IMDB

Sascha Morrell, Monash University

The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1925 masterpiece of the Jazz Age, ushers readers into a corrupt but glittering world of cocktails, fast cars, stolen kisses and broken dreams. Status anxiety and conspicuous consumption generate a dazzling, often surreal poetry as the novel unfolds over a single summer in Long Island, New York. Beneath them trembles an ominous sense of malaise.

The novel is narrated in the first-person by Nick Carraway, a well-to-do Yale graduate from the Midwest, whose limited acquaintance with the millionaire Jay Gatsby is the reader’s only window onto the mysterious title character.

Fitzgerald’s editor Max Perkins complained to the author that Gatsby’s characterisation was too vague — that readers “can never quite focus upon him” — but this criticism missed the point. Jay Gatsby is not a man but “an unbroken series of successful gestures”, the product of an age — not unlike today’s culture of Instagrammable celebrity — in which identity is less a matter of innate qualities than of projecting an image.

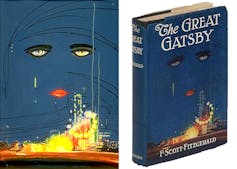

Fittingly, the only God invoked in Gatsby appears on a billboard, in the famous image of oculist Dr J.T. Eckleberg’s gigantic blue eyes looking down on events in admonition.

ResearchGate, CC BY

The Great American novel

Although short in length, The Great Gatsby is widely recognised as an exemplar of that most elusive of literary phenomena: the Great American Novel. It achieves aesthetic greatness as a self-conscious tour de force, the product of Fitzgerald’s desire “to write something new – something extraordinary and beautiful and simple [and] intricately patterned” as he wrote in a 1922 letter to Perkins.

Its American-ness is likewise self-conscious: one of Fitzgerald’s working titles was Under the Red, White, and Blue, and Nick’s account of Gatsby’s rise and fall exposes deep flaws and fissures underlying the American Dream of unlimited social mobility.

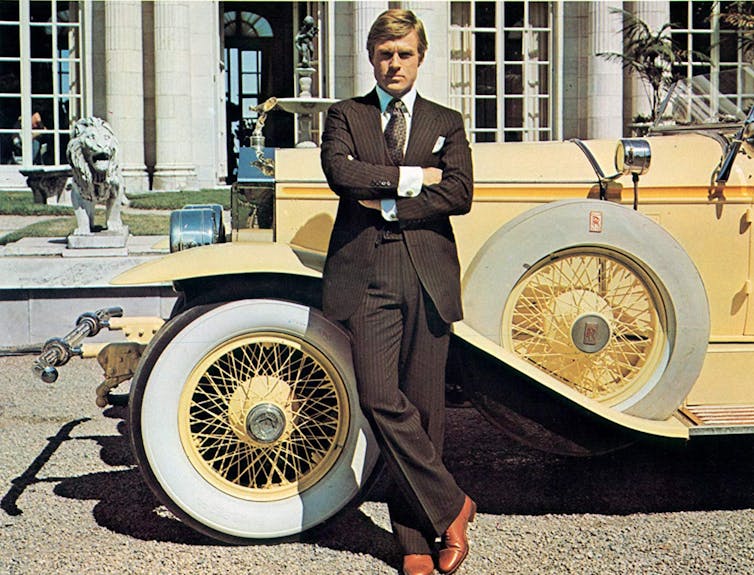

IMDB/Warner Bros. Pictures

Affirming the presence of class prejudice in the land where all men were supposedly created equal, Gatsby constructs a fragile romance across the gulf between old and new money — a gulf that separates Gatsby from his love interest Daisy and her husband Tom Buchanan. Whereas Daisy and Tom come from established families, Gatsby lacks pedigree. The sources of his vast wealth are the subject of much speculation as his colossal mansion dwarfs those of other millionaires with freshly-minted fortunes.

Erosion of orthodoxies

Like many of his modernist contemporaries, Fitzgerald was fascinated by the erosion of old orthodoxies and traditional constraints in the aftermath of the first world war. For women, many taboos on dress and deportment were lifting, and Gatsby’s female characters play sports, dance wildly, and drink and smoke to excess — even in the midst of Prohibition. Yet for all its “spectroscopic gaiety”, such license brings little fulfilment.

IMDB/Paramount

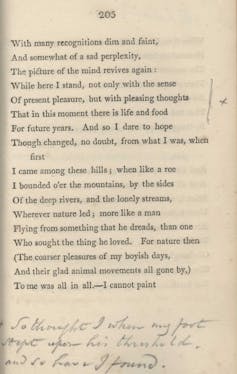

In Chapter 1, the jaded Daisy expresses a sense of crippling ennui: “I think everything’s terrible anyhow […] And I KNOW. I’ve been everywhere and seen everything and done everything […] God, I’m sophisticated!”

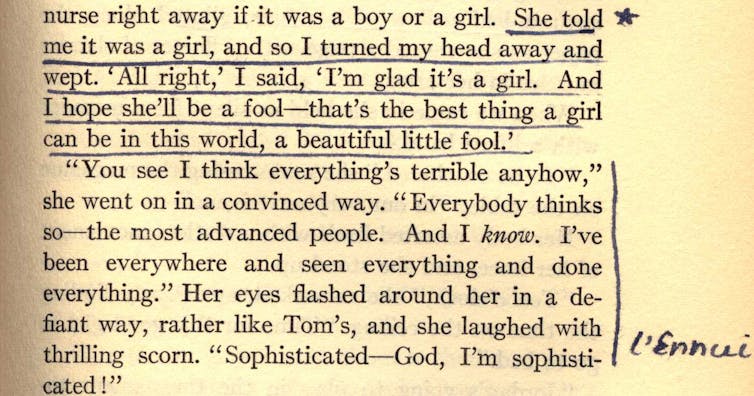

Those with the right connections can afford to be amoral. When Daisy accidentally runs down Myrtle and flees the scene in Gatsby’s “monstrous” car, Tom manages a cover-up, shifting the blame onto Gatsby. As Nick reflects:

They were careless people, Tom and Daisy — they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness […] and let other people clean up the mess they had made.

Social mobility and the question of race

In the year of Gatsby’s publication, US President Calvin Coolidge announced “the chief business of the American people is business”, and in Fitzgerald’s novel it seems that “the pursuit of happiness” — that vague third term in the Declaration of Independence — has been reduced to the pursuit of material success.

IMDB

Even romance and tragedy obey the logic of boom and bust. Nick reports in stockbroking language that Gatsby’s failure “temporarily closed out my interest in the abortive sorrows and short-winded elations of men”, and Gatsby’s love for Daisy — a golden girl whose voice is “full of money” — is as deeply rooted in class and material aspirations as in sexual or personal attachment.

He desires not only Daisy but what winning her would symbolise. Indeed when the penniless Gatsby first met her, Daisy’s social elevation as a Kentucky debutante is said to have “increased her value in his eyes”.

Gatsby’s publication coincided with a high water mark of racism and xenophobia in the United States. The Johnson-Reed Immigration Act of 1924 introduced strict immigration quotas, while the revitalised Klu Klux Klan peaked at four million members in the same year. The novel has drawn criticism for its marginalisation of African Americans: one would hardly know from Fitzgerald’s novel that the Harlem Renaissance was underway. Fitzgerald is credited with naming the Jazz Age, but largely erases its origins.

Gatsby does lampoon racial bigotry through Tom Buchanan, who spouts “impassioned gibberish” about “the white race” being submerged. Fitzgerald alludes here to two influential eugenicist studies of the period, Madison Grant’s The Passing of the Great Race (1916) and Lothrop Stoddard’s The Rising Tide of Color (1920).

Nick calls Tom a “prig”, but he too associates race with class difference when the spectacle of “three modish negroes” driven by a “white chauffeur” prompts his reflection that this is a world where “anything can happen … even Gatsby”.

Sensuous prose

Fitzgerald’s prose is never more richly sensuous than when dealing with the strange alchemy of affluence, and the film adaptations by Jack Clayton (1974) and Baz Luhrmann (2013) struggle to do justice to Fitzgerald’s verbal pyrotechnics.

How can one portray “a scarcely human orchid of a woman” sitting in “ghostly celebrity” under a white plum tree, as a Hollywood actress is described? Like the cover of the novel’s first edition, Gatsby’s halls are “gaudy with primary colors”. His parties swell to “yellow cocktail music”, while a “green light” shines from Daisy’s dock across the bay.

USC

In the novel’s closing paragraphs, Gatsby’s faith in this green light symbolises the vagueness of an American commitment to an endlessly receding future glory: “tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther”, Americans assure themselves, only to find themselves “boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past”.

Indeed, Gatsby’s plan for the future is precisely to “repeat the past” by recovering “some idea of himself that had gone into loving Daisy … I’m going to fix everything just the way it was before”.

Neither Gatsby’s ambitions or the nation’s can stand much scrutiny. Even before his fall, Gatsby’s “dream […] was already behind him” in “the dark fields of the republic”, leaving a “foul dust” in its wake.

Still, what Nick most admires in Gatsby is his “heightened sensitivity to the promises of life” and Fitzgerald implies that this “extraordinary gift for hope” might be the essence of the American Dream.![]()

Sascha Morrell, Lecturer in English, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.