The link below is to an article that takes a look at whether an author’s dying wishes should be observed.

For more visit:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/mar/10/up-in-smoke-should-an-authors-dying-wishes-be-obeyed

The link below is to an article that takes a look at whether an author’s dying wishes should be observed.

For more visit:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/mar/10/up-in-smoke-should-an-authors-dying-wishes-be-obeyed

J. Andrew Deman,, University of Waterloo

Harry Potter is the literary phenomenon of the past century, and while our society has had no difficulty celebrating J.K. Rowling’s work, the literary community has been somewhat slower in figuring out exactly what the series has to say.

We tend to think of Harry Potter as an escapist delight, but Rowling’s work also expertly constructs a poignant extended theme that has more in common with King Lear than most English professors might care to admit. This theme at the core of Rowling’s wizarding world speaks directly to a universal human reality: The struggle to come to terms with our mortality.

Death is obviously big in Harry Potter. Death initiates the core conflict of the series; death escalates in each text; death creates the tool by which Harry can defeat Voldemort; and death resolves the conflict in the end, since Voldemort’s death is the end of the war itself. Death recurs throughout the series, but recurrence is not enough to constitute a theme.

Literary theorist Roger Fowler notes that: “A theme is always a subject, but a subject is not always a theme: a theme is not usually thought of as the occasion of a work of art, but rather a branch of the subject which is indirectly expressed through the recurrence of certain events, images or symbols. We apprehend the theme by inference – it is the rationale of the images and symbols, not their quantity.”

Thus, a theme is a comprehensible viewpoint that emerges from a pattern of recurrence — a statement, if you will, that we perceive through progressive repetition and associated symbolism. Without that statement, a pattern is just a motif. If the author is using that pattern to say something, however, the pattern becomes a theme.

So what role does all this death play in the Harry Potter franchise?

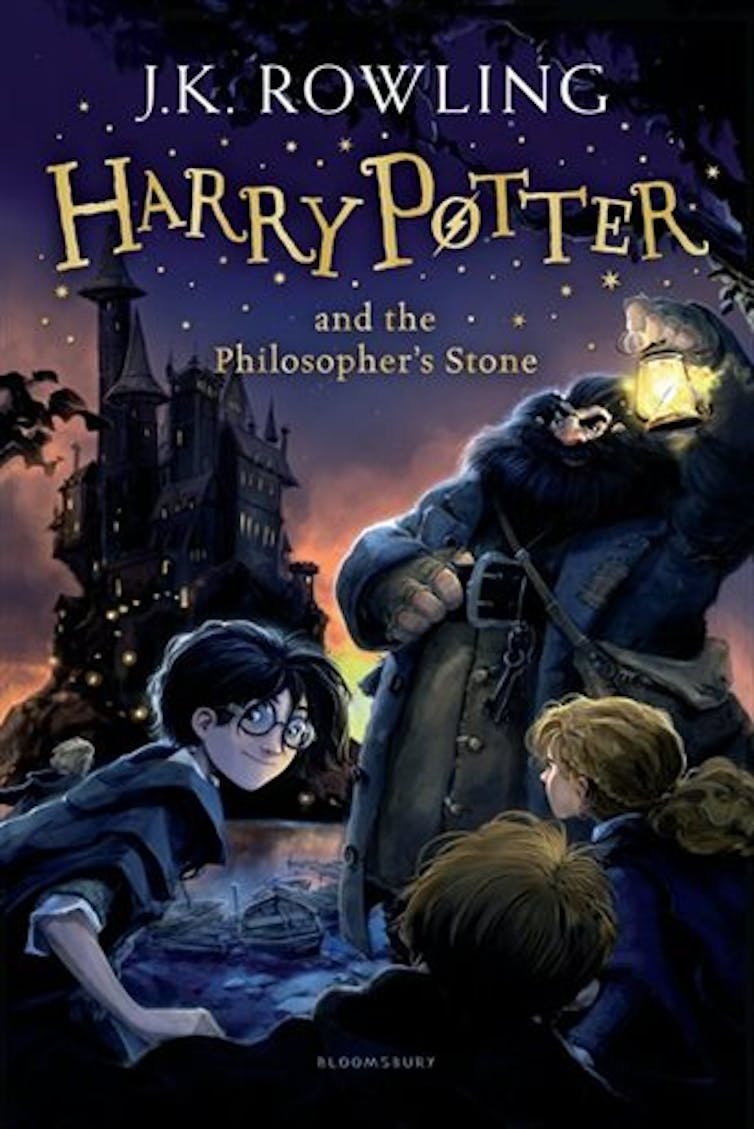

In his first adventure, Harry is tempted by the life-prolonging “philosopher’s stone” of legend.

At the end of that story, Harry is only able to obtain the stone from the Mirror of Erised because he does not want to use it. In this, he immediately establishes his contrast to Voldemort, who desperately seeks the stone in order to extend what the centaur Firenze calls “but a half life, a cursed life.”

Upon hearing this, Harry wonders “If you’re going to be cursed forever, death’s better, isn’t it?” thus showing us Harry’s internal perspective on Voldemort’s choice.

Dumbledore himself confirms Harry’s viewpoint at the end of the novel by telling Harry that “to the well-organized mind, death is but the next great adventure.” If we put these pieces together, the death theme Rowling uses is all laid out within the very first book.

As the series progresses, it is death that defines Harry’s character development. Cedric’s death leaves Harry traumatized. Sirius’s death shows Harry the high cost of Harry’s mistakes and the extent to which death can alter his future. Dumbledore’s death, of course, leaves Harry rudderless and vulnerable, forcing him to mature to a new level of personal responsibility.

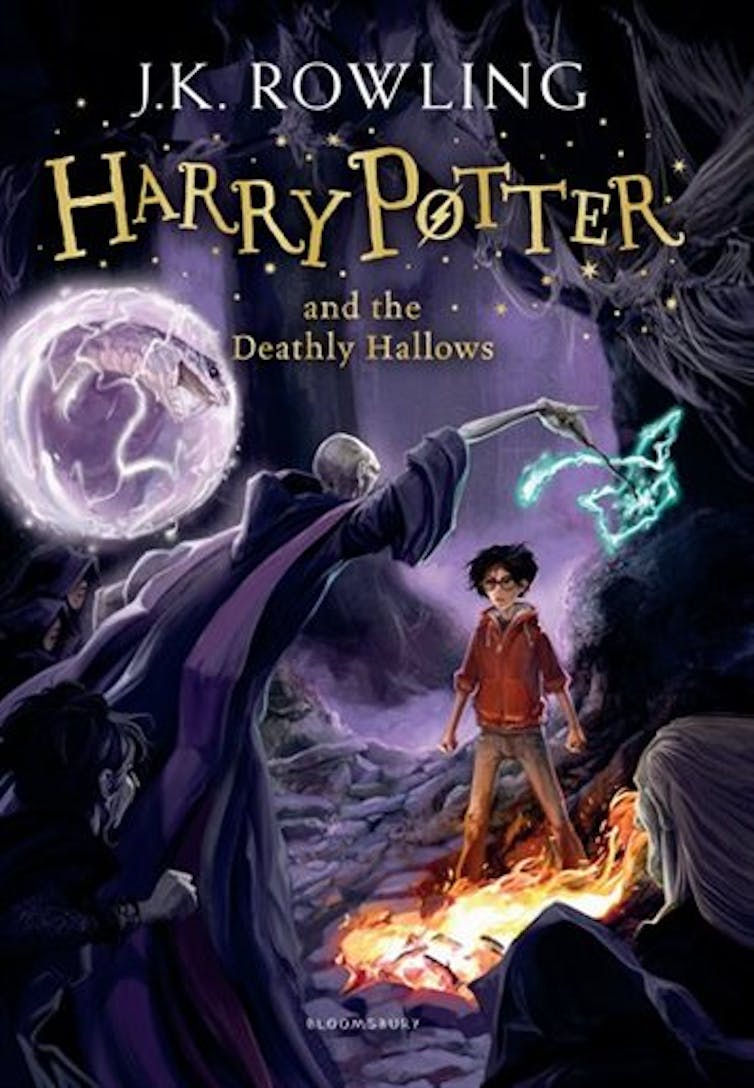

By Book Seven, Harry’s own death represents the ultimate boon that bestows upon him the power to at last defeat Voldemort, whose vulnerability is created by horcruxes, dark magic used to protect him at the expense of his living soul.

As Harry marches to his death, “Every second he breathed, the smell of the grass, the cool air on his face, was so precious.” In this moment, as Harry accepts death, life itself becomes sweet, even beautiful — a sharp contrast to the cursed life that Voldemort cannot escape from.

This contrast is again the pivot-point of the mortality theme that Rowling develops. Voldemort looks like death, he brings death wherever he goes, his army are the “Death-Eaters,” and several aspects of his iconography associate him with the Grim Reaper of legend.

It would be easy to conclude that Harry is simply fighting death in the series, but that role is actually reserved for Voldemort himself, whose name can be translated from the French to mean “flight from death,” not death itself.

The entire series is then the story of an antagonist struggling to deny death, matched against a protagonist who is maturing toward accepting it. If this sounds cynical, Severus Snap agrees with you when he laments that Dumbledore has “been raising him like a pig for slaughter.”

In spite of this objection, Snape is willing to die for the cause of righteousness, just as James and Lilly were, just as Sirius was, just as Dumbledore was, and just as all the casualties of the Battle of Hogwarts were. Even Harry’s poor owl, Hedwig, chooses to die to protect something she loves.

When perceived as a pattern, heroism in Harry Potter means accepting death. In contrast, fighting against death is analogous to raging against the storm for Shakespeare’s King Lear, who, like Voldemort, is reduced to a cursed existence in consequence.

The notion of death in fantasy literature might seem counter-intuitive for a genre that’s commonly associated with escapism. The reality, however, runs contrary, and Rowling’s theme is well within the norms of the genre.

J.R.R. Tolkien, for example, once wrote an essay called “On Faerie Stories,” in which he describes the prominent role of death within the fantasy genre. Tolkien writes that:

“Few lessons are taught more clearly in [fantasy] than the burden of that kind of immortality, or rather endless serial living, to which the ‘fugitive’ would fly. For the fairy-story is specially apt to teach such things, of old and still today.”

For Tolkien, fantasy is a genre that frequently engages with themes of mortality and provides us with “consolation” for our universal fear of death. He refers to his own example, the elves of Middle Earth, to show how he portrays immortality as undesirable.

Tolkien’s elves don’t ever have to die — and their lives are miserable as a result. Though less evil than Voldemort, the nature of their immortal existence is actually quite similar to that of Rowling’s villain — again, a cursed existence.

The strongest encapsulation of the mortality theme in Harry Potter is the story within the story, “The Tale of the Three Brothers,” which is told in the final Harry Potter book. Three brothers face death and respond in three different ways. Only the one who ultimately accepts death is spared a brutal and humiliating end. “And then he greeted Death as an old friend, and went with him gladly, and, equals, they departed this life.”

That “the boy who lived” is also the boy who died is not a paradox. Indeed, Rowling’s argument is that only by accepting our inevitable passing can we truly live a life of meaning and purpose.

![]() To fly from death is to relinquish all the things that make life worth living. This is more than just a clever little message buried in a whimsical boy wizard story —indeed the resonance of this theme within all human beings may in fact be a huge part of the novel’s ubiquitous appeal. Harry Potter, you see, has something to say.

To fly from death is to relinquish all the things that make life worth living. This is more than just a clever little message buried in a whimsical boy wizard story —indeed the resonance of this theme within all human beings may in fact be a huge part of the novel’s ubiquitous appeal. Harry Potter, you see, has something to say.

J. Andrew Deman,, Professor, University of Waterloo

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that takes a look at ten authors who are best known for their posthumous works.

For more visit:

https://lithub.com/10-authors-whose-best-work-was-published-posthumously/

Stacy Gillis, Newcastle University

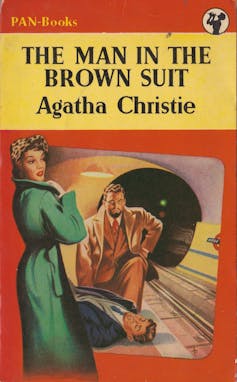

Women’s writing has long been a thorn in the side of the male literary establishment. From fears in the late 18th century that reading novels – particularly written by women – would be emotionally and physically dangerous for women, to the Brontë sisters publishing initially under male pseudonyms, to the dismissal of the genre of romance fiction as beyond the critical pale, there has been a dominant culture which finds the association of women and writing to be dangerous. It has long been something to be controlled, managed and dismissed.

One of the ways that publishers, booksellers and critics use to “manage” literature is through the notion of genre: labelling a book as “detective fiction” becomes an easy way to identify particular tropes in a novel. These genre designations are particularly helpful for publishers and booksellers, with the logic running something like this: a reader can walk into any bookstore, anywhere, and go to the detective fiction section and find a book to read, because s/he has read detective fiction before and enjoyed it.

What complicates this is who makes the decision of which genres are deemed to be appropriate, and which books are put into which category. Genre is also complicated by the idea of women’s writing. Can we have a genre that is designated solely by the sex of the author? What if we turned this around, and rather than a genre, women’s writing was a term we used to simply celebrate writing about women?

Here are five novels by women – and about women – from across the 20th century. These novels all grapple, in very different ways, with women and independence.

Anna Beddingfeld, a self-mocking heroine, who is very aware of the conventions of gender and genre, impulsively buys a ticket to South Africa because the boat fare is the exact amount she has left in the world. She ends up taking down an international crime syndicate with aplomb and panache.

Doss is the expendable unmarried older woman in a Victorian novel. But in this story, she walks out on her largely uninterested family to move into a cabin on an island with a man she has met only briefly. A fantasy of the Canadian wilderness, the novel was one of Montgomery’s few novels for adults.

A rewriting of Jane Eyre, the novel contains all the tropes of the Gothic romance – a castle, a family secret, murder – but these are challenged by one of Stewart’s finest protagonists, Linda Martin. Martin is employed as a governess by an aristocratic family, but rejects the trappings of romance to protect her charge, and her own integrity.

Edana Franklin wakes up in hospital with her arm amputated and the police questioning her husband. It is revealed that she has been travelling back to 1815, where she comes into repeated contact and conflict with Rufus, one of her slave-owning ancestors. A novel that raises important questions about masculinity, power and violence.

One of the earliest pieces of electronic fiction, this retelling of Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) and Baum’s The Patchwork Girl (1913) places the narrative in the hands of the reader, who pieces together the story through illustrations of parts of a female body.

Often popular novels by women have a narrative arc that is visible from the outset: the protagonists will find a romantic partner in the end. In some of the above books, some of the women do, and some of them don’t, find a romantic partner. For those who do, the romance is secondary to the work they do, and the choices that they make about their own lives.

What unites the novels is an exploration of the choices that some women have to make as a result of their sexed and gendered embodiment, whether travelling to South Africa on a whim, being jolted unwillingly back onto a slave plantation, or making an explicit call to the (woman) reader to make choices about how the electronic story develops.

![]() Writing about women (and often by women) gives us some examples of how to challenge the status quo, if only for a little while. Each challenge, however, provides another example of how to effect change in a patriarchal culture. Here’s to the writers about women who have done this – from Jane Austen to Shirley Jackson, from Frances Burney to Josephine Tey, and from Angela Carter to Val McDermid.

Writing about women (and often by women) gives us some examples of how to challenge the status quo, if only for a little while. Each challenge, however, provides another example of how to effect change in a patriarchal culture. Here’s to the writers about women who have done this – from Jane Austen to Shirley Jackson, from Frances Burney to Josephine Tey, and from Angela Carter to Val McDermid.

Stacy Gillis, Lecturer in Modern and Contemporary Literature, Newcastle University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that takes a look at the rise of South Korean authors and thrillers.

For more visit:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/mar/03/the-new-scandi-noir-the-korean-writers-reinventing-the-thriller

The link below is to an article reporting on flood damage to the Australian National University’s Chifley Library in Canberra, Australia.

For more visit:

http://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-03-02/anu-staff-begin-urgent-salvage-job-of-books-at-chifley-library/9500414

The links below are to articles reporting on the longlist for the Man Booker International Prize 2018.

For more visit:-

https://blog.booktopia.com.au/2018/03/13/man-booker-international-prize-2018-longlist/

– https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/mar/12/man-booker-international-prize-longlist-han-kang-laszlo-krasznahorkai

– https://bookriot.com/2018/03/12/longlist-for-2018-man-booker-international-prize-announced/

Bronwen Thomas, Bournemouth University

In the days before social media – and, presumably, media training – Gerald Ratner’s description of some of the products sold in his chain of jewellers as “total crap” became a byword for the corporate gaffe. Recently the chief executive of publisher Hachette Livre, Arnaud Nourry, seems to have suffered his own “Ratner moment” when he described ebooks in an interview with an Indian news site as a “stupid product”.

The interview, which was intended to address the future of digital publishing and specific issues facing the Indian publishing market, was widely misquoted and Nourry’s comments taken out of context. But there is no denying the fact that the publisher criticises his own industry (“We’re not doing very well”) and attacks ebooks for lacking creativity, not enhancing the reading experience in any way and not offering readers a “real” digital experience.

Some commenters on social media welcomed Nourry’s comments for their honesty. They highlight his seeming support for the idea that publishers should be championing writers and artists working to exploit the creative potential of digital formats to provide readers with experiences that may be challenging and disruptive, but also exhilarating and boundary pushing.

//platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

But many of the 1,000-plus commenters reacting to coverage of the story on The Guardian’s website spoke out against “fiddling for the sake of it” – claiming they were not interested in enhanced features or “gamified dancing baloney” borrowed from other media. They also listed the many practical enhancements that ebooks and ereaders do offer. The obvious one is the ability to instantly download books in remote locations where there are no bricks and mortar bookstores. But there are other less obvious enhancements, including being able to instantly access dictionary and encyclopedia entries (at least if you have wifi access) and the option to have the book read to you if you have visual impairments.

Elsewhere, Australian researcher Tully Barnett has shown how users of Kindle ereaders adapt features such as Highlights and Public Notes for social networking, demonstrating that even if ebooks are not that intrinsically innovative or creative, that doesn’t necessarily mean that they can’t be made so by imaginative users.

Nourry clearly isn’t averse to the provocative soundbite – in the same interview he went on to say: “I’m not a good swallower” when asked about mergers and conglomeration in the publishing industry. On the other hand, he also seems very aware of the special place of books and reading in “culture, education, democracy” – so his use of the word “stupid” in this context is particularly inflammatory and insensitive.

My research on digital reading has taught me that debating books vs ereaders is always likely to arouse strong passions and emotions. Merely mentioning the word Kindle has led in some instances to my being shouted at – and readers of “dead tree” books are rightly protective and passionate about the sensory and aesthetic qualities of physical books that the digital version possibly can’t compete with.

But, equally, my research has shown that enhancements in terms of accessibility and mobility offer a lifeline to readers who might not be able to indulge their passion for reading without the digital.

In my latest project, academics from Bournemouth and Brighton universities, in collaboration with Digitales (a participatory media company), worked with readers to produce digital stories based on their reading lives and histories. A recurring theme, especially among older participants, was the scarcity of books in their homes and the fact that literacy and education couldn’t be taken for granted. Our stories also demonstrated how intimately reading is connected with self-worth and helps transform lives disrupted by physical and mental health issues – making comments about any reading as “stupid” particularly damaging and offensive.

I would like to know if Nourry would still call ebooks stupid products after watching Mary Bish’s story: My Life in Books from our project. A lifelong reader who grew up in a home in industrial South Wales with few books, Mary calls her iPad her “best friend” and reflects how before the digital age her reading life would have been cut short by macular degeneration.

![]() As well as demonstrating that fairly basic digital tools can be used to create powerful stories, our project showed that the digital also makes us appreciate anew those features of the physical book we may take for granted, the touch, smell and feel of paper and the special place that a book handed down from generation to generation has in the context of family life.

As well as demonstrating that fairly basic digital tools can be used to create powerful stories, our project showed that the digital also makes us appreciate anew those features of the physical book we may take for granted, the touch, smell and feel of paper and the special place that a book handed down from generation to generation has in the context of family life.

Bronwen Thomas, Professor of English and New Media, Bournemouth University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Laura Scholes, Queensland University of Technology

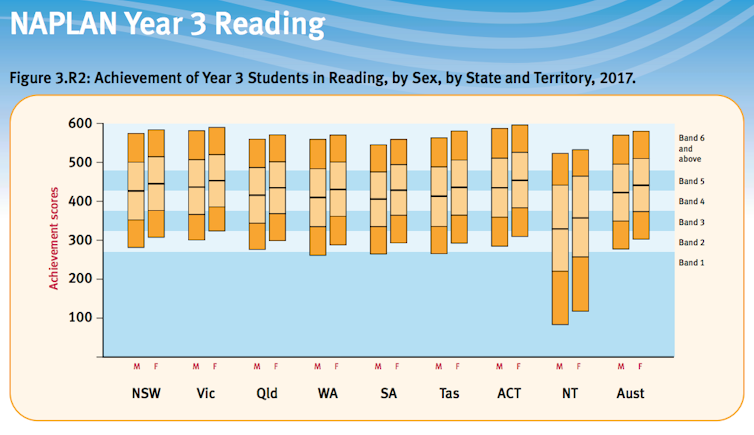

Year 3 reading outcomes of 2017 NAPLAN testing once again demonstrate a gender gap, with boys underachieving compared to girls. A focus on teaching for the test has not closed the gender gap and only reduced student motivation and well-being.

Calls for a review of NAPLAN ten years on are timely. But as well as looking at how high-stakes testing is narrowing the curriculum and causing student stress, we need to consider the testing regime’s influence on boys’ attitudes towards reading.

Read more:

NAPLAN 2017: results have largely flat-lined, and patterns of inequality continue

Reports increasingly highlight how negative attitudes towards reading constrain experiences for some boys. In the United Kingdom, a National Literacy Trust survey of 21,000 children aged eight to 16 found boys were more likely than girls to believe someone who reads is boring and a geek.

This attitude is believed to be related to deep-seated cultural issues that lead many boys to believe reading is feminine and “uncool”. Reluctance to read then translates into less time reading and lower achievement.

There is now a call in the UK for schools to have a policy of promoting enjoyment of reading rather than just a focus on effective teaching of phonics skills.

We have known for a long time that positive attitudes towards reading influence boys’ engagement with reading. Engagement influences practice, resulting in the Matthew Effect as cumulative exposure to print accelerates development of reading processes and knowledge.

Attitudes towards reading are not innate; they are learned predispositions in response to favourable or unfavourable experiences. In this way, a boys’ attitude towards reading develops over time as the result of beliefs about reading and, importantly, specific reading experiences.

In Australia, the focus on NAPLAN has changed the landscape of teaching and literacy experiences for students.

As part of this change, didactic teaching of reading for NAPLAN can compound negative attitudes about the nature of reading at school. Reading is seen as a passive (feminine) endeavour associated with boring schoolwork (preparing for the test).

While teaching phonics is already embedded in good teaching practice, the introduction of the Year 1 phonics check will potentially further narrow the curriculum as teachers are pressured to teach for yet another test. This initiative could also impact on teaching practices for reading in the early years.

Read more:

Explainer: what is phonics and why is it important?

If we are interested in enhancing reading outcomes for underachieving boys, we need to foster positive attitudes towards reading that translate into practice. The change needs to be from a focus on teaching reading to helping boys become successful and satisfied readers.

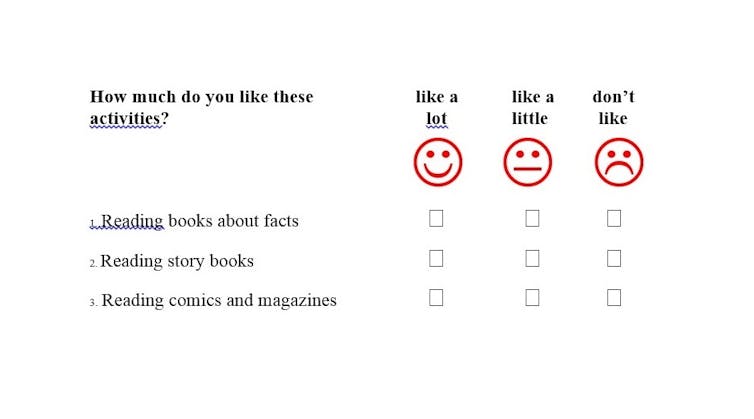

My recent survey of 320 Year 3 children from 14 schools in Queensland identified their self-reported enjoyment of story books, non-fiction books, magazines and comics, and self-reported reading frequency.

Students coloured in a box to reflect an emotive face on a Likert scale to indicate their level of enjoyment and their frequency of reading. Students’ Year 3 NAPLAN reading outcomes were also collected.

Findings from the Pearson test of correlation between survey variables indicated correlation between higher student NAPLAN reading scores and higher levels of enjoyment for reading story books/non-fiction books and higher reading frequency. There was a statistically significant positive correlation between reading scores and reading frequency, and reading scores and reading enjoyment.

Even when teachers are supporting specific learning difficulties (such as dyslexia), it’s important to expand boys’ repertoire of positive reading experiences. This requires a shift from the exclusive teaching of the mechanics of reading to teaching practices that contextualise experiences and encourage enjoyment of reading.

Expand school reading cultures. Directly challenge beliefs about reading being a feminine pursuit. Teachers can select and use texts that challenge what it means to be male and the power structures that exist in school and society.

Focus on the arts. Include artists-in-residence schemes, poetry weeks, dance sessions run by professional dancers, and drama productions that allocate lead roles to disengaged boys. Boys often enjoy working with “readers’ theatre” scripts, which allow them to feel like active participants in a story.

Leave reading choices up to students 50% of the time. Provide a wide range of texts to stimulate interest and build confidence through paired reading schemes and teacher decisions to give students space to talk about and reflect on what was enjoyable.

Promote male mentoring. Include parent-mentors and vertical mentoring with older boys mentoring younger boys in the school.

Let them talk! Boys who are reluctant readers need to have successful reading experiences. Use literature circles with mixed-ability grouping, providing boys with the support they need to focus on the “big ideas” in the story, as well as on the words and structure of the texts.

Include variety. Use interactive classroom activities fit for purpose so that both short, specific focused activities and more sustained, ongoing activities are used, as and when appropriate.

Risk-taking in teacher practice. Bring more creativity and variety. Expose students to new and novel reading experiences.

Implement teaching practices that encourage discussion. Based on Philosophy for Children, enhance reading comprehension as students explore different answers, examine the strengths and weaknesses for each, and critically reflect on assumptions along the way.

Read more:

Research shows the importance of parents reading with children – even after children can read

![]() When the focus is on teaching for the test, direct instruction and an exclusive focus on phonics, there is a narrowing of curriculum and teaching practice. Strategies can be easily implemented in the classroom. We need to move from teaching reading for NAPLAN testing, to teaching boys to enjoy reading to ensure their success.

When the focus is on teaching for the test, direct instruction and an exclusive focus on phonics, there is a narrowing of curriculum and teaching practice. Strategies can be easily implemented in the classroom. We need to move from teaching reading for NAPLAN testing, to teaching boys to enjoy reading to ensure their success.

Laura Scholes, Research Fellow, Australian Research Council (DECRA), School of Early Childhood and Inclusive Education, Queensland University of Technology

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.