Este, the Duchess of Mantua, in northern Italy, in 1512. She kept it for two months and, even though in her letters she promised not to leave it in other people’s hands, it is likely that she commissioned a complete copy which led to further partial copies being made.

Even though the transmission of these copies was in manuscript form – and so not widespread – several Renaissance intellectuals managed to read these “lost” works and were influenced by them in their attempts to reconstruct the history of Italian literature.

The real game-changer came in 1527 when a printed collection of vernacular poetry finally took the works of masters like Cino, Guittone and Cavalcanti to a much wider audience. This is when they stopped being obscure and arcane authors and finally took their place in the canon of Italian literature.![]()

Maria Clotilde Camboni, , University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The links below are to articles reporting on the increase in storage space for entry level Kindles.

For more visit:

– https://goodereader.com/blog/electronic-readers/amazon-kindle-now-has-8gb-of-storage-instead-of-4gb

– https://blog.the-ebook-reader.com/2020/11/30/kindle-now-comes-with-double-the-storage-space/

You must be logged in to post a comment.