Wikimedia Commons

Brigid Maher, La Trobe University

In our series, Guide to the classics, experts explain key works of literature.

Many young children have flirted with the notion of escaping, once and for all, those stifling rules and obligations invoked at dinnertime: eat your greens, finish everything on your plate…

Few (thankfully) will have the kind of commitment required to take this rebellion to the extremes of Cosimo Piovasco di Rondò, protagonist of Italo Calvino’s enchanting novel, The Baron in the Trees.

The meal in question is indeed stomach-turning: snail soup followed by a main course of snails.

But when, one momentous day in 1767, the 12-year-old Cosimo pushes away his plate and refuses to touch his food, no admonitions from his appalled parents will change the boy’s mind. He runs from the family home and climbs a large holm oak on their estate, never again to come down to earth.

Calvino wrote the novel in 1957, and it remains one of his most loved. The story of Cosimo’s astonishing existence among the trees, where he lives through to adulthood and old age, during times of great turmoil, combines the bizarre imaginative flair of a folktale with a profound meditation on questions of isolation and human interaction.

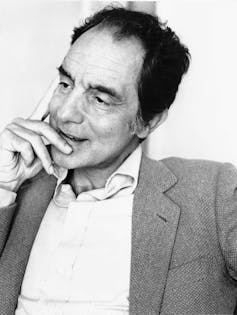

The man behind the novel

Calvino was born in Cuba in 1923 to Italian parents who were working there as scientists, but the family moved back to Italy just two years later. His childhood was spent in the small coastal city of Sanremo (Liguria) on the Italian Riviera, very close to the French border.

The landscape of Liguria – in an imagined and idealised form that has since been lost to development – forms the luxuriant setting for Cosimo’s arboreal adventures.

Shutterstock

The baron’s (fictional) village of Ombrosa is rich in vegetation, and trees of every kind – oaks and mulberry trees, magnolias and Indian chestnuts, pines and olives – become Cosimo’s kingdom.

The important link to the environment

Life in the treetops is not without its challenges. Part of the charm of the novel lies in the way Calvino is able to use allegory to explore the human condition, without sidestepping a depiction of how Cosimo manages the practicalities of his peculiar existence.

Many of the funniest moments lie in Cosimo’s ingenuity and determination as he makes himself a permanent, and surprisingly comfortable, home in the trees. Hunting polecats and badgers affords him the fur jacket, hat and leather shoes required for spending cold winters out in the elements, while also lending him an eccentric appearance that little befits a baron.

Yet his life is nothing if not civilised. He comes up with strategies for washing, cooking and toileting; he can access drinking water, and even trains a goat to climb a short way up an olive tree so he can reach down to milk it.

But Cosimo’s day-to-day existence is not focused solely on surviving in his new habitat. He engages in many intellectual pursuits, becoming an avid reader of literature and philosophy. When he befriends the brigand Gian dei Brughi, on the run from the law, the two share this passion for books and soon, procuring reading material for the fugitive is almost a full-time job for Cosimo.

This love of the written word ultimately proves to be Gian dei Brughi’s undoing. He begins to neglect his brigandage and loses all fascination in the eyes of the local people.

When the once-elusive dei Brughi is finally captured, it is because he is too desperate to get back to his novel (Richardson’s Clarissa) to successfully carry out a burglary, and his erstwhile accomplices hand him over to the authorities.

Wikimedia Commons

Cosimo, by contrast, has a greater capacity for balance. His extreme rebellion against the strictures of his noble upbringing is never an outright rejection of society or community. He is an eccentric and a free spirit, a true nonconformist, but not an individualist.

Indeed, from his position high in the leaves, Cosimo is often the one to bring the community together. He is a born leader, and is able to organise the villagers into firefighting squads during a time of drought.

Because, for all its fantastical setting and implausible adventures, The Baron in the Trees is still a novel with a political edge, or what in Italian literature is called impegno (political commitment).

The baron’s life embodies the struggle of the intellectual to contribute meaningfully to society, albeit from a position of isolation and distance. This was a struggle Calvino himself had to contend with. He entered adulthood towards the end of World War II, having spent well over a year in the Resistance.

Earlier works

His early work was strongly marked by political themes, but by the 1950s he had begun to see the nexus between politics and literature somewhat differently.

Baron in the Trees, as well as the novels immediately preceding and following it (The Cloven Viscount and The Non-Existent Knight), with which it is now often published as a trilogy of sorts under the title, Our Ancestors) mark the beginning of a move from realism towards a more allegorical and, later, experimental kind of writing.

All three books are deeply philosophical, yet at the same time easy to read and entertaining.

Flickr, CC BY

Lightness was a key literary value for Calvino, specifically “the search for lightness as a reaction to the weight of living”, as he put it in Six Memos for the New Millennium.

Cosimo is the very embodiment of this search. Even the baron’s final moments are both poetic and principled as, despite old age and infirmity, he manages to find a way never to return to earth, not even in death.

The Baron in the Trees appeared in English translation (by Archibald Colquhoun) just two years after its original publication in Italy. Fifty years on, a new translation, by Ann Goldstein, has appeared, testament to the novel’s enduring popularity. For despite its historical-fantastical setting, there is a message for our times in this novel, which asks us to question our anthropocentric view of our environment.

The longer Cosimo spends in the trees, the greater his identification with the natural world. His eyes are said to have become like a cat’s or an owl’s, and he begins making speeches and distributing pamphlets advocating greater communion between humans and birds.

Some townspeople view this as a sign of madness but Cosimo is a deeply rational man who believes that “anyone who wishes to look closely at the earth must keep at a necessary distance”.

We, too, have something to learn from Cosimo and the natural world.![]()

Brigid Maher, Senior Lecturer in Italian Studies, La Trobe University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.