The link below is to a book review of ‘The Diary of Samuel Pepys,’ by Samuel Pepys.

For more visit:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/nov/06/the-diary-of-samuel-pepys-100-best-nonfiction-books-of-all-time-review-robert-mccrum

The link below is to a book review of ‘The Diary of Samuel Pepys,’ by Samuel Pepys.

For more visit:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/nov/06/the-diary-of-samuel-pepys-100-best-nonfiction-books-of-all-time-review-robert-mccrum

Sarah Keenihan, The Conversation

We’re proud to have five The Conversation authors featured in the The Best Australian Science Writing 2017, edited by Michael Slezak, and with a foreword by Emma Johnston.

The book was launched at The Australian Museum. The blurb says:

Good writing about science can be moving, funny, exhilarating, or poetic, but it will always be honest and rigorous about the research that underlies it.

This is what we’re all about at The Conversation – making sure that all our articles are supported by evidence, and at the same time helping readers see the relevance, the importance, the nuances but also the joy of science and technology.

Our selected authors are good examples.

In Peter Ellerton’s What exactly is the scientific method and why do so many people get it wrong?, he explains there’s a big difference between science and pseudoscience. But if people don’t understand how science works in the first place, it’s very easy for them to fall for the pseudoscience.

In Gender equity can cause sex differences to grow bigger, Rob Brooks writes that moves toward gender equity in opportunity – including the dismantling of patriarchal power structures – might, paradoxically, also widen sex differences.

Robert Fuller’s piece How ancient Aboriginal star maps have shaped Australia’s highway network likens many thousand year old Indigenous travel techniques with modern day GPS tracking. Aboriginal people have long used the stars to help remember routes between distant locations, and these routes are still alive in our highway networks today.

John Long tackles the myth that giant predators might still be cruising around our oceans in Giant monster Megalodon sharks lurking in our oceans: be serious!. Yes, giant sharks did once exist in our oceans – but these went extinct many millions of years ago.

Also included in the book is regular The Conversation author Alice Gorman, with her piece Trace Fossils: The Silence of Ediacara, the Shadow of Uranium, which we republished from Griffith Review State of Hope. The essay won the Bragg UNSW Press Prize for Science Writing 2017, which recognises the best short, non-fiction piece of science writing for a general audience.

These The Conversation pieces are presented in the book alongside 27 other selected science essays published in Australia during 2017, and written by scientists, journalists, philosophers and writers.

![]() Science writer and artist Margaret Wertheim received the UNSW Scientia Medal for Science Communication at the book launch, and prizes for science writing by students in years 7-10 were also awarded.

Science writer and artist Margaret Wertheim received the UNSW Scientia Medal for Science Communication at the book launch, and prizes for science writing by students in years 7-10 were also awarded.

Sarah Keenihan, Section Editor: Science + Technology, The Conversation

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Lauren O’ Hagan, Cardiff University

Open up a book from the late 19th or early 20th century and chances are that you will find an inscription inside the front cover. Often, they are nothing more than handwritten names that state who owned the book, though some are a little more elaborate, with personalised designs used to denote hobbies and interests, tell jokes or even warn against theft of the book.

While seemingly insignificant markers of ownership, book inscriptions offer important material evidence of the various institutions, structures and tastes of Edwardian society, and act as tangible indicators of class and social mobility in early 20th century Britain. They can also reveal vast amounts of information on how both attitudes of ownership and readership varied according to geographical location, gender, age and occupation at this time.

My research involves collecting these inscriptions from secondhand books and working with archives to delve into the human stories behind these ownership marks. I am particularly interested in “everyday” Edwardians – the miner, the servant, the clerk – who are so often forgotten by time, yet played an essential role in ensuring Britain ran smoothly during the war years.

My latest work has focused on the stories of the female heroes of World War I. They weren’t fighting on the battlefield but their contributions at home and abroad were nothing short of incredible. Using the inscription marks they left in books, censuses, local history, and Imperial War Museum archives, I have tracked several untold tales, two of which I’ve written about here.

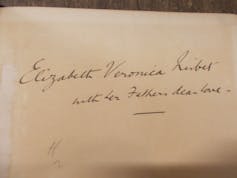

Elizabeth Veronica Nisbet was born in 1886 in Newcastle. The daughter of a colliery secretary, Nisbet was part of the lower-middle class that emerged in Britain at the end of the Victorian era. She studied art at Gateshead College before serving as a nurse with St John Ambulance and the Royal Victoria Infirmary.

In 1913, Nisbet’s father gave her a copy of the biography of cartoonist George Du Maurier, and inscribed it “with dear love”. Du Maurier was well-known for his cartoons in the satirical magazine Punch, which inspired Nisbet’s own artwork. Just one year after receiving the book, World War I broke out and Nisbet headed to France to aid wounded soldiers at St John Ambulance Brigade Hospital in Étaples. This hospital was the largest to serve the British Expeditionary Force in France and treated over 35,000 casualties.

Throughout these troubled times, Nisbet’s passion for art was her salvation: she kept a scrapbook of cartoons, sketches and photos, which provide an insight into wartime Étaples and the vital work of the female nurses. Looking at her artwork, it is clear that she was strongly influenced by the cartoon style of Du Maurier, suggesting that the book remained a treasured artefact to her while she was serving in France.

//platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

Today Nisbet’s work is kept at the Museum of the Order of St John in London. After the war, she returned to Newcastle and worked again as a nurse until the 1920s when she became a full-time artist, travelling regularly to the US and Canada to showcase her work. She died in 1979 at the age of 93.

Born in France in 1876, Gabrielle de Montgeon moved to England in 1901 and lived in Eastington Hall in Upton-on-Severn throughout her adult life. She was the daughter of a count of Normandy and part of the upper class of Edwardian society.

Her affluence is showcased in the privately-commissioned bookplate found inside her copy of the 1901 Print Collector’s Handbook. The use of floral wreaths and decorative banderoles in her plate – both features of the fashionable art nouveau style of the period – mimic the style of many of the prints in her book. This demonstrates the close relationship that Edwardians had between reading and inscribing.

Stepping out of her upper class life, during World War I, de Montgeon served in the all-female Hackett-Lowther Ambulance Unit as an assistant director to Toupie Lowther – the famous British tennis player who had established the unit. The unit consisted of 20 cars and 25-30 women drivers, who operated close to the front lines of battles in Compiegne, France. De Montgeon donated ambulances and was responsible for the deployment of drivers. After the war, she returned to Eastington Hall and led a quiet life, taking up farming, before passing away in 1944, aged 68.

![]() Considering the testing circumstances of war, the survival of these two books (and their inscriptions) is a remarkable feat. While buildings no longer stand, communities have passed on, and grass on the bloody battlefields grows once more, these books keep the memories of Nisbet and de Montgeon alive. They stand as a testimony of the unsettling victory of material objects over the temporality of the people that once owned them and the places in which they formerly dwelled.

Considering the testing circumstances of war, the survival of these two books (and their inscriptions) is a remarkable feat. While buildings no longer stand, communities have passed on, and grass on the bloody battlefields grows once more, these books keep the memories of Nisbet and de Montgeon alive. They stand as a testimony of the unsettling victory of material objects over the temporality of the people that once owned them and the places in which they formerly dwelled.

Lauren O’ Hagan, PhD candidate in Language and Communication, Cardiff University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Verna Kale, Pennsylvania State University

When he published “The Sun Also Rises” in 1926, Ernest Hemingway was well-known among the expatriate literati of Paris and to cosmopolitan literary circles in New York and Chicago. But it was “A Farewell to Arms,” published in October 1929, that made him a celebrity.

With this newfound fame, Hemingway learned, came fan mail. Lots of it. And he wasn’t really sure how to deal with the attention.

At the Hemingway Letters Project, I’ve had the privilege of working with Hemingway’s approximately 6,000 outgoing letters. The latest edition, “The Letters of Ernest Hemingway, Volume 4 (1929-1931)” – edited by Sandra Spanier and Miriam B. Mandel – brings to light 430 annotated letters, 85 percent of which will be published for the first time. They offer a glimpse at how Hemingway handled his growing celebrity, shedding new light on the author’s influences and his relationships with other writers.

The success of “A Farewell to Arms” surprised even Hemingway’s own publisher. Robert W. Trogdon, a Hemingway scholar and member of the Letters Project’s editorial team, traces the author’s relationship with Scribner’s and notes that while it ordered an initial printing of over 31,000 copies – six times as many as the first printing of “The Sun Also Rises” – the publisher still underestimated the demand for the book.

Additional print runs brought the total edition to over 101,000 copies before the year was out – and that was after the devastating 1929 stock market crash.

In response to the many fan letters he received, Hemingway was typically gracious. Sometimes he offered writerly advice, and even went so far as to send – upon request and at his own expense – several of his books to a prisoner at St. Quentin.

At the same time, writing to novelist Hugh Walpole in December 1929, Hemingway lamented the amount of effort – and postage – required to answer all those letters:

“When ‘The Sun Also Rises’ came out there were only letters from a few old ladies who wanted to make a home for me and said my disability would be no drawback and drunks who claimed we had met places. ‘Men Without Women’ brought no letters at all. What are you supposed to do when you really start to get letters?”

Among the fan mail he received was a letter from David Garnett, an English novelist from a literary family with connections to the Bloomsbury Group, a network of writers, artists and intellectuals that included Virginia Woolf.

Though we don’t have Garnett’s letter to Hemingway, Garnett appears to have predicted, rightly, that “A Farewell to Arms” would be more than a fleeting success.

“I hope to god what you say about the book will be true,” Hemingway replies, “though how we are to know whether they last I don’t know – But anyway you were fine to say it would.”

He then goes on to praise Garnett’s 1925 novel, “The Sailor’s Return”:

“…all I did was to go around wishing to god I could have written it. It is still the only book I would like to have written of all the books since our father’s and mother’s times.” (Garnett was seven years older than Hemingway; Hemingway greatly admired the translations of Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy by Constance Garnett, David’s mother.)

Hemingway’s response to Garnett – written the same day as his letter to Walpole – is notable for several reasons.

First, it complicates the popular portrait of Hemingway as an antagonist to other writers.

It’s a reputation that’s not entirely undeserved – after all, one of Hemingway’s earliest publications was a tribute to Joseph Conrad in which Hemingway expressed a desire to run T.S. Eliot through a sausage grinder. “The Torrents of Spring” (1926), his first published novel, was a parody of his own mentors, Sherwood Anderson and Gertrude Stein and “all the rest of the pretensious [sic] faking bastards,” as he put it in a 1925 letter to Ezra Pound.

But in the letter to Garnett we see another side of Hemingway: an avid reader overcome with boyish excitement.

“You have meant very much to me as a writer,” he declares, “and now that you have written me that letter I should feel very fine – But instead all that happens is I don’t believe it.”

The letter also suggests that Garnett has been overlooked as one of Hemingway’s influences.

It’s easy to see why Hemingway liked “The Sailor’s Return” (so well, it appears, that he checked it out from Sylvia Beach’s Shakespeare & Co. lending library and never returned it).

A reviewer for the New York Herald Tribune praised Garnett’s “simple but extremely lucid English” and his “power of making fiction appear to be fact,” qualities that are the hallmark of Hemingway’s own distinctive style. The book also has a certain understated wit – as do “The Sun Also Rises” and “A Farewell to Arms.”

Garnett’s book would have appealed to Hemingway on a personal level as well. Though it’s set entirely in England, the portrait of Africa that exists in the background is the same sort of exotic wilderness that captured the imagination of Hemingway the boy and that Hemingway the young man still longed explore.

But Hemingway’s praise of Garnett leads to other, unsettling questions.

From its frontispiece to its devastating conclusion, Garnett’s book relies on racial stereotypes of an exoticized, infantilized Other. Its main character, an African woman, brought to England by her white husband, is meant to command the reader’s sympathy – indeed, the choice she makes in the end, to send her mixed-race child back to his African family, hearkens to an earlier era of sentimental literature and decries the parochial prejudices of English society.

However, that message is drowned out by the narrator’s assumptions about inherent differences between the races. Garnett’s biographer Sarah Knights suggests that Garnett was “neither susceptible to casual racism nor prone to imperialist arrogance,” yet Garnett’s 1933 introduction to the Cape edition of Hemingway’s “The Torrents of Spring” claims “it is the privilege of civilized town-dwellers to sentimentalize primitive peoples.” In “The Torrents of Spring,” Hemingway mocked the primitivism of Sherwood Anderson (cringe-worthy even by 1925 standards), but as Garnett’s comment indicates, Hemingway imitated Anderson’s reliance on racial stereotypes as much as he criticized it.

What, then, can we glean about Hemingway’s views on race from his exuberant praise of “The Sailor’s Return”? Hemingway had a lifelong fascination with Africa, and his letters show that in 1929 he was already making plans for an African safari. He would take the trip in 1933 and publish his nonfiction memoir, “Green Hills of Africa,” in 1935. The work is experimental and modernistic, but the local people are secondary to Hemingway’s descriptions of “country.”

Late in life, however, Hemingway’s views on Africa would shift, and his second safari, in 1953-4, brought what scholar of American literature and African diaspora studies Nghana tamu Lewis describes as “a crisis of consciousness” that “engendered a new commitment to understanding African peoples’ struggles against oppression as part, rather than in isolation, of changing ecological conditions.”

But back in 1929, when Hemingway was wondering what to do with an ever-growing pile of mail, that trip – along with another world war, a Nobel Prize and the debilitating effects of his strenuous life – were part of an unknowable future.

![]() In “The Letters 1929-1931” we see a younger Hemingway, his social conscience yet to mature, trying to figure out his new role as professional author and celebrity.

In “The Letters 1929-1931” we see a younger Hemingway, his social conscience yet to mature, trying to figure out his new role as professional author and celebrity.

Verna Kale, Associate Editor, The Letters of Ernest Hemingway and Assistant Research Professor of English, Pennsylvania State University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Mike Hutchings/Reuters

Anton Harber, University of the Witwatersrand

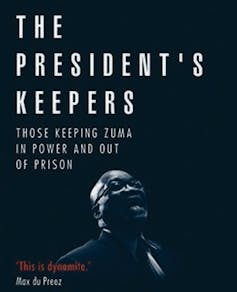

South Africa has produced two must-read thrillers in the past week. They are non-fiction, yet are as gripping and readable as any page-turner.

Veteran investigative journalist Jacques Pauw’s “The President’s Keepers” has, within a week, become a global best seller. It has had the advantage of the best available marketing push by South Africa’s State Security Agency, under the illusion that they were going to stop the book. The State Security Agency sent a cease and desist letter to a defiant Pauw and his publisher, claiming the exposé is in violation of the Intelligence Services Act.

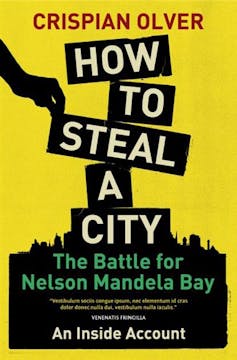

Less well-known, but as important to those who want to understand what is happening in the country, is consultant and activist Crispian Olver’s enticingly-titled “How to Steal a City”.

I recommend you read them together. It will take some courage, as they are a most unsettling combination, but worth it.

Pauw’s book takes you on his journey to uncover the nature of Jacob Zuma’s presidency and its impact on South Africa, a trip that begins in the small Western Cape town of Riebeek-Kasteel and goes, via Moscow, to the Tshwane coffee bars where he meets his sources. Much of what emerges has been reported in bits and pieces elsewhere, but he weaves it together with great storytelling skill, and adds some important new revelations.

It is the most comprehensive picture of the rot at the heart of the Zuma presidency and the toll it has taken on important state institutions. Once he has worked through the tax collector, the South African Revenue Service, the National Prosecuting Authority, and the police, one is left gasping for air at the scale and depth of the destruction.

I don’t think it is necessary to weigh up the accuracy of his much-detailed and well-documented story, except to say that Pauw is a veteran muckraker whose credentials for getting sources to talk, putting his hands on the evidence, weaving all this into readable horror-stories, and withstanding the attacks of those who would stop him, are well established. So much so that the onus is on his detractors to disprove what he is saying. Even if half of it is true, it is chilling.

Olver’s book might be even more important. It’s an insider’s view of how corruption has become the oil that keeps the ruling African National Congress’s political machinery working. Olver was sent in by ANC leaders to help clean up the metropolitan Nelson Mandela Bay region on the country’s east coast and pave the way for local politician and national football boss Danny Jordaan’s 2016 mayoral election campaign. At the same time, Olver was commissioned by then Minister of Finance Pravin Gordhan to clear out the rot in the city structure.

Olver’s story of how he identified and drove out the worst culprits in the city’s corruption, is heartening. He shows that it can be done when you have the political will, and Olver’s toughness. But he also describes how every cent raised to fund Jordaan’s campaign was exchanged for a job or a tender.

The ANC political engine runs on the fuel of transactional politics; without the offerings of jobs and tenders, the machine grinds to a halt. His tale provides rare insight into how the party funding system works as a driver of corruption.

Olver himself starts off as a knight in shining armour, but finds himself increasingly compromised as time passes, until he loses his political backing and flees the region.

Both these writers showed great courage. Pauw left the peace and quiet of running a country restaurant in Riebeek-Kasteel, knowing that this book would bring him the kinds of threats and harassment he experienced in the 1980s when he exposed the dark heart of apartheid’s police hit squads. Olver had to have a bodyguard at his side, so tough was the fight to regain control of the party and city.

Pauw’s book is a triumph of investigative reporting, but also contains a worrying critique of some of its practitioners. Pauw details at least three instances when his fellow reporters have allowed themselves to become part of the partisan mudslinging aimed at driving the good people out of state institutions, and protecting the venal. It is striking that some of the same names come up in all three instances, and all are centred around the local Sunday Times.

![]() While South Africans can celebrate the important role investigative reporters have played in exposing state capture, they should be reminded that some have facilitated it, wittingly or unwittingly.

While South Africans can celebrate the important role investigative reporters have played in exposing state capture, they should be reminded that some have facilitated it, wittingly or unwittingly.

Anton Harber, Caxton Professor of Journalism, University of the Witwatersrand

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Rachel Franks, University of Newcastle

Women have always been central to true crime stories: as victims, perpetrators, readers, and (increasingly) as tellers of these tales. Indeed, these tales, often dismissed as sensationalised violence, offer important opportunities to reflect on crime and crime control.

Many true crime writers today – including numerous women, working in a once male-dominated market – have been biographers, coroners, detectives, historians, journalists, lawyers, and psychologists. These backgrounds bring a style of storytelling that educates us about, not just merely entertains us with, crime. Importantly, many privilege complex and nuanced storytelling over simplistic stereotypes of women as just “bad” or just “good”.

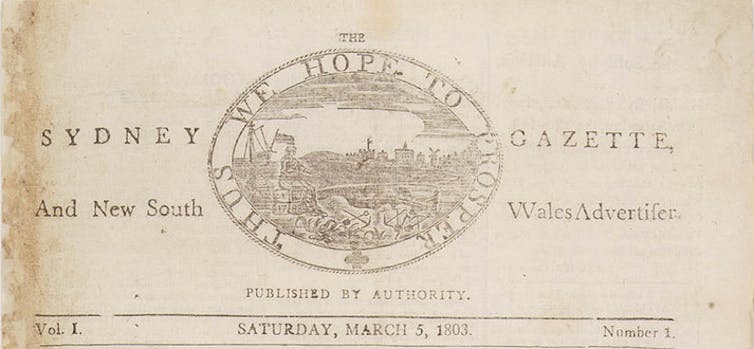

The first Australian true crime stories were transmitted orally, jotted down in journals, and entered into official records. George Howe, editor of our first newspaper, The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, enthusiastically embraced the topic of crime: the paper’s first issue in 1803 included stories of fraud, attempted murder, and the brutal rape of 17-year-old Rose Bean.

The first Australian publication dedicated to true crime is Michael Howe: The Last and the Worst of the Bushrangers of Van Diemen’s Land (1818), by T.E. Wells. This short work is also the story of Howe’s companion, then victim, Mary Cockerill a young Indigenous woman. Cockerill supported Howe in a landscape forbidding and wild to the European settlers. After being betrayed by Howe – he shot her as they were being pursued, facilitating his own escape – Cockerill then used her knowledge of the bush to help authorities. Howe was captured and killed in 1818, bringing his bushranging career to an end.

In the colonial era, a woman’s status as a victim was upheld, or denied, based on her character and her ability to conform to social mores of the time. Today, women are often still judged by what they say and what they wear; their education and their occupation. How many sexual partners have they had? Are they too emotional? Are they not emotional enough? Likewise, some perpetrators have been seen as more heinous because they are women.

In Captain Thunderbolt & His Lady (2011), Carol Baxter skilfully tells the story of Frederick Ward (“Captain Thunderbolt”), a bushranger in the mid-1800s, and his Indigenous partner-in-crime Mary Ann Bugg (“Mrs Thunderbolt”). Bugg – an intelligent, gutsy, trouser-wearing woman – is brought vividly to life, as she breaks the law and defies the feminine expectations of her time.

As Baxter notes, Bugg was dissatisfied with the social status quo, and, like many bushrangers, she received support and sympathy from the wider population. She was not all “bad” but not all “good” either. Indeed, some suggested Mrs Thunderbolt was merely blamed for the deeds of her husband. Bugg outlived her outlaw partner by 35 years, dying in obscurity in Mudgee in 1905.

One of the more dramatic true crime tales of the late colonial period, is the story of Louisa Collins. Caroline Overington looks at the life, and death, of Collins in Last Woman Hanged (2014). Accused of murder, Collins famously endured four trials in 1888, which, as Overington argues, were effectively trials of all Australian women. If women wanted equal rights, including the right to vote, “then, such equality had to be universal: women, too, would hang for murder”. In the first three trials, the juries failed to deliver a verdict. In the fourth trial, the jury found her guilty and Collins was hanged in 1889.

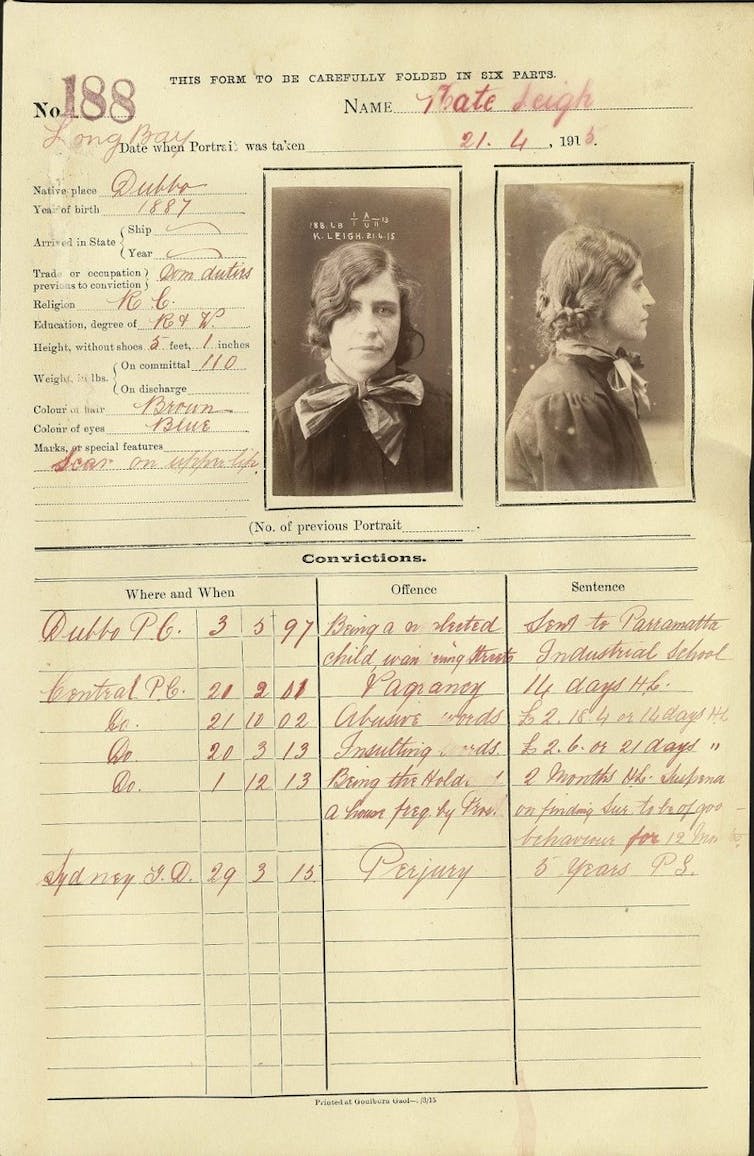

The Worst Woman in Sydney (2016) by Leigh Straw documents the life of Kate Leigh, born Kathleen Beahan, an icon of Sydney’s underworld from the 1920s through to the 1950s. A “famed brothel madam, sly-grog seller and drug dealer”, she is best known for her involvement in the “Razor Wars” when Sydney gangs used razors instead of guns. Leigh could handle a rifle (or any other weapon) and was “an intelligent criminal entrepreneur” who quickly capitalised on opportunities as they emerged. A hardened crook (who was in and out of prison), Leigh was also very generous; her Christmas parties for poor children, in Surry Hills, were legendary for the food and presents given out.

In Nice Girl (2011), Rachael Jane Chin looks at the many dreadful secrets kept by Keli Lane. Found guilty of murder and of lying under oath, Lane’s case is one that is still difficult to believe. Gender, and gendered ideals, stand out within it. Chin unpacks how Lane was a solid, middle-class young woman. She had her boyfriends but was not promiscuous. She was a teacher and had worked hard to become an elite athlete.

But underneath Lane’s “good upbringing and clean-cut appearance”, which earned her the benefit of the doubt from those around her, were five secret pregnancies during the 1990s. Two pregnancies were terminated, two infants were put up for adoption and one baby, Tegan, was murdered. Lane is serving her prison sentence, the crimes she committed as shocking now as when they were discovered. She will be eligible for parole in 2023.

In 1921 the body of 12-year-old schoolgirl Alma Tirtschke was found in an inner-Melbourne alleyway. Colin Campbell Ross was charged with rape and murder, as described in Kevin Morgan’s Gun Alley (2005, updated 2012). We learn the victim, just a child, was quiet but also clever and creative. As readers, we cannot help but speculate who Tirtschke could have grown up to be.

Ross was hanged in 1922: a result of false allegations, a flawed investigation, and a trial held in the press and in the courtroom. He received a posthumous pardon in 2008. This case is particularly important in the history of Australian true crime writing because, as Tom Roberts explains, it highlights the commercialisation of crime, focusing on the headline of the defenceless female, and media-driven moral panics.

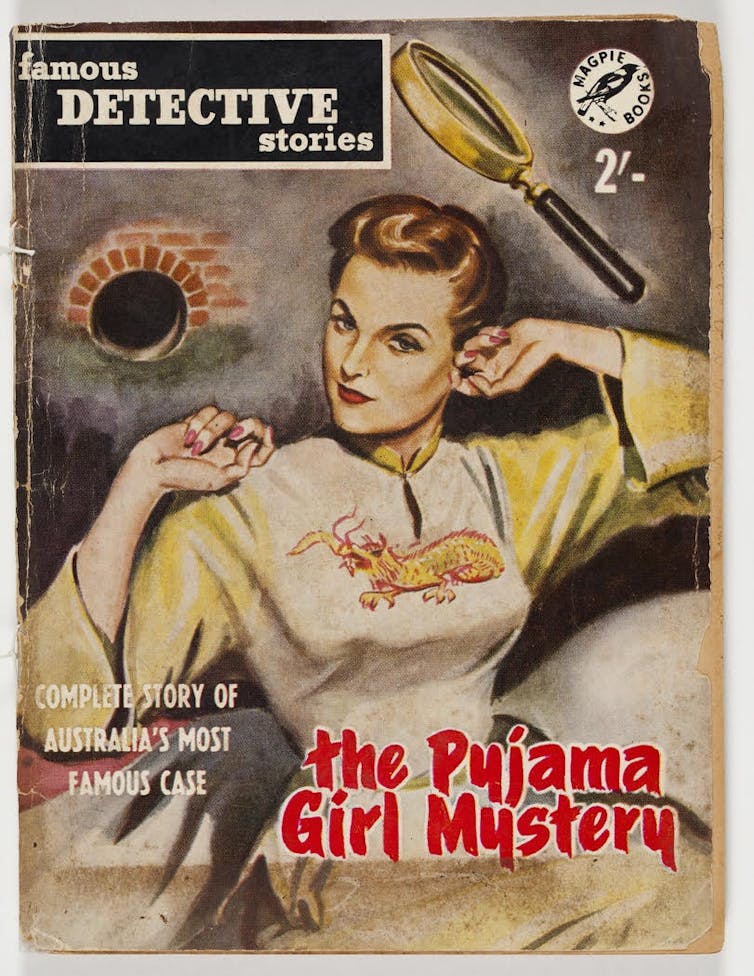

One of Australia’s most famous crimes is the “Pyjama Girl Case”. In 1934 the remains of Linda Agostini, born Florence Platt, was found. She had been shot, beaten, and burnt. Most notably, Agostini was wearing yellow, silk pyjamas, patterned with a dragon: a flamboyant garment in Depression-era Australia. Agostini’s body was placed on public display in an attempt by the police to discover the name of the murdered woman but it took 10 years to identify the victim. In the 1940s and 1950s, Frank Johnson published his Famous Detective Stories series, which included The Pyjama Girl Mystery. Like many of Johnson’s true crime storytelling efforts, the woman at the centre of the criminal case is presented as a sexual object.

The story of Anita Cobby, born Anita Lynch, has been told many times. The first major telling of the brutal rape and murder of the 26-year-old in 1986, is Julia Sheppard’s Someone Else’s Daughter (1991). Sheppard contrasts Cobby and her numerous contributions to the community, as a charity worker as well as a nurse, with the senseless cruelty of the men who took Cobby’s life. Stories like this one, which have stayed in the public imagination over decades, highlight how the impacts of crime extend beyond the victim, family, and friends. They also show how women can be victims of completely random acts of violence.

Many women are victims of domestic violence. The murder of Lisa Harnum, by her fiancé Simon Gittany, is described by Amy Dale in The Fall (2014). Gittany threw Harnum to her death from their apartment balcony, situated on the 15th floor of an inner-Sydney building in 2011. This is a story of control, surveillance, and toxicity. Harnum was trapped in an untenable position: too frightened to leave but also too frightened to stay. When she did try to escape, the result was tragic. Gittany was sentenced to 26 years in prison, with a non-parole period of 18 years.

The once “either/or” binary of “bad/good” women has given way to demands from readers to see women as complex figures within these works. As a result, more and more writers are now increasingly focussed on the human cost of crime.

Kerry Greenwood, known for crime fiction and true crime, has curated two important volumes On Murder (2000) and On Murder II (2002). Rachael Weaver, in The Criminal of the Century (2006), offers a rigorous exploration of colonial serial killer Frederick Deeming. More recently Alecia Simmonds has written on the terrible consequences seen when drug use, violence, masculinity, and psychosis collide in Wildman: The True Story of a Police Killing, Mental Illness and the Law (2015). A dominant force on the landscape of true crime writing is Helen Garner with several compelling works including Joe Cinque’s Consolation (2004) and This House of Grief: The Story of a Murder Trial (2014).

Women are also telling their own stories, as seen in Lindy Chamberlain’s work Through My Eyes (1990). Chamberlain was falsely imprisoned for the murder of her baby daughter, Azaria, at Uluru in 1980. This book delivers a very personal account of one of the greatest miscarriages of justice in Australian history.

![]() Crime is never without context and is never straightforward. Many writers – women and men – know that simplifying these stories with stereotypes, female or male, is just not good enough: for the innocent, for the guilty, or for readers.

Crime is never without context and is never straightforward. Many writers – women and men – know that simplifying these stories with stereotypes, female or male, is just not good enough: for the innocent, for the guilty, or for readers.

Rachel Franks, Conjoint Fellow, School of Humanities and Social Science, University of Newcastle

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Marc Hudson, University of Manchester

Richard Denniss doesn’t mind pissing people off. He’s good at it. His entertaining and punchy book Curing Affluenza will, with luck, kickstart a conversation about mindless consumerism and what we do about it.

Denniss needs little introduction to followers of the Australian policy scene – has been an strategy advisor to Bob Brown, chief of staff of Natasha Stott-Despoja, a former chief executive and now chief economist at The Australia Institute. He’s been sticking his hand in hornets’ nests for a while, whether on climate policy, taxation, the (ab)uses of economic modelling or pretty much anything.

Read more: Enough’s enough: buying more stuff isn’t always the answer to happiness

Denniss co-authored an earlier book with Clive Hamilton called Affluenza, which obviously covered some of the same territory. Affluenza, to cure your suspense, is “that strange desire we feel to spend money we don’t have to buy things we don’t need to impress people we don’t know”.

Ironically enough, there is already a towering pile of published books covering the economic, environmental and psychological costs of consumerism, as well as the pursuit of loneliness, the culture of narcissism, whether the path to happiness is to have or to be, and the collision course our species is on. (I could probably spark joy by decluttering my own shelves of these and other volumes.)

Denniss’ book, which he has been plugging on the radio,

is a bit lighter (in both positive and negative ways) than some of these weighty tomes, striking a tone more akin to the 2007 documentary Story of Stuff.

The book has nine punchy chapters, plus eight additional contributions by thinkers and doers including Kumi Naidoo, Marilyn Waring, Leanne Minshull, and Bill McKibben.

Denniss writes with passion and wit, peppering his argument with memorable metaphors and acerbic questions. The book seeks to show that affluenza is “economically inefficient, the root cause of environmental destruction and that it worsens global inequality”, and to “broaden the menu from which choices can be made – by individuals, communities and countries”.

Denniss distinguishes between consumerism – a love of buying things – and materialism – the love of things themselves. The latter may be beneficial, as long as you care for your things, make sure that they can be repaired, and ensure they are made to last.

He deals well with the “the market won’t stand for it” argument, explaining that “what that really means is ‘rich people who own a lot of shares would react angrily’”. He also perceptively observes that “the process of making things people don’t need and then recycling them into other things they don’t need is now called ‘wealth creation’ or ‘job creation’. More accurate descriptions would be ‘resource destruction’ and ‘waste creation’.”

He’s also good on the relationship between technology and culture, arguing that it’s not that “technology will fix everything, but that technology and culture can and will change everything. The pace and direction of that change, like rope in a tug-of-war, will be determined by the relative strength of forces pulling on it.” But he could have written more on the fact that states are now crucial actors in the innovation game.

And this touches on the book’s biggest weakness: it identifies the problem and asks what is to be done, but largely fails to consider who should do it. Chapters 7 and 8 do contain a series of policy proposals around “banning some or all forms of advertising, banning corporate donations to politicians, preventing former politicians from working as lobbyists”, as well as proposing a ban on new coal mines. But Dennis, curiously, does not propose a universal basic income, which might have some rather interesting effects in getting consumers off the hedonic treadmill.

Read more: The ‘simple life’ manifesto and how it can save us

It’s not always clear who Denniss thinks will get this done, and how they are not going to be fobbed off, demonised, co-opted or demoralised. For my money (actually, I was sent a review copy) I think Denniss underestimates how hard it is for people to take the “voluntary simplicity” route (social status is a powerful driver of consumption), and he could have done more to name and shame companies that are trying to foster psychological insecurity to create consumers for life (covert marketing at children? I mean, seriously?)

Denniss could also have introduced a few more economic concepts (such as positional goods, which decline in value as more people obtain them) and some more case studies, such as the classic example of the Ford Model T, which won the usefulness/cheapness/reliability battle but was defeated by competing car companies that made annual minor cosmetic changes.

You can’t please everyone. The book will doubtless get a kicking from the following groups:

So-called conservatives such as the Minerals Council of Australia, which cops several serves for its lobbying and modelling

Hardcore anti-capitalists (the word capitalism doesn’t appear until page 192, and Denniss somewhat sidesteps the discussion) and economic degrowthers, who think the scale of the problem goes beyond voluntary simplicity

Marxists who will ask who is this “we” in sentences like “we have built a culture where buying things is increasingly unrelated to using things” and wince at the assumption that readers will have “five cashed-up friends”

Social movement strategists who worry that the light green rhetoric will pull focus from more fundamental problems.

![]() But Denniss, I am pretty sure, has not written this book for any of those groups of baked-in enemies, malcontents and despairers. I think he’s written it for Joe and Jane Public, who worry about their kids’ future. And there are enough good metaphors, clear thinking and provocation here to get a good conversation going. So in that sense, mission accomplished.

But Denniss, I am pretty sure, has not written this book for any of those groups of baked-in enemies, malcontents and despairers. I think he’s written it for Joe and Jane Public, who worry about their kids’ future. And there are enough good metaphors, clear thinking and provocation here to get a good conversation going. So in that sense, mission accomplished.

Marc Hudson, PhD Candidate, Sustainable Consumption Institute, University of Manchester

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

This is just a short post by way of an announcement – that I am going to take some time off from my Blogs for the next week or so. I expect to be back posting in the usual manner from about the 16th November. There may be the occasional post before that, but nothing too regular. Why? I just need to get a few things done around the house and in my personal life that I can’t put off any longer, and a short break is also good for my well being. So back in a little bit.

Michelle Smith, Deakin University

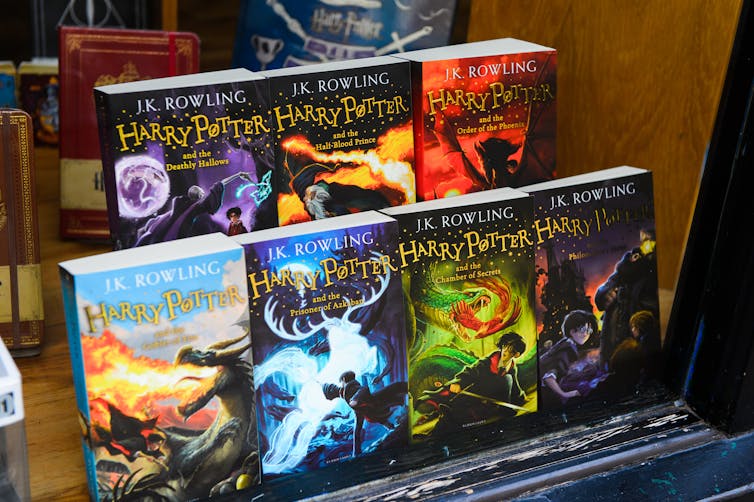

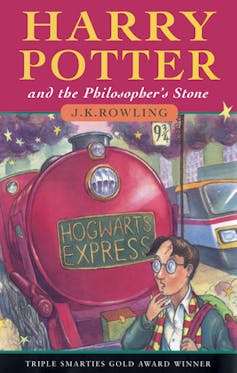

The twentieth anniversary celebrations of the highest-selling book series of all time are now coming to a close. 2017 has been a milestone year for Harry Potter fans in their twenties and thirties, who spent much of their youth in anticipation of the release of each new book or film.

Last week’s Wheeler Centre event Harry Who? The True Heroes of Hogwarts brought together writers, comedians and musicians to celebrate the series. While Harry and his broken glasses predominate at most Potter tourist sites and film screenings, Harry Who? asked the audience to consider who really is the true hero of J.K. Rowling’s stories.

As readers contemplate the long-term legacy of the Potter universe and whether it will endure, it’s also important to consider the overarching messages of Rowling’s series as the most popular example of children’s literature to date.

Harry embodies the key characteristic of some of the most memorable protagonists of classic children’s literature. From centuries-old stories of Cinderella onwards, child and youth characters who are orphans not only foster the reader’s empathy, but are also freed from the expectations and restrictions that biological parents impose.

Melanie A. Kimball explains the twin effects of child orphans in literature:

Orphans are at once pitiable and noble. They are a manifestation of loneliness, but they also represent the possibility for humans to reinvent themselves.

Without the tragedy of Harry’s parents being violently killed by the evil Lord Voldemort, Harry would have had no compulsion to go beyond the “typical” experience of a child with a witch and a wizard for parents.

At Harry Who?, writer Ben Pobjie pointed out that Harry is not exceptional, but that it is his nemesis, Voldemort, who propels Harry to importance. With reference to his dubious celebrity, Pobjie joked that if Voldemort was in Australia, he would “be on Sunrise every morning”. As with the importance of Harry’s lack of parental influence and constraint, the extreme adversity of being Voldemort’s inadvertent nemesis establishes a heroic scenario for Harry to inhabit.

One of the repeated claims throughout the event was that Harry is not much of a hero at all, particularly as he relies on other people to succeed. In the first book of the series especially, Hermione Granger possesses most of the personal attributes and knowledge required to defeat the ever-present threat posed by Voldemort. She is clearly the most intelligent of the Harry, Ron and Hermione trio, and works hard where her male counterparts often attempt to shirk the effort required.

While Hermione’s heroism is important, she clearly plays a supporting role to Harry: the series is, after all, named after him. The emphasis on Harry is reflective of the deep gender bias in children’s literature throughout the past century.

A 2011 study of twentieth-century children’s books found that, on average, in each year, no more than a third of children’s books featured central characters who were adult women or female animals. In contrast, adult men and male animals usually featured in 100 per cent of children’s books.

Though the Harry Potter series does depict some strong and beloved female characters including Professor Minerva McGonagall, it is reflective of an era in which protagonists in children’s literature are usually male unless a book is specifically marketed at a girl readership. In addition, the series is also lacking in the depiction of queer characters, regardless of J.K. Rowling’s post-book declaration that Hogwarts’ headmaster Professor Albus Dumbledore is gay.

With the rapid changes in attitudes toward social and cultural issues including same-sex marriage and children with non-normative gender and sexual identities, the Harry Potter series — as a product of the 1990s and early 2000s – might not endure as well as some might imagine.

Indeed, the issue of changing social norms means that very few children’s “classics” continue to be read by children as decades and even centuries pass. It could be that the series is eventually understood as somewhat outdated and more about producing nostalgia for adults in the same way as the once ubiquitous books of Enid Blyton are viewed today.

One crucial part of the Harry Potter legacy, however, is its effectiveness in encouraging readers, viewers, and now theatre goers with Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, to embrace fantastic stories about young people once again.

Adults in the late 19th and early 20th centuries delighted in children’s stories and made up a significant segment of the audience for plays such as Peter Pan. The dual audience of children’s literature, for both adults and children, was once the norm and one that did not bring any shame or embarrassment with it.

![]() Twenty years on, today’s adults are still gathering to talk about and celebrate the Potter novels they enjoyed as children and have continued to re-read. In addition, other series such as Twilight, The Hunger Games and Riverdale, show the continuing popularity of stories about young people for adults. In 2037 we will be able to tell if the Potter-effect has lasted or if its magic only worked for a brief spell.

Twenty years on, today’s adults are still gathering to talk about and celebrate the Potter novels they enjoyed as children and have continued to re-read. In addition, other series such as Twilight, The Hunger Games and Riverdale, show the continuing popularity of stories about young people for adults. In 2037 we will be able to tell if the Potter-effect has lasted or if its magic only worked for a brief spell.

Michelle Smith, Senior lecturer in Literary Studies, Deakin University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.