CHRISTO DRUMMKOPF/flickr, CC BY

Susanna Lee, Georgetown University

At the end of May, it happened again. A mass shooter killed 12 people, this time at a municipal center in Virginia Beach. Employees had been forbidden to carry guns at work, and some lamented that this policy had prevented “good guys” from taking out the shooter.

This trope – “the good guy with a gun” – has become commonplace among gun rights activists.

Where did it come from?

On Dec. 21, 2012 – one week after Adam Lanza shot and killed 26 people at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut – National Rifle Association Executive Vice President Wayne LaPierre announced during a press conference that “the only way to stop a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun.”

Ever since then, in response to each mass shooting, pro-gun pundits, politicians and social media users parrot some version of the slogan, followed by calls to arm the teachers, arm the churchgoers or arm the office workers. And whenever an armed citizen takes out a criminal, conservative media outlets pounce on the story.

But “the good guy with the gun” archetype dates to long before LaPierre’s 2012 press conference.

There’s a reason his words resonated so deeply. He had tapped into a uniquely American archetype, one whose origins I trace back to American pulp crime fiction in my book “Hard-Boiled Crime Fiction and the Decline of Moral Authority.”

Other cultures have their detective fiction. But it was specifically in America that the “good guy with a gun” became a heroic figure and a cultural fantasy.

‘When I fire, there ain’t no guessing’

Beginning in the 1920s, a certain type of protagonist started appearing in American crime fiction. He often wore a trench coat and smoked cigarettes. He didn’t talk much. He was honorable, individualistic – and armed.

These characters were dubbed “hard-boiled,” a term that originated in the late 19th century to describe “hard, shrewd, keen men who neither asked nor expected sympathy nor gave any, who could not be imposed upon.” The word didn’t describe someone who was simply tough; it communicated a persona, an attitude, an entire way of being.

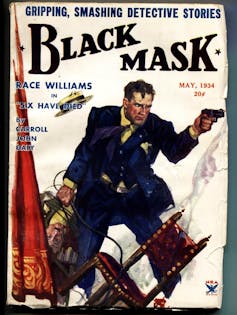

Most scholars credit Carroll John Daly with writing the first hard-boiled detective story. Titled “Three Gun Terry,” it was published in Black Mask magazine in May 1923.

Abe Books

“Show me the man,” the protagonist, Terry Mack, announces, “and if he’s drawing on me and is a man what really needs a good killing, why, I’m the boy to do it.”

Terry also lets the reader know that he’s a sure shot: “When I fire, there ain’t no guessing contest as to where the bullet is going.”

From the start, the gun was a crucial accessory. Since the detective only shot at bad guys and because he never missed, there was nothing to fear.

Part of the popularity of this character type had to do with the times. In an era of Prohibition, organized crime, government corruption and rising populism, the public was drawn to the idea of a well-armed, well-meaning maverick – someone who could heroically come to the defense of regular people. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, stories that featured these characters became wildly popular.

Taking the baton from Daly, authors like Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler became titans of the genre.

Their stories’ plots differed, but their protagonists were mostly the same: tough-talking, straight-shooting private detectives.

In an early Hammett story, the detective shoots a gun out of a man’s hand and then quips he’s a “fair shot – no more, no less.”

In a 1945 article, Raymond Chandler attempted to define this type of protagonist:

“Down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid. … He must be, to use a rather weathered phrase, a man of honor, by instinct, by inevitability, without thought of it, and certainly without saying it.”

As movies became more popular, the archetype bled into the silver screen. Humphrey Bogart played Dashiell Hammett’s Sam Spade and Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe to great acclaim.

By the end of the 20th century, the fearless, gun-toting good guy had become a cultural hero. He had appeared on magazine covers, movie posters, in television credits and in video games.

Selling a fantasy

Gun rights enthusiasts have embraced the idea of the “good guy” as a model to emulate – a character role that just needed real people to step in and play it. The NRA store even sells T-shirts with LaPierre’s slogan, and encourages buyers to “show everyone that you’re the ‘good guy’” by buying the T-shirt.

NRA Store

The problem with this archetype is that it’s just that: an archetype. A fictional fantasy.

In pulp fiction, the detectives never miss. Their timing is precise and their motives are irreproachable. They never accidentally shoot themselves or an innocent bystander. Rarely are they mentally unstable or blinded by rage. When they clash with the police, it’s often because they’re doing the police’s job better than the police can.

Another aspect of the fantasy involves looking the part. The “good guy with a gun” isn’t just any guy – it’s a white one.

In “Three Gun Terry,” the detective apprehends the villain, Manual Sparo, with some tough words: “‘Speak English,’ I says. I’m none too gentle because it won’t do him any good now.”

In Daly’s “Snarl of the Beast,” the protagonist, Race Williams, takes on a grunting, monstrous immigrant villain.

Could this explain why, in 2018, when a black man with a gun tried to stop a shooting in a mall in Alabama – and the police shot and killed him – the NRA, usually eager to champion good guys with guns, didn’t comment?

A reality check

Most gun enthusiasts don’t measure up to the fictional ideal of the steady, righteous and sure shot.

In fact, research has shown that gun-toting independence unleashes much more chaos and carnage than heroism. A 2017 National Bureau of Economic Research study revealed that right-to-carry laws increase, rather than decrease, violent crime. Higher rates of gun ownership is correlated with higher homicide rates. Gun possession is correlated with increased road rage.

There have been times when a civilian with a gun successfully intervened in a shooting, but these instances are rare. Those who carry guns often have their own guns used against them. And a civilian with a gun is more likely to be killed than to kill an attacker.

Even in instances where a person is paid to stand guard with a gun, there’s no guarantee that he’ll fulfill this duty.

Hard-boiled novels have sold in the hundreds of millions. The movies and television shows they inspired have reached millions more.

What started as entertainment has turned into a durable American fantasy.

Maintaining it has become a deadly American obsession.

[ Like what you’ve read? Want more? Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter. ]![]()

Susanna Lee, Professor of French and Comparative Literature, Georgetown University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.