The link below is to an article that looks at decluttering books – yes, another one.

For more visit:

https://www.latimes.com/books/jacketcopy/la-ca-jc-goodbye-stuff-books-20170511-htmlstory.html

The link below is to an article that looks at decluttering books – yes, another one.

For more visit:

https://www.latimes.com/books/jacketcopy/la-ca-jc-goodbye-stuff-books-20170511-htmlstory.html

The link below is to an article that takes a look at letting go of books. This all seems a little unsettling to me 🙂

For more visit:

https://www.readitforward.com/essay/article/let-go-of-your-books/

The link below is to an article with some suggestions on a ‘Goodreads’ for kids.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2019/01/10/goodreads-for-kids-alternatives/

The link below is to an article that provides 8 ideas for what to do with unwanted books.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2019/01/10/repurpose-unwanted-books/

The link below is to an article reporting on the winner of the 2019 PEN/Nabokov Award for International Literature – Sandra Cisneros.

For more visit:

https://www.latimes.com/books/la-et-jc-sandra-cisneros-pen-nabokov-award-20190205-story.html

Camilla Nelson, University of Notre Dame Australia

In this series, we look at under-acknowledged women through the ages.

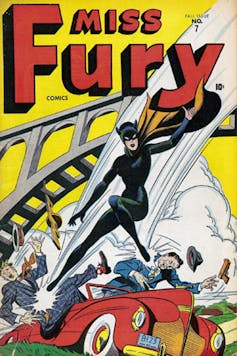

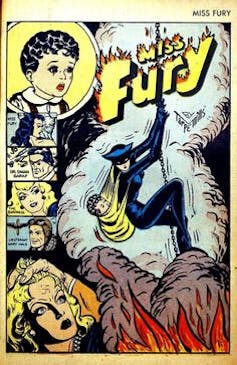

In April 1941, just a few short years after Superman came swooping out of the Manhattan skies, Miss Fury – originally known as Black Fury – became the first major female superhero to go to print. She beat Charles Moulton Marsden’s Wonder Woman to the page by more than six months. More significantly, Miss Fury was the first female superhero to be written and drawn by a woman, Tarpé Mills.

Miss Fury’s creator – whose real name was June – shared much of the gritty ingenuity of her superheroine. Like other female artists of the Golden Age, Mills was obliged to make her name in comics by disguising her gender. As she later told the New York Post, “It would have been a major let-down to the kids if they found out that the author of such virile and awesome characters was a gal.”

Yet, this trailblazing illustrator, squeezed out of the comic world amid a post-WW2 backlash against unconventional images of femininity and a 1950s climate of heightened censorship, has been largely excluded from the pantheon of comic greats – until now.

Comics then and now tend to feature weak-kneed female characters who seem to exist for the sole purpose of being saved by a male hero – or, worse still, are “fridged”, a contemporary comic book colloquialism that refers to the gruesome slaying of an undeveloped female character to deepen the hero’s motivation and propel him on his journey.

But Mills believed there was room in comics for a different kind of female character, one who was able, level-headed and capable, mingling tough-minded complexity with Mills’ own taste for risqué behaviour and haute couture gowns.

Where Wonder Woman’s powers are “marvellous” – that is, not real or attainable – Miss Fury and her alter ego Marla Drake use their collective brains, resourcefulness and the odd stiletto heel in the face to bring the villains to justice.

And for a time they were wildly successful.

Miss Fury ran a full decade from April 1941 to December 1951, was syndicated in 100 different newspapers at the height of her wartime fame, and sold a million copies an issue in reprints released by Timely (now Marvel) comics.

Pilots flew bomber planes with Miss Fury painted on the fuselage. Young girls played with paper doll cut outs featuring her extensive high fashion wardrobe.

Miss Fury’s “origin story” offers its own coolly ironic commentary on the masculine conventions of the comic genre.

One night a girl called Marla Drake finds out that her friend Carol is wearing an identical gown to a masquerade party. So, at the behest of her maid Francine, she dons a skin tight black cat suit that – in an imperial twist, typical of the period – was once worn as a ceremonial robe by a witch doctor in Africa.

On the way to the ball, Marla takes on a gun-toting killer, using her cat claws, stiletto heels, and – hilariously – a puff of powder blown from her makeup compact to disarm the villain. She leaves him trussed up with a hapless and unconscious police detective by the side of the road.

Miss Fury could fly a fighter plane when she had to, jumping out in a parachute dressed in a red satin ball gown and matching shoes. She was also a crack shot.

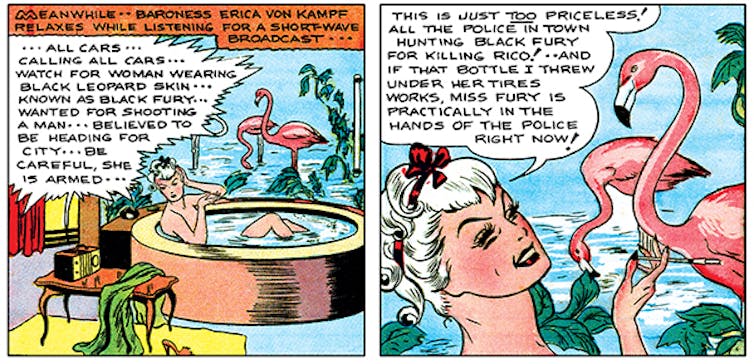

This was an anarchic, gender flipped, comic book universe in which the protagonist and principle antagonists were women, and in which the supposed tools of patriarchy – high heels, makeup and mermaid bottom ball gowns – were turned against the system. Arch nemesis Erica Von Kampf – a sultry vamp who hides a swastika-branded forehead behind a v-shaped blond fringe – also displayed amazing enterprise in her criminal antics.

Invariably the male characters required saving from the crime gangs, the Nazis or merely from themselves. Among the most ingenious panels in the strip were the ones devoted to hapless lovelorn men, endowed with the kind of “thought bubbles” commonly found hovering above the heads of angsty heroines in romance comics.

By contrast, the female characters possessed a gritty ingenuity inspired by Noir as much as by the changed reality of women’s wartime lives. Half way through the series, Marla got a job, and – astonishingly, for a Sunday comic supplement – became a single mother, adopting the son of her arch nemesis, wrestling with snarling dogs and chains to save the toddler from a deadly experiment.

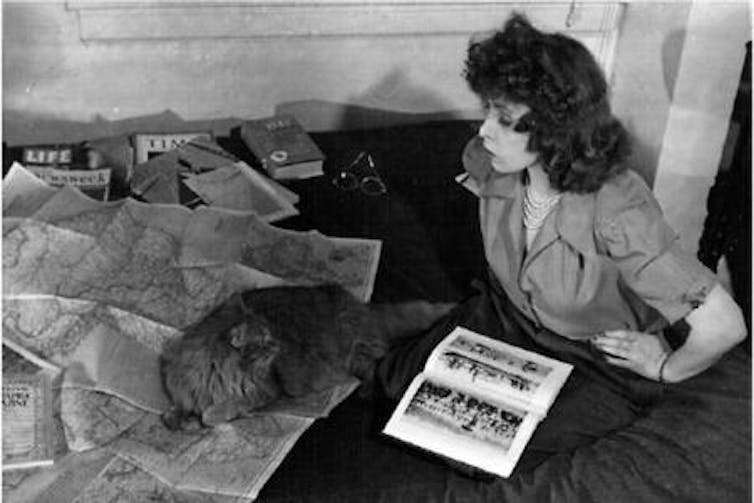

Mills claims to have modelled Miss Fury on herself. She even named Marla’s cat Peri-Purr after her own beloved Persian pet. Born in Brooklyn in 1918, Mills grew up in a house headed by a single widowed mother, who supported the family by working in a beauty parlour. Mills worked her way through New York’s Pratt Institute by working as a model and fashion illustrator.

In the end, ironically, it was Miss Fury’s high fashion wardrobe that became a major source of controversy.

In 1947, no less than 37 newspapers declined to run a panel that featured one of Mills’ tough-minded heroines, Era – a South American Nazi-Fighter who became a post-war nightclub entertainer – dressed as Eve, replete with snake and apple, in a spangled, two-piece costume.

This was not the only time the comic strip was censored. Earlier in the decade, Timely comics had refused to run a picture of the villainess Erica resplendent in her bath – surrounded by pink flamingo wallpaper.

But so many frilly negligées, cat fights, and shower scenes had escaped the censor’s eye. It’s not a leap to speculate that behind the ban lay the post-war backlash against powerful and unconventional women.

In wartime, nations had relied on women to fill the production jobs that men had left behind. Just as “Rosie the Riveter” encouraged women to get to work with the slogan “We Can Do It!”, so too the comparative absence of men opened up room for less conventional images of women in the comics.

Once the war was over, women lost their jobs to returning servicemen. Comic creators were no longer encouraged to show women as independent or decisive. Politicians and psychologists attributed juvenile delinquency to the rise of unconventional comic book heroines and by 1954 the Comics Code Authority was policing the representation of women in comics, in line with increasingly conservative ideologies. In the 1950s, female action comics gave way to romance ones, featuring heroines who once again placed men at the centre of their existence.

Miss Fury was dropped from circulation in December 1951, and despite a handful of attempted comebacks, Mills and her anarchic creation slipped from public view.

Mills continued to work as a commercial illustrator on the fringes of a booming advertising industry. In 1971, she turned a hand to romance comics, penning a seven-page story that was published by Marvel, but it wasn’t her forte. In 1979, she began work on a graphic novel Albino Jo, which remains unfinished.

Despite her chronic asthma, Mills – like the reckless Noir heroine she so resembled – chain-smoked to the bitter end. She died of emphysema on December 12, 1988, and is buried in New Jersey under the simple inscription, “Creator of Miss Fury”.

This year Mills’ work will be belatedly recognised. As a recipient of the 2019 Eisner Award, she will finally take her place in the Comics Hall of Fame, alongside the male creators of the Golden Age who have too long dominated the history of the genre. Hopefully this will bring her comic creation the kind of notoriety, readership and big screen adventures she thoroughly deserves.![]()

Camilla Nelson, Associate Professor in Media, University of Notre Dame Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Dominique Boullier, Sciences Po – USPC; Mariannig Le Béchec, Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, and Maxime Crépel, Sciences Po – USPC

We stand amazed by the vitality of printed books, a more than 500-year-old technique, both on and offline. We have observed over the years all of the dialogue which books have created around themselves, through 150 interviews with readers, bookshops, publishers, bloggers, library assistants, 25 participant observations, 750 responses to an online questionnaire and 5,000 mapped sites in France and the francophone world. An impressive collective activity. So, yes, your book carries on living just by staying on your shelf because you talk about it, remember it, and refer to it in conversation. Even better still, you might have lent it to a friend so that she can read it, perhaps you have spent time with people who have spoken about it before buying it, or after having read it. You will have encountered official reviews, of course, and also blogs about it. The conversation goes on even when the book is no longer in circulation.

What first struck us was the very active circulation of books in print, compared with digital versions which do not spread so well. Once a book has been sold either in a bookshop or through an online platform, it has multiple lives. It can be loaned, given as a present, but also sold on second-hand, online or in specialist shops. And it can go full circle and be resold, such journeys made in a book’s life are rarely taken into account by the overall evaluation of the publication.

The application Bookcrossing allows you to follow books that we “abandon” or “set free” by chance in public places so that strangers take possession of and, then, you hope, get in touch to keep track of the book’s journey. Elsewhere, the book will be left in an open-access “book box” which have popped up across France and other countries. Some websites have become experts in selling second-hand books like Recyclivre, which uses Amazon to gain visibility.

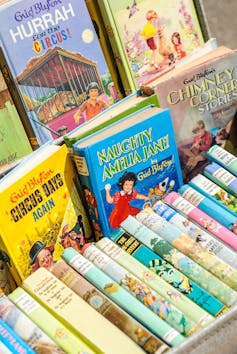

Yard sales, antiques fairs, book markets give a new lease of life to countless books which remained forgotten because they were a quick one-time read. The book as a material object, regardless of its age, retains an unequalled sensorial pleasure, and brings with it special memories, bygone times, a sacred piece of craftsmanship with its fragile bindings, or, the nostalgia offered by children’s books or fairy tales.

Whole professions are dedicated to the web, and increasingly so, since it first came into existence. This has turned the second life of books and the recycling of them into a money-making machine for online retailers, and as a result books are kept alive. Some people have become eBay sellers, experts only thanks to the books they sell on this platform. Sometimes even, these books’ lives are extended by charity shops, such as Oxfam. At some stage however, there is only the paper left to give a book its value, once it has been battered and recycled.

One would have thought that faced with the weight, volume, and physical space occupied by books in print, that the digital book ought to have wiped the floor with its print counterpart. This has been the case with online music, for example, which practically handed a death sentence to the CD, or for films on demand which have greatly shrunk the DVD market. However, for books, this simply has not happened. In the United States like in France, the market for online books never surpasses the 20% mark of the sales revenues of books in print. And that is without including the sales revenue of the second-hand book market as we previously mentioned. The digital book seldom goes anywhere once purchased, due to controls imposed on the files by digital-rights management (DRM) and the incompatibility of their formats on other digital devices (Kindle and others).

Our interviews revealed the pleasure of giving books as presents, but also of lending them. The exchange of the physical item with its cover, size and unique smell bring much more satisfaction than if a well-meaning friend offers you digital book files on a USB stick containing… a thousand files already downloaded! Indeed, the latter will seldom ever be considered a present but rather a simple file transfer, equivalent to what we do several times a day at work. This also gives rights holders reasons to thus decry “not paying is theft”, in this case the gift of files would also become theft.

Bloggers who exchange books as presents (bookswapping) show that goodwill prevails and puts stress on the backburner. This is done on the condition that the book is personalised in some way: a poignant quote, a meaningful object associated in some way with the book (cakes for example!), and the surprise of receiving a completely random gesture of kindness.

What travels even better than books are conversations, opinions, critiques, recommendations. Some discussions are created within or around reading groups or in dedicated forums online such as the Orange Network Library, for example. There are recommended reading lists, readers’ ratings, and book signings with authors are organised. These networks are digital, but they existed well before the Internet, and they remain dynamic today.

However, the rise of blogs at the start of the 2000s led to an increase in the number of reviews by ordinary people. This provided visibility, even a reputation for some bloggers. Of course, institutional and newsworthy reviews continue to play their role in guiding the masses, and they are influential prescribers protected by publishers. But websites like Babelio, combine a popular expertise, shared and distributed among many bloggers who are sometimes very specialised themselves. The website was created in 2007 and has over 690,000 reader members.

The proliferation of content and publications can easily disorientate us; the role of these passionate bloggers, who are often experts in given literary fields, becomes important because they are “natural” influencers one might say, as they are the closest to the public. However, some publishers have understood the benefits of working with these bloggers, especially in so far as concerns specialist genres like manga, comics, crime novels or youth fiction. Sometimes a blogger, YouTuber and web writer is published like Nine Gorman.

Some bookshops contribute even more directly in coordinating these bookworms, they “mould” their audience, or at least they support the books both online and in their shops with face-to-face meetings. Conversation is a unifying force for fans who are undoubtedly the best broadcasters across a broad sphere.

Platforms encourage readers to expand their domain, in the guise of fanfictions, which are published online by the author or his readers. The relationship with authors is closer than ever and is much more direct, the same can be said of the music industry. On particular platforms like Wattpad, texts which are made available are linked with collective commentary.

But above all, the dialogue about reading has often been transformed into writing itself. It might be published on a blog and may be likened to authorial work but at the other end of the spectrum, it might be something modest like the annotations one leaves in their own book. These annotations, more common in non-fiction texts, can form a sort of trade. For example if you lend or sell on a book, which is also stocked and shared with the online systems of Hypothes.is, it allows any article found on the web to be annotated, and the comments saved independent to the display format of the article. This makes it easier to organise readers into groups.

Printed books have in fact become digital through the use of digital platforms which allow them to be circulated as an object or as conversations about the book. The collective attention paid creates a permanent and collaborative piece of work, very different to frenetic posts on social media. Readers take their time to read, a different type of engagement altogether to social media’s high frequency, rapid exchanges. The combination of these differently paced interactions can, though, encourage one just to read through alerts from social media posts then followed by a longer form of reading.

Networks formed by books constitute as well a major resource for attracting attention. This is still not a substitute for the effects of “prize season” which guides the mass readership, but which deserves to be considered more critically, given the fact that publishers increasingly take advantage of these active communities.

It would thus be possible to think of the digital book as part of the related book ecosystem, rather than treating it as just a clone. To call it homothetic, is to say that it is an exact recreation of the format and properties of the book in print in a digital format. Let’s imagine multimedia books connected to, and permanently engaged with, the dialogue surrounding the book – this would be something else entirely, affording added value which would justify the current retail price for simple files. This would therefore be an “access book” and which would perhaps attract a brand new audience and above all it would widen this collective creativity already present around books in print.

Dominique Boullier, Mariannig Le Béchec and Maxime Crépel are the authors of “The book exchange: Books’ lives and readers’ practices.”![]()

Dominique Boullier, Professeur des universités en sociologie, Sciences Po – USPC; Mariannig Le Béchec, Maître de Conférences en Sciences de l’Information et de la Communication, Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, and Maxime Crépel, Sociologue, ingénieur de recherche au médialab de Sciences Po, Sciences Po – USPC

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Helen Joanne Adam, Edith Cowan University

A lack of diverse books is failing children from minority backgrounds. This is something that should concern all Australians.

I studied five Australian early learning settings and found less than 5% of books contained cultural diversity. My more recent findings show educators are struggling to use books in ways that promote intercultural understandings.

Read more:

Eight Australian picture books that celebrate family diversity

Diverse books can help achieve principles of diversity written into Australian education polices. The potential of diverse books in addressing these principles and equity more generally is too important to ignore.

Reading to children has a powerful impact on their academic and intellectual development. Children learn about themselves and the world through the books they’re exposed to. Importantly, children can learn understanding and respect for themselves and for those who are different to them.

But a lack of diverse books means we have a serious problem. Currently, children from minority backgrounds rarely see themselves reflected in the books they’re exposed to. Research over the last two decades shows the world presented in children’s books is overwhelmingly white, male and middle class.

For children from minority groups, this can lead to a sense of exclusion. This can then impact on their sense of identity and on their educational and social outcomes.

The evidence regarding Indigenous groups across the world is even more alarming. Research shows these groups are rarely represented. And, if represented at all, are most likely to be represented in stereotypical or outdated ways.

Many educators or adults unwittingly promote stereotypical, outdated or exotic views of minority groups. This can damage the outcomes for children from those groups. Children from dominant cultural groups can view themselves as “normal” and “others” as different.

Read more:

How children’s picturebooks can disrupt existing language hierarchies

In my recent study, I found the book collections in early childhood settings were overwhelmingly monocultural. Less than 5% of the books contained any characters who were not white. And in those few books, the minority group characters played a background role to a white main character.

Particularly concerning was the lack of representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Of 2,377 books, there were only two books available to children that contained Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander characters. Only one of these was a story book.

In this book, the Aboriginal character was portrayed as a semi-naked person playing a didgeridoo in the outback. There were no books showing actual everyday lifestyles or views of Aboriginal people.

The accompanying practice of teachers may also be counterproductive to achieving equitable outcomes for children from minority backgrounds. The teachers in my study were keen and committed to the children in their care. They were passionate about the importance of reading to children. But when it came to selecting books, they struggled to know what books to select and how best to use them.

Other research has found similar uncertainty among teachers. Some teachers overlooked the importance of diversity altogether. Some saw diversity as a special extra to address occasionally rather than an essential part of everyday practice.

The call for more diverse booksfor children is gaining momentum around the world. The value of diverse books for children’s educational, social and emotional outcomes is of interest to all.

The voices of Aboriginal and minority group writers calling for change are gaining momentum. But there is still much to be done.

The recent development of a database from the National Centre for Australian Children’s Literacy is an important step. Publications of diverse books are still very much in the minority but some awareness and promotion of diverse books is increasing.

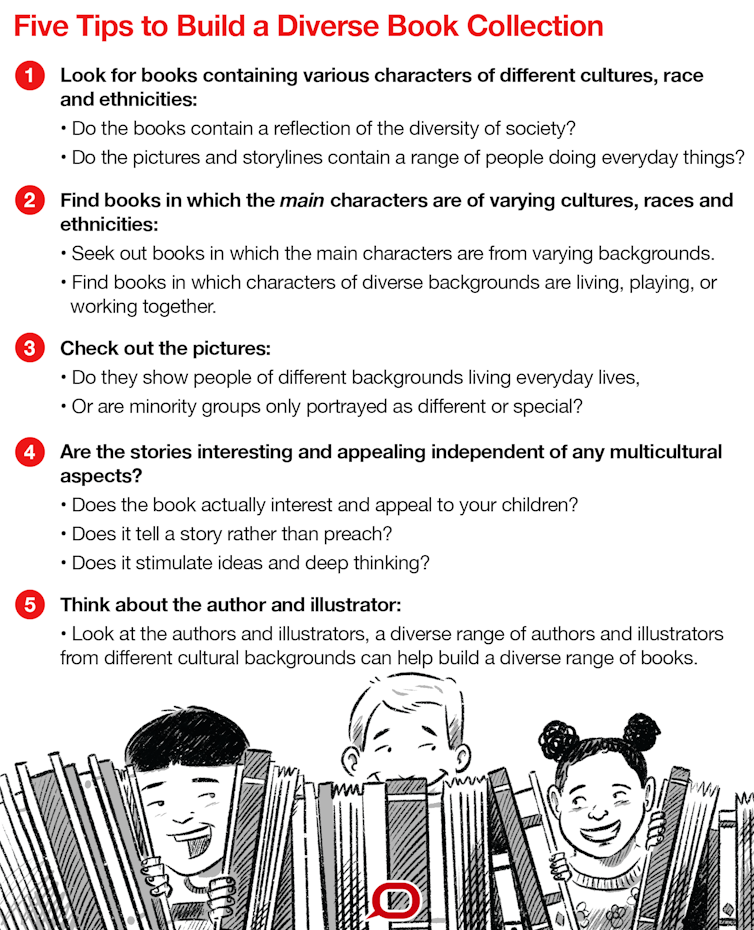

These important steps forward could be supported with better training for teachers and increased discussion among those who write, publish and source books for children. Here are five tips to help you build a more diverse book collection.

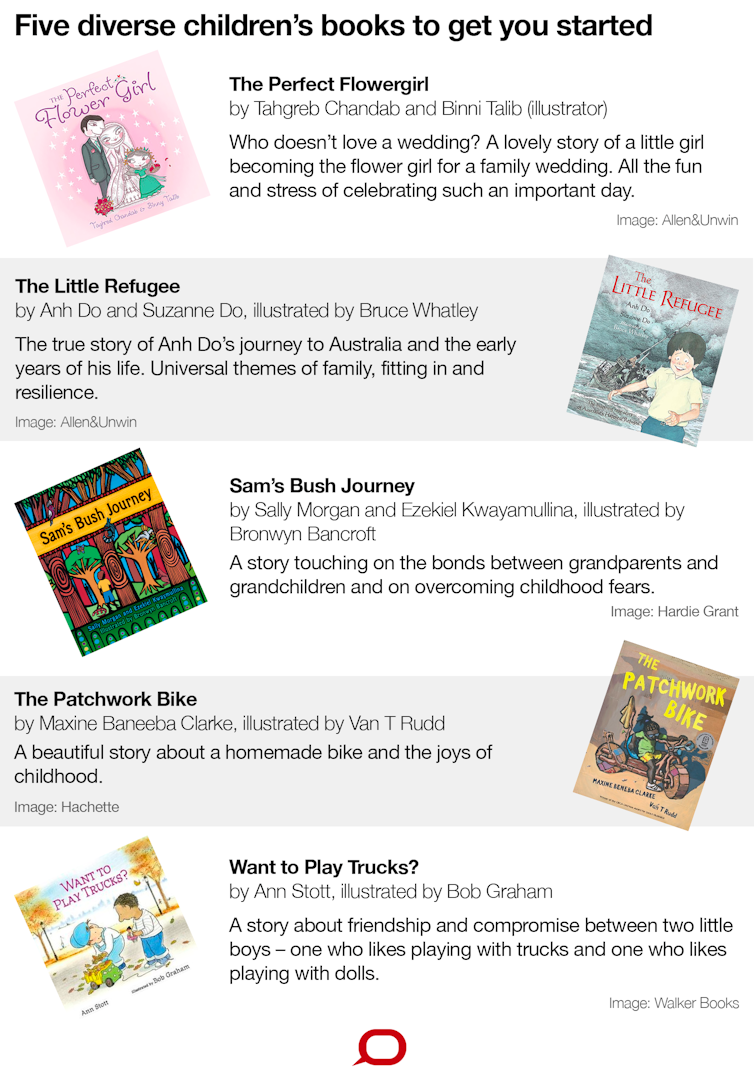

Educators and parents can strive to create libraries of inclusive books. This can ensure every child has the opportunity to achieve the substantial benefits we know books can bring. Here are five book titles to get you started on building a more diverse collection of books.

When we share diverse books with children, they gain opportunities to see themselves reflected and affirmed. Importantly we broaden children’s perspectives and understandings of those that are different to themselves.

Read more:

Telling the real story: diversity in young adult literature

This supports children to value others as unique and equal individuals.

Inclusive book collections which depict and affirm a diverse range of children, will contribute to equitable outcomes for all children.![]()

Helen Joanne Adam, Lecturer in Literacy Education and Children’s Literature, Edith Cowan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article reporting on the big winner at the Victorian Prize for Literature and the Victorian Premier’s Literary Awards for 2019… and he wasn’t allowed to attend.

You must be logged in to post a comment.