Toni Wilkinson

Stephen Chinna, University of Western Australia

Soon after Evgeny Grishkovets and his translator Kyle Wilson walk on stage to perform Farewell to Paper at the Perth Festival, Grishkovets reminds the audience that the performance will be of two hours duration. This advice will be returned to later, when a mild rebuke is delivered to spectators seen glancing at their watches.

While advertised in the festival program as a “one-man show”, the rapport between the actor, Grishkovets, and the translator, Wilson, lends the performance the sense of a double act. Wilson – a translator and specialist in Slavonic languages – has read the script beforehand but in performance he incorporates Grishkovets’s ad libs. Grishkovets almost dances his part as he speaks, pausing for Wilson’s translations, sometimes interjecting.

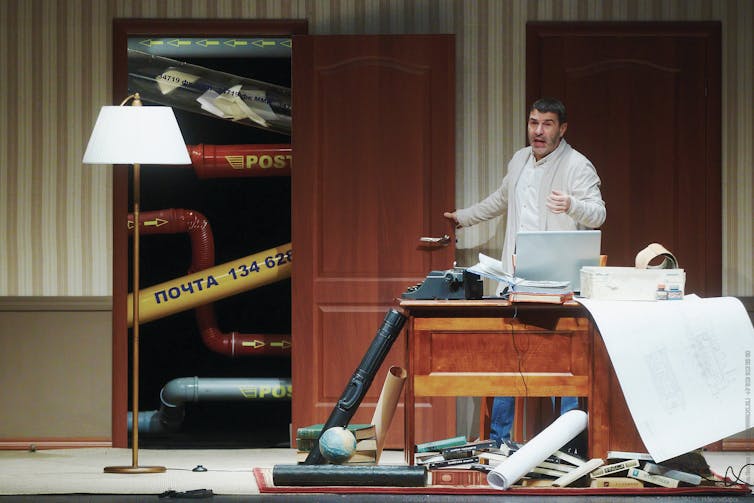

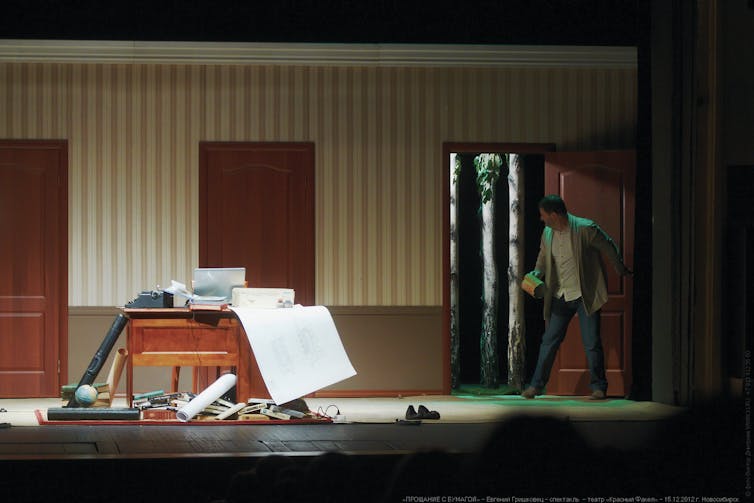

Under fluorescent lights in front of a backdrop of candy stripe wallpaper and five doors, the set is cluttered with the detritus of obsolete objects, such as a writing desk with a set of plans, various papers, and two typewriters. The floor is scattered with books, map cases and a globe of the world. Grishkovets periodically opens one or more of the doors behind him to reveal objects that supply visual reinforcements to his scenarios of loss.

As well as paper, there are farewells to many other things, such as the traditions and the technologies of a previous age. Through the course of the performance, Grishkovets proceeds to offer up a succession of narratives, frequently utilising physical props of material items and practices that have become obsolete. These include things such as quill pens, pen knives, blotting paper, inkwells, the handwritten letter, letter openers, telegrams, and more.

What becomes obvious is that these previous technologies enforced a need to compose, and a time to reflect. He describes the act of writing a letter, the licking and sealing of an envelope, the purchase and placing of a stamp, and the journey to the post office or the mail box. The list of obsolete items and practices continues with typewriters (it would appear that the last one was made in Delhi in 2011), and a nostalgic narration on the joys of owning his first Pentium computer.

Toni Wilkinson, Perth Festival

Many of these items are presented physically through the five doors in the backdrop of the set. For example, a narrative concerning the discovery of two 1000-year old messages written on birch bark leads to Grishkovets opening the doors at either end of the set to reveal birch trees. At suitable moments, other doors are opened to display such objects as a mound of handwritten letters and a bookcase.

In a marvellous display of three sequential door revelations, we see a mailbox in which the young Evgeny posted his first letter while staying with his grandparents. In the second is the mass of pipes and conduits that he imagined transported his letter underground to his parents elsewhere. In the third, the row of dilapidated mailboxes in the stairwell of an apartment building where letters were delivered.

Grishkovets is a subtle performer. His excellent sense of timing, his economy of action, his communication with the audience, all reveal an actor skilled in his craft. Wilson is also an effective performer, recognising the requirements of pace, timing, rhythm and in tune with the subtle nuances of Grishkovets’s delivery of his lines. Wilson’s frequent wry exchanges with Grishkovets over small points of translation add to the flavour of the double act between them.

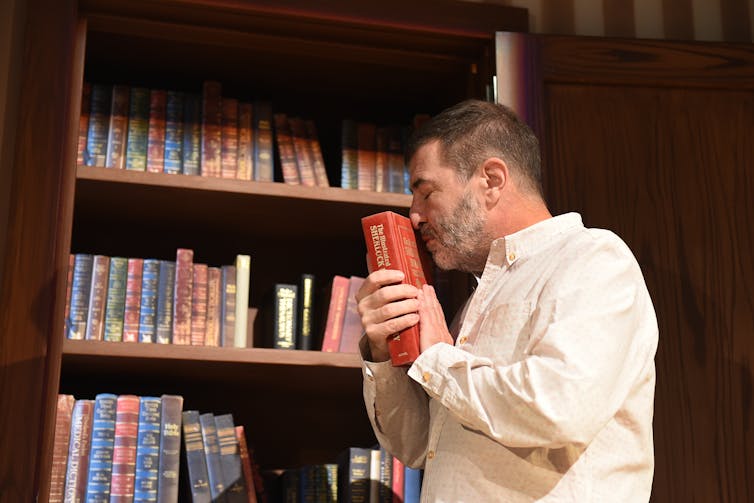

Grishkovets often focuses on the visual, the tactile, the aural and the olfactory aspects of paper technology. Do you appreciate the weight of a book, and the texture of its cover, of its pages? Can you savour the smell of a book – and its dust? Can you enjoy the smell of newsprint, the rustle of a newspaper? Can you savour the smell of an smart phone? Does an iPad rustle?

Toni Wilkinson, Perth Festival

While these juxtapositions have a light tone, the author is invoking a sense of a deeper nostalgia and regret for the “signs of time past, or of times that are passing” as he puts in the program notes.

As well as being a meditation on times past and the fears raised by the dizzying turnover of technologies, there is also a key message here about the importance of patience.

This message is foreshadowed in that early warning concerning the two-hour duration. However, while Grishkovets is lamenting the loss of a slower paced existence and demonising the speed of 21st century life, he does it with humour, a light touch, and a willingness to point out the drawbacks associated with previous technologies and practices in a world of paper.

![]() A thoroughly engaging performance by Grishkovets, aided by the sensitively presented translations by Wilson, was rewarded with strong applause by a full house audience.

A thoroughly engaging performance by Grishkovets, aided by the sensitively presented translations by Wilson, was rewarded with strong applause by a full house audience.

Stephen Chinna, Senior Honorary Research Fellow, University of Western Australia

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.