The link below is to an article that takes a look at the winners of the 2018 Australian Book Industry Awards.

For more visit:

https://blog.booktopia.com.au/2018/05/04/abia-2018-winners/

The link below is to an article that takes a look at the winners of the 2018 Australian Book Industry Awards.

For more visit:

https://blog.booktopia.com.au/2018/05/04/abia-2018-winners/

The link below is to an article that takes a look at cli-fi.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2018/05/03/climate-fiction/

The links below are to articles reporting on the canceling of the 2018 Nobel Prize for Literature.

For more visit:

– https://bookriot.com/2018/05/04/news-the-nobel-prize-in-literature-2018-cancelled-in-the-wake-of-metoo/

– https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/may/04/nobel-prize-for-literature-2018-cancelled-after-sexual-assault-scandal

– https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/may/04/nobel-literature-prize-postponement-attempts-to-retain-some-dignity

The link below is to a book review of ‘The Gospel Comes with a House Key,’ by Rosaria Champagne Butterfield.

For more visit:

http://matt-mitchell.blogspot.com.au/2018/04/book-review-gospel-comes-with-house-key.html

The link below is to a book review of ‘Rejoicing in Lament: Wrestling with Incurable Cancer and Life in Christ,’ by J. Todd Billings.

For more visit:

http://matt-mitchell.blogspot.com.au/2018/04/book-review-rejoicing-in-lament.html

Emmett Stinson, Deakin University

It has been a big 12 months for Australian small publishers, who have swept what are arguably the three most important national literary awards. Sydney press Giramondo published Alexis Wright’s biography Tracker, winner of the 2018 Stella Prize; Melbourne’s Black Inc. published Ryan O’Neill’s Their Brilliant Careers, which won the 2017 Prime Minister’s Literary Award for Fiction; and Josephine Wilson’s Extinctions (University of Western Australia Publishing) won the 2017 Miles Franklin Literary Award.

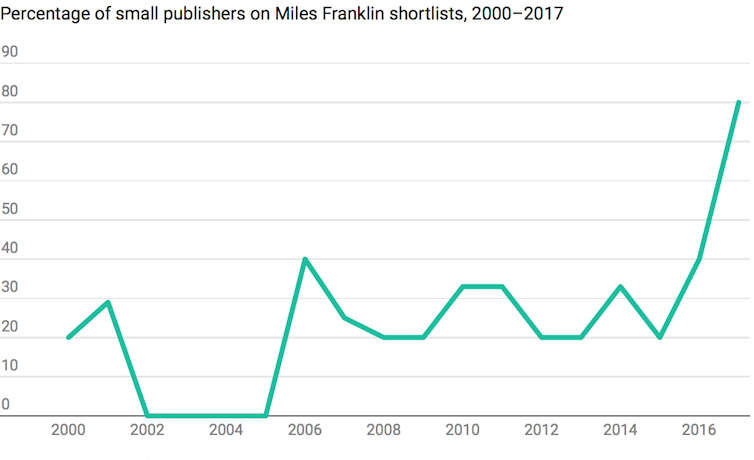

Another work from a small publisher, A. S. Patric’s Black Rock White City (Transit Lounge) also won the Miles Franklin in 2016. Small publishers have dominated these awards’ shortlists as well, comprising 80% of the shortlisted titles for the last Miles Franklin and Prime Minister’s awards and 66% of the shortlisted titles for the last Stella.

This is a significant reversal: these awards have historically been dominated by large publishers. Since 2000, for example, only 21% of shortlisted titles for the Miles Franklin have been published by small publishers.

There are dozens of important and respected Australian literary prizes, which help to solidify authors’ reputations and subsidise their writing (this is not an exaggeration; as Bernard Lahire has demonstrated through sociological surveys in France even most “successful” authors draw the majority of their income through other, and often unrelated, work).

But these three awards — the Stella, the Miles Franklin, and the Prime Minister’s — are particularly important because they have broader recognition among the media and the reading public. These three prizes not only increase authors’ and publishers’ status within the literary field but also tend to increase book sales. This is particularly important for smaller publishers, where one successful book can cross-subsidise the publication of many others.

Small publishers have a long history in Australia, and have played a culturally important role. Many of Australia’s most famous contemporary writers started out at small publishers. Peter Carey’s early books were all published by University of Queensland Press. Helen Garner’s Monkey Grip (1977) was published by the influential small publisher McPhee-Gribble, which launched the careers of many other notable writers before being wholly acquired by Penguin in 1989. While large multinationals dominated much of the market for Australian literary fiction in the 1980s and 1990s, small publishers started to become particularly important in Australian literature again in the 2000s.

There are many reasons why larger publishers have moved away from literary publishing, as Mark Davis discussed in his 2006 essay The Decline of the Literary Paradigm in Australian Publishing. As Davis argued, the big drivers of this change were increased competition and the rise of data-based decision making among publishers. With the appearance of book data provider Nielsen BookScan in Australia, publishers suddenly had good and fast data on what kinds of titles were selling and which weren’t.

Moreover, the rise of literary blockbusters in the 1990s, including series such as Harry Potter and, more recently, Twilight, has had a huge impact on the way publishers do their business. Blockbuster titles are worth an inordinate amount of the market. For example, Fifty Shades of Grey, at one point, sold one million copies in four days; a novel in Australia is usually considered successful if it sells 6,000 copies in total.

Not only do blockbusters sell in greater numbers, but the marginal costs associated with manufacturing books decrease as more are sold. For these reasons, large publishers have increasingly chased bestselling titles, rather than investing in literary works. The latter, although culturally important, rarely become blockbusters, unless they have won a major award or been adapted into a successful film or television series.

The retreat of large publishers from literary publishing is particularly visible in their virtually non-existent investments in low-selling but culturally significant forms, such as short stories or poetry. While large publishers occasionally publish high-profile collections of short stories, like Nam Le’s The Boat (Penguin, 2007) or Maxine Beneba Clarke’s Foreign Soil (Hachette, 2014), they rarely bring out more than one or two such collections per year. Large publishers have basically no investment whatsoever in contemporary poetry publishing. Australian poetry, in particular, is kept in circulation by a handful of small publishers, such as Giramondo, Cordite, UWA Publishing, Five Islands, and Puncher & Wattmann.

Large publishers’ withdrawal from these areas of literary publishing has also left space for smaller ones to flourish. On the one hand, it has meant that a number of well-known Australian writers have decided to publish their later works with smaller publishers. J.M. Coetzee, Helen Garner, and Murray Bail, for instance, publish their books with Text in Melbourne. Gerald Murnane and Brian Castro publish with Sydney-based Giramondo, while Amanda Lohrey has published her last several books with Black Inc.

On the other hand, small publishers have also been very good at identifying new and unique voices. Steven Amsterdam’s first novel, Things We Didn’t See Coming (2009), was published by the (now-defunct) Melbourne small publisher Sleepers Publishing, and went on to win the (also defunct) Age Book of the Year award. More recently, the Melbourne-based literary journal The Lifted Brow has entered into book publishing, and had great success in selling overseas rights to Shaun Prescott’s The Town (2017). It has just published a new work, Axiomatic, by the lauded author Maria Tumarkin.

Small publishers have become so important within Australia that, as I have argued elsewhere, they now publish the majority of Australian fiction and probably have done so for about a decade. Despite their significance, they have not had particularly great success with major awards like the Miles Franklin and Prime Minister’s until quite recently. But these trends appear to be changing.

The chart below shows a strong upward trend for small publishers over the past two years in relation to titles shortlisted for the Miles Franklin. While the historical average since 2000 was only 21% of shortlisted titles coming from small presses, this jumped to 40% in 2016 and 80% in 2017. This is a particularly dramatic spike, and I would be surprised if small presses continued to dominate at this rate, but there are good reasons to believe that the general trend is real.

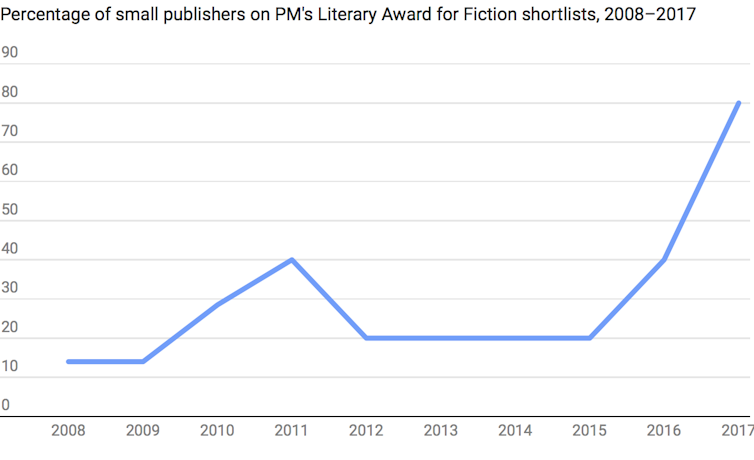

Indeed, the shortlisting data from the Prime Minister’s Literary Award for Fiction shows a nearly identical trajectory to the Miles Franklin data over the last two years, as the chart below illustrates. Like the Miles Franklin, this award saw a jump in shortlisted small press titles in 2016 (40%) and 2017 (80%). In 2017, in fact, both awards shortlisted the same four small press titles: Josephine Wilson’s Extinctions (UWA Publishing), Ryan O’Neill’s Their Brilliant Careers (Black Inc.), Mark O’Flynn’s The Last Days of Ava Langdon (University of Queensland Press), and Phillip Salom’s Waiting (Puncher & Wattmann).

On the one hand, this suggests an enormous shift in the way that the Prime Minister’s award values small publishers; on the other, the unusual — and even bizarre — correlation between the shortlists of the Miles Franklin and the Prime Minister’s awards suggest that this particular instance of small press dominance may be to some degree anomalous. Regardless, the trends are clear, and are also supported by data I have collected on longlisted titles for the latter two awards, which match the trends in the shortlist data.

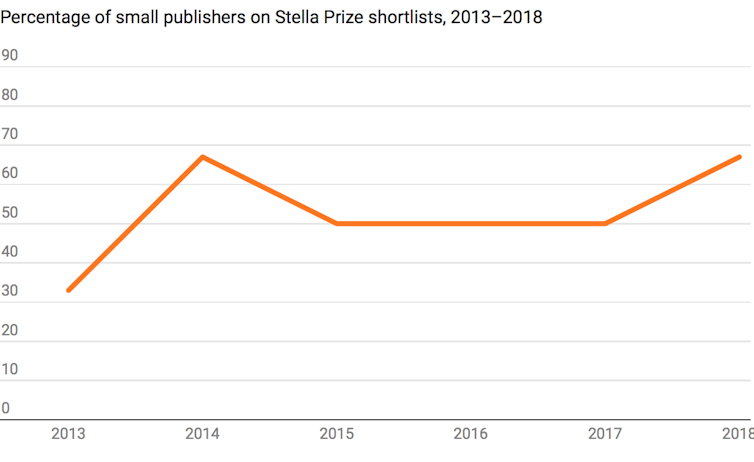

The Stella Prize longlists and shortlists have also recognised small publishers, as you can see in the chart below. Moreover, despite a lower result for small presses in the Stella’s inaugural year (33% in 2013), at least half of its shortlisted titles have been produced by small publishers in every year since.

Small publishers comprise a slim majority of Stella Prize shortlisted titles, with 19 of the 36 shortlisted works (53%) coming from them. Similarly, three of the six winning titles have been produced by small publishers (Text, Giramondo, and Affirm Press). In other words, the Stella Prize has recognised small presses at effectively double the rate of both the Miles Franklin and the Prime Minister’s awards. The dominance of small publishers in the Stella is also replicated in the longlists, with 40 of 72 titles (55%) being produced by small publishers.

There are material reasons why the Stella Prize has probably been more open to small publishers. Co-founder and former executive director Aviva Tuffield is a highly regarded editor, who has worked at small publishers such as Scribe, Affirm, and Black Inc. Current General Manager (and original Prize Manager) Megan Quinlan previously worked at Text Publishing and The Monthly (which has the same ownership as Black Inc.) Many of the Stella Prize judges past and present, such as Tony Birch and Julie Koh, have published their fiction solely through small publishers.

It is also not coincidental that a prize championing women’s writing and gender equity would recognise small publishers. Indeed, these publishers, as Sarah Couper has demonstrated, have a significantly higher proportion of women in executive roles than large publishers do.

I suspect, too, that small publishers are probably more inclusive both in terms of the authors they publish and the kinds of views and perspectives they present. In this sense, the dominance of small publishers’ titles in the Stella is unsurprising given that it is an award that seeks to champion diversity as well as literary quality.

![]() The Stella’s tendency to recognise small publishers has probably influenced the other prizes to do the same. The routine appearance of such works on the Stella lists has normalised the recognition of small press books by prestigious prizes and thus made it more acceptable for other such prizes to do so. While it’s unlikely that small presses will continue to dominate the major prizes at this rate, I nonetheless suspect that they will continue to be taken much more seriously by such awards than they have been in the past.

The Stella’s tendency to recognise small publishers has probably influenced the other prizes to do the same. The routine appearance of such works on the Stella lists has normalised the recognition of small press books by prestigious prizes and thus made it more acceptable for other such prizes to do so. While it’s unlikely that small presses will continue to dominate the major prizes at this rate, I nonetheless suspect that they will continue to be taken much more seriously by such awards than they have been in the past.

Emmett Stinson, Lecturer in Writing and Literature, Deakin University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that takes a look at secret libraries of history.

For more visit:

http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20160819-the-secret-libraries-of-history

Albert Pionke, University of Alabama

In The Man of the Year Million, originally printed in the Pall Mall Gazette on November 6 1893, then-journalist H. G. Wells imagines the descendants of humanity as “enormous brains” with bodies “shrivelled to nothing, a dangling, degraded pendant to their minds”. Wells’ facetious vision of an explicitly cerebral future may be scientifically suspect, but it is accurate with respect to the reputation of pre-eminent 19th-century logician, liberal, and cultural and social critic John Stuart Mill.

Remembered principally by philosophers for his System of Logic and Examination of Sir William Hamilton’s Philosophy, by political scientists for his Principles of Political Economy and Considerations on Representative Government, and by literary scholars for his Autobiography and for On Liberty, Mill’s carefully cultivated image of himself as a mind – exhaustively educated, disinterestedly logical, and meticulously organised – persists nearly 150 years after his death.

And yet, Mill’s humanity ought to count for more than a degraded pendant to his place in intellectual history. An anxiously precocious child, he grew into a complicated, endearing – and sometimes amusing – adult. These less well-remembered features of his prodigious intelligence have recently begun to reemerge from the title pages, endpapers, flyleaves and textual margins of his personal library.

Donated to Oxford University’s Somerville College in 1905, Mill’s book collection from his house in Blackheath has history – including Mill’s personal history – literally inscribed on thousands of its pages. Like many serious readers, Mill read with pen or pencil in hand, marking passages he found interesting, protesting against premises and conclusions he judged facile, and sometimes summarising his own thoughts in annotations on unprinted pages.

Collectively known as marginalia, these unfiltered records of Mill’s original reactions to his books are the subject of an international collaboration between Somerville College and the University of Alabama. The digital component of this effort, Mill Marginalia Online, aspires to digitise all handwritten marginalia in Mill’s library and, in doing so, to reconstruct the sometimes messy process of reading, the initial gut-level reactions, of one of the leading minds of Victorian England.

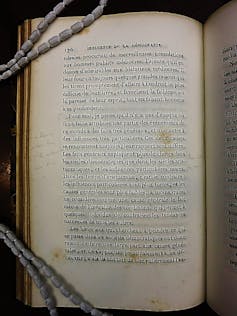

“This is all my eye” – Mill’s expression of scepticism never made it into his overwhelmingly positive review of Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America, Part II. It is, nevertheless, clearly legible on page 170 of volume three as Mill’s first reaction to the French thinker’s somewhat imprecise distinction between what he called democratic and aristocratic centuries.

Mill had, in 1835, introduced England to the first two volumes of Tocqueville’s chef-d’oeuvre, and the men traded friendly and intellectually engaged letters on the subject of democracy over the next five years, as the Frenchman prepared the latter half of his treatise. In recognition of their growing mutual regard, Tocqueville even sent Mill an inscribed copy – it was on the basis of this French edition that Mill penned his second, 1840 review.

And it is in the margins of these same two volumes that Mill recorded comments that might well have tested their friendship. Thus, in response to the aristocratic Frenchman’s thesis, on page 323 of volume three, concerning what we might today call “vocational determinism”, in this case the degrading effects of a life spent “making heads for pins,” Mill wrote “all this mu[st] be taken wi[th] great reserve[ation]. It is not tr[ue] as here state[d]” (I have filled in any missing letters).

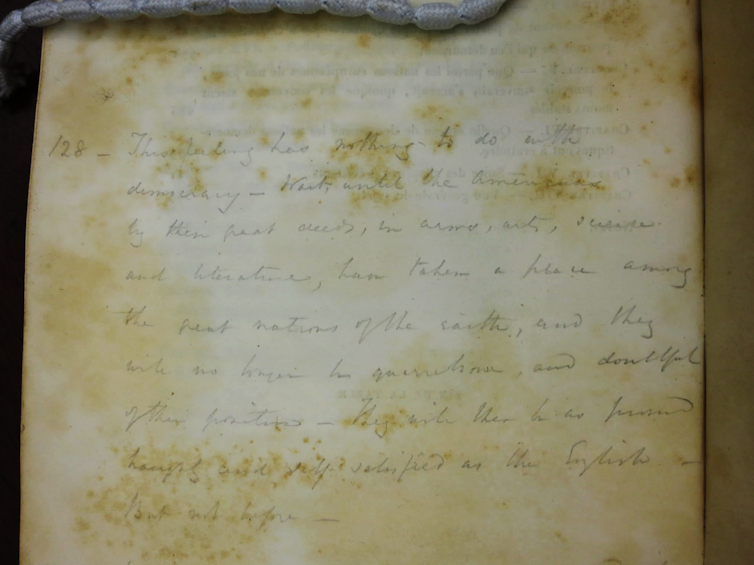

What was true, Mill thought, was Tocqueville’s observation, on page 128 of volume four, that Americans were thin-skinned and quick to take offence in response to criticism. Originally marked with a marginal double score (two vertical lines made in the outer margin of p. 128), this passage received fuller attention in Mill’s annotation on the volume’s back flyleaf:

This feeling has nothing to do with democracy – Wait, until the Americans by their great deeds, in arms, arts, science and literature, have taken a place among the great nations of the earth, and they will no longer be quarrelsome, and doubtful of their position – They will then be as proud haughty and self satisfied as the English – But not before – …

It’s hard to tell whether Tocqueville’s “insatiably vain” Americans or Mill’s “haughty and self-satisfied” British middle classes come off worse in this annotation. Either way, such caustic humour may surprise those accustomed to the measured reasonableness of Mill’s mature publications.

With roughly 10,000 examples of marginalia spread across well over 100 titles, Mill Marginalia Online offers numerous, previously unknown points of entry into Mill’s refreshingly versatile and perennial active mind. In addition to Tocqueville’s Democracy in America, significant works by Francis Bacon, Thomas Carlyle, Auguste Comte, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Maine, Percy Bysshe Shelley, August Schlegel and many others bear revealing marks and annotations in Mill’s distinctive hand.

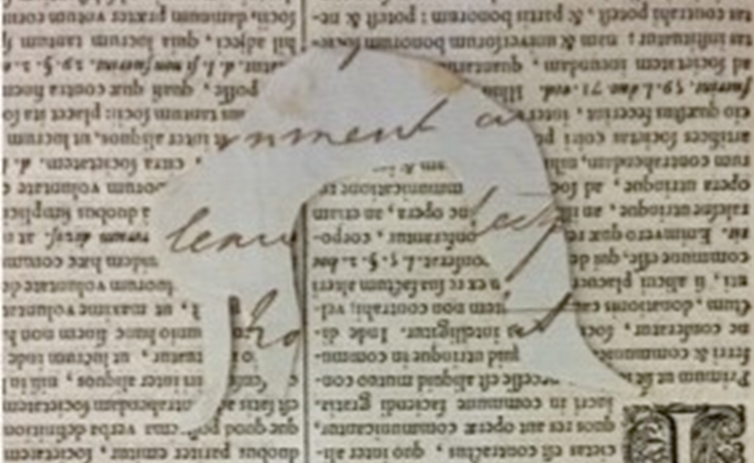

Also hinted at in the Mill collection are aspects of his personality and personal life that may never be fully known. For instance, tucked between pages 674 and 675 of Arnoldus Vinnius’s Institutionum Imperialium – a weighty and much-reprinted history of Justinian law – are two paper dolls, with a third waiting between pages 866 and 867.

Two of these bodies in motion have obviously been commercially produced and then either punched or cut from the pages on which they were printed. The bottom of the two acrobats is even more evidently homemade, although no less painstakingly shaped and coloured. I would guess that their presence in the Vinnius has less to do with the book’s subject matter than with its size and the solidity of its binding – it was an excellent choice for keeping one’s dolls flat and safe.

But the question is, whose dolls were they? Printed in 1665, the book is old enough to have been in the Mill family library when the young John Stuart was tutoring his sisters. Left in the library at Blackheath after his death, it might also have served as a toy depository for Harriet Taylor Mill’s daughter Helen (Mill’s stepdaughter) about whose childhood relationship with Mill we know very little. And need these three objects have had only one owner, or could they have been passed down and around, as playthings sometimes are?

The questions posed by these inclusions assume greater intellectual, as opposed to biographical significance, when we examine the handmade figure more closely. Inverted both back to front and top to bottom, we can see that this doll was crafted from a manuscript – one that bears Mill’s handwriting. The partial word written across the torso could be “government” and that underneath it may be “leaves”. It’s too little for an identification, but more than enough to wonder whether this manuscript was volunteered for doll duty or had been fortuitously scavenged.

What is certain is that these dolls – and every other example of human/book interaction in the roughly 1,700-item personal library of Mill’s – will be catalogued, digitised and rendered fully searchable within Mill Marginalia Online. All of us who work on the project are acutely aware that we cannot know what the research questions of the future might be.

![]() So, rather than limiting our data by type or frequency or what we – today – perceive as its significance, we are striving to record everything that we find, to remove ourselves as much as possible from the results – and to welcome the future by refusing to foreclose upon it.

So, rather than limiting our data by type or frequency or what we – today – perceive as its significance, we are striving to record everything that we find, to remove ourselves as much as possible from the results – and to welcome the future by refusing to foreclose upon it.

Albert Pionke, Professor of English Literature, University of Alabama

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Richard Gunderman, Indiana University

You can tell a lot about our culture by the way we talk about marriage. Take the upcoming exchange of vows between Meghan Markle and Prince Harry. Press coverage will focus on aspects like the cost of the festivities, the size of the crowds and the fashion choices of the wedding party.

But since marriage represents one of the most important factors in predicting a person’s happiness, this marriage – and all marriages – deserve deeper reflection than the press tends to give them.

Marriage is increasingly described as an economic transaction, with marriage rates dictated by the conditions of the “marriage market” – whether matrimony will improve or worsen one’s financial outlook. It increasingly serves as a “status symbol,” a means for couples to signal their rank by sharing photos of expensive engagement rings and extravagant honeymoons on social media. Scholars also suggest that marriage is becoming less of a lifelong commitment, with spouses entering and exiting more freely based on their individual level of satisfaction.

Beyond status, money and personal gratification, none of these trends delineate what a good marriage should actually look like, and what expectations each partner should have.

Fortunately, one of the greatest novels ever published – Tolstoy’s “Anna Karenina,” which I teach regularly to my ethics students at Indiana University – provides deep insights on why some marriages thrive and others don’t.

“Anna Karenina” may have been published 140 years ago, but the doubts and desires of the characters ring true today.

The novel tells the story of four couples.

Dolly is the devoted mother of many children, while her husband, Stiva, cannot believe that he can be expected to devote his life to his family. The novel opens with a marital crisis precipitated by his infidelity.

Anna is a popular and astute socialite married to an honorable yet rather dry senior statesman, Karenin, who is 20 years her senior. Anna discovers that she longs for more.

Anna falls in love with Vronsky, a dashing cavalry officer who grew up in a wealthy but failed family, with no meaningful family life. Anna eventually leaves her husband for Vronsky, which results in her fall from societal grace.

Kitty is a debutante and Dolly’s younger sister, and Levin is a landowner searching for the meaning of life. Though Kitty initially rejects Levin’s overtures, the two later marry and become parents.

The rich human panoply of the novel cannot be boiled down into a few simple rules for a happy marriage. Yet it brims with insights on the differences between happy and unhappy families.

Consider Anna and her brother Stiva. Both see marriage as a contract into which they can enter or leave at will. Stiva cannot understand how a young red-blooded, convivial man such as himself could possibly find contentment by completely devoting himself to his wife, “a worn-out woman no longer young or good-looking, and in no way remarkable or interesting, merely a good mother.”

Surely life owes him more than that, he thinks.

Anna also finds her highly regimented marriage to Karenin less than satisfying and seeks the adventure of romantic love with Vronksy, a man to whom genuine family life is unknown. But ultimately even the lover of her dreams cannot rescue her from her perpetual dissatisfaction.

Levin is one of the characters who most realizes the richness of marriage. In preparing for his wedding, he “had thought his engagement would have nothing about it like others, that the ordinary conditions of engaged couples would spoil his special happiness; but it ended in his doing exactly as other people did, and his happiness being only increased thereby and becoming more and more special, more and more unlike anything that had ever happened.”

Levin is continually surprised by what he discovers of his wife, of parenthood, and of himself as husband and father.

Family life turns out to be far more fulfilling than he ever imagined.

One of the novel’s central insights is this: Marriage is far more than a relationship that merely fulfills the emotional, romantic and material needs of each partner.

In Tolstoy’s view, the best that partners can hope for from marriage is to be shaped by it in ways that make them better human beings. On the other hand, those who enter marriage thinking that it is all about their own satisfaction – supposing that their spouse and union both exist primarily to bring them pleasure – can expect to endure considerable unhappiness.

Anna, for example, thinks she has the right to be adored by all. When others, including her new life partner, Vronsky, seem to take interest in other matters in life, she is overcome by jealousy.

Another damning Tolstoyan criticism of Anna is her willingness to leave the care of her children to wet nurses and governesses. Though she indeed loves them in some sense, she is so preoccupied with her own needs that she has difficulty focusing on the role of a mother for any extended period of time.

While the novel doesn’t promote arranged marriage, it does suggest that a good union is less about picking your one true love from a crowded field of bad prospects than submitting to the requirements – the discipline, even – of loving your family.

A roving eye and a restless heart can always find something to long for elsewhere. But someone who operates from such a perspective will never grow fully into any relationship – precisely because they can always find others to long for. From Tolstoy’s point of view, such lack of dedication represents a form of immaturity.

The mission of being a spouse and parent, Tolstoy would say, is not to satisfy the longings people bring to marriage, but to allow marriage to develop and deepen our desires, enhancing our devotion to what is truly most worth caring about. To flourish in marriage and family life – no less than in life itself – is to learn to love the very things, such as family, to which good people dedicate their lives. In other words, a good marriage makes us better people.

A brief exchange between Stiva and Levin encapsulates this truth beautifully:

“Come, this is life!” said Stiva. “How splendid it is! This is how I should like to live!”

“Why, who prevents you?” said Levin, smiling.

“No, you’re a lucky man! You’ve got everything you like. You like horses – and you have them; dogs – you have them; shooting – you have it; farming – you have it.”

“Perhaps because I rejoice in what I have, and don’t fret for what I haven’t.”

Even though celebrity marriages are twice as likely to end in divorce, many are continually surprised when the marriages of the rich, famous and powerful come to an acrimonious conclusion. They shouldn’t be.

It’s impossible to get inside of the heads of these couples, but I do wonder if they loved their own beautiful lives and their vision of love more than they loved their spouses and their children.

![]() Like Stiva, Vronsky and Anna, did they give their hearts – above all – to what they saw in the mirror?

Like Stiva, Vronsky and Anna, did they give their hearts – above all – to what they saw in the mirror?

Richard Gunderman, Chancellor’s Professor of Medicine, Liberal Arts, and Philanthropy, Indiana University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.