Wits University Press

Desiree Lewis, University of the Western Cape and Gabeba Baderoon, Penn State

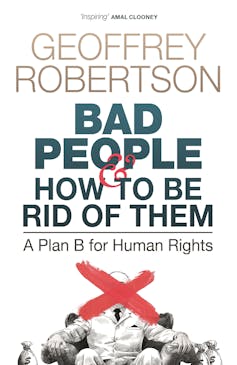

In the third decade of the new millennium, despite many publishers still seeing black women’s writing as having a limited market, readers have far more access than before to publications by writers from the global South. In particular, the perspectives of black women are certainly more visible in the public domain.

Yet gaps and erasures – based on intellectual authority, financial resources and visibility in the knowledge commons – mean that it’s still easier for work by black, postcolonial and decolonial feminists from global centres to secure publication and wide distribution.

As a result, the growing audience of radical young readers grappling with questions about race, gender, sexuality and freedom in global peripheries often have to turn to critical writing outside their national contexts, which inflect the topics they want to explore. Even for many restless and radical readers in the global North, much remains silenced and absent.

Wits University Press

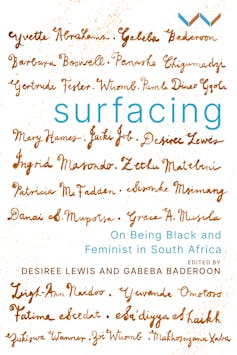

In the new book Surfacing: On Being Black and Feminist in South Africa, South African author Zukiswa Wanner has contributed a piece titled Do I Make You Uncomfortable? about writing in a white publishing industry.

It reminds us that black women writers in South Africa have distinct experiences of being stereotyped. Wanner sums this up in her confrontation with one reviewer who described her work as “chick lit”.

And if black women are the majority in South Africa and I am therefore the standard, shouldn’t it just be called a good book? And I was chick lit versus what? Could she point out to me the male authors in South Africa whose books she’d referred to as ‘cock lit’? Take (JM) Coetzee, with his women characters who aren’t well-rounded and don’t seem to have any agency; was he cock lit?

Undocumented and innovative

Surfacing traces a path within black South African feminist thought in 20 dazzling chapters. The collection shows how radical black South African women have been part of several traditions of undocumented intellectual and artistic legacies. In the book Mary Hames recalls, for example, the radical spaces outside conventional classrooms in which she studied banned material during the anti-apartheid struggle.

Our aim as editors was to show how writers in the academy, fiction-writing, journalism and the art world are grappling innovatively with essential topics. Like the politics of self, the complexities of sexual freedoms and identities beyond the blunt frameworks of human rights models. And how to think about “knowledge” more completely and adventurously.

The rich descriptions and interpretations of local realities in Surfacing refine the categories of transnational and black feminism. They bring the breadth of black feminist engagement in the south of the continent into fuller view.

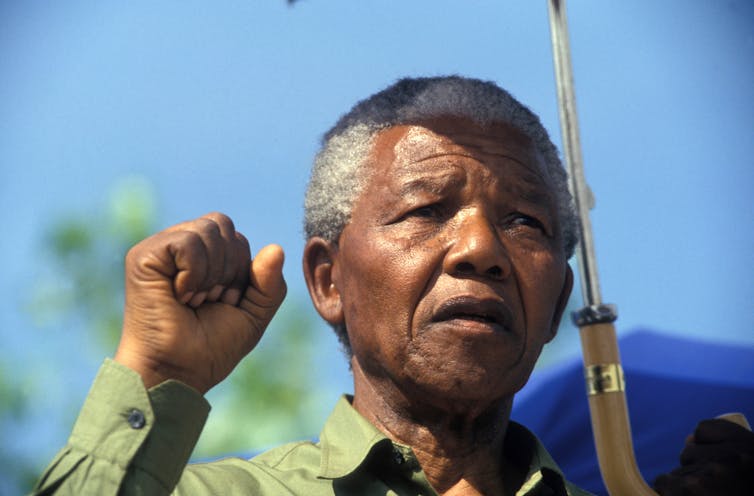

Sara Baartman and Winnie Mandela

The book is acutely aware of the contrast between the absence of acknowledgement of most black South African women writers and the way certain women, like Khoi historical figure Sara Baartman and activist and politician Winnie Mandela, have been made into global icons. It therefore starts with reflections on them.

Sara Baartman has been exhaustively examined in the north and Winnie Mandela has been the subject of numerous biographical, fictional and non-fictional projects by white scholars.

Intervening into this legacy, author Sisonke Msimang writes an emphatically self-reflexive study which reframes Winnie Mandela. Yet in doing so her interest “was never about ‘cleaning up’ her image or revising facts. It was about recognising that the facts about her required contextualisation.”

Most publications by black South African women are seen as testimonial or fictional. But the contributors of Surfacing seek both to contribute to and to interpret existing bodies of knowledge. In addition, the collection will undoubtedly be remembered for its enthralling writing.

New narratives

Many chapters take the elastic form of the personal essay. For example, academic and poet Danai S. Mupotsa draws on poetry to talk about experiences of both intimate and public scale. Academic and author Pumla Dineo Gqola pens a playfully serious letter to the South African artist Gabrielle Goliath. And photographer and curator Ingrid Masondo collaboratively authors an essay with the photographers about whom she writes.

In other pieces, academic and author Barbara Boswell recounts her fascinating exchanges with feminist student activists during the #RhodesMustFall protests in her essay about the meanings of pioneering feminist author Miriam Tlali for the present. Academic Grace Musila’s delightful My Two Husbands unfurls the experience of being a brilliant student whose intellectual accomplishment was seen by some men as undermining theirs. Yet within her family her education constituted a cherished and defining achievement.

Read more:

Rest in power, Miriam Tlali: author, enemy of apartheid and feminist

Several chapters in the collection trace the intersections of religion and feminist thinking in South Africa. Academics Sa’diyya Shaikh and Fatima Seedat offer vivid reflections as Muslim feminists on the costs of feminist neglect of the gender of divinity. Dancer, choreographer and academic jackï job’s striking memoir traces a shift from Christian expectations of how to be a “lady” to finding a language in dance for becoming “more than just this body”. And scholar and activist gertrude fester-wicomb recounts her experience as a Christian lesbian anti-apartheid activist of the constrained spaces for queerness during the 1980s.

How to recover histories in the face of reticence is evocatively described by essayist and novelist Panashe Chigumadzi. Through patient listening, she discovers how to hear the language of her grandmother’s silences. In The Music of My Orgasm, anthologist, essayist and poet Makhosazana Xaba movingly testifies to the heritage of feminism she received from her grandfather and her mother. She describes how she learned to cultivate the pleasures of her own body as a force of radical sexual and political liberation.

In their tender relationship to the land on which they grow organic food and medicine, historian and farmer Yvette Abrahams and sociologist and activist Patricia McFadden’s chapters map a visionary future of sharing and abundance.

Why these writings matter

Throughout the book, it is therefore made clear that foregrounding the positionality of the writer – the social and political contexts that shape their identities – can deepen what is being said.

Who the author is and what perspective she speaks from are in fact integral to her view of the world.

Contrary to advocates of “universality” and “detachment”, this stance seeks to strengthen growing efforts to “surface” the rich diversity of ways of seeing and understanding our world.

Surfacing: On Being Black and Feminist in South Africa is available from Wits University Press![]()

Desiree Lewis, Professor of Gender Studies, University of the Western Cape and Gabeba Baderoon, Associate Professor of Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies and African Studies, Penn State

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.