Alfonso Martín Jiménez, Universidad de Valladolid

William Shakespeare and Miguel de Cervantes, two of the most important writers of literature, are surrounded by a halo of mystery related to authorship.

In the case of Shakespeare, the question of whether he is the true author of his plays has circulated for some time. In the case of Cervantes, mysteries about authorship tend to concern who wrote the sequel to the first part of Don Quixote, one of the earliest modern novels.

Cervantes published the first part of Don Quixote in 1605. In 1614, an unofficial sequel by the pseudonymous Alonso Fernández de Avellaneda was published. In response, a year later, Cervantes published his sequel to Don Quixote, denouncing Avellaneda’s version in the prologue. Since then, Avellaneda’s identity has become the greatest mystery in Spanish literature.

Cervantes, Shakespeare and education

Both Cervantes and Shakespeare lived and died at around the same time. Shakespeare was born into a wealthy, rural family and Cervantes had humbler origins, yet both had a passion for the theatre and wrote plays.

In both cases, we hardly know anything about their childhoods and education (although it is known that neither went to university).

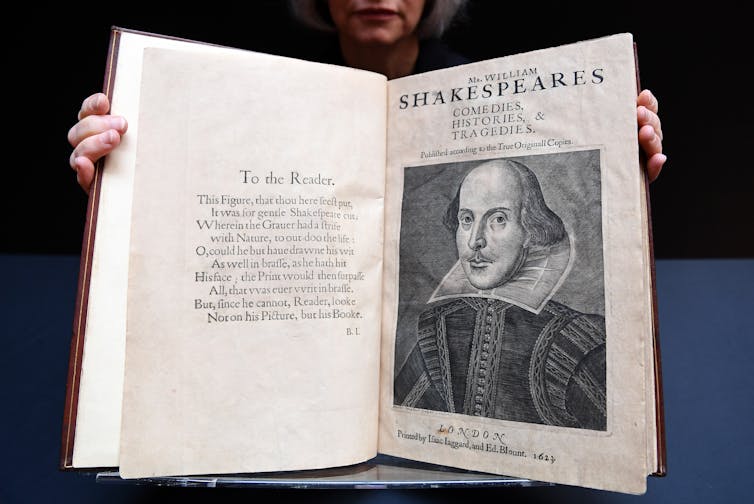

Andy Rain /EPA

Great authors lend themselves to speculation. Shakespeare’s lack of education is one of the main arguments against the idea that he wrote his works, which have been attributed to 80 different authors. While Cervantes’ authorship tends not to be under the same scrutiny, questions about who exactly Alonso Fernández de Avellaneda was, remain.

Cervantes’ own educational background, however, suggests that it is possible to write to a high standard without academic training. If this could be true for the Spanish writer, why not for Shakespeare too?

A very large number of authors have also been proposed as candidates for the authorship of Avellaneda’s sequel to Don Quixote.

Social and cultural prejudices have been important in both cases. Shakespeare’s works show a detailed knowledge of the highest social classes, which is why it is thought that they should have been composed by some illustrious person of the time, such as Sir Francis Bacon.

However, Cervantes also had knowledge of the higher social classes and did not belong to them. Some researchers have even proposed that Avellaneda could have been Lope de Vega, the most prominent Spanish playwright at the time, since it is more attractive to imagine Cervantes confronted with a great author than with a mediocre person.

In both cases, figures who died well before both Shakespeare and Cervantes have been proposed as authors: Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford as the author of Shakespeare’s plays, and the Spanish writer Pedro Liñán de Riaza as Avellaneda, the unconvincing argument being that their works were left incomplete and were finished by other writers.

That said, it’s important to look at other plausible explanations. At the time of the publication of the first part of Don Quixote, there were no copyright laws protecting writers from continuations or plagiarism of works, which explains how Avellaneda’s version came to be.

Similar confusion has been caused in Shakespeare’s case. The Taming of the Shrew had an earlier anonymous version titled: The Taming of a Shrew, seemingly supporting theories that Shakespeare’s version was co-authored, or written by someone else entirely.

These days, however, following a theory put forward by Shakespearean scholar Peter Alexander in 1926, it is generally accepted that The Taming of A Shrew was simply an attempt to record the live production version of the play from memory.

In the case of Cervantes, I think I have cleared the mystery: we already know what Cervantes thought about Avellaneda’s identity, which should put an end to absurd speculation.

Cervantes and issues of authorship

As one popular theory goes, Avellaneda’s sequel to Don Quixote should be read as an embittered response to Cervantes’ parody of two real people: Lope de Vega and Jerónimo de Pasamonte. Pasamonte was a soldier from the region of Aragon who took part – as did Cervantes – in the battle of Lepanto (1571). Cervantes is said to have behaved heroically in the battle since, despite being ill, he insisted on fighting and was wounded several times.

Amani A/Shutterstock

Shortly afterwards, in 1574, Pasamonte was taken prisoner and spent 18 years in captivity. Upon his release, he returned to Spain and finished his autobiography, Life and Works.

When writing about the capture in 1573 of La Goleta (where there was in fact no actual battle), Pasamonte claimed to have acted as heroically as Cervantes at the battle of Lepanto.

After seeing how Pasamonte had usurped his heroic deeds in his autobiography, Cervantes satirised it in the first part of Don Quixote. Cervantes turned Jerónimo de Pasamonte into Ginés de Pasamonte, a galley slave, who is presented as a liar, a cheat, a coward and a thief, and is gravely insulted by characters Don Quixote and Sancho Panza.

The revenge of Pasamonte

The hypothesis that Pasamonte was Avellaneda, proposed by Martín de Riquer, an academic at the Royal Spanish Academy of the Language, is increasingly accepted.

As I have probed in my book, “The two second parts of Don Quixote”, Pasamonte sought to take revenge on Cervantes, writing a sequel to Don Quixote with the intention of robbing Cervantes of his earnings from the second part. In order not to be linked to Cervantes’ galley slave, he then signed it under a pseudonym.

To get revenge on Avellaneda, Cervantes imitated his imitator and created a masterly scene, making the literary representation of Avellaneda (personified in a character known as Jerónimo) recognise his Don Quixote as the true one.

As attractive as speculation about Shakespeare and Cervantes’ authorship may be, looking closer at their lives shows just how irrelevant class, education and conspiracy theories are in terms of explaining their genius.![]()

Alfonso Martín Jiménez, Catedrático de Teoría de la Literatura y Literatura Comparada, Universidad de Valladolid

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.