The link below is to an article reporting on a surge in reading during the current Coronavirus pandemic.

For more visit:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/may/15/research-reading-books-surged-lockdown-thrillers-crime

The link below is to an article reporting on a surge in reading during the current Coronavirus pandemic.

For more visit:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/may/15/research-reading-books-surged-lockdown-thrillers-crime

The link below is to an article reporting on the longlist for the 2020 Miles Franklin Literary Award.

For more visit:

https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2020/05/12/150363/miles-franklin-literary-award-2020-longlist-announced/

The link below is to an article reporting on the longlist for the 2020 Peter Carey Short Story Award.

For more visit:

https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2020/05/14/150542/peter-carey-short-story-award-2020-longlist-announced/

Lucy Whitehead, Cardiff University

When Charles Dickens died on June 9 1870, newspapers on both sides of the Atlantic framed his loss as an event of national and international mourning. They pointed to the fictional characters Dickens had created as a key part of his artistic legacy, writing how “we have laughed with Sam Weller, with Mrs. Nickleby, with Sairey Gamp, with Micawber”. Dickens himself had already featured as the subject of one piece of short biographical fiction published during his lifetime. Yet, in the years following his death, he would be increasingly appropriated as a fictional character by the Victorians, both in published texts and in privately circulated fan works.

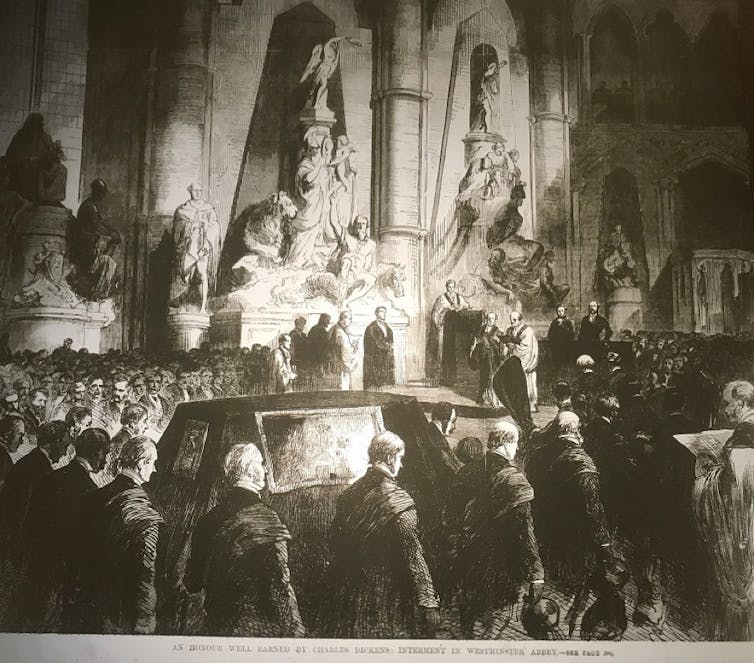

Dickens’s private family funeral at Westminster Abbey created a gap in knowledge which some journalists chose to fill with a fictional scene they considered more emotionally satisfying. The London Penny Illustrated Paper visually re-imagined the funeral, publishing a large illustration depicting a crowded public event.

Under the sub-heading: “A National Honour Due to Charles Dickens”, the accompanying text acknowledges that the image is fictional, but argues that:

A ceremony such as is depicted in our Engraving would unquestionably have best represented the national feeling of mourning occasioned by the lamented death.

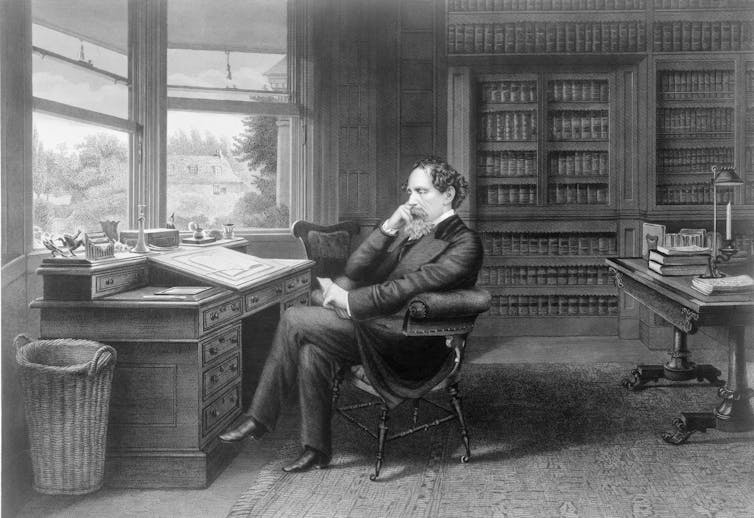

It was the publication of John Forster’s Life of Charles Dickens in 1872–74, though, that marked a watershed in fictionalisations of Dickens. Victorian readers now had a full-length birth-to-death Dickens biography to draw on, written by a friend who had known him for his entire adulthood. Dickens’s Preface to his 1849–50 novel David Copperfield had encouraged readers to interpret it as semi-autobiographical. However, it was only with Forster’s biography that the full extent of the similarities between Dickens and the fictional Copperfield was made public.

The revelation that Dickens had performed child labour in a blacking warehouse when his father was imprisoned for debt, before rising to international fame in his twenties, gave him a life story that the press described as rivalling Dickens’s “most popular novel”.

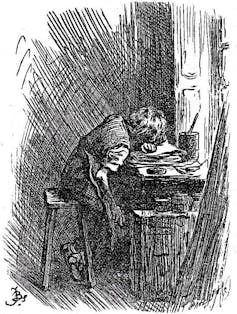

The Household Edition of Forster’s Life, published by Chapman & Hall in 1879, included 28 new illustrations of the biography by Fred Barnard. Among them was an emotive image of Dickens as a young boy in the blacking warehouse.

Dickens wrote a private account of this time, for which Forster’s biography is our only remaining source. In this autobiographical fragment, Dickens describes how he was brought down to work among other boys in the warehouse. He was careful not to let them see his suffering, and to make sure that he worked as hard as them. Yet what Barnard pictures is a scene of solitude, visible despair or perhaps exhaustion at the warehouse that is not described in this fragment. The image bears a closer resemblance to Dickens’s fictionalisation of the first day at the warehouse in David Copperfield.

In the novel, the young Copperfield writes that: “I mingled my tears with the water in which I was washing the [blacking] bottles.” Barnard heightens and externalises the private emotion that Dickens wrote about in the autobiographical fragment to create a fictional scene. In doing so, he further blurs the boundaries between Dickens and the fictional Copperfield.

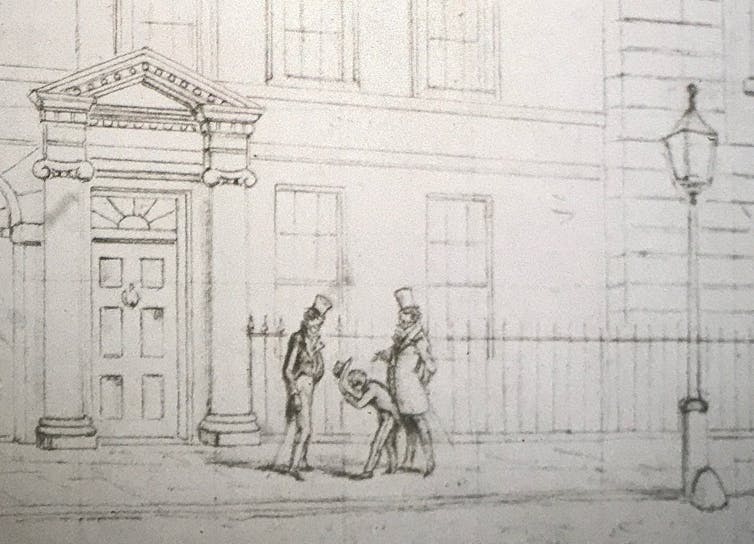

The practice of Grangerization – the art of extending and customising a published book with inserted material – was popular among Victorian readers. Additional fictionalised illustrations of Dickens’s life, created by the Dickens illustrator Frederick W. Pailthorpe, are revealed in a 14-volume Grangerization of Forster’s Life, held in the British Library.

Some of these seem to have been created for personal interest and private circulation among fellow Dickens enthusiasts, rather than for publication. One sketch shows Dickens as a boy making a low bow to a friend of his father’s.

This image is based on an incident which Forster describes as taking place at the blacking warehouse where Dickens worked. Yet Pailthorpe’s illustration fictionalises the location of the event, transposing the young Dickens to the front of the house of John Dryden, the former poet laureate next to whom Dickens would eventually be buried in Westminster Abbey. In doing so, Pailthorpe creates a narrative in which Dickens was always destined for literary greatness.

In the 21st century, readers have commented on the resemblances between the fictional stories which the young Brontë siblings wrote about real-life contemporary figures such as the Duke of Wellington, and 20th and 21st-century forms of fan fiction. Oscar Wilde’s 1889 story, The Portrait of Mr W.H., focuses on a series of men whose biographical speculations about the life of Shakespeare verge on fictionalisation.

Nevertheless, recent scholarly work on biographical fiction has described it as coming into being “mainly in the 20th century”. Press articles on the form of fan fiction known as “real person fiction” have largely focused on it as a product of internet culture (while noting briefly that many of Shakespeare’s plays also fictionalise real-life figures).

Archival work on the Victorian press, and on semi-private forms of reader response such as Grangerized books, can flesh out our understanding of the role that biographical fictionalisation played in Victorian culture. It demonstrates a longer and more varied history of the human desire to appropriate and imaginatively recreate famous contemporary figures. And it shows that part of Dickens’s creative legacy, as well as his own works, was the fictional forms that his life inspired others to create.![]()

Lucy Whitehead, PhD researcher, School of English, Communication and Philosophy, Cardiff University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Lords of the Horizons A History of the Ottoman Empire by Jason Goodwin

Lords of the Horizons A History of the Ottoman Empire by Jason Goodwin

My rating: 2 of 5 stars

Unfortunately this book did not realise my expectations for it. That is perhaps the kindest way I can put it. I was hoping for a reasonably detailed chronological history of the Ottoman Empire, it rise and demise. There is a lot in this book, plenty of interesting detail and some amusing also. However, it is a little … too confusing for my like. It is all over the shop at times and just doesn’t ‘fit together’ enough for me. It is a useful read, but I doubt it will leave a lasting impression on me or an understanding of the Ottoman Empire with me.

Leon Litvack, Queen’s University Belfast

This episode of The Conversation’s In Depth Out Loud podcast, features the work of Leon Litvack at Queen’s University Belfast, a world authority on Charles Dickens, on what happened after the death of the author.

His new research has uncovered the never-before-explored areas of the great author’s sudden death on June 9 1870, and his subsequent burial.

Dickens’s death created an early predicament for his family. Where was he to be buried? Near his home (as he would have wished) or in that great public pantheon, Poet’s Corner in Westminster Abbey (which was clearly against his wishes)? But two ambitious men put their own interests ahead of the great writer and his family in an act of institutionally-sanctioned bodysnatching.

You can read the text version of this in depth article here. The audio version is read by Michael Parker and edited by Gemma Ware.

This story came out of a project at The Conversation called Insights. Sponsored by Research England, our Insights team generate in depth articles derived from interdisciplinary research. You can read their stories here, or subscribe to In Depth Out Loud to listen to more of their articles in the coming months.

The music in In Depth Out Loud is Night Caves, by Lee Rosevere.

Leon Litvack, Associate Professor, Queen’s University Belfast

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

David Amigoni, Keele University

Charles Dickens’ first biographer, John Forster, ended The Life of Charles Dickens in 1874 with the Dean of Westminster’s sermon. This was delivered in Westminster Abbey on June 19 1870, three days after the novelist’s funeral. Dickens’s grave in Poets’ Corner would, said the dean:

henceforward be a sacred one with both the new world and the old, as that of the representative of literature, not of this island only, but of all who speak our English tongue.

In the century and half since his death, writers from the southern hemisphere have continued to recast Dickens’s fictions in new forms. Two novels – Peter Carey’s Jack Maggs (1997) and Lloyd Jones’s Mr Pip (2007) – rework Dickens’s Great Expectations (1859-60).

In so doing, they present readers with opportunities to rethink ways in which Dickens was “a representative of literature”; including the power relations around class and colonialism that have shaped the transmission of writing in “our English tongue” for the past two centuries.

In Jack Maggs, Carey – a double Booker Prize-winning Australian novelist – rewrites Great Expectations from the perspective of a convict who returns from his sentence in the new world to terrible risk: the only sure thing that old England can offer him is a noose. Dickens’s original novel sees the world from the shifting perspective of Philip Pirrip – or “Pip” – an orphan boy plucked from obscurity who thinks he has been “made” by the wealthy Miss Havisham. In fact his fortunes have been advanced by Abel Magwitch, a convict who the young Pip had helped in an escape bid.

In Carey’s pastiche, Magwitch becomes Jack Maggs, who has survived transportation to Australia and become a successful and wealthy brickmaker. He returns from the British colony of New South Wales to the London of 1837, the year during which Dickens rose to fame. Maggs wants contact with Pip – rendered here as the young man Henry Phipps, whom he has made into a gentleman.

Instead, he encounters the young, upwardly mobile novelist Tobias Oates: ambitious, anxious to hold onto the new respectability he has secured after childhood poverty, and riddled with emotional and financial insecurities. Oates is of course a version of the young Dickens prior to the consolidated public image of the respectable literary giant commemorated in Forster’s biographical portrait.

Carey reminds us, through Oates, that the Dickens of 1830s closely observed a London world of crime and sexual misdemeanour that could scarcely be rendered in the language of fiction available to him. Dickens also flirted with the new science of mesmerism, a technique which Oates applies to Maggs to exorcise him of the “phantoms” or traumas of brutalised convict life. Oates thereby appropriates Maggs’s story as a series of “burgled secrets” which are to be recast as a crime melodrama for his own literary gain.

Yet Carey reverses this invasive power relation and enables Maggs to tell his own story, restoring him to his own emotionally scarred but resilient origins. Carey concludes with the image of Maggs as redeemed Australian subject who has exorcised the phantoms of English class longings, and is restored to his family in the new world.

Lloyd Jones’s Mr Pip transports Great Expectations to the Pacific, the conflicted island of Bouganville in Papua New Guinea. The New Zealand novelist writes about the reading and interpretation of Dickens’s novel among a group of black children and their eccentric, self-appointed white teacher, Mr Watts, as an event punctuated by the rebel insurgence, military occupation and horrific violence experienced in the 1990s.

If Dickens wrote Great Expectations as a tale of betrayal, guilt and ambiguous origins in 1860, Jones’s novel shows how that moral and emotional frame can be adapted to new, post-colonial conditions. Matilda is Jones’s 14 year-old fatherless narrator, who comes to appreciate that Pip’s story of mobility and self remaking, which the migrant Mr Watts reads to his pupils as a source of inspiration, is powerfully apt for those whose lives are subject to displacement and migration.

But the “Pip” that Matilda venerates by writing his name, in shells, on the beach is mistaken by military occupiers as the name of a rebel who is being concealed by the villagers. In a terrible unfolding of misunderstandings, both Matilda’s mother and Mr Watts are butchered.

As Matilda escapes to a life of education and possibility, reunited with her migrant father in Australia, she comes to realise that the Great Expecations that Mr Watts read to them was in fact an abridged format for the children of empire: that Dickens’s “sacred” text existed in multiple versions.

Jones’s story casts powerful new light on the way in which Dickens can be seen as a leading “representative of literature”. In one sense, Dickens was the great author of Forster’s biography, buried in Poet’s Corner. In another, as Matilda comes to recognise, the name “Dickens” helped to drive and commodify the global transmission of Victorian literature in many different formats to many new parts of the globe.

As Regenia Gagnier’s research on the global circulation of Dickens and other Victorians shows, literature itself is always in a process of migration to and through new power relations.![]()

David Amigoni, Professor of Victorian Literature, Pro Vice-Chancellor for Research and Enterprise, Keele University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Brigid Magner, RMIT University

The Black Summer bushfires may have ended, but the cultural cost has yet to be counted.

Thousands of Aboriginal sites were likely destroyed in the 2019 bushfires. But at present, there is no clarity about the numbers of precious artefacts lost.

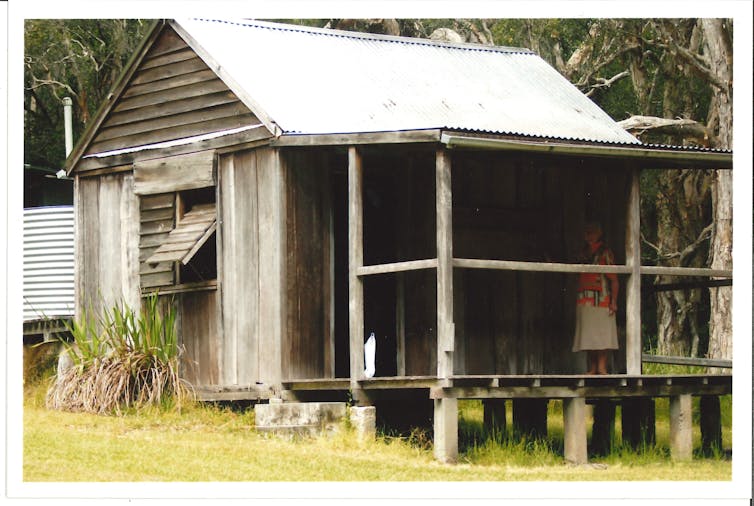

Though recent by comparison, relics from Australian literary heritage have also been reduced to ash. Last year’s bushfires destroyed a hut built specially for author Kylie Tennant (1912–1988) at Diamond Head, and many High Country huts associated with A.B “Banjo” Paterson’s The Man From Snowy River.

Thankfully, NSW Parks and Wildlife Service are making plans to rebuild Kylie Tennant’s hut. But after this devastating loss, it’s impossible to ever fully recreate the authentic atmosphere of Tennant’s writing retreat.

Tennant was best known for her social realist studies of working-class life from the 1930s, including her Depression novels The Battlers (1941) and Ride on Stranger (1943).

During the second world war, Tennant moved to Laurieton with her husband and their daughter Benison, and lived there until 1953. At nearby Diamond Head, she met Ernie Metcalfe, a returned serviceman from the first world war and well-known local bushman.

Read more:

Reading three great southern lands: from the outback to the pampa and the karoo

Metcalfe felt Tennant had paid him too much for the land she bought from him, which was partly why he offered to build the hut. Bill Boyd, who later restored the hut, remembers

Kylie would insist on paying him […] she only paid him about 25 pounds which was a lot of money in that time.

Metcalfe was memorialised in her non-fiction book The Man on the Headland (1971). From the beginning, fire played a part in the hut’s life.

The first summer, as though Dimandead [Diamond Head] had made a sudden bid against this new invasion, a fire leapt the creek and came so close to the house that one window cracked in the heat.

Ernie fought the fire single-handed and when we arrived he was standing sooty with ash in his beard in a blackened desert with the house safe in the middle.

While appearing to be an ordinary bushman’s dwelling, “the romance” of Kylie’s Hut was “undeniable”, according to Andrew Marshall, a marine wildlife project officer in the NSW Parks and Wildlife Service. It’s fondly remembered by locals, tourists and aspiring writers who have visited since the 1980s.

Its location in a campground was unique because it quietly coexisted with holidaymakers rather than being relegated to a specially demarcated, curated space. However, this lack of protection left it exposed to the elements and the predations of climate change.

Read more:

‘Like volcanoes on the ranges’: how Australian bushfire writing has changed with the climate

In 1976, Tennant donated the hut and the surrounding land to Crowdy Bay National Park, partly to try to protect the environment from ongoing rutile mining.

The creation of the Crowdy Bay National Park was facilitated not only by Tennant’s gift, but also by the earlier dispossession of the Birpai peoples and the re-zoning of their land.

It’s also important to acknowledge Tennant’s tendency to erase the Indigenous presence in this book. In the opening chapter, Tennant writes that Diamond Head’s “aborigines were gone, all gone, like the smoke blown from their fires”.

The erroneous belief that previous inhabitants had “disappeared”, meant the story of Tennant and Metcalfe’s friendship, symbolised by the hut, effectively obscured earlier stories of the Traditional Owners.

Local bush carpenter Bill Boyd substantially refurbished Kylie’s Hut in the early 1980s. A master of old forestry and timber working tools, Boyd used the restoration of Kylie’s Hut as a way to share his knowledge of the uses of broad-axe and adze (an axe-like tool with an arched blade).

Aside from its association with Tennant, the hut has additional significance because it was built using “unpretentious construction techniques” and displays “a unity of form, design and scale”, according to Libby Jude, a ranger from the NSW Parks and Wildlife Service.

It was composed of “strong, natural textures” associated with the fabric of the place in which it stood. And the specialised restoration methods Boyd used are heritage practices that are themselves worthy of preservation.

Boyd also passed on his knowledge to younger carpenters while restoring many of the High Country huts, some dating back to the 1860s and associated with The Man From Snowy River. Most of these were also razed by the recent bushfires.

Members of the Kosciuszko Huts Association have expressed their desire to restore the huts, but a conversation about when and how they could be reconstructed will be well down the track.

Unlike the United Kingdom, where literary properties are routinely listed on maps, Australia tends not to proudly celebrate sites related to its writers.

Aside from the work done by the National Trust, literary societies and enthusiasts in regional communities mostly drive the protection of Australian literary sites.

Read more:

Ten of Australia’s best literary comics

Ideally, there should be a more coordinated approach to our literary heritage which could identify vulnerable structures and take steps to ensure that, wherever possible, they’re not wiped out by natural and man-made disasters.

The memorialisation of Kylie’s Hut, which began in the 1980s as a response to her book The Man on the Headland, rendered black history peripheral to the central story of bushmen like Metcalfe living in the area. Nevertheless, it was an accessible literary site stimulating awareness of aspects of our cultural history, which might otherwise remain almost completely unknown.![]()

Brigid Magner, Senior Lecturer in Literary Studies, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article reporting on the winners of the 2020 Hans Christian Andersen Award.

For more visit:

https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2020/05/12/150339/woodson-albertine-win-2020-hans-christian-andersen-award/

You must be logged in to post a comment.