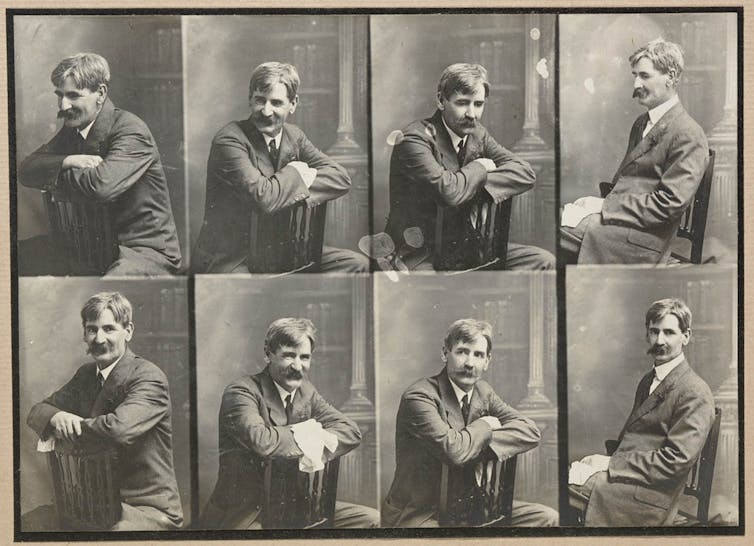

Wikimedia Commons

Dave Drayton, University of Technology Sydney

Why do we tell stories, and how are they crafted? In this series, we unpick the work of the writer on both page and screen.

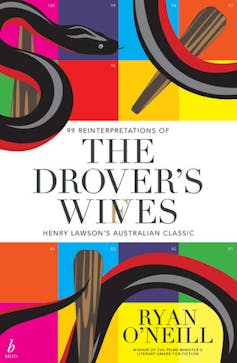

Ryan O’Neill’s recent book The Drover’s Wives joins a rich corpus of Australian literary works inspired by Henry Lawson’s short story, The Drover’s Wife (first published in The Bulletin in 1892).

But O’Neill’s approach differs from that of other authors, by offering not one reinterpretation – as in Frank Moorhouse’s satirical take and Barbara Jefferis’ feminist retelling, for example – but 99 different versions of the story.

His book envisages the Lawson story in various forms, including: as a tweet, a school English essay, an Amazon book review, a limerick, a computer game, a gossip column, and even a sporting commentary.

O’Neill’s book is dedicated to both Henry Lawson and French novelist Raymond Queneau. The latter was a founding member of the Oulipo (Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle), a mostly French assortment of experimental writers, mathematicians and scientists, founded in 1960.

O’Neill attempts Queneau’s method of literary variations on a theme in Exercises In Style (first published in French in 1947), but with an Australian context.

Goodreads

Lawson’s The Drover’s Wife provides the central narrative of O’Neill’s test. In the story, the titular wife of the absent drover spends a sleepless night keeping watch for a snake that had earlier alarmed her children. She passes the time reminiscing on hardships she has faced in the bush before. As daylight nears, the snake appears, and she clubs it to death.

As with Exercises In Style, the original narrative in O’Neill’s book is of secondary importance to the telling and the myriad ways these tellings transform the tale.

O’Neill’s experiment highlights the fact all writing is constrained by certain rules. It’s easier to play the game when you know these rules (and bend them, too).

By taking a text so familiar as its starting point, O’Neill’s tweaks show the conventions of 99 different forms of writing, while shining new light on Lawson’s classic in the process.

Narrative techniques

The fourth reinterpretation in The Drover’s Wives – a “Year 8 English Essay” – begins with the prompt: “What narrative techniques does Lawson use to shape the reader’s perception of the drover’s wife?” With some substitution, we might re-render the question: “What narrative techniques does O’Neill use to shape the reader’s perception of The Drover’s Wife?” Let me count the ways …

Among the most interesting rewrites is a version of the poem where the story is reduced to only onomatopoeia (words that look like the sound they make): the snake is represented by “slithers, sizzles and snaps”.

In another version, he experiments with “spoonerisms” – a display of shining wit where the initial syllables of two or more words are transposed. Instead of a “small herd of grass eaters”, O’Neill renders the drover’s flock as a “small herd of ass greeters”.

He even includes a tanka, a Japanese poetic form similar to haiku:

A snake approaches.

The woman and children run

And hide in the house.

Through the long night she watches –

Shedding memories like scales

And the snake burns with the dawn.

O’Neill departs from the methods originally proposed by Queneau’s book by progressing into more contemporary territory (using PowerPoint lecture slides; a 1980s computer game; emojis; tweets; an Amazon book review; a reality TV show; a meme; a spam e-mail; and internet comments).

He also uses forms specific to an Australian cultural context (an RSCPA report; a letter to the Daily Telegraph; Ocker; and Bush Ballad).

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

Techniques of transformation

A useful way to illustrate the impact of each technique employed by O’Neill is to examine its effect on the opening paragraph in Lawson’s original, used to establish the scene:

The two-roomed house is built of round timber, slabs, and stringy-bark, and floored with slit slabs. A big bark kitchen standing at one end is larger than the house itself, veranda included.

In O’Neill’s text:

-

the Monosyllabic chapter re-renders the opening with single syllable words: “They lived in the bush in a shack with two rooms, miles and miles from the main road […] ”

-

the Yoked Sentence chapter, requiring each sentence to begin with the last word of the previous sentence, opens: “The drover’s wife and her four children lived in an isolated house deep in the bush. Bush was all around, and the nearest neighbour was miles away. Away to the north somewhere, the drover […]”

-

in the Lipogram chapter, which requires the conscious omission of one or more letters, the omission of the letter E renders the exposition differently: “A bush cabin in an outlying part of Australia marks a distant location for our story”.

The opening paragraph is likewise transformed by the use of rhyme in various other chapters.

One that takes the form of a 1950s Children’s Book begins: “There was once a bush farm that the sun rose over, and on that little farm lived the wife of a drover.”

In the Elizabethan Drama chapter, the chorus does the expositional work, beginning their prologue: “A household, poor but rich in dignity / In fair Australia where we lay our scene / Bush all around in stretches to infinity / No indoor plumbing, just an old latrine.”

As is common, the opening lines of the limerick chapter introduce not the house, but the central character of the poem: “There once was the wife of a drover, Who met with a snake, and moreover …”.

In the 1980s Computer Game chapter, the new level of interactivity is made apparent with a shift to second person narration: “You are in a large kitchen by a two-room house”.

A similar technique is used to achieve the tone in the Cosmo Quiz chapter, which parodies the conventions of a glossy magazine quiz: ten multiple choice questions to show you whether you’re a time traveller’s wife, a Stepford wife or a drover’s wife.

How do these various narrative techniques shape perception of Lawson’s original story? On their own, each may heighten or enhance a latent quality that lies in waiting. For instance, the Cosmo Quiz reveals the gender dynamics, satirising the protagonist’s apparent absent agency.

Taken as a whole, the book functions equally as a playful and experimental collection of brief narratives, and an illustrative compendium of writing techniques.![]()

Dave Drayton, Lecturer in Creative Writing, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.