The link below is to an infographic that looks at why reading to kids 20 minutes a day is a good thing.

For more visit:

https://ebookfriendly.com/why-read-to-kids-20-minutes-day-infographic/

The link below is to an infographic that looks at why reading to kids 20 minutes a day is a good thing.

For more visit:

https://ebookfriendly.com/why-read-to-kids-20-minutes-day-infographic/

Sergio Macklin, Victoria University and Sarah Pilcher, Victoria University

Children from disadvantaged backgrounds, very remote areas, and Indigenous Australians are up to two times more likely to start school developmentally vulnerable than the national average.

In 2018, 21.7% of Australian five year olds (70,308 children) were not developmentally ready when they started school. And in Year 7, nearly 25% of students (72,419) didn’t have the required numeracy and literacy skills.

Our report, Educational Opportunity in Australia 2020, is the first to examine Australia’s performance against the goals set out in the Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Declaration, a national statement agreed to by Australian education ministers in 2019.

The statement aims for a quality education system for all young people, that supports them to be creative and confident individuals, successful learners and active and informed members of the community.

But our report finds students’ location and family circumstances continue to play a strong role in determining outcomes from school entry to adulthood.

While this crisis in educational inequality isn’t new, it’s likely to get a lot worse, as COVID-19 increases levels of student vulnerability and remote learning widens gaps in achievement.

The Alice Springs declaration sets two ambitious goals:

the Australian education system promotes excellence and equity. In part, this is about ensuring all young Australians have access to high-quality education, inclusive and free from any form of discrimination

all young Australians become confident and creative individuals, successful lifelong learners, and active and informed members of the community. This includes all children having a sense of self-worth, self-awareness and personal identity that enables them to manage their emotional, mental, cultural, spiritual and physical well-being.

The declaration was signed last year, and builds on previous ones signed in Hobart, Adelaide and Melbourne over three decades. It recognises the role education plays in preparing young people to contribute meaningfully to social, economic and cultural life.

Our report uses the best available data to paint a comprehensive picture of Australia’s performance against the above important goals.

It shows the gap in academic learning as well as other key areas, such as creativity and confidence, is clear from school entry and usually grows over time.

Analysis in our report tracked students’ learning from when they started school in 2009 to when they were in Year 5 in 2014. It showed that in literacy and numeracy for instance, the gap between the proportion of children from the most disadvantaged and advantaged families meeting relevant standards grew from 20.6 percentage points at school entry to 27.2 percentage points in Year 5.

The report also shows too many students in the senior years of school are not developing key skills. In 2018, 27.8% of 15 year olds (88,314) didn’t meet or exceed the international benchmark standards in maths, reading and science.

While some students receive the support they need to catch up to their peers, many don’t.

A lot of young people are also not developing the qualities needed to confidently adapt to challenges in adulthood and contribute to their communities.

The report shows that in 2017, 28.1% (110,410) of 23 year olds were not confident in themselves or the future and 29.9% were not adaptable to change and open to new ideas. It shows 38.1% (145,056) of 23 year olds were not actively engaged in their community and 33.2% were not keeping informed about current affairs.

Additionally, many young Australians are not being well prepared and supported to find and secure meaningful employment. Overall, according to the 2016 census, nearly 30% of 24 year olds (112,695) weren’t in full-time education, training or work.

Around half of all 24 year old Indigenous Australians, and one in three of the most disadvantaged Australians, were not engaged in any work or education, compared to 15% nationally.

This failure to address educational inequality reproduces and amplifies existing poverty across generations. It saps productivity, undermines social cohesion and costs governments and communities billions of dollars.

On an individual level, it hampers young people’s search for secure employment and is connected to poorer health and lower quality of life.

There are no quick ways to fix educational inequality, but there are several key improvements that will make a difference.

Closing gaps in participation and lifting the quality of early childhood education services — particularly in disadvantaged communities where services tend to be lower quality — should be one of our highest priorities. Early childhood education is critical to giving every child the best possible start. Evidence shows preschool raises children’s chances of being developmentally ready for school in key areas by around 12 percentage points.

Despite efforts through the Gonski reforms, there is still significant room to improve how Australia targets funding and support to schools with the highest level of need. We need to address the imbalance in resources between advantaged and disadvantaged Australian schools, which is the worst in the OECD.

This is not just about money, but building strong leadership and teaching capability in every school. High quality teaching is proven to be critical to improving student outcomes. We also need to support high quality use of data and assessment to tailor teaching to students’ needs, provide feedback and measure progress.

Read more:

How to get quality teachers in disadvantaged schools – and keep them there

Government projections show 90% of employment growth in the next four years will require education beyond school. This means we must prepare young people for an economy requiring higher levels of skill than ever. We need to rethink existing models of tertiary education to make it accessible to all students.

Addressing educational inequality is as much about what happens outside the classroom as inside. Nurturing every child’s development and well-being is best achieved through a partnership between schools, families, communities and other support services.

Australia cannot afford education systems that fail so many students. That’s not just in economic terms – because the cost of lost opportunity is even greater down the track – but also in human terms. We know the social and health costs of disengaging in education are significant.![]()

Sergio Macklin, Deputy Lead of Education Policy, Mitchell Institute, Victoria University and Sarah Pilcher, Policy Fellow, Mitchell Institute, Victoria University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that looks at the best children’s books.

For more visit:

https://www.npr.org/2020/08/31/905804301/welcome-to-story-hour-100-favorite-books-for-young-readers

The link below is to an article reporting on the winners of the 2020 New Zealand Book Awards for Children and Young Adults.

For more visit:

https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2020/08/13/155169/nz-book-awards-for-children-and-young-adults-2020-winners-announced/

Helen Joanne Adam, Edith Cowan University; Caroline Barratt-Pugh, Edith Cowan University; Libby Jackson-Barrett, Edith Cowan University, and Robert Stanly Somerville, Edith Cowan University

Global support for the Black Lives Matter movement isn’t only about standing up against the injustice done to George Floyd, or Indigenous Australians in custody. People are also standing up against the entrenched racism that leads to a careless approach towards the lives of people who aren’t white.

Research shows 75% of Australians hold an implicit bias against Indigenous Australians, seeing them negatively, even if this is unconscious. Children absorb this bias, which becomes entrenched due to messages in the media and in books, and continues to play out at school and the broader community.

Making sure children have access to books showing diversity is one step in breaking the cycle that leads to entrenched racism.

Children develop their sense of identity and perceptions of others from a very early age – as early as three months old. Because of this, young children are particularly vulnerable to the messages they see and hear in the media and in books.

Research over many years has shown books can empower, include and validate the way children see themselves. But books can also exclude, stereotype and oppress children’s identities. Minority groups are particularly at risk of misrepresentation and stereotyping in books.

First Nations groups are commonly absent from children’s books. Excluding the viewpoints, histories and suffering of First Nations Peoples can misrepresent history, and teach kids a white-washed version of the past.

Read more:

Captain Cook ‘discovered’ Australia, and other myths from old school text books

A world of children’s books dominated by white authors, white images and white male heroes, creates a sense of white superiority. This is harmful to the worldviews and identities of all children.

Evidence shows sharing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stories helps break down stereotypes and prejudice. And this, importantly, helps empower Aboriginal children and improve their educational engagement and outcomes.

But research suggests many classrooms have books that are monocultural literature, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander books are notably absent.

There are some encouraging signs, with an increase in the publication of books by and about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. We are also seeing bookshops and publishers reporting a rise in demand for books on race and racism.

This can also help adults become informed about Australia’s colonial history. Reading these books can help challenge their own unconscious biases and misunderstandings.

Read more:

Bias starts early – most books in childcare centres have white, middle-class heroes

The challenge for teachers and parents is to access suitable children’s books and share them with the children in their care. We can use these stories as a foundation for conversations about culture and community.

This can help to drive change and support reconciliation.

Creating Books in Communities is a pilot project run by the State Library of Western Australia that helps create books with families about their everyday experiences. These books represent the families’ culture and language.

Projects like these are another way we can recognise and extend the voices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Another project, On Country Learning, involves children and teachers learning through culture alongside Aboriginal elders. A preliminary review of the program shows it enriches teacher knowledge and motivates all children to learn.

Reading and listening to the stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples can help teachers gain important knowledge and understanding. This helps them effectively engage with and teach Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students.

Read more:

9 tips teachers can use when talking about racism

And it helps them teach all students about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages, histories and cultures.

To see real and lasting change children need everyday story books with heroes and characters that reflect their diverse backgrounds. To help this happen we can support groups such as the We Need Diverse Books Movement and LoveOZYA , which actively call for and promote diverse books for young people.

Affirmation of all children’s culture, language and identity at this pivotal time in world history is critical to the future of all our children.

Parents and teachers can source Aboriginal literature from websites such as: Magabala Books, IAD Press, Aboriginal Studies Press, Fremantle Press, UWA Publishing, BlackWords, Batchelor Institute Press.![]()

Helen Joanne Adam, Senior Lecturer in Literacy Education and Children’s Literature: Course Coordinator Master of Teaching (Primary), Edith Cowan University; Caroline Barratt-Pugh, Professor of Early Childhood, Edith Cowan University; Libby Jackson-Barrett, Senior Lecturer, Edith Cowan University, and Robert Stanly Somerville, Head of Teaching and Learning, Kurongkurl Katitjin Centre for Australian Indigenous Education and Research, Associate Professor, Edith Cowan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that looks at the importance of reading to the kids.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2020/04/30/reading-aloud-to-kids/

Shih-Wen Sue Chen, Deakin University; Kristine Moruzi, Deakin University, and Paul Venzo, Deakin University

With remarkable speed, numerous children’s books have been published in response to the COVID-19 global health crisis, teaching children about coronavirus and encouraging them to protect themselves and others.

Children’s literature has a long history of exploring difficult topics, with original fairy tales often including gruesome imagery to teach children how to behave. Little Red Riding Hood was eaten by the wolf in a warning to young ladies to be careful of men. Cinderella’s stepsisters had their eyes pecked out by birds as punishment for wickedness.

More recently, picture books have dealt with issues including September 11, the Holocaust, environmental issues and death.

But this wave of coronavirus books is unique, being produced during a crisis rather than in its aftermath.

Many have been written and illustrated in collaboration between public health organisations, doctors and storytellers, including Hi. This is Coronavirus and The Magic Cure both produced in Australia.

These books explore practical ways young children can avoid infection and transmission, and provide strategies parents can use to help children cope with anxiety. Some books feature adult role models, but the majority feature children as heroes.

The best of these books address children not just as people who might fall ill, but as active agents in the fight against COVID-19.

Coronavirus: A Book for Children

Written in consultation with an infectious diseases specialist and illustrated by Axel Scheffler of The Gruffalo, this nonfiction picture book offers children information about transmission, symptoms and the possibility of a cure, reassuring readers that doctors and scientists are working on developing a vaccine.

The last few pages answer the question “what can I do to help?”

Coronavirus: A Book for Children shows a diversity of characters taking action to manage the effects of the virus. Children are told to practice good hygiene, not to disturb their parents while they are working from home and keep up with their schoolwork.

It is also hopeful: reinforcing the idea that the combination of scientific research and practical action will lead to a point when “this strange time will be over”.

My Hero is You! How kids can fight COVID-19

Written and illustrated by Helen Patuck, My Hero is You! is an initiative of a global reference group on mental health, and is a great book for parents to read with their children.

Sara, daughter of a scientist, and Ario, an orange dragon, fly around the world to teach children about the coronavirus.

Ario teaches the children when they feel afraid or unsafe, they can try to imagine a safe place in their minds.

Based on a global survey of children and adults about how they were coping with COVID-19, My Hero is You! translates the results of this comprehensive survey into a reassuring story for kids experiencing fear and anxiety. It also acknowledges the global nature of the health crisis, showing children they are not alone.

The Princess in Black and the Case of the Coronavirus

The Princess in Black is an existing series, with seven books published since 2014 and over one million copies sold. In the books, Princess Magnolia enlists children to help with a problem she cannot defeat alone: here, of course, that problem is coronavirus.

For fans of the series, Magnolia and her pals are familiar characters encouraging readers to solve the problem of coronavirus by washing their hands, staying at home, and keeping their distance.

The Princess in Black shows a deft use of humour to introduce children to complex ideas in a familiar and friendly manner.

Children’s books have often sought to entertain and educate children at the same time. The immediacy of these books, with their practical solutions and strategies for children to manage fears and anxieties about sickness and isolation, is a phenomenon we haven’t seen before.

With free online distribution and simple messages, these books present children with individual actions that have both personal and collective benefits.

Importantly, the heroes identified in these stories include children themselves. Their fears are acknowledged, but at the same time they are told they can fight the virus successfully.

A frequently updated list of children’s books on the pandemic is available from the New York School Library System’s COVID-19 page.![]()

Shih-Wen Sue Chen, Senior Lecturer in Writing and Literature, Deakin University; Kristine Moruzi, Research fellow in the School of Communication & Creative Arts, Deakin University, and Paul Venzo, , Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that takes a look at ideas for storing books for kids.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2020/03/30/kids-book-storage-ideas/

The links below are to articles reporting on free audiobooks on offer from Audible for kids while schools are closed.

For more visit:

– https://ebookfriendly.com/hundreds-audible-audiobooks-free-coronavirus-pandemic/

– https://goodereader.com/blog/audiobooks/audible-offering-hundreds-of-kids-audiobooks-for-free

– https://bookriot.com/2020/03/19/audible-launches-audible-stories-for-children-and-teens-while-school-is-out/

George Rudy via Shutterstock

Mimi Thebo, University of Bristol

Stories can be mirrors that help young people express feelings about a given situation. They give children a vocabulary for what is happening. But, because of how fiction works in the brain, stories can also be windows. When we read fiction, we inhabit other bodies and feel the concerns of other people. This helps young people to develop empathy – but has another profound effect. Reading stories makes us feel experienced and increases resilience.

I’ve chosen some wonderful books that all function both as mirrors and windows for children as the world faces the effects of Coronavirus. They are beautifully written and/or illustrated and should fire young imaginations, while comforting the whole family.

This is a beautiful picture book – sparse of text – with lush landscapes in Sean Tan’s magical style. The reader loses themselves in pages that are achingly evocative of yearning, loss and wonder in a kind of heady cocktail of intense emotion, boredom and stoicism.

Dark leaves fall in our character’s bedroom, but by the end, they have coalesced into a beautiful red tree.

There is space here for even a very young reader to express what they think is happening page by page. The art could stimulate imitation. I can also imagine making a little red tree trunk and branches and adding a leaf to it, day by day.

There is very little reading to be done, so a slightly older child could also “read” it to a younger one.

Antonia Barber sets her classic story on the Cornish coast. The narrative is about a cat who saves the day when her community is threatened. It is wordier than many picture books, but narrated by the cat in clear, beautifully written prose – it’s a pleasure to read aloud.

Nicola Bayley’s illustrations are engaging and immersive – who wouldn’t like to go to the seaside right now? – and the characters easily inspire affection.

Touching on concepts of scarcity and sacrifice, this is a very empowering story for a young listener or reader. The smallest character in the story is the hero who saves everyone – by singing. It would be easy to live in this story for a while, going fishing from the laundry basket, practising storm singing, repeating some of the turns of phrase.

The illustrations are inspiring for young artists and could also be the basis of remembering visits to the seaside, pretend beach picnics or natural history lessons.

A trip to Tove Jansson’s Moominland always makes everything better. Here, the family flee from an approaching comet, meeting many favourite characters on the way.

The much-beloved Moomins are eccentric hippo-like people, very accommodating of difference and otherness. That said, many of the characters have their little ways, and being accommodating isn’t always comfortable. The realism of the relationships gives even the silliest of Jansson’s stories the texture of real life.

Quirky line drawings are immensely endearing and the story, while exciting with elements of real fear, never feels as if it will end badly. The language is fun, with word play and characters’ attitudes and, again, the child is the hero. It’s not hard to draw a Moomin, and there are endless opportunities for drama. Year twos or threes can probably read it to themselves, with someone on hand for the tricky bits, but it’s fun enough to engage older children, and silly enough for littlies.

Tiffany Aching comes from chalkland, where nobody has it easy, and everyone works hard. When a rift opens on her doorstep and her despised little brother is taken, she discovers she’s not ordinary, after all. Armed with a cast-iron frying pan, she takes on the full force of Fairyland.

This is a riotous out-loud read from the late Terry Pratchett, featuring a tribe of “pictsies” who speak in a Scottish accent that sounds a lot like the stand-up comic Billy Connolly. Tiffany’s gran has recently passed away – and the danger feels quite real – but we know that Tiff will get us through. She certainly does, battling forces of depression and self-doubt to do so – another young leader in a time of community danger. Even hardened teenagers might smile at the best bits and tweens will devour it whole. Children as young as six or seven can follow along.

The narrative is a role-play bonanza and there are opportunities to investigate British folklore, identities in the United Kingdom and gender roles. Illustrations in the text might inspire art and mapping the settings would be an interesting exercise. Further adventures of some of the characters could be written, and geography lessons about chalk grassland would be easy to work in.

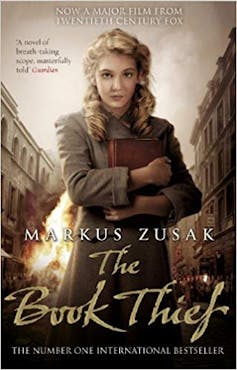

For resilient older children and teens, Markus Zusac’s story is set in a time of many lives lost – Germany during the second world war – and narrated by Death. It is gorgeously written (an international bestseller, adapted for film) and, while the subject matter is difficult, the narrative pulses with life and hope.

For a young person engaged with current events, questioning authority and impatient of parental efforts to shield them from the grimmer elements of our current reality, this book could be a lifeline.

Liesel Meminger is illiterate when the story begins, but takes a book that has been dropped at her brother’s graveside. As she begins to read and to leave childhood behind, she steals many more books. Love, death and the importance of even futile actions inform the story of Liesel’s coming of age and provide ways of thinking about what it means to be human.

This could be read together silently, perhaps taking chapters in turn, rationed out as a treat for discussion or not. It’s a natural accompaniment to history lessons, geography, or some online German instruction and watching the film could lead to a discussion of adaptation. But perhaps you could just leave a copy of it out for anyone who needs it to find and make their own.

Many of these titles are available electronically, but local bookshops are delivering and posting orders. After all, there’s nothing more comforting than snuggling behind the protective embrace of an open book.![]()

Mimi Thebo, Reader in Creative Writing, University of Bristol

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.