BBC

Clare Pettitt, King’s College London

Domestic violence, alcoholism, child abuse, neglect, sexual obsession and torture: Emily Brontë’s 1847 novel Wuthering Heights is nothing if not graphic in its depiction of the messy, frightening and chaotic lives of unhappy families. No wonder critics at the time were repelled by its “shocking pictures of the worst forms of humanity” and its “details of cruelty, inhumanity, and the most diabolical hate and vengeance”. But the women in the novel, trapped in these toxic, inter-generational cycles of abuse, are not passive but remain resolute and resistant.

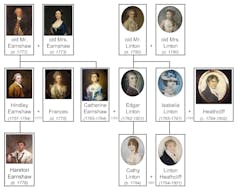

“Whether it is right or advisable to create things like Heathcliff, I do not know,” wrote Charlotte Brontë in her apologetic preface to the 1850 posthumous edition of her sister’s novel. But despite her misgivings, Heathcliff remains one of the most memorable and enduring characters in Victorian literature.

The boy adopted by the Earnshaws as a gypsy child grows up to hang his fiancée’s dog. He refuses a nurse or doctor to his dying son – crying: “Lock him up and leave him.” And he frequently assaults and threatens others – “I’ll crush his ribs in like a rotten hazel-nut” he says of Edgar Linton. Later he also threatens to rip out his wife Isabella fingernails and digs up his great love Catherine Earnshaw’s coffin with necrophiliac fervour.

In Brontë’s description of a fight between Heathcliff and Hindley, Catherine Earnshaw’s elder brother, who has just tried to shoot him, the choreography is cool and exact:

The knife, in springing back, closed into its owner’s wrist. Heathcliff pulled it away by main force, slitting up the flesh as it passed on… His adversary had fallen senseless with excessive pain and the flow of blood that gushed from an artery or a large vein. The ruffian kicked and trampled on him, and dashed his head repeatedly against the flags.“

Violence and abuse

Charlotte Brontë’s preface famously excuses the book as the “rugged” outpouring of her sister’s untutored imagination as a “nursling of the moors” and suggests that Heathcliff is the focus of all the villainy in the book. But Heathcliff is not the only perpetrator of violence and abuse in a novel which bristles with attacks and injuries, both mental and physical.

At one point Hindley orders the servant (and principal narrator) Nelly Dean to: “‘Open your mouth.’ He held the knife in his hand, and pushed its point between my teeth”. In an alcoholic rage Hindley grabs his own baby son and shouts, “‘I’ll break the brat’s neck.’ Poor Hareton was squalling and kicking in his father’s arms with all his might, and redoubled his yells when he carried him up-stairs and lifted him over the banister.” The father then drunkenly drops him, and baby Hareton’s life is only saved because Heathcliff manages to catch him.

Wuthering Heights is, in the words of the novel, “a string of abuse or complainings” – and worse. Brontë trains a singularly cool and unflinching gaze on the violent behaviour that can explode in the intimate spaces of the “home”.

Early critics saw this clearly, but more recent critics have noticed it less. Perhaps the attention given to Brontë as a woman writer by feminist critics in the 1970s and 1980s, hugely important as it was, pushed readings of the novel away from the representation of violence and towards ideas of female repression.

Loathsome women

In her famous 1987 analysis, Desire and Domestic Fiction: A Political History of the Novel, literary scholar Nancy Armstrong reads the double-generation plot as resolved by the middle-class female (Catherine’s daughter Cathy) who disrupts and transforms the old order with her domestic rule. Armstrong says: “Where there had always been brambles at Wuthering Heights, Catherine has Hareton put in her ‘choice of a flower bed in the midst of them’.”

Shutterstock

But such readings perhaps underestimate the manipulative, violent and obsessive behaviour of the female characters and both their complicity and their agency in abuse. Balanced against the “painful appearance of mental tension” in Heathcliff, is what is described by Nelly Dean as the “mental illness” of Catherine.

Catherine pinches Nelly’s arm “spitefully” and slaps her face with “a stinging blow”. She forces Nelly to lie to her husband Edgar and say she is very ill in order to frighten him. Edgar’s sister Isabella scratches Catherine with her “talons” and draws blood. And Heathcliff describes Isabella – his fiancée – as “that pitiful, slavish, mean-minded… abject thing”, despising her for they way she is obsessed with him even though he treats her with appalling cruelty.

“Even the female characters excite something of loathing and much of contempt,” remarked one reviewer at the time. That Brontë dared to make her women loathsome is important. The violence against women in Gothic fiction (as in the novels of genre pioneer Ann Radcliffe) generally sees them depicted as beautiful victims. In other words the females characters suffer beautifully but passively, such as the terror endured by Emily St Aubert in Radcliffe’s Mysteries of Udolpho or the strangulation of the exquisite Elizabeth Lavenza in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

But Brontë’s female characters are not victims. They remain locked in a perpetual struggle both inside the home and with the forces of nature and fate beyond the home. From their girlhoods, when “half savage and hardy” they run free on the moors, neither of the Catherines in Wuthering Heights ever lose their hardiness or give in to any of the men around them. Even Isabella manages to escape her abusive marriage to Heathcliff, and moves away with her baby son. And narrator Nelly Dean is stoic and always protective of her charges, even in the face of simmering violence.

![]() A different feminist argument can be made that Emily Brontë shows us how vital is the tenacious defence of self in a violent world. Catherine, Isabella, Nelly, Cathy: Brontë’s women are fierce and active in their own stories. These women are not passively resilient, but resolute, resistant and strong-willed.

A different feminist argument can be made that Emily Brontë shows us how vital is the tenacious defence of self in a violent world. Catherine, Isabella, Nelly, Cathy: Brontë’s women are fierce and active in their own stories. These women are not passively resilient, but resolute, resistant and strong-willed.

Clare Pettitt, Professor of 19th Century Literature and Culture, King’s College London

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.