Jared Rice/Unsplash

Ian Hesketh, The University of Queensland and Henry-James Meiring, The University of Queensland

When Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution was first published in On the Origin of Species in 1859, the book was conspicuously silent about how his theory applied to humans.

Darwin believed the subject of human evolution was so “surrounded with prejudices” he was determined to avoid it entirely.

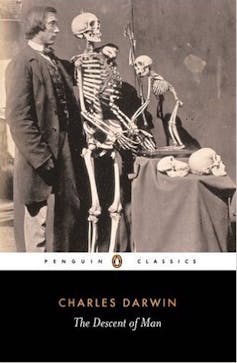

It was only when he became frustrated by the way others conceived of human evolution that he took up the subject himself. His two-volume The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex was published on 24 February 1871.

Revisiting this work 150 years on, it is striking how some of Darwin’s most radical claims — such as humanity’s ape-like ancestry — are now taken for granted while some of his other views were clearly embedded in Victorian racial and gender stereotypes.

Read more:

Guide to the classics: Darwin’s On the Origin of Species

Sexual selection

Darwin’s objective in Descent was threefold: to consider whether humans were descended from a pre-existing form; to consider the nature of human development; and to consider the differences between the “human races”.

In coming to terms with these issues, Darwin focused on the theory of sexual selection.

Darwin’s earlier theory of natural selection explained how the struggle for limited resources led to adaptations that were beneficial to certain individuals of the same species at the expense of others.

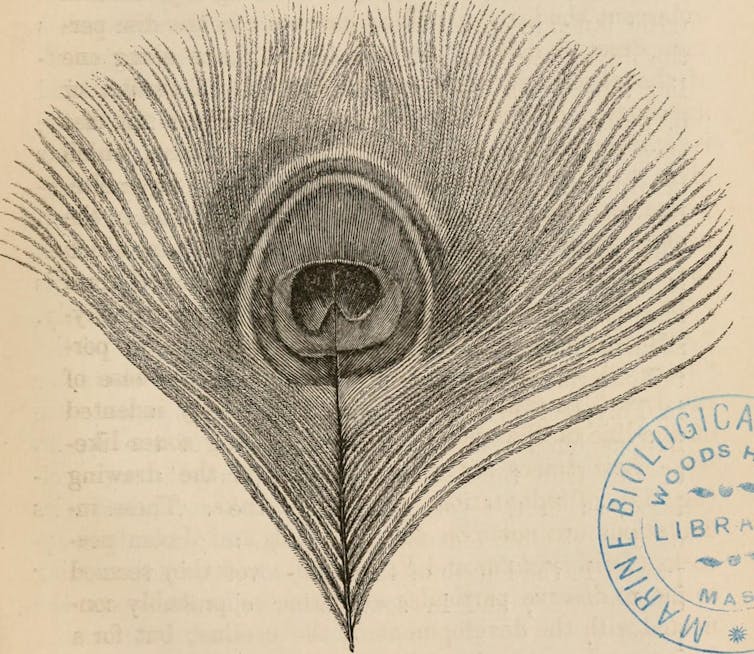

Wikimedia Commons

Sexual selection, in contrast, explained how the struggle for mates led to adaptations with no survival benefit. The bright plumages of male birds of paradise and the spectacular tail of the peacock were a product of mate choice by female birds, he wrote.

A similar process, he theorised, explained the development of specialised weapons for battle, such as the large horns of beetles: a result of males struggling against one another to secure mates.

Applying this principle to humans, Darwin argued that in the early stages of humanity’s development, men took the power of selection away from women. Men struggled against other men to select their mates, he wrote, and so became stronger and more intelligent over time, while women became more nurturing in their pursuit to attract mates through the cultivation of fashion.

It is not difficult to see how this theory of sexual selection naturalised Victorian gender relations.

Read more:

How Darwin’s sexual selection theory co-stars in ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’

The development of the races

For Darwin, sexual selection also explained how different human races had developed.

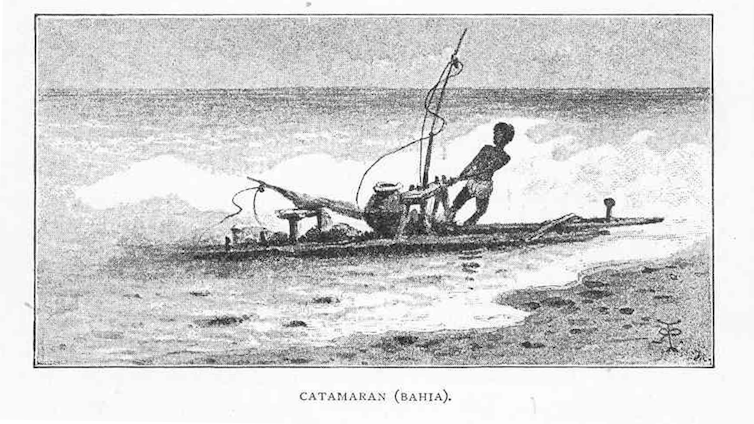

While he was committed to the theory of monogenism, believing humans were a single species, he also adhered to a racial hierarchy. As historian of science Evelleen Richards shows in her recent book, Darwin’s encounters with Indigenous peoples during his Beagle voyage, circumnavigating the globe between 1831 and 1836, led him to perceive vast physical and intellectual differences between the human races.

Freshwater and Marine Image Bank at the University of Washington

He came to believe many of those differences could be explained by the processes of sexual selection. Differences in skin colour were, for Darwin, the result of diverse aesthetic preferences, which subsequently led to the development of distinct races. And as the races diverged, they were further shaped by inherited customs and social practices.

By accepting a racial hierarchy in this scheme, Darwin believed Indigenous peoples, or “savages” as he called them, represented “early stages” in human development.

In the final observation of the book, Darwin confessed he would rather be related to a “heroic little monkey” than to a “savage who delights to torture his enemies”.

His deeper message, however, was that readers should be consoled by the fact some of the nobler qualities of humans were shared by many of the great apes — even if they seemed to be absent from humanity’s “early stages”.

What makes humans moral?

The Descent of Man included three chapters dedicated to the subject of mind and morals. Darwin aimed to show there was “no fundamental difference between man and higher mammals” in their moral and mental faculties.

His moral theory relied heavily on animal observations, including those of dogs, apes, and even bees. He insisted humans shared the capacity to feel guilt, shame, and compassion with other social animals — therefore moral conscience was not unique to humans.

Darwin’s theory rejected essentialist and religious categories of “right” and “wrong”. He postulated different animals developed different moral systems depending on their environment and social structures, famously using bees as an example.

If, for instance, to take an extreme case, men were reared under precisely the same conditions as hive-bees […] our unmarried females would, like the workerbees, think it a sacred duty to kill their brothers, and mothers would strive to kill their fertile daughters; and no one would think of interfering.

Morality was the product of factors related to the struggle for survival and reproduction, and not divinely ordained.

Eric Ward/Unsplash

Reception

Even though plant and animal evolution was largely accepted by the scientific community at the time, the subject of human evolution was still highly contentious. Darwin’s views were heatedly debated in the press and in public.

A reviewer for the Edinburgh Review observed:

no book of science has excited a keener interest than Mr. Darwin’s new work on the ‘Descent of Man.’ In the drawingroom it is competing with the last new novel, and in the study it is troubling alike the man of science, the moralist, and the theologian. On every side it is raising a storm of mingled wrath, wonder, and admiration.

By the end of 1871, the work was translated into Dutch, German, Italian and Russian.

Despite its commercial success, The Descent of Man was heavily criticised. At the beginning of 1872, Darwin lamented “hardly any naturalists” agreed with him on sexual selection.

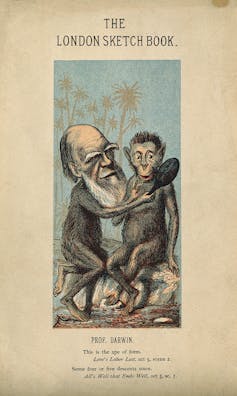

Wellcome Collection, CC BY

Most naturalists felt Darwin attributed too much power to female choice, and they rejected the idea other animals could possess an aesthetic sensibility.

It was Darwin’s analysis of morality, however, that caused the greatest outrage. He stood accused of undermining the foundation of Christian society by advocating moral relativism.

Leading feminist Frances Power Cobbe rejected Darwin’s theory of morality as “simious”, while The Times thundered Darwin’s ideas could encourage “the most murderous revolutions”.

Darwin received hate mail from offended readers like Mr. D. Thomas, who referred to him as a “venerable old Ape”. Darwin began to be regularly caricatured as an ape in the press.

Descent today

Certain aspects of Descent hold up well, such as Darwin’s speculation humans originated from Africa, as evidenced by multiple fossil discoveries in the mid-20th century, notably by Mary and Louis Leakey.

Wellcome Collection

Many of his controversial insights in relation to morality have been central to recent debates about “evolutionary ethics” among moral philosophers considering the relationship between our understanding of morality and evolution.

And his theory of mind and morals informed the development of multiple scientific disciplines in the 20th century, including evolutionary psychology, neuroscience, and psychoanalysis.

The same cannot be said about Darwin’s theory of sexual selection. While the idea of “female choice” has been revived several times, such as in Robert Trivers’s parental investment theory which argues the sex that takes on the primary caring role has the greatest choice in a mate, there is very little consensus on the relationship between mate choice and beauty.

Moreover, most evolutionists consider male combat — as Darwin wrote about in horned beetles — a form of natural selection, rather than sexual selection.

And when it comes to Darwin’s general views of race and gender, he very much appears a man of his time and social background.

Today, what is most compelling about The Descent of Man is how Darwin’s portrayal of humans was made within the context of a system of evolution that applied equally to all of nature. At a time when other evolutionists stressed humanity’s uniqueness, Darwin instead sought to uncover man’s “lowly nature”.![]()

Ian Hesketh, ARC Future Fellow and Association Professor, The University of Queensland and Henry-James Meiring, PhD Candidate, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.