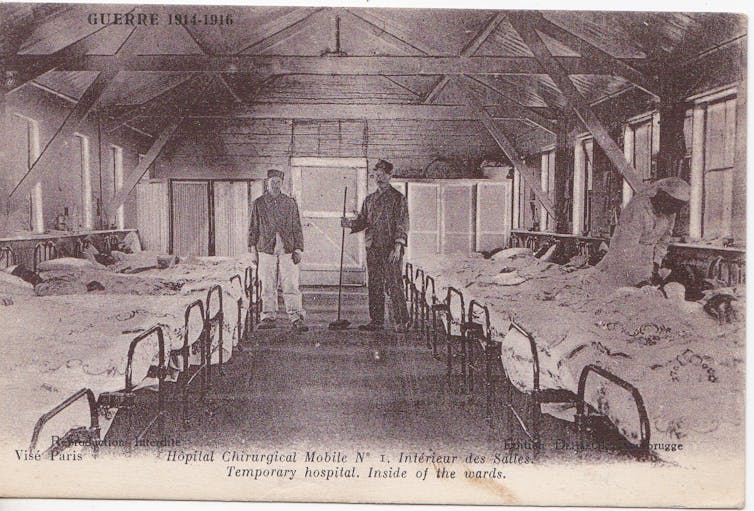

Courtesy of the National Archives, College Park, Maryland, Author provided

Cynthia Wachtell, Yeshiva University

Virtually everyone has heard of Ernest Hemingway. But you’d be hard-pressed to find someone who knows of Ellen N. La Motte.

People should.

She is the extraordinary World War I nurse who wrote like Hemingway before Hemingway. She was arguably the originator of his famous style – the first to write about World War I using spare, understated, declarative prose.

Long before Hemingway published “A Farewell to Arms” in 1929 – long before he even graduated high school and left home to volunteer as an ambulance driver in Italy – La Motte wrote a collection of interrelated stories titled “The Backwash of War.”

Published in the fall of 1916, as the war advanced into its third year, the book is based upon La Motte’s experience working at a French field hospital on the Western Front.

“There are many people to write you of the noble side, the heroic side, the exalted side of war,” she wrote. “I must write you of what I have seen, the other side, the backwash.”

“The Backwash of War” was immediately banned in England and France for its criticism of the ongoing war. Two years and multiple printings later – after being hailed as “immortal” and America’s greatest work of war writing – it was deemed damaging to morale and also censored in wartime America.

For nearly a century, it languished in obscurity. But now, an expanded version of this lost classic that I’ve edited has just been published. Featuring the first biography of La Motte, it will hopefully give La Motte the attention she deserves.

Horrors, not heroes

In its time, “The Backwash of War” was, simply put, incendiary.

As one admiring reader explained in July 1918, “There is a corner of my book-shelves which I call my ‘T N T’ library. Here are all the literary high explosives I can lay my hands on. So far there are only five of them.” “The Backwash of War” was the only one by a woman and also the only one by an American.

In most of the era’s wartime works, men willingly fought and died for their cause. The characters were brave, the combat romanticized.

Not so in La Motte’s stories. Rather than focus on World War I’s heroes, she emphasized its horrors. And the wounded soldiers and civilians she presents in “The Backwash of War” are fearful of death and fretful in life.

Filling the beds of the field hospital, they are at once grotesque and pathetic. There is a soldier slowly dying from gas gangrene. Another suffers from syphilis, while one patient sobs and sobs because he does not want to die. A 10-year-old Belgian boy is fatally shot through the abdomen by a fragment of German artillery shell and bawls for his mother.

War, to La Motte, is repugnant, repulsive and nonsensical.

The volume’s first story immediately sets the tone: “When he could stand it no longer,” it begins, “he fired a revolver up through the roof of his mouth, but he made a mess of it.” The soldier is transported, “cursing and screaming,” to the field hospital. There, through surgery, his life is saved but only so that he can later be court-martialed for his suicide attempt and killed by a firing squad.

Cynthia Wachtell

After “The Backwash of War” was published, readers quickly recognized that La Motte had invented a bold new way of writing about war and its horrors. The New York Times reported that her stories were “told in sharp, quick sentences” that bore no resemblance to conventional “literary style” and delivered a “stern, strong preachment against war.”

The Detroit Journal noted she was the first to draw “the real portrait of the ravaging beast.” And the Los Angeles Times gushed, “Nothing like [it] has been written: it is the first realistic glimpse behind the battle lines… Miss La Motte has described war – not merely war in France – but war itself.”

La Motte and Gertrude Stein

Together with the famous avant-garde writer Gertrude Stein, La Motte seems to have influenced what we now think of as Hemingway’s signature style – his spare, “masculine” prose.

Library of Congress

La Motte and Stein – both middle-aged American women, writers and lesbians – were already friends at the start of the war. Their friendship deepened during the first winter of the conflict, when they were both living in Paris.

Despite the fact that they each had a romantic partner, Stein seems to have fallen for La Motte. She even wrote a “little novelette” in early 1915 about La Motte, titled “How Could They Marry Her?” It repeatedly mentions La Motte’s plan to be a war nurse, possibly in Serbia, and includes revealing lines such as “Seeing her makes passion plain.”

Without a doubt Stein read her beloved friend’s book; in fact, her personal copy of “The Backwash of War” is presently archived at Yale University.

Hemingway writes war

Ernest Hemingway wouldn’t meet Stein until after the war. But he, like La Motte, found a way to make it to the front lines.

In 1918, Hemingway volunteered as an ambulance driver and shortly before his 19th birthday was seriously injured by a mortar explosion. He spent five days in a field hospital and then many months in a Red Cross hospital, where he fell in love with an American nurse.

After the war, Hemingway worked as a journalist in Canada and America. Then, determined to become a serious writer, he moved to Paris in late 1921.

In the early 1920s Gertrude Stein’s literary salon attracted many of the emerging postwar writers, whom she famously labeled the “Lost Generation.”

Among those who most eagerly sought Stein’s advice was Hemingway, whose style she significantly influenced.

“Gertrude Stein was always right,” Hemingway once told a friend. She served as his mentor and became godmother to his son.

Much of Hemingway’s early writing focused on the recent war.

“Cut out words. Cut everything out,” Stein counseled him, “except what you saw, what happened.”

Very likely, Stein showed Hemingway her copy of “The Backwash of War” as an example of admirable war writing. At the very least, she passed along what she had learned from reading La Motte’s work.

Whatever the case, the similarity between La Motte’s and Hemingway’s styles is plainly evident. Consider the following passage from the story “Alone,” in which La Motte strings together declarative sentences, neutral in tone, and lets the underlying horror speak for itself.

“They could not operate on Rochard and amputate his leg, as they wanted to do. The infection was so high, into the hip, it could not be done. Moreover, Rochard had a fractured skull as well. Another piece of shell had pierced his ear, and broken into his brain, and lodged there. Either wound would have been fatal, but it was the gas gangrene in his torn-out thigh that would kill him first. The wound stank. It was foul.”

Now consider these opening lines from a chapter of Hemingway’s 1925 collection “In Our Time”:

“Nick sat against the wall of the church where they had dragged him to be clear of machine-gun fire in the street. Both legs stuck out awkwardly. He had been hit in the spine. His face was sweaty and dirty. The sun shone on his face. The day was very hot. Rinaldi, big backed, his equipment sprawling, lay face downward against the wall. Nick looked straight ahead brilliantly…. Two Austrian dead lay in the rubble in the shade of the house. Up the street were other dead.”

Hemingway’s declarative sentences and emotionally uninflected style strikingly resemble La Motte’s.

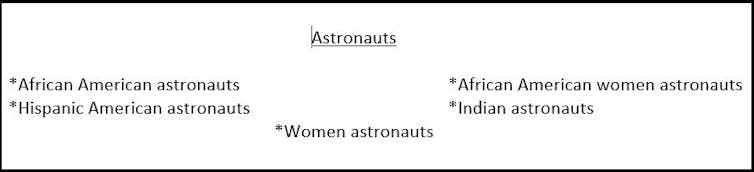

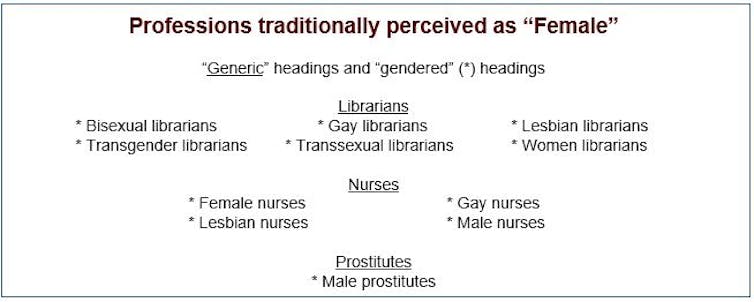

So why did Hemingway receive all of the accolades, culminating in a Nobel Prize in 1954 for the “influence he exerted on contemporary style,” while La Motte was lost to literary oblivion?

Was it the lasting impact of wartime censorship? Was it the prevalent sexism of the postwar era, which viewed war writing as the purview of men?

Whether due to censorship, sexism or a toxic combination of the two, La Motte was silenced and forgotten. It’s time to return “The Backwash of War” to its proper perch as a seminal example of war writing.

The Backwash of War: An Extraordinary American Nurse in World War I![]()

Cynthia Wachtell, Research Associate Professor of American Studies & Director of the S. Daniel Abrham Honors Program, Yeshiva University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.