The History of the Waldenses by James Aitken Wylie

The History of the Waldenses by James Aitken Wylie

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Tag Archives: book review

Finished Reading: Red Queen (Book 0.1) – Queen Song by Victoria Aveyard

Guide to the classics: Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass and the complex life of the ‘poet of America’

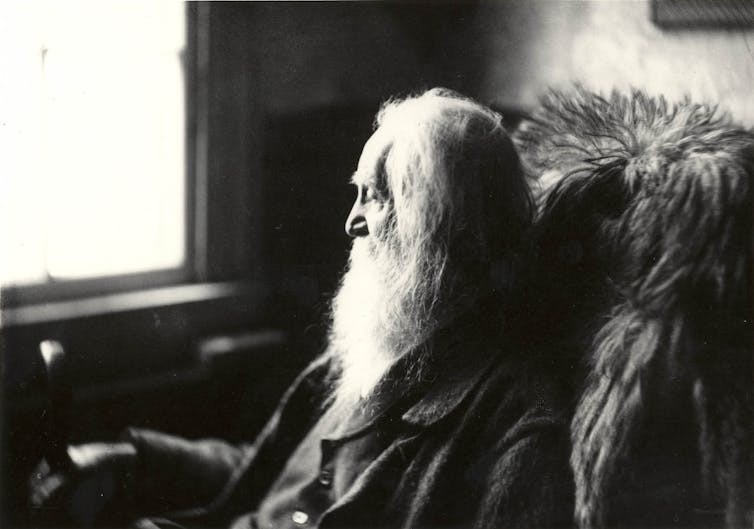

Samuel Murray/Wikimedia Commons

Carolyn Masel, Australian Catholic University

This is a longer read. Enjoy!

This year marks the 200th anniversary of the birth of Walt Whitman, America’s most admired poet. Celebrations will be especially joyful around his birthday on May 31 and in New York City, whose citizens were often depicted in his poems. But the poetry many people now love won him notoriety before it won him fame.

Whitman’s life was interesting and varied. He was born in 1819 and grew up in and around Brooklyn, moving often as his family tried to make money from farming and real estate. His formal education ended when he was 11. He worked by turns in Manhattan and Brooklyn as a printer’s apprentice, a schoolteacher and a newspaper publisher, before resolving to become a writer.

Having had some success – a novel and newspaper pieces – he became chief editor of the Brooklyn Eagle, but lost this position when his opposition to the spread of slavery clashed with the views of the newspaper’s owner. Luckily, an opportunity arose to work on a newspaper in New Orleans. Whitman enjoyed this different culture, but never lost his horror of slave auctions.

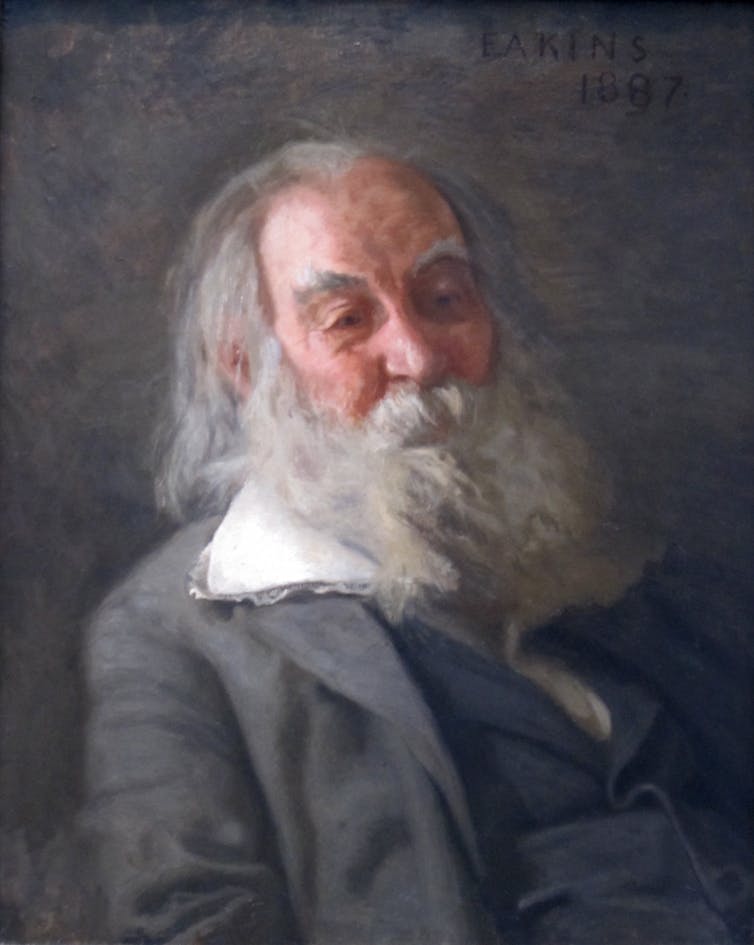

Thomas Eakins/Wikimedia Commons

On learning his brother George might have been injured during the Civil War, Whitman travelled to Washington DC and Fredericksburg, Virginia, to look for him. Fortunately, George’s wound was only superficial, but Whitman stayed on in Washington as a nurse, where he attended to sick, maimed and dying soldiers.

Working in field hospitals, Whitman’s health deteriorated, and at the age of 53 he suffered a stroke. Although he made a partial recovery, he was cared for by friends until he died almost 20 years later in March 1892. By then, he was admired for his writing in England, but the thousands who lined the streets in New Jersey for his funeral procession were probably more curious about his enormous tomb, which he had designed himself, than his writing.

Bart E/flickr, CC BY

Whitman’s innovation

We don’t know how or why Whitman began to invent his extraordinary poetry. In 1842 he listened to “The Poet”, a lecture in which philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson called for a national bard who could write about the US in all its diversity. But Whitman’s daring originality seems more than a mere response to Emerson’s demands.

It is clear he thought of his book of poems, Leaves of Grass, as an experimental project. He took the opportunity of having the best compositors, the Rome brothers, typeset his poems, and he supervised the work closely, revising his poetry to fit the page. He even set about ten pages of the type himself.

The book’s long non-rhyming lines are reminiscent of bible verses. Each seems to correspond with a single breath or a single gesture. Words or phrases are often repeated at the beginning of a series of lines, building up a rhythmical pattern. However, Whitman is careful to break the pattern before it can become mere rhetoric. The reader is constantly being called to attention:

Smile O voluptuous cool-breath’d earth!

Earth of the slumbering and liquid trees!

Earth of departed sunset – earth of the mountains misty-topt!

Earth of the vitreous pour of the full moon just tinged with blue!

Earth of shine and dark mottling the tide of the river!

Earth of the limpid grey of clouds brighter and clearer for my sake!

Far-swooping elbow’d earth – rich apple-blossom’d earth!

Smile, for your lover comes. (“Song of Myself”, canto 21)

Leaves of Grass was Whitman’s sole book of poetry. Rather than publish several collections containing new poems, he revised and expanded this single volume, so that the first edition of 12 poems eventually became a thick book of close to 400 poems.

There are six editions of the book (nine, if you count different type-settings). As soon as one was published Whitman would revise, regroup and add to the poems, treating the published book as a manuscript to be edited and republished.

The overall result of this practice is that Whitman’s poetry is seen always to flow from a single being; it is as unified and as singular as the man who made it.

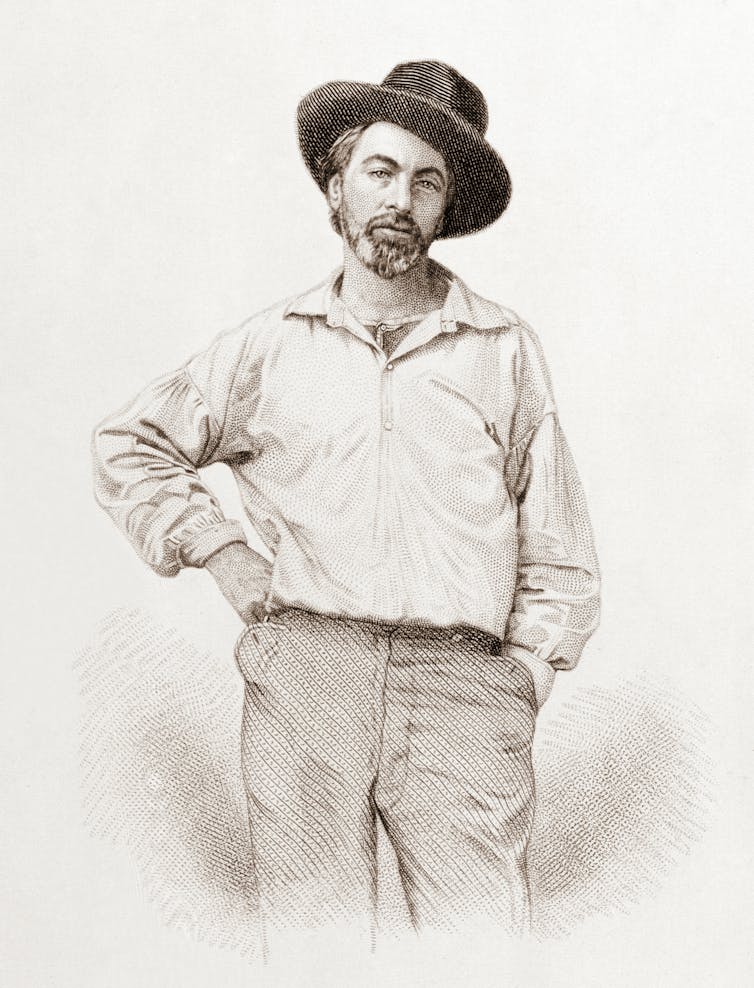

The first edition of Leaves of Grass did not even contain the author’s name on the title page, but he was instantly recognisable from his picture on the frontispiece – a working man in his prime, open-shirted, hat on the back of his head, hand on hip, looking straight out at the reader.

Wikimedia Commons

The poet of democracy

Emerson’s influence – or Whitman’s agreement with Emerson – can be seen in Whitman’s insistence on democracy as a central value of American society. People are equal, according to Whitman, because we are all mortal; moreover, we all have immortal souls.

In “Song of Myself”, we can see the connection between democracy, equality and immortality in the symbolic use of grass, which grows everywhere:

[…] I guess it is a uniform hieroglyphic,

And it means, Sprouting alike in broad zones and narrow zones,

Growing among black folks as among white,

Kanuck, Tuckahoe, Congressman, Cuff, I give them the same, I receive them the same. […]Tenderly will I use you curling grass,

It may be you transpire from the breasts of young men,

It may be if I had known them I would have loved them,

It may be you are from old people, or from offspring taken soon out of their mothers’ laps,

And here you are the mothers’ laps. […]What do you think has become of the young and old men?

And what do you think has become of the women and children?They are alive and well somewhere,

The smallest sprout shows there is really no death […]All goes onward and outward, nothing collapses,

And to die is different from what any one supposed, and luckier.

In this passage the grass signifies equality, by making no distinction where it grows. A “hieroglyphic” symbol might need an expert – such as Whitman – to translate it, but it grows “uniform[ly]”, giving everyone the same rights and the same chances to mean something in the great poem that is America, as Whitman saw it.

Poet of the soul

As a result of Whitman’s habit of revision, we can witness the growth of many poems. The Sleepers, generally agreed to be among his finest, was worked on over the course of his career.

It is one of his most ambitious poems, with a triumphant ending that seems genuinely earned. It poses questions about the limitations of a single human life. How can one life, or one death, or one gender, be enough for a man, a poet, consumed by curiosity?

Goodreads

Whitman wants to dream every sleeper’s dream, be every sleeper’s lover, know every person’s meaning in the larger scheme, live everyone’s life and die everyone’s death.

In the third section of the poem, he envisages a beautiful swimmer, who comes to grief on rocks and dies. His body is then retrieved and laid out in a barn, with others, to be mourned just as the slain soldiers in the Revolutionary War (1775-83) were mourned by General Washington.

A Native American woman comes to visit the man’s mother, and then goes on her mysterious way, before everyone else returns to their rightful place: immigrants return home, colonial masters return to their countries of origin, the dead (including the beautiful swimmer), those waiting to be born, the sick, the disabled, the criminal are all likened to one another and restored in sleep.

At the end of the poem, all of the restored sleepers begin to awaken, an event described in terms of reconciliation and resurrection:

The sleepers are very beautiful as they lie unclothed,

They flow hand in hand over the whole earth from east to west as they lie unclothed,

The Asiatic and African are hand in hand, the European and American are hand in hand […]The felon steps forth from the prison, the insane becomes sane, the suffering of sick persons is reliev’d,

The sweatings and fevers stop, the throat that was unsound is sound the lungs of the consumptive are resumed, the poor distress’d head is free […]

Stiflings and passages open, the paralyzed become supple,

The swell’d and convuls’d and congested awake to themselves in condition,

They pass the invigoration of the night and the chemistry of the night, and awake. (Canto 8)

Only at the end of the poem does Whitman state that he has been previously afraid to trust himself to the night, but that now he is at peace with the rhythm of night and day, sleeping and waking, which governs the world.

Poet of the body

Whitman’s poetry was initially unpopular. Not only was his new verse form considered outlandish, but his insistence on the worthiness of the body put him beyond respectability. Emerson originally endorsed him, “greet[ing him] at the beginning of a great career”, but when Whitman published Emerson’s approving letter without permission in the next edition of the book, he put Emerson in an awkward position.

Emerson tried to dissuade Whitman from publishing explicit poems about sex and sexuality, but Whitman did so anyway. The 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass introduced a Children of Adam section, depicting robust heterosexual love, and a Calamus section, which celebrated love between men:

Not heat flames up and consumes,

Not sea-waves hurry in and out,

Not the air delicious and dry, the air of ripe summer, bears lightly along white down-balls of myriads of seeds,

Wafted, sailing gracefully, to drop where they may,

Not these, O none of these more than the flames of me, consuming, burning for his love whom I love […]

There were a few enthusiastic anonymous reviews for Leaves of Grass, but they were written by Whitman. His friends William Douglas O’Connor and John Burroughs allowed Whitman to make bold claims for his poetic achievements under their names. One pamphlet, ostensibly by O’Connor, was called The Good Grey Poet, an image of wholesomeness that went some way toward transforming and boosting Whitman’s image. Eventually, in 1881, Whitman had the opportunity to publish an edition of his book with a major publisher, Osgood.

However, no sooner had 1,500 copies of this definitive edition been printed than the publisher had to withdraw it, under threat of litigation for promoting obscenity. Then, in 1882, Leaves of Grass was banned in Boston. Fortunately, he was taken up by another publisher, and made more than $1000 in royalties on this edition.

Whitman’s overtly homoerotic poems won him friends as well as enemies. The English socialist writer and reformer Edward Carpenter visited him twice, and Oscar Wilde was also pleased to meet him. John Addington Symonds, an English poet and critic, wrote to Whitman over many years, urging him to state explicitly what he meant by the love of comrades.

At last Whitman emphatically disavowed any claim made by Symonds about the possibly sexual nature of the Calamus poems and stated that he had fathered six children. No evidence has been found to substantiate this claim.

Only after his death were Whitman’s romantic letters to streetcar conductor Peter Doyle published. Today Whitman is claimed as a champion of same-sex love, although whether or not it was consummated is still a matter of debate and probably unknowable.

Charley Lhasa/flickr, CC BY-NC-SA

Whitman today

In one of the appraisals that Whitman ghost-wrote, he claimed to be better appreciated across the Atlantic than he was in America. There is truth in this: a censored English edition had found its way to a band of fervent supporters in industrial Bolton, near Manchester. They sent him a birthday message and ten pounds, and eventually two of them, J. W. Wallace and Dr John Johnson, went to visit the poet, by then gravely ill.

A lively transatlantic correspondence ensued that lasted long beyond the death of the poet and the two leaders of the Bolton Whitman reading group. Whitman’s birthday is still celebrated with a walk led by Bolton Socialist Club members.

The transformation of Whitman from shunned outsider to national poet-hero happened in fits and starts. Whitman’s own critical efforts and those of his transatlantic disciples began it. Then Whitman’s “spiritual son”, Horace Traubel, wrote a nine-volume work called With Walt Whitman in Camden, published between 1906 and 1996, designed to make Whitman’s thought more generally known.

Wealthy collectors of Americana began to exhibit the various editions of Whitman’s books. Readers began to appreciate Whitman’s insistence on the body and the value he placed on manly love. Whitman’s poetry began to be studied wherever American literature was taught, and he was taken up by popular culture.

Whitman’s birthplace in Huntington, New York, is now a museum, close to the Walt Whitman Shops on Walt Whitman Road. You can take a tour through his last residence – the only house he ever owned – in Camden, New Jersey.

He is now considered the father of free verse (although he was not the first poet to use it), the father of modern poetry, and, according to one critic, the “imaginative father and mother” of every American, whether a poet or not.

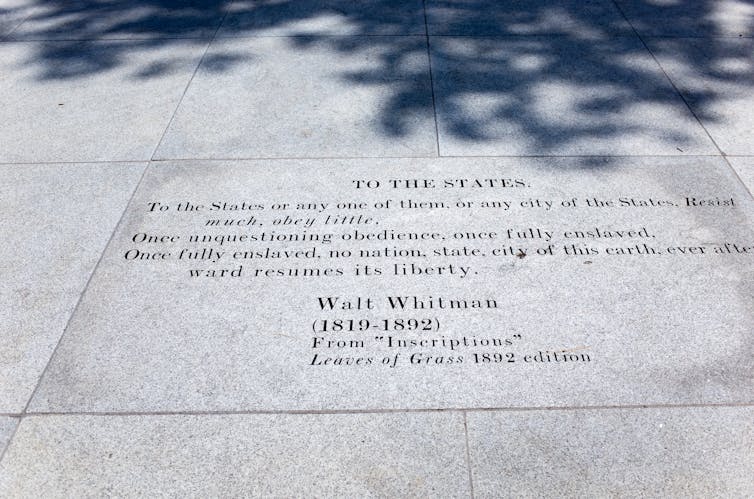

Whitman is also recognised with parks in Washington DC and New York. Among the most moving tributes is the Dupont Circle train station in Washington DC, which contains an inscription from his poem “The Wound Dresser”.

Originally written about the Civil War, these lines in their new context become a tribute to those who cared for sufferers during the AIDS crisis. One senses that the poet would be gratified at last to be given the recognition craved by this generous, embracing imaginative personality.![]()

Carolyn Masel, Lecturer in Literature, Australian Catholic University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Inside the story: writing trauma in Cynthia Banham’s A Certain Light

Dean Lewins/AAP

Tess Scholfield-Peters, University of Technology Sydney

Why do we tell stories, and how are they crafted? In a new series, we unpick the work of the writer on both page and screen.

Former Fairfax journalist and lawyer Cynthia Banham voices the silenced pain of generations in A Certain Light, her evocative, hybrid work of docu-memoir.

In an effort to process the trauma she experienced while on assignment more than ten years ago – a plane crash over Indonesia claimed both her legs and left 60% of her body covered in full thickness burns – Banham locates her own experience within her wider family’s narrative.

Banham’s memoir was released in 2018. Her story was once again in the news earlier this year, when Eddie McGuire mocked her pre-match coin toss at an AFL game (McGuire later apologised and said his comments were not about Banham).

In the book, Banham confronts the impact of the accident on her identity, and the ways in which her own resilience can be traced backwards through her heritage. She writes of her family: “We were shaped by each other’s trauma, just like we were shaped by each other’s love.”

Her voice shifts between the investigative (she incorporates historiography, images, documents, footnotes and parentheses) and the insightful and emotional first person. Yet her journalistic attention to detail is constant. Woven together, these voices comprise her fragmentary memoir, an arduous journey into the past and ultimately, resolution.

Allen & Unwin

Banham says A Certain Light is written for her young son, so he will one day know about his family’s history. The book begins with an epistolary prologue that speaks directly to him, predominantly through first person but sometimes in second.

We are invited by Banham into the intensely personal space of the text. She reveals to us her maternal indecision – the desire for her son to know, yet be shielded from, her trauma’s painful excesses.

Banham writes: “Will you, my son, grow up with memories of your mother’s suffering, feeling that you are somehow my compensation?” The first of many rhetorical questions throughout the text reminds us of her vulnerability, and the fraught task of communicating trauma through generations.

Connected narratives

Banham’s painful telling of her rehabilitation after the crash is threaded through other, broader stories of the past, an act of deflection perhaps signifying the difficulty endured in writing about the crash itself.

She retraces the trauma narratives of her grandfather, Alfredo; Alfredo’s sister, Amelia; and Banham’s mother, Loredana. She collects memories from family members across Europe, and artefacts and documents she has chosen to incorporate into the text, reflective of her own pieced-together family narrative.

The images are haunting at times and lend an immense gravity to Banham’s storytelling. Connecting stories of suffering to a face or a real artefact allows the reader to explore her own empathic ties with the story.

Banham finds a connection between the experiences of these relatives and her own. While her grandfather’s plight as an Italian prisoner of war in Nazi Germany is of course different to her own experience, Banham draws effective comparisons.

For example, she likens her thirst immediately after the plane crash as she waited, unable to move, in a foreign hospital hallway, to the excruciating thirst felt by victims of war.

In her research she encounters an image of German soldiers who had lost their legs. “War wounds”, she writes, “how did I end up with war wounds?” These comparisons show a lingering resonance of war in her mind, of the shared, transcendental suffering that connects generations.

Through her mother’s story as an Italian immigrant to Australia during the 1950s, Banham connects to a deep feeling of shame – the shame of difference, of abnormality. Shame was so innate that her mother was reluctant to let the surgeons amputate Banham’s legs in life-saving surgery, for fear of what her daughter’s life might be like without a “normal” body.

Banham leans painfully into her trauma in the final chapter of the book, titled Crashing. She revisits the site of the plane crash, and the days immediately before and after – the most distressing moments.

Weda/EPA

Tension builds as she recalls a handful of details: the description of her hotel room; the clothes she chose to wear that morning (might her life be different now if she had worn pants instead of a skirt?); the trivial pre-flight conversation she had with fellow journalists about Indonesia’s air crash record.

The actual recount of the crash is surreal. Banham writes: “Shit, I was thinking. Is this really happening? Then: Oh God.” On the next page: “Shit, actually, this could be it, this could be the end, maybe this is how I am going to die.”

The terror Banham experienced in those moments is beyond comprehension, and yet the incredibly human, common thoughts of panic incite an immense sense of empathy in the reader. It reminds us this could happen to anyone.

This is Banham’s second book – her first, Liberal Democracies and the Torture of Their Citizens, was derived from her PhD undertaken at the Australian National University several years after her accident.

A Certain Light reconciles the woman she was before the plane crash with the woman who writes this text. Banham explores the fragility of memory and the shared longing to know the stories of family members who can no longer speak, or perhaps do not want to.

“Memory is fluid, malleable, untrustworthy”, Banham writes, yet ultimately it’s memory that has created her narrative, her identity reclaimed from trauma. A Certain Light is a reminder that despite even the greatest tragedy, time moves on and there is light in the darkness – if we choose to see it.![]()

Tess Scholfield-Peters, PhD candidate in Creative Arts, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Finished Reading: Red Queen (Book 2) – Glass Sword by Victoria Aveyard

Finished Reading: The Saxon Stories (Book 1) – The Last Kingdom by Bernard Cornwell

Finished Reading: Red Queen (Book 1) – Red Queen by Victoria Aveyard

Inside the story: Leigh Sales, ordinary days and crafting empathy ‘between the lines’

Sue Joseph, University of Technology Sydney

Why do we tell stories, and how are they crafted? In a new series, we unpick the work of the writer on both page and screen.

Decades ago, American journalist and screenwriter Dan Wakefield published Between the Lines: A reporter’s personal journey through public events. In terms of reflection and consideration, Wakefield was years ahead of his time. He writes of the “shadows that lurk behind the printed word … We journalists are trained by the custom and conventions of our craft to remain out of sight, pretending not to be there but simply to know”.

He then returns to many of his own pieces of journalism, and fills in the gaps – what he was feeling, seeing, doing, behind the scenes. What actually happened, as opposed to what was reported. This does not take away from the integrity of the original report but bolsters it in terms of completeness; they are now deeper, richer stories. Possibly “truer”.

Penguin Random House

Leigh Sales does this “between the lines” of the individual narratives in her latest (and third) book Any Ordinary Day: Blindsides, resilience and what happens after the worst day of your life.

Sales recounts the stories of seven ordinary Australians whose lives, in a heartbeat, became extraordinary and visible through traumatic incident; Stuart Diver, Louisa Hope, Walter Mikac, Hannah Richell, Michael Spence, James Scott and Juliet Darling.

What makes this book so valuable is that she interweaves discussion of some of her more dubious decision-making processes as a journalist, recognising the depth of her questionable actions. This is courageous writing, particularly from such a high profile professional.

But rather than framing Sales as untrustworthy, her self-effacement pertaining to ethical breaches helps us to see how decisions are made in the field, in the heat of reporting. How mistakes are made, in the name of getting the “story”. She writes shamefully of some of these decisions, but not necessarily regretfully; all were made as part of her own learning curve, manifesting as the skilled anchor we turn to nightly on our screens.

Read more:

Journalism needs to practice transparency in a different way to rebuild credibility

David Moir/AAP

The power of disclosure

Sales’s book performs as part memoir/part trauma narrative/s/part investigation/part meta; and it is on page 99 that she begins her craft mea culpa. She writes:

When I look back at the mistakes I’ve made as a reporter including experiences that to this day make me feel ashamed, I can see that they were usually due to a failure of empathy […]

Authentic empathic journalistic disclosure is a means to garner more public trust, potentially portraying journalists as robust yet feeling professionals; as mortals with flaws; as fallible, but with a genuine belief in the integrity of their mission – informing the people, for the people.

Shining from the pages of Sales’ text is a self-effacing honesty, rarely accessed, around this type of journalistic thinking, craft and process. Included is not just a discussion of empathy, but demonstration of embodied empathic, on-the-ground interviewing.

The text is framed by trauma. Sales begins this hybrid narrative with her own: the breath-taking story of her near-death experience in 2014, during the emergency delivery of her second child; not only her near-death, but that of her tiny son, as well; and with his survival, the lingering probability of brain damage.

Michael Reynolds/AAP

She then launches into well-formed and intimate discussions with the seven people whose stories form the basis of the book. This is Sales’ attempt at dealing with her own brush with death; a gathering of tales about resilience, fears and vulnerability.

The dominant craft on display here is her interviewing skills, and her ability to elicit authentic responses from her subjects. She writes:

I know how to craft a good line of questioning that helps [people] open up. I’m a strong listener and I follow up what people are saying.

These are the two most essential techniques a young journalist or writer can acquire – crafting the right questions and listening – and it takes practise and time to develop and evolve.

Intimate narration

What Sales also does supremely well is narrate – intimately and closely, as if she is whispering in your ear. She begins the text with second person point of view (you), unusual from a journalist and difficult to sustain.

But she gets away with it as it helps convey her main theme – ordinary days turning extraordinary in a heartbeat – and she places us in her metaphoric shoes. She switches to singular third person narration (he); then to plural first person (we), before launching into her first person voice. This technique only works when it is apt – and it is apt here.

Daniel Boud

Her research into the neuroscience around trauma is in depth but accessible; and her quest to discover more about growth following traumatic pain is insightful and (dare I write without sounding mawkish) hopeful.

“What we see about shocking blindsides doesn’t tell us anything remotely like the whole story,” she writes. “Being struck by something awful is not the end of every good part of life”. For everyone, this is knowledge worth having.

The final chapter bookends the text with more of Sales’ own story – the breakdown of her marriage (succinctly and unsentimentally narrated) and an undiagnosed illness of her eldest son (we also learn that her youngest son has shown no sign of damage from his birth ordeal).

Teaching empathy

Sales tells us of callow mistakes made starting out as a journalist. It is with this hindsight and insight – a glimpse behind the maturing practice – where we sense both her ambition and elation for her assignments. Some she executes well, sometimes fluking it; in undertaking others, she clearly believes she made unethical choices.

But she does not lend herself the freedom of simply hiding behind youth, as she writes: “ … sadly, I can identify similar mistakes when I was a senior reporter”. It is in the candid telling of these fraught back stories that the humanity of Sales is made whole.

Not just the resolute grip of the interviewer on 7.30; nor fellow journalist Annabel Crabb’s best friend – clever, funny, playful – on their podcast Chat 10 Looks 3. But the woman, in love with story and storytelling, growing into her profession.

It is easy to write that empathy must be taught to our young journalists and writers; that it may be the key to subverting the disparaging distrust the public embraces towards industry.

But how to “teach” empathy? It has to be a discussion framed by ethics – the almighty notion of swapping shoes and walking in them. Stopping in the field, just stopping for a moment, and thinking about the person or story you are pursuing. Feeling what it must feel like to be them.

Read more:

Do art and literature cultivate empathy?

Now we have an idiosyncratically Australian text, written by one of the most respected Australian journalists, to teach with; one that expounds honesty about poor ethical choices, and evidence of embodied empathic interviewing. Sales’ deep enmeshing with her interviewees does not undermine the rigour of her interrogation – she still asks the hard questions and mines deeply – and the interviewees always answer, with grace.

We hear and read the back and forth of the interview with her subjects; her reflections and asides set out in print. Would she be asking these questions in this way, if she had not suffered her own cataclysmic trauma with the birth of her second son? Perhaps – I think she was getting there.

Robert Forsaith/AAP

Sales writes of the end of that year, 2014, and broadcasting the coverage of two incidents that vibrated throughout the nation, binding us collectively in their thrall: the public death of cricketer Phillip Hughes and the Lindt Cafe siege in Sydney.

It was all getting a little too much, on the back of her son’s traumatic birth. There was just too much palpable pain adrift, and she no longer felt safe. So she imagined this book, and by using the tools of her trade, she interviewed and wrote until it was done.

Perhaps it is journalistic therapy – conceptually, it definitely began that way, Sales admits. She was looking to write her way out of aggregated pain and sorrow. But I believe the denouement of this text is her greatest gift – the demonstration of empathy not as antithesis to good story re-telling, but as integral.![]()

Sue Joseph, Senior Lecturer, Writing and Journalism, FASS, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Finished Reading: The Catalpa Rescue – The Gripping Story of the Most Dramatic and Successful Prison Break in Australian History by Peter FitzSimons

David Gillespie’s ‘Teen Brain’: a valid argument let down by selective science and over-the-top claims

from shutterstock.com

Sarah Loughran, University of Wollongong

Screen time has arguably become the most concerning aspect of development for modern-day parents. A 2015 poll identified children’s excessive screen time as the number one concern for parents, overtaking more traditional concerns such as obesity and not getting enough physical activity.

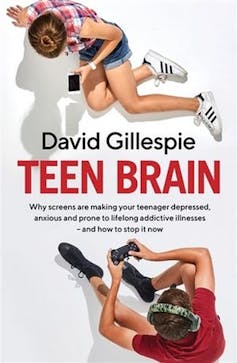

This is the issue explored in David Gillespie’s new book, Teen Brain. The tagline explains that the book delves into

why screens are making your teenager depressed, anxious, and prone to lifelong addictive illnesses – and how to stop it now.

This provides some idea of the emotive and provocative way the book’s content is delivered.

Given smartphones and tablets are everywhere, a message on limiting their use could not be more timely. The Australian government recently released guidelines recommending a maximum two hours per day of recreational sedentary screen time for teens.

It also recommended parents establish consistent boundaries around the duration, content and quality of such screen use.

Read more:

Eight things that should be included in screen guidelines for students

However, Gillespie has missed an important opportunity to communicate this with his book. In the introduction Gillespie says he’s “made some pretty outrageous claims” but they will all be backed up by solid science. He delivers on the first part, but too often the solid science is lacking.

Pan Macmillan

Dodgy science

After what can only be described as a controversial introduction – in which puberty is referred to as a period when all “males turn into large, hairy, smelly beasts with no impulse control and a desire for danger and sex” – Gillespie attempts to explain some basics of the workings of the human brain.

But this explanation is simplified and selective, which is problematic because it is then used as a basis for many of the arguments throughout the book. And the brain, and associated human behaviour, is far more complex than Gillespie’s seeming understanding.

The second section largely focuses on teen issues intertwined with parenting tips, with reference back to the brain basics. This information is aimed at managing, and ultimately avoiding, negative outcomes in teens – such as risk-taking behaviours, addiction and adverse mental-health issues.

According to Gillespie, such consequences are largely attributable to screen-based electronic devices.

This section contains statements that aren’t referenced at all, such as:

the stimulant effect of caffeine is identical to the stimulant effect of the dopamine-stimulating apps installed on your child’s device

Those that are – such as those under the heading “Teen depression and anxiety are on the rise” – often have selective references that fit the author’s narrative rather than reflecting the current state of the science.

In regards to anxiety, the book only presented parts of the research paper that it noted suggested anxiety had alarmingly tripled between 2003 and 2011. What had tripled were the presentations of anxiety symptoms. The overall diagnosis of anxiety actually remained stable.

The paper’s authors themselves state that what the results mean remains unclear. They could reflect a genuine increase in anxiety, but could also be attributed to an increased awareness by GPs or increased help-seeking behaviour of teens.

Then there are statements that are actually just plain wrong. For instance, Gillespie suggests

something else must lie at the heart of the epidemic of teen anxiety and depression, and there’s good evidence that this something is being home-delivered by the modern equivalent of a textbook – the tablet device.

Not surprisingly, this so-called “good evidence” is not provided.

In several places throughout the book, Gillespie links smartphones and electronic devices with dramatic decreases in teen pregnancy, alcohol consumption, illicit drugs and violent crime.

from shutterstock.com

While it’s true there have been declines in teen pregnancy, substance use, and crime, this is not necessarily true for all countries.

For example, a recent study showed although substance use, unprotected sex, crime, and hazardous driving were reducing in US adolescents, the same trends did not apply consistently across other developed countries.

And although the study noted smartphones and social media were one possibility behind these declines, the way in which they might do this, and if in fact they actually do, is yet to be investigated.

Read more:

Australian teens doing well, but some still at high risk of suicide and self-harm

Declines in risk-taking and addictive behaviours in teens can only be seen as a good thing, but Gillespie manages to use this to fit his narrative. That is, that smartphones and electronic devices are indeed responsible for these positive changes, but at a cost.

That cost is that the use of such devices is replacing these teen problems with a whole set of new ones: dramatic increases in teen anxiety, depression, self-harm and suicide. But again, this is done with the use of misleading, or completely absent, evidence.

Teenagers aren’t all the same

Gillespie presents a one-size-fits-all kind of approach throughout his book, which is also problematic, because not all teenagers are the same. There are large differences among individuals and how they are able to manage things such as anxiety, drug or alcohol use.

Genetics, as well as our environment, influence our behaviour. So what may work for one teenager, may not necessarily work for another.

The book places a large emphasis on the role hormones play in our reward pathways and addiction. One example is oxytocin. Gillespie says that “teenagers are uniquely susceptible to the power of oxytocin” and that “adolescence is a phase when the addictive power of oxytocin is magnified enormously”.

But there are substantial differences in oxytocin levels between individuals, and how each person’s system reacts to these, which the book completely ignores.

Read more:

How childhood trauma changes our hormones, and thus our mental health, into adulthood

The book culminates with five key points for how parents should “harden up to save their kids”. These include parents making the rules, and breaches of the rules being punished consistently.

Gillespie also advises that “all teens need eight hours’ sleep a night”. This recommendation falls outside the amount of sleep those under 14 years old need (9-11 hours for 5-13 year olds), and only represents the bare minimum recommended for those 14 years and older (8-11 hours for those aged 14-17).

The real shame overall is that the key message, that we should limit our teens’ screen time, is actually a good one. Although research remains scarce, there are some initial reports suggesting excessive screen use may have an impact on teens’ well-being, particularly sleep, anxiety and depression.

But Gillespie has reported it all in a way that is grossly over the top and overstated, and at times incorrect or just plain offensive.

This kind of communication only serves to perpetuate fear and create anxiety – the exact things that the author claims his book will fix.![]()

Sarah Loughran, Research Fellow, University of Wollongong

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.