Helen Keller: A Life From Beginning to End by Hourly History

Helen Keller: A Life From Beginning to End by Hourly History

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

Monthly Archives: November 2018

Various Book Repair Tutorials

Not My Review: Forgotten Realms – The Dark Elf Trilogy by R. A. Salvatore

Not My Review: Throne of Glass (Book 7) – Kingdom of Ash by Sarah J. Maas

Not My Review: She Has Her Mother’s Laugh by Carl Zimmer

Shortlist for the 2018 Diagram Prize

The link below is to an article that takes a look at the shortlist for the 2018 Diagram Prize for the oddest book title.

For more visit:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/oct/26/the-joy-of-waterboiling-is-hot-tip-for-oddest-book-title-prize

Reading and Depression

The link below is to an article that takes a look at reading and depression – does reading help?

For more visit:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2018/oct/26/just-how-helpful-is-reading-for-depression

Bibliotherapy: how reading and writing have been healing trauma since World War I

Viacheslav Nikolaenko via Shutterstock

Sara Haslam, The Open University; Edmund King, The Open University, and Siobhan Campbell, The Open University

Bibliotherapy – the idea that reading can have a beneficial effect on mental health – has undergone a resurgence. There is mounting clinical evidence that reading can, for example, help people overcome loneliness and social exclusion. One scheme in Coventry allows health professionals to prescribe books to their patients from a list drawn up by mental health experts.

Even as public library services across Britain are cut back, the healing potential of books is increasingly recognised.

The idea of the healing book has a long history. Key concepts were forged in the crucible of World War I, as nurses, doctors and volunteer librarians grappled with treating soldiers’ minds as well as bodies. The word “bibliotherapy” itself was coined in 1914, by American author and minister Samuel McChord Crothers. Helen Mary Gaskell (1853-1940), a pioneer of “literary caregiving”, wrote about the beginnings of her war library in 1918:

Surely many of us lay awake the night after the declaration of War, debating … how best we could help in the coming struggle … Into the mind of the writer came, like a flash, the necessity of providing literature for the sick and wounded.

The well-connected Gaskell took her idea to the medical and governmental authorities, gaining official approval. Lady Battersea, a close friend, offered her a Marble Arch mansion to store donated books, and The Times carried multiple successful public appeals. As Gaskell wrote:

What was our astonishment when not only parcels and boxes, but whole libraries poured in. Day after day vans stood unloading at the door.

Gaskell’s library was affiliated to the Red Cross in 1915 and operated internationally – with depots in Egypt, Malta, and Salonika. Her operating principles, axiomatic to bibliotherapy, were to provide a “flow of comfort” based on a “personal touch”. Gaskell explained that “the man who gets the books he needs is the man who really benefits from our library, physically and mentally”.

Her colleagues running Endell Street Military Hospital’s library shared similar views about the importance of books in wartime. On August 12, 1916, the Daily Telegraph reported on the hospital, calling the library a “story in itself”. Run by novelist Beatrice Harraden, a member of the Womens Social and Political Union and also, briefly, the actress and feminist playwright Elizabeth Robins, the library was a fundamental part of the treatment of 26,000 wounded between 1915 and 1918.

“We learned,” Robins wrote in Ancilla’s Share, her 1924 analysis of gender politics, “that the best way, often the only way, to get on with curing men’s bodies was to do something for their minds.”

The books the men wanted first were likely to be by the ex-journalist and popular writer Nat Gould, whose novels about horseracing were bestsellers. Otherwise, fiction by Rudyard Kipling, Marie Corelli, or Robert Louis Stevenson rated highly. In the Cornhill Magazine in November, 1916, Harraden revealed that the librarians’ “pilgrimages” from one bedside to another ensured what she called “good literature” was always within reach, but that the book that would “heal” was the one that was most wanted:

However ill [a patient] was, however suffering and broken, the name of Nat Gould would always bring a smile to his face.

The literary caregivers at Endell Street worked responsively, and without judgement, a crucial legacy.

Library on the frontline

Literary caregiving also took place closer to the front. Throughout the war, the YMCA operated a network of recreation huts and lending libraries for soldiers. After losing his only son, Oscar, at Ypres, the author E. W. Hornung offered his services to the YMCA. Hornung – a relatively obscure figure now, but a literary celebrity then – authored the “Raffles” stories about the gentleman thief of the same name.

Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums

Arriving in France in late 1917, Hornung was initially put to work serving tea to British soldiers. But the YMCA soon found him a more suitable job, placing him in charge of a new lending library for soldiers in Arras. Dispensing tea and books to soldiers helped him process his grief. Hearing soldiers talk about their favourite books played a key role in his recovery – but he also sincerely believed that reading helped soldiers keep their minds healthy while they were in the trenches. Hornung wrote in 1918 that he wanted to feed “the intellectually starved”, while “always remembering that they are fighting-men first and foremost, and prescribing for them both as such and as the men they used to be”.

Writing a new future

Present-day veterans encounter the potential of reading and writing in equally participatory ways as interventions with the charities Combat Stress UK (CSUK) and Veterans’ Outreach Services demonstrate.

In CSUK, we read widely from contemporary work before undertaking writing exercises. These were designed to help provide detachment from the internal repetition of traumatic stories that some with PTSD experience. The director of therapy at CSUK, Janice Lobban, says:

Collaborative work … gave combat stress veterans the valuable opportunity of developing creative writing skills. Typically, the clinical presentation of veterans causes them to avoid unfamiliar situations and the loss of self-confidence can affect the ability to develop creative potential. Workshops within the safety of our Surrey treatment centre enabled veterans to have the confidence to experiment with new ideas.

Another approach, in workshops with Veterans’ Outreach Support in Portsmouth in 2018, explored the role of writing in training veterans to become “peer-mentors” of other veterans wanting to access VOS services, ranging from physical and mental wellness to housing benefits to job-seeking.

The results show that veterans responded positively to opportunities for imaginative writing. Trainee peer-mentors responding to a questionnaire told us that the exercises helped them to write fluently about their own lives. For people who spend so much time filling out forms to access various benefits, the opportunity to write creatively was seen as a liberating experience. As one veteran put it: “We are writing into ourselves”.

For 100 years now, reading and writing have helped veterans build relationships, gain confidence and face the challenges of their post-service lives. Our current research charts the influence of wartime literary caregiving on contemporary practice.![]()

Sara Haslam, Senior Lecturer in English, The Open University; Edmund King, Lecturer in English, The Open University, and Siobhan Campbell, Lecturer of Creative Writing, The Open University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Not My Review: Shadow Club (Book 1) – The Shadow Club by Neal Shusterman

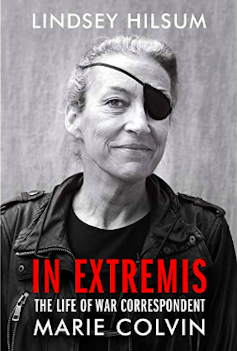

Marie Colvin: Lindsey Hilsum’s revealing biography of courageous war reporter is compelling stuff

Wikipedia

Idrees Ahmad, University of Stirling

For Marie Colvin, it was Lebanon’s War of the Camps that brought home the power of journalism. In April 1987 Burj al Barajneh, a Palestinian refugee camp, was besieged by Amal, a Shia militia backed by the Syrian regime.

Colvin and her photographer Tom Stoddart paid an Amal commander to briefly hold fire while they ran into the camp across no-man’s land. The assault on the camp was relentless and women were forced to run a gauntlet of sniper fire to get food and water for their families.

One young woman, Haji Achmed Ali, was shot as she tried to re-enter the camp with supplies. As she lay there wounded, no man dared pull her to safety. But then, Colvin reported:

Two [women] raced from cover, plucked Achmed Ali from the dust and hauled her to safety. It is the women who are dying and it was women who tired of men’s inaction.

Despite the best efforts of volunteer medics, Achmed Ali would not survive. At the hospital another woman appealed to Colvin to tell the world the young woman’s story.

Penguin

War on Women, the powerful piece Colvin wrote, was splashed across the front page of the Sunday Times on 5 April 1987. “The facts were clear and brutal,” writes Lindsey Hilsum in In Extremis: The Life of War Correspondent Marie Colvin, “as Marie had seen it with her own eyes”.

The effect was almost immediate. Three days later the Syrian regime ordered its proxy militia to stand down and for the first time the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) was able to enter the camp. A herd of journalists soon followed. “In a few days the War of the Camps was over,” writes Hilsum.

Complexity

In Extremis is Hilsum’s riveting story of how Colvin went from a carefree idealistic youth in Oyster Bay, NY, to an audacious war correspondent who reported from sites of merciless violence in Lebanon, Palestine, Chechnya, East Timor, Sri Lanka, the Balkans and Libya. Until her death at the hands of the Syrian regime, Colvin remained indefatigable, never losing her idealism or youthful energy.

By eschewing hagiography for complexity, Hilsum has created a captivating portrait. The Colvin that Hilsum reveals is shaped by the loss of a beloved father, by the spirit of competition, by being a woman in a male-dominated field, and, above all, by a moral commitment to bearing witness and a natural affinity for the underdog.

By casting Colvin’s triumphs against the demons that pursued her – the turbulence of failed romances, the struggles with alcohol, the traumas of war – Hilsum gives a truer sense of the challenges that she faced. By capturing Colvin’s vivacity, generosity, humour and affability, Hilsum also shows how this inveterate raconteur came to be loved and admired in equal measure.

Like Ernest Hemingway, Colvin had invested in her own legend and sometimes strained to live up to it. But there was nothing inauthentic about her capacity for empathy or her commitment to the truth. Though in times of peace she struggled to distinguish herself, in times of crisis she unfailingly outshone her peers. While the Middle East remained her main beat, she also ventured farther afield, from Chechnya to Sri Lanka and East Timor.

But if East Timor was the site of her greatest triumph (her defiant refusal to abandon trapped refugees eventually led to their safe evacuation), Sri Lanka became the site of her greatest trauma, losing an eye to a soldier’s grenade while returning from a visit to the Tamil-controlled north. But while the trauma would haunt her and briefly sapped her confidence, she remained undeterred. She courted greater danger in subsequent years and turned the eye-patch into part of her legend.

The making of a legend

By the time Colvin entered Syria in 2012, the reporting landscape had changed. Israel and Putin’s Russia had demonstrated that journalists could be targeted with impunity and killers elsewhere had taken note. Before Colvin entered the besieged Syrian enclave of Baba Amr with photographer Paul Conroy, they had been warned that regime soldiers had orders to summarily execute journalists found in the area.

But Colvin and Conroy agreed that the story was worth the risk; they crawled through three kilometres of a drainage pipe to infiltrate. They found Baba Amr’s only functioning hospital inundated with the dead and the dying; they met nearly 150 widows and orphans in a crowded basement sheltering from the regime’s shelling. Widows’ Basement, Colvin’s haunting last story for the Sunday Times, was also her most poignant.

What happened next fused Colvin’s life and legend and placed her convictions beyond any cynic’s doubt. Five days before her death, Colvin had made it safely out of Baba Amr. But having seen what she had seen, she felt a moral compulsion to return. Conroy had misgivings, but he shared Colvin’s sense of commitment.

The regime meanwhile had tightened the siege and an informer had alerted it to the journalists’ presence. Colvin was conscious of the risks but made a fateful choice: hoping that her reporting would once again stir the international community into restraining a killer, she spoke to the BBC and CNN, emphasising the urgency of the situation. The regime used the signal from her satellite phone to pinpoint her location and killed her with artillery. The regime would lay many more sieges and no western journalist would dare enter another.

At a 2006 Frontline Club (a London hub for foreign correspondants) event about the killing of Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya, Colvin interrupted the panellists’ abstract digressions and encouraged everyone to ask the more pertinent question:

Who killed Anna? That’s the best thing we can do … That’s what we can do as journalists.

Now Colvin’s family is trying to establish the same about her killers. And this is also the best thing we can do as citizens: support the investigation and ensure that Colvin’s killers don’t enjoy the impunity that Politkovskaya’s did. Until we resolve to protect our truthtellers, truth will remain fragile and justice will be denied.

For all her emotional turmoil, personal flaws and misjudgements, Colvin was an exemplary friend, human being and journalist. She maintained an unwavering commitment to showing “humanity in extremis” – with truth, empathy and responsibility. Hilsum has written a book as compelling as its subject.![]()

Idrees Ahmad, Lecturer in Digital Journalism, University of Stirling

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.