Tiffani Angus, Anglia Ruskin University

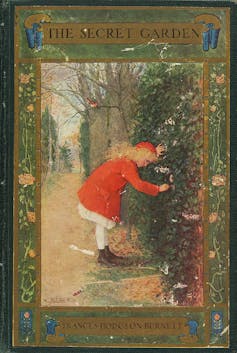

Frances Hodgson Burnett’s 1911 children’s book The Secret Garden has once again been adapted for the screen. Critics have noted that the film about a healing garden has come just at the right time, with The Telegraph calling it “a sparkling COVID antidote”.

Previous filmed versions appeared in 1919, 1949, and 1993. Since those iterations, however, the world has become more tech-enabled and the lives of children more dominated by screens than ever.

Ofcom in the UK estimates that the average three-to-four-year-old spends around three hours a day in front of a screen. This rises to four hours for ages five to seven, 4.5 hours by ages eight to 11, and 6.5 hours for teenagers. Time spent playing outdoors, as a result, is at an all-time low. It might be a wonder then, why, in 2020, a new film about playing outside is being released to an audience that seems so disconnected from it.

2020 has been, to say the least, an odd year. And, after a nationwide lockdown and restrictions currently being reimposed over large parts of the UK, The Secret Garden, a story about the healing qualities of nature – where magic, joy and, importantly, escape can be found – speaks to children (and adults) more than ever. “It sees a group of traumatised people who don’t get out much find solace in gardening and fresh air,” notes Helen O’Hara in Empire speaking about the similarities between the Edwardian cast of characters and our current reality.

Restorative gardens

The story follows Mary Lennox, a self-centred and neglected child, who is forced to move to her uncle’s estate in Yorkshire after her parents die from cholera in India. Left to her own devices and struggling to adjust, Mary finds distraction in exploring the estate’s vast grounds. It is on one of these jaunts that she discovers a hidden garden. Overgrown and mysterious, the place was locked years before by her uncle after his wife died in it.

The garden is, unsurprisingly, irresistible to Mary and, along with her spoiled cousin Colin who believes he’s disabled, and the good-natured Dickon, a kindly maid’s little brother, she finds that it is more than just a place to play. There nature has the power to heal, create relationships and bring joy; the garden also can help mend the wounds of the past, transforming hopeless grief to possibility.

The importance of nature as a source of healing has become increasingly clear during periods of lockdown as we find ourselves longing for green spaces as an escape from the news and our own four walls. Gardens (those of us who have them) and local parks and green spaces become important spaces where children can run around and adults can take a moment to reset. Like in The Secret Garden, we have discovered nature anew and it has restored us.

Time-travelling spaces

In children’s literature, gardens are a place for dreaming, adventures, and even for time travel. In books such as Philippa Pearce’s Tom’s Midnight Garden, Lucy M Boston’s The Children of Green Knowe and Andre Norton’s Lavender-Green Magic, the garden takes children back in time. There they meet people from the garden’s history or other historically important individuals. They have run-ins with their ancestors or undertake actions to save other (usually young) characters from the past who were treated badly or in danger.

The garden is a place to “fix” mistakes and learn about the great mystery and circle of life. Gardens, also, represent time itself: they never stop growing and changing. Every seed planted carries within it the hopes we have for the future.

While The Secret Garden is not a time-travel device as such, it does act as a conduit between the past and present. In it the family’s history is exposed and reckoned with, changing the present and setting them on a course to a new, more hopeful future together.

This connection between gardens and time (and time travel) might appeal to 2020 viewers who are looking for a way to connect the past with an uncertain future. In this story that many adults hold dear, they can rediscover their childhood and escape for a moment in nostalgia for a simpler time.

Once we enter the garden, however, who we are affects how we relate to it. Children have a completely different relationship to gardens than adults: adults see the backbreaking work that goes into them, while children benefit from all that hard work and only see a place to run and play. For the children in The Secret Garden, the garden is a place of discovery, fun, and recovery, in that order. And that is possibly the main key to the story’s longevity: it feeds into a faith in nature as healing, something difficult to ignore amid the friction over climate change and the destruction of some ecosystems.

The past seven months of lockdowns have fostered a hunger for personal green spaces. With the newest film version of The Secret Garden, our love affair with gardens is again brought to the big — and small — screen, where those of us who have been stuck inside can unlock the garden gate and, with a childlike innocence we yearn for, enter a magical green wonderland to take advantage of the healing properties and timeless qualities of a garden that has been waiting for us.![]()

Tiffani Angus, Senior lecturer in Creative Writing and Publishing, Anglia Ruskin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.