The link below is to an article that considers the role of the book review in the current digital age.

For more visit:

https://harpers.org/archive/2019/04/like-this-or-die/

The link below is to an article that considers the role of the book review in the current digital age.

For more visit:

https://harpers.org/archive/2019/04/like-this-or-die/

Katharine Capshaw, University of Connecticut and Cora Lynn Deibler, University of Connecticut

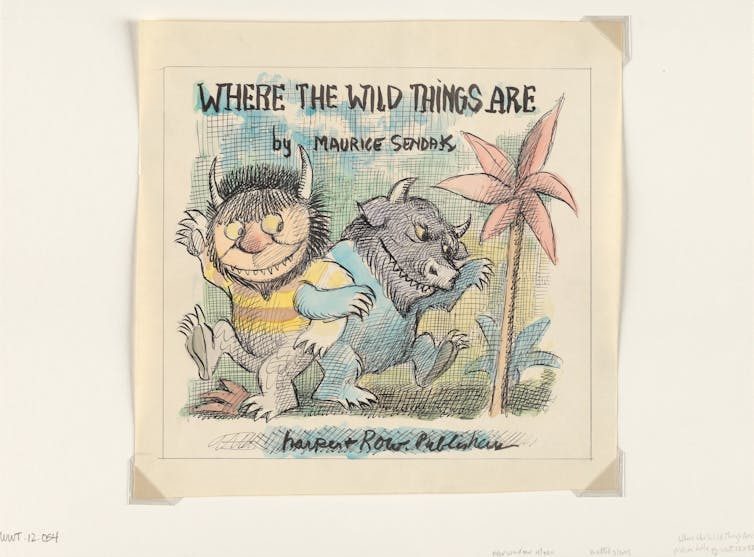

Fans of “Where the Wild Things Are,” Maurice Sendak’s most famous book, might know every page by heart.

But few know the winding path it took from idea to published book – a gestation process that involved experimentation, playfulness and persistence.

As professors of children’s literature and illustration, we are thrilled to witness the arrival of The Maurice Sendak Collection at the University of Connecticut’s Archives and Special Collections at the Thomas J. Dodd Center. The collection – which contains Sendak’s original sketches, book dummies, artwork and final drafts of his work, amounting to nearly 10,000 items – allows us to begin to trace the trajectory of Sendak’s creative process.

It contains evidence of Sendak’s prodigious imagination and lifelong intellectual curiosity, and offers insight into how Sendak developed his ideas over time.

The making of “Where the Wild Things Are” was a journey, and the vivid materials in Sendak’s archive illuminate the level of investment that was required to complete it.

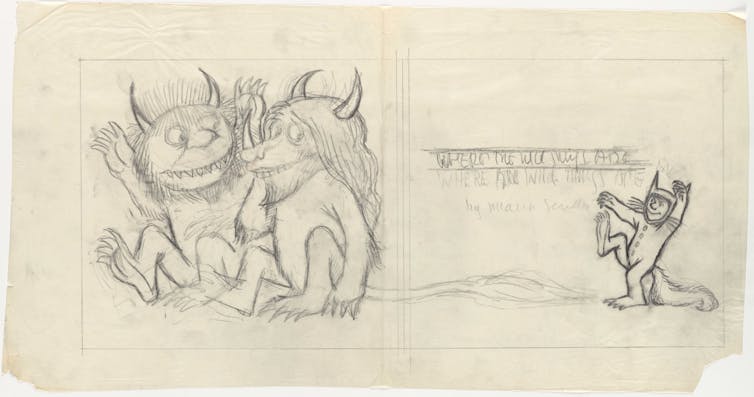

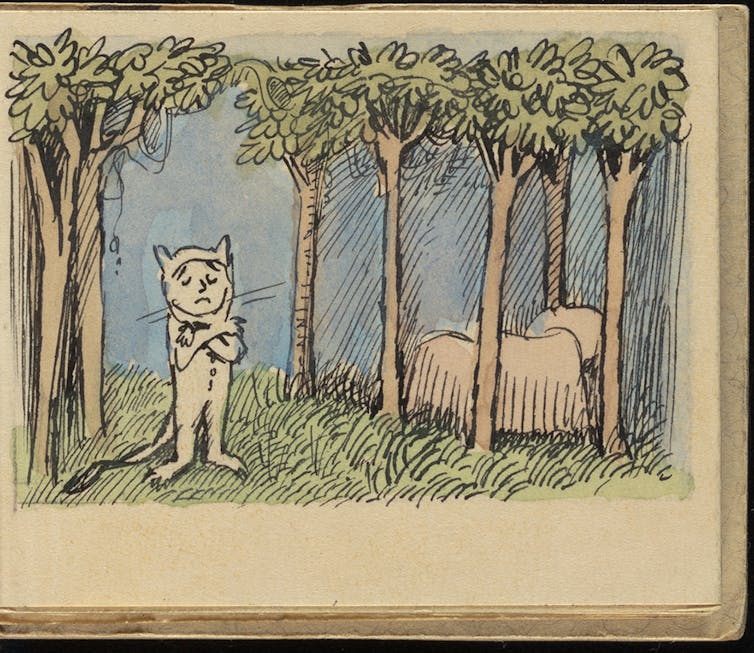

One of the items in the collection is a small, horizontal book dummy dated Nov. 17, 1955, titled “Where the Wild Horses Are.” As one of the earliest forms of what would become “Where the Wild Things Are,” the book dummy contains many of the elements that would appear in the final version, including a boy who takes a journey, gets chased by monsters and sails a boat to an island.

But what’s with the horses?

This earliest version includes images of the child pulling the animals’ tails. In response, they kick him into the air – and out of his clothes.

In interviews, Sendak claimed that, when revising the story, he gave up on horses because he couldn’t draw them. But Sendak spent his life immersing himself in a variety of art styles, from romantic painters William Blake and Domenico Tiepolo to American cartoonist Winsor McCay. Sendak possessed immense skill.

So if he wanted to illustrate horses, he probably would have. In fact, in 1955 he handily illustrated “Charlotte and The White Horse,” a children’s book authored by Ruth Krauss, with whom he had a longstanding collaborative relationship.

But Sendak must have decided horses weren’t right for this story, and he took time to let his ideas percolate.

The wild things do appear in his other surviving book dummy, which is entirely recognizable as an early stage of the finished book we now know. Appearing eight years after the first dummy, this one, square and slightly larger than the first, shows the evolution of the book’s characters and visual rhythm. The changing borders – think of the page in which the trees take over Max’s bedroom – compel the reader to turn the pages.

“I had never seen fantasy depicted in American children’s books in illustrations that were so powerfully in motion,” critic Nat Hentoff wrote in the New Yorker in 1966, a few years after the book’s publication.

But what happened during the preceding eight years?

Much of the time was spent focusing on other projects. Sendak illustrated other picture books for his publisher, Harper and Row, and collaborated with Else Holmelund Minarik on her “Little Bear” series and with Ruth Krauss on books like “I Want to Paint my Bathroom Blue.”

He also published his own picture books during this period, from “Kenny’s Window” in 1956 to “The Sign on Rosie’s Door” in 1960.

Yet most picture book authors and illustrators work diligently and juggle multiple projects. How was Sendak different?

Unlike illustrators who use a singular style that appears throughout their work, Sendak developed a unique visual approach for each project. He was always seeking out inspiration from other artists whom he admired.

“Wild Things,” for example, owes a great deal to the influence of French post-impressionist painter Henri Rousseau. You can see the influence of Swiss painter Henry Fuseli on “Outside Over There” and the influences of British caricaturist Thomas Rowlandson and Czech painter Josef Lada on the recently published “Presto and Zesto in Limboland,” which Sendak created with friend and collaborator Arthur Yorinks.

He also read widely – he especially loved Herman Melville, Emily Dickinson and John Keats – and as he worked he played music in the background, choosing songs and albums that reflected his creative moods.

“Sketching to music is a marvelous stimulant to my imagination,” he said during his Caldecott award speech in 1964.

And he was always trying to become a better artist; he was, as Yorinks explained in an interview, “constantly teaching himself.” In the long gestation period between the dummy and the publication of “Where the Wild Things Are,” Sendak was able to learn a range of new styles, including the crosshatching technique that would appear in “Wild Things.”

As Jonathan Weinberg, curator and director of research at The Maurice Sendak Foundation, told us, “I can think of no other artist – illustrator or otherwise – who has employed so many different forms of expression, not only over time but often on projects that were in production simultaneously.”

During the period in which “Wild Horses” became “Wild Things,” Sendak enlarged the interpretive possibilities of his subject.

Just as Sendak fertilized his imagination with a range of artists and sensory experiences, from Mozart to Melville, the wild things themselves are hybrid creatures that possess qualities that are both human-like and animal-like. They roar but speak English, walk upright but have horns sprouting from their heads.

By drawing and redrawing the creatures, Sendak could play with their expressions and postures, toying with the ways they might move and engage the reader.

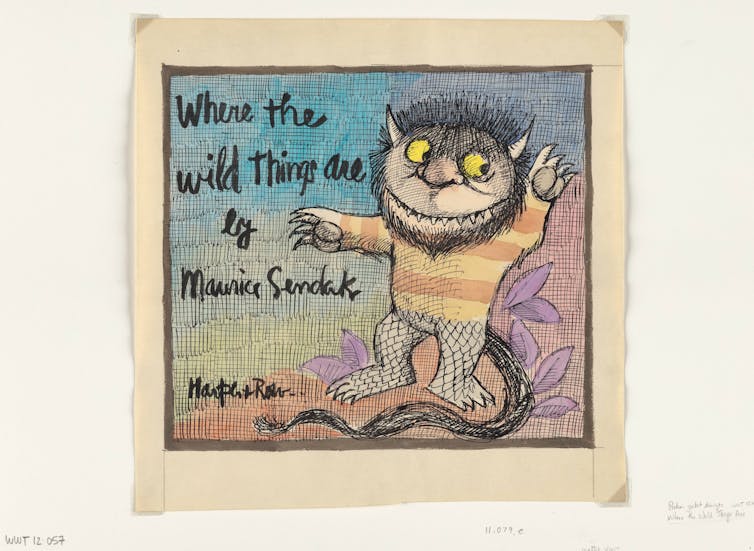

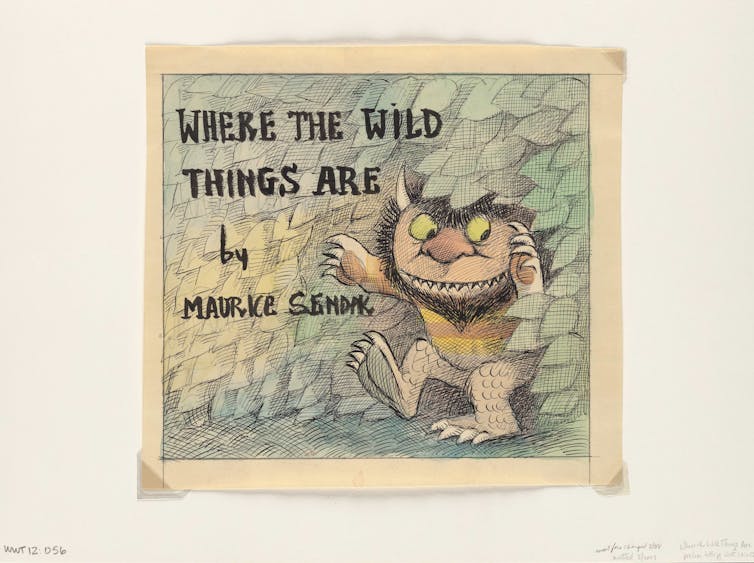

The Sendak Collection contains multiple versions of what would become the book’s jacket. Many of them focused on a particular wild thing wearing a striped sweater. In one version, he looks to the side as he waves to the reader.

In another, he creeps out from the underbrush, hands and foot raised in motion.

In a third, he seems to dance, arms locked with another creature, a smile on his face.

Even though these drafts don’t appear in the final version, they offer a window into Sendak’s imagination. Yes, attempting multiple drafts is a form of diligence. But it’s also creative play – a fusion of discipline with dynamism.

According to Lynn Caponera, president of The Maurice Sendak Foundation, the artist couldn’t have known that this book would eventually become his most significant work. But she can see why kids are so drawn to the book’s characters. The wild things, she noted – with their large heads, stumbling gait and round bodies – “have the proportions of toddlers, of King Kong, of Mickey Mouse.”

Perhaps that is why the wild things seem so fully to capture the humanity of the young – their longings and rage, their imagination and joy.

Picture books, Yorinks explained, are a medium that the “world doesn’t take seriously.” Yet Sendak decided to make them because they’re “the simplest form to express the most complicated thoughts and feelings.”

The materials at the University of Connecticut show how the work of writing and illustrating a book is a kind of journey, not unlike Max’s, into the deepest recesses of the imagination.![]()

Katharine Capshaw, Professor of English, University of Connecticut and Cora Lynn Deibler, Professor of Illustration, University of Connecticut

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that looks at whether paperbacks need to be upgraded as they age.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2019/02/15/do-beloved-paperbacks-need-an-upgrade/

The link below is to an article that shares some thoughts on writing from past Story Prize winners.

For more visit:

https://lithub.com/saunders-mccracken-and-more-advice-from-masters-of-the-short-story/

The link below is to an article that looks at the 2019 winner of the E. B. White Award for Literature, Katherine Paterson.

Sally O’Reilly, The Open University

The way women are portrayed is changing. In film, The Favourite has won numerous awards and features three women, variously wild and untameable, as joint protagonists. Other movies such as The Wife and Can You Ever Forgive Me? show older or unlovely women as sympathetic leads. Brava! But what’s happening in fiction? What are readers looking for in their modern, made-up women?

In this period of widening gender equality, it seems the time is right for new portrayals of women in fiction. Readers are diverse, and want many different things, and various female “archetypes” have existed since storytelling began. Early tales included murderesses and proxy witches such as the Greek figure Medea and Grendel’s mother – who is nameless – from the Old English poem Beowulf.

There were deceiving femme fatales, such as the Sirens who lured sailors to shipwreck, tragic mistresses, including Dido and Cleopatra and poor, resourceful girls like Gretel in traditional fairy-tales.

These enduring archetypes have been customised and reimagined by each succeeding generation. Chaucer’s Wife of Bath is full of worldly wisdom and Shakespeare presented women who were wily and devious like Portia and Lady Macbeth as well as tricked and deceived like Juliet and Desdemona.

Victorian heroines like George Eliot’s Dorothea Brooke claimed their right to passion and equality – and in the 20th century female characters engaged with the world of work as well as matters of the heart, battling for self-determination. The eponymous heroine of Muriel Spark’s The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie is one example, setting out to impose her will on her impressionable students, though she is ultimately betrayed.

So where do we find ourselves now? One notable characteristic of the modern heroine is that her flaws are not only centre stage, they are celebrated. Jane Austen wondered if anyone but herself would like domineering Emma Woodhouse – but now every heroine worth her salt has as many vices as virtues. Women behaving badly fill the pages of books in every genre – from Katniss Everdene, the rebellious heroine of Suzannne Collins’ The Hunger Games to Frances Wray and Lilian Barber, the unlikely conspirators in Sarah Waters’ page-turning novel The Paying Guests.

There is also a recognition that female experience is as universal as male experience. The heroines of contemporary fiction reflect the rich diversity of female lives. Examples include Hortense Roberts, one of the main characters in Andrea Levy’s seminal novel Small Island who finds tenderness in her bleak new homeland, and Elizabeth Strout’s astonishing Olive Kitteridge, whose true complexity is revealed in a narrative that spans decades. Their everyday experiences are compelling and heartrending.

Genres are blending and heroines are complicated. They are morally ambiguous and their behaviour is unpredictable. The doomed mistress is fighting back and taking on the characteristics of the proxy witch. This is demonstrated by the typical heroine of the new crime sub-genre domestic noir which focuses on women’s experience and emotions in the home and workplace. She may find herself married to the modern equivalent of Bluebeard, but he is unlikely to get away with murder. This is exemplified in novels like Gone Girl – Amy Dunne outsmarts her husband and excels in trickery, cunningly creating mantraps while seeming to be the perfect wife.

Publishing’s latest passion is for redemptive, feel-good fiction, known as “up-lit”, and this also reinterprets existing tropes. Gail Honeyman’s lonely Eleanor Oliphant hits the vodka behind closed doors and attempts to conceal her dysfunctionality and traumatic childhood from the world, but is stronger and more able to grow than we first realise. One of the reasons for Eleanor’s wide appeal may be that she springs from a line of literary heroines – that of the spirited outsider.

Honeyman draws parallels between Eleanor and Jane Eyre, another abandoned child who finds her own path. Readers are engaged not only by Eleanor’s predicament, but by her determination to transcend disaster. Her most recent antecedent is Helen Fielding’s Chardonnay-swilling Bridget Jones, who is herself the direct descendant of Jane Austen’s best-loved heroine, Elizabeth Bennet.

Women who make their own rules are selling well in literary fiction too. In Conversations with Friends, Sally Rooney’s young Bohemians Frances and Bobbi are brimming with anarchic attitude, sharing “a contempt for the cultish pursuit of male physical dominance” and luxuriating in “shallow misery”. They lead unapologetically experimental lives, creating ripples of sexual confusion.

Following the various cases of male bullying and sexual harassment that have hit the headlines, it seems that fictional heroines reflect a mood of noncompliance with the world that men have organised. The 21st-century heroine may be scarred, imperfect or absurd. True love may be on the cards, but so might illicit sex. And while she may change in the course of the narrative, revealing strengths and strategies that surprise us, conformity is optional. Here’s to the good/bad heroine, long may she remain unredeemed.![]()

Sally O’Reilly, Lecturer in Creative Writing, The Open University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.