The link below is to an article that takes a look at 14 of the world’s best bookshops.

For more visit:

https://www.epicreads.com/blog/best-bookstores-world/

The link below is to an article that takes a look at 14 of the world’s best bookshops.

For more visit:

https://www.epicreads.com/blog/best-bookstores-world/

The link below is to an article with some tips on how to read slowly.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2019/10/07/how-to-read-slowly/

The link below is to another article reporting on the fallout from Peter Handke’s win of the Nobel Prize for Literature.

For more visit:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/oct/21/swedish-academy-defends-peter-handkes-controversial-nobel-win

The link below is to an article reporting on the shortlist for the 2019 German Book Prize.

For more visit:

https://publishingperspectives.com/2019/09/german-book-prize-releases-2019-shortlist-generational-shift/

Simon Ryan, Australian Catholic University

When in 2017 Nordstrom began selling US$425 jeans (A$620) covered in fake mud, it seemed the long prophesied “late stage capitalism” had finally arrived. Suddenly the phrase itself was everywhere from Reddit to Twitter and applied to every freakish story about excessive consumption or corporate perfidy.

Earlier this year, meanwhile, US President Donald Trump expressed an interest in buying Greenland, blithely ignoring national feeling in Denmark and the local attachment of the Inuit inhabitants. It seems to many we are living in a period in which national and cultural meanings are being drained by the inanities and indignities of an economic system that regards humans as units of production and consumption and nothing more.

Heather Rose’s Bruny takes up this sense that national boundaries and local attachments can be dissolved by the relentless power of capital. Bruny is a departure from Rose’s previous work, The Museum of Modern Love, for which she won the Stella Prize in 2017.

The compelling protagonist of Bruny is New York-based UN mediator Astrid (Ace) Coleman. She is cynical, efficient and covertly working for a state intelligence organisation.

A Tasmanian by birth, she escaped at the first opportunity from an island she found provincial and suffocating. But when one of the supports of the nearly completed bridge to Bruny island is blown up, she returns to manage the tensions between construction workers and anti-bridge protestors.

Read more:

Exquisite prose, with rare and subtle insight

Bruny is a family drama. Rather improbably, Astrid’s brother, known as JC, is the Premier of Tasmania, while her sister Max is leader of the opposition Labor party. Their mother is a difficult person facing serious illness and their father can only speak in Shakespearean phrases after a series of strokes. To his credit, the quotes are invariably relevant.

In the novel, the Tasmanian government has a network of commercial-in-confidence agreements that defy transparency. When part of a $2 billion bridge being built to connect mainland Tasmania with picturesque Bruny Island is destroyed, it is quickly agreed that hundreds of Chinese workers will be imported to complete it by the target date. But who has blown it up and why?

China is the source of capital for construction and has plans for Tasmania. Large scale population removal is one of the key features of European colonisation – see Palm Island. Australia’s repressed history returns uncannily in novels of invasion published as early as 1877, however, the xenophobia that energised these works is discharged carefully in Bruny through some sympathetic Chinese who have opted to settle in Tasmania and understand the attractions of its isolation and space.

Bruny’s central premise (which continues this literary invasion theme) contains a revelation that once would have been clearly absurd, threatening the realism a political thriller requires.

Readers might choose to consider this dramatic revelation as satirical. The novel mixes family drama, political intrigue and geopolitical speculation in ways that seem exaggerated and improbable. Yet elements are not so far removed from possibility, leaving a feeling of unease reminiscent of Sinclair Lewis’ 1935 novel about American fascism, It Can’t Happen Here.

There are a few flaws in the novel. As potential satire, it does not have to draw complex secondary characters, but insofar as it is a family drama the failure to do so weakens the effect. Perhaps this is an unavoidable outcome of the hybrid genre, but one might feel the politically powerful siblings, JC and Max, are not developed beyond caricature.

And there are a few elements in the writing that grate. Characters are repeatedly described by their likeness to actors – including Christopher Pike, Gene Hackman, and Chris Hemsworth.

Elsewhere Monty Python is misquoted. The epithet shouted at the Popular Front of Judea in Life of Brian is “splitter” not “quitter”. It is a minor point but distracting.

Structurally, the pacing is quite slow until the pivotal revelation and then things move quickly – perhaps too quickly. The treacherous or weak federal politicians fade from the scene and Tasmanian quislings are punished by losing office – a benign punishment given the scale of their betrayal. However, there are balancing pleasures, such as seeing the quick and intuitive intelligence of Ace at work and the loving descriptions of the landscape.

It is not giving away too much to say the heroes in the novel are the intelligence agencies, functioning as the last defence of liberal democracy. One only has to read opinion sites to realise the final, desperate hope of some in the centre-left of politics is that certain agencies may intervene to maintain the stability of the geopolitical order.

Bruny captures this sense of everything being up for sale. The novel portrays a political class working at the behest of capital and ambition. The novel catalogues contemporary concerns: the power of China, the ability of capital to erode beliefs and cultures, the repression of protest and the complicity of local politicians with international interests.![]()

Simon Ryan, Associate Professor (Literature), Australian Catholic University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

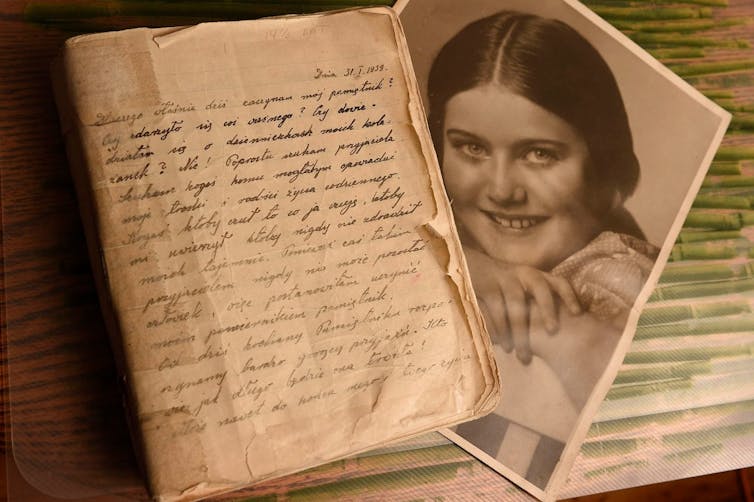

The first entry in Renia Spiegel’s diary is dated January 31, 1939: “Today, my dear Diary, is the beginning of our deep friendship. Who knows how long it will last?” The 14-year-old girl, living with her grandparents in Przemyśl (halfway between Cracow and Lwów, Poland), was not to know that on the previous day, Hitler was delivering probably the most famous speech of his career in the specially recalled Reichstag. This fateful speech included his “prophecy” in which he declared that:

If international finance Jewry in and outside Europe succeeds in plunging nations into another world war, then the end result will not be the Bolshevisation of the planet and thus the victory of the Jews – it will be the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe.

The contrast reveals the madness of the Holocaust: a Nazi leadership obsessed with the supposed threat posed by the “international Jew” and an ordinary Jewish adolescent voicing her hopes, dreams, concerns and fears in the manner of millions of other teenagers.

Yet Renia Spiegel was in one respect not an ordinary teenager. Her life was blighted by the time and place in which she grew up, with the result that her aspirations were cruelly thwarted.

The survival of her diary, which was kept first by her boyfriend and then by her sister for many decades, is remarkable. Its contents are a fascinating read – if somewhat uncomfortable, for one is permanently peering into the innermost thoughts of a young girl on the verge of adulthood – and show that Renia was a highly intelligent young woman and a talented writer.

Her poetry, which takes up many pages of the diary, is remarkably confident and poised for an aspiring teenage poet. While not all of it would be considered of publishable quality were it not for the context in which it was written, it displays many of the techniques that Renia would undoubtedly have honed later, had she survived.

The diary has been hailed as a lost masterpiece of Holocaust-era writing. The blurb on the jacket, for example, from the Smithsonian Magazine, describes it as “astonishing … a new invaluable contribution to Holocaust literature”. This is somewhat misleading.

The context in which Renia wrote the diary was indeed that of, first, the Soviet occupation of eastern Poland in September 1939, and then, after June 1941, the German occupation, with all that entailed: round-ups, shootings, the yellow star, the creation of the ghetto, the scramble to obtain work permits to avoid deportation.

Yet in the nearly 400 pages that make up the diary, this context is barely mentioned. This is quite clearly not because Renia was so immersed in her studies and falling in love that she neither noticed nor cared about what was going on around her. She cared deeply, as the few entries dealing directly with the war and what it meant for the Jews of Poland attest. But she made the choice to write in her diary primarily about her day-to-day life.

Perhaps she saw the diary as a means of escape from persecution, but it is in any case mostly filled with ordinary teenage preoccupations: schooling, parties, fallings-out and making friends again. There’s also a long-running “He loves me, he loves me not” saga with the boy who would become her boyfriend and, eventually, the saviour of the diary – Zygmunt Schwarzer. How the diary found its way from wartime Poland to New York and to a publisher is another long story recounted here.

That said, there are moments when the reality of the world around punctures what is mostly a reflection on Renia’s inner life. These tend to occur at crucial, life-changing moments. On July 1, 1941, for example, she writes:

Today I’m like everyone else … Tomorrow, along with other Jews, I’ll have to start wearing a white armband. To you I will always remain the same Renia, a friend, but to others I will become someone inferior, I will become someone wearing a white armband with a blue star. I will be a Jude.

And on July 5, 1942, she adds an entry which indicates the extent to which her life was shaped by events about which she chose for the most part not to write about: “We feared it, it threatened us and then it finally happened. What we were so afraid of has finally come after all. The ghetto.”

But these moments of explicit reference to the war and the persecution of the Jews are few and far between.

If this is not quite the text it appears, that is not Renia’s fault, but a question of marketing. Deborah Lipstadt rightly notes in her introduction that but for the diary “she would have gone, together with millions of others, into the cruel oblivion that was the fate of most Holocaust victims”.

That is the justification for publishing this deeply personal text. But Renia obviously did not regard her diary as a contribution to “Holocaust literature” – it is, rather, a record of the interior monologue of a gifted and thoughtful young woman, who had the misfortune to grow up in that time and place.

The diary should be read for what it is – which will mean readers having to disregard to quite a large extent the way the book has been dressed up.![]()

Dan Stone, Professor of Modern History, Royal Holloway

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Clare Hutton, Loughborough University

For the first time since 1992 – and only the third time in the illustrious history of the Booker – the prize has been awarded to two novels: The Testaments by Margaret Atwood, and Girl, Woman, Other by Bernardine Evaristo.

In accepting the shared prize, both women were gracious. Atwood, at 79, felt that she was “too elderly”, and was happy to share; and Evaristo was honoured to share with the feminist literary legend. The £50,000 prize is to be divided and Atwood has announced that her £25,000 will be donated to the charity Indspire, which aims to enrich Canada through Indigenous education.

The value of winning the Booker is not just the honour, of course. For most authors, the value is the cash prize and the huge increase in sales which follows from the win. Last year’s winning title, Milkman by Anna Burns, has sold more than 500,000 copies and has changed Burns’s life immeasurably, as she made clear in a moving speech at last night’s black-tie awards dinner in London’s Guildhall.

As the sequel to The Handmaid’s Tale (1985), The Testaments is already a conspicuous and assured commercial success. Live launched in 130 cinemas worldwide on September 10, the hardback edition has sold more than 179,000 copies in the UK and has performed well in terms of downloads as well. Meanwhile, the other winning title – Girl, Woman, Other – has sold only 4,000 copies in the UK to date, according to Nielsen Bookscan.

The Booker Prize process takes novels of a very different kind and places them on the same list. A panel of five judges is appointed each year and they spend most of that year reading submissions. This year, the panel, chaired by Peter Florence, got through 180 novels in 11 months. Having produced a longlist of 13 novels in July and a shortlist of six in early September, the jury’s task was to choose one winner in accordance with the published rules which explicitly state that: “The Prize may not be divided or withheld.”

This rule was established in 1992, because a committee chaired by Victoria Glendinning insisted on two winners: Sacred Hunger by Barry Unsworth and The English Patient by Michael Ondaatje. Even a year later, this palled with the well-known literary agent Giles Gordon, who thought that the Booker is about “winning not sharing”.

That a panel of five could not reach a consensus after hours of discussion elicited gasps of frustration and indignation from those who were at the Guildhall. It suggests that at least one panel member was exercising some sort of veto, and brings to mind the story of Philip Larkin, chair of the judges in 1977, who threatened to jump out the window if the title he preferred did not win (it did).

But Florence preferred consensus to coercion – and the panel wanted to signal that both winners are of particular note. That’s the official line, anyway.

The Testaments and Girl, Woman, Other are very different kinds of books, by very different kinds of author and will appeal to different kinds of readers. For Florence, it may be a case of “double the joy” and “double the reading pleasure”, but others will wish to choose.

The Testaments is assured, compelling, carefully plotted, slickly written and worthy of the hype. The structure of three different types of “testimony” – that of Aunt Lydia and two Gilead witnesses – is especially appealing and works well. It is a book which reads quickly and its appearance now, so many years after The Handmaid’s Tale, is testament to Atwood’s vision – and creative resilience.

Resilience has clearly been a huge issue for Evaristo, who is a longstanding advocate for the inclusion of people of colour in the arts. Born in London in 1959 to a white English mother and Nigerian father, Evaristo was educated at Rose Bruford Drama School and Goldsmith’s College. She founded the Theatre of Black Women in 1982, and has written seven novels to date.

Girl, Woman, Other is a multi-stranded narrative which gives voice to the experience of being a black British woman through 12 interwoven stories ranging from Newcastle in 1905, through London 1980, Oxford in 2008 and Northumberland in 2017. The work abandons the conventions of standard paragraphing and punctuation, a technique which has lead some readers to describe the form as “free verse”.

But Evaristo’s prose lacks the compression, lyricism and intensity of verse and this book often plays to very predictable cliché. This, arguably, is the point: cliché enables us to see beyond – and to think through – the issues of diversity and representation which are so central to individual racial experience.

Speaking last night, Atwood herself said: “I kind of don’t need the attention.” When she won the Booker in 2000 with The Blind Assassin, she had already been nominated on three other occasions, including in 1986 when The Handmaid’s Tale lost out to The Old Devils by Kingsley Amis.

Perhaps the judges should have weighed these losses and gains in the balance. If Evaristo’s work is worth honouring then surely it was worth the honour which would have come from being the sole recipient of the Booker Prize 2019.![]()

Clare Hutton, Senior Lecturer in English, Loughborough University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Why do we tell stories, and how are they crafted? In this series, we unpick the work of the writer on both page and screen.

Anna Spargo-Ryan’s debut novel, The Paper House (2016), is a layered articulation of loss and grief, perception and reality. It explores the nature of reality as felt and lived by protagonist Heather – not always what the other characters consider as real.

The Paper House takes the reader into Heather’s means of escape: the almost mythical garden of her new house where she meets people, both real and unreal. The characters Heather meets help her to come to terms with grief, and allow her to repair fractured relationships. The journey takes Heather through hidden places in her new garden and through her memories of her childhood and her mother.

Spargo-Ryan employs figurative language and imagery as a structural device, enabling thematic concerns to become part of the way the novel is built. The nature of reality is considered not only through the narrative, but also through use of startling metaphors and exactingly vivid imagery.

Most authors make use of metaphor when they write: something described as something else in order to draw a non-literal connection. To give an example from The Paper House: “The world and I collided, saucepans on a rack”. This expression allows the reader to imagine the violence, noise and antagonism.

Metaphors work to challenge or surprise readers to see the characters and topics under investigation in a new way.

In Spargo-Ryan’s novel, metaphors are used in conjunction with imagery, creating a unique picture in the mind of the reader.

I could hear the panic churning in his bone marrow and I wanted to run from the radiology department but equally I didn’t want to rupture and die in the hallway

Metaphor and imagery can be used to develop settings, characters and themes. The use of figurative language to develop themes demands a consistent thread – a structural use of metaphor and imagery.

In The Paper House, metaphors dovetail into concepts surrounding the nature of reality and the literal in opposition to the fabricated, misremembered or delusional.

I found myself collecting metaphors from within the book, plucking them like the flowers Heather draws in her sketchbook, pressing them between the pages of my journal for the simple joy of collecting something beautiful.

Spargo-Ryan’s use of metaphor expands beyond examples of comparison creating pictures (the streets “hiccupped with children”). Instead, these images dictate the reader’s whole experience of reality: a building block of the narrative challenging assumptions we make about what we are shown by the protagonist.

Slowly and gently, the reader becomes aware much of the reality we have been experiencing with Heather is not objectively real. It is merely her sense of reality. Heather’s book of drawings – currawong, lemon-scented tea tree, ironbark – turns out to be “page after page of a little girl’s face”.

Read more:

Stories for hyperlinked times: the short story cycle and Rebekah Clarkson’s Barking Dogs

Aristotle argued mastery of metaphor was a sign of genius. A well-formed metaphor can conjure a new way of seeing. Perhaps the idea of being a genius with metaphors also lies in the fact using figurative language can present writers with a number of pitfalls.

There is an art to writing metaphors and to their effective use. Spargo-Ryan uses the following sentence to pull together Heather’s memories of her father as a man broken by her mother’s mental illness:

He had looked at me with his heart in his eyes and his eyes in a hole, and his shoulders sagged at the corners, and his body was just a skeleton on a coat hanger.

The reader is left with a startling picture of a man worn down and eaten up by his love.

The difficulties writers sometimes have with metaphor can come down to a question of balance. The trap for authors lies in the trickiness in over- or under-extending the metaphor. If a metaphor is not taken far enough or is too close to the literal meaning, it might not be recognised as metaphor and feel inaccurate or jarring. Similarly, well-established metaphors (a “rollercoaster of emotions”) make writing clichéd.

Spargo-Ryan goes beyond Aristotle’s notion of genius.

At the very beginning of the novel, Heather and her husband suffer a shattering loss: “for five days we sent our bodies into the world without us”.

During this time, Heather describes herself as “a girl who had become a stocking” – and this insubstantiality is reflected in later descriptions of students. Young people are described as gathering “around tables and bus stops and any other anchor they could find”, as if their bodies alone are not enough to hold them to the ground.

Metaphors in this novel continually engage in a productive interplay developing thematic and structural considerations. The beauty of Spargo-Ryan’s writing ensures her metaphors work on a micro level but also on a macro level, developing content and theme.

One image reminds the reader of a previous one. The whole becomes greater than the sum of its parts. Spargo-Ryan’s metaphors act as a way of both supporting and structuring the narrative. Aristotle would approve.![]()

Debra Wain, Academic in Professional and Creaive Writing, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The links below are to articles reporting on the shortlist for the 2019 Goldsmiths Prize.

For more visit:

– https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2019/10/03/140275/goldsmiths-prize-2019-shortlist-announced/

– https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/oct/02/goldsmiths-prize-shortlist-fiction

You must be logged in to post a comment.