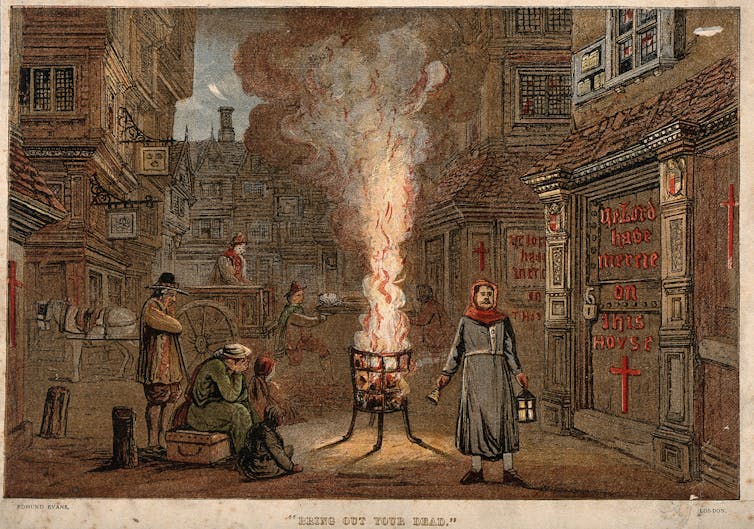

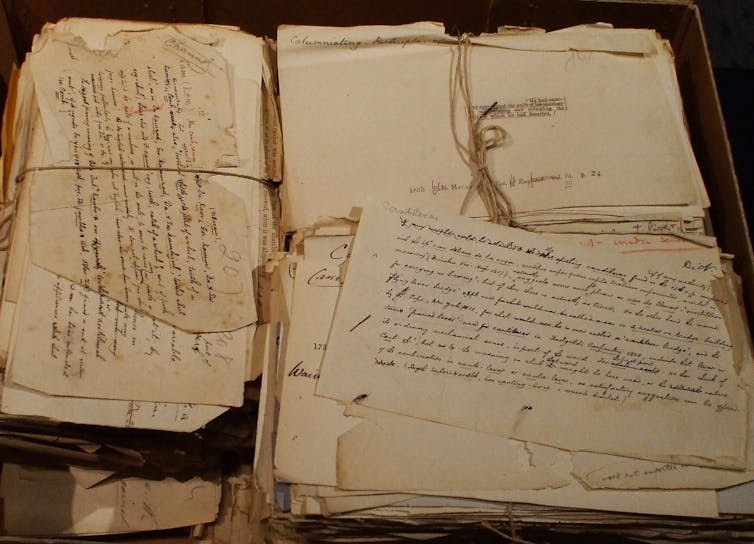

Wellcome Images, CC BY-NC-SA

David Roberts, Birmingham City University

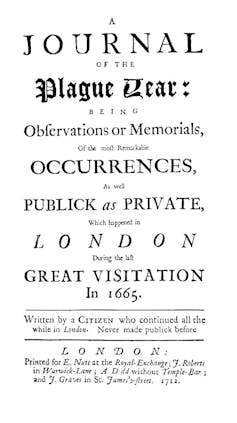

In 1722, Daniel Defoe pulled off one of the great literary hoaxes of all time. A Journal of the Plague Year, he called his latest book. The title page promises “Observations of the most remarkable occurrences” during the Great Plague of 1665, and claims it was “written by a citizen who continued all the while” in London – Defoe’s own name is nowhere to be found.

It was 60 years before anyone twigged. From oral testimonies, mortality bills, lord mayor’s proclamations, medical books and literature inspired by the 1603 plague, Defoe had cooked the whole thing up.

National Maritime Museum, London.

And yet this extraordinary book lies like the truth. It’s the most harrowing account of an epidemic ever published – and it really leaps off the page now in the era of COVID-19. We feel what it was like to walk up a main thoroughfare with no one else about. We read of the containment orders published by the government, and how people got round them. We share the distress of families denied proper funerals for their loved ones.

We learn of the mass panic as people tried to understand where the disease came from, how it was transmitted, how it could be avoided, what chance you had if you caught it, and – most modern of all – how fake news and fake practitioners multiplied answers to all those questions.

Then and now

Bubonic plague was, of course, far nastier than coronavirus. In its ordinary form – transmitted by fleabites – it was around 75% fatal, while in its lung-to-lung form, that figure went up to 95%. But in the way it was managed – and the effect it had on people’s emotions and behaviour – there are eerie similarities amid the differences. Defoe captured them all.

His narrator, identified only as HF, is fascinated by what happened after the lord mayor ordered victims to be locked in their homes. Watchmen were posted outside front doors. They could be sent on errands to fetch food or medicine and took the keys with them, so people contrived to get more keys cut. Some watchmen were bribed, assaulted or murdered. Defoe describes one who was “blown up” with gunpowder.

HF becomes obsessed with the weekly mortality figures. They charted deaths by parish, giving a picture of how the plague was moving around the city. Still, it was impossible to be sure who had died directly of the disease, just as in the BBC news today we hear people have died “with” rather than “of” COVID-19. Reporting was difficult, partly because people were reluctant to admit there was an infection in the family. After all, they might be locked in their homes to catch the disease and die.

HF is appalled by those who opened up taverns and spent their days and nights drinking, mocking anyone who objected. At one point he confronts a group of rowdies and gets a torrent of abuse in return. Later, exhibiting one of his less appealing traits, he is gratified to hear that they all caught the plague and died.

He is a devout Christian, but the stories that worry him most are the ones that still shock everyone today, regardless of their beliefs. Is it possible, he asks, that there are some people so wicked that they deliberately infect others? He just can’t square the idea with his more kindly view of human nature. Yet he hears plenty of stories about victims breathing into the faces of passers by, or infected men randomly hugging and kissing women in the street.

Discriminating disease

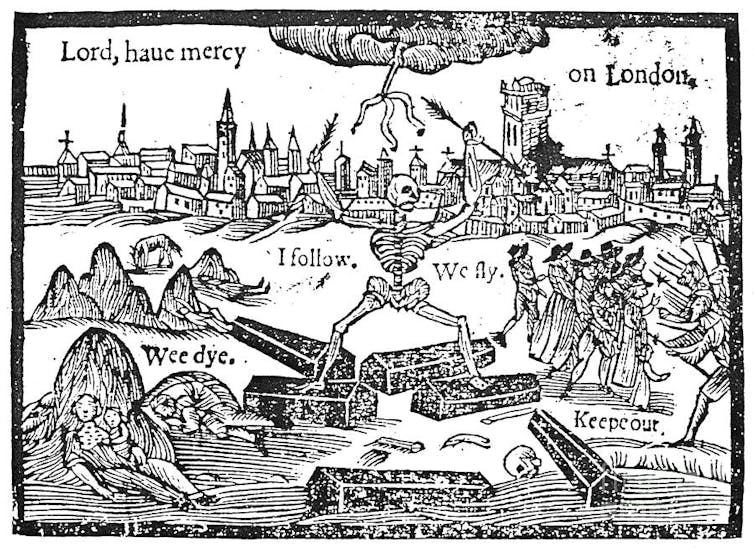

When Prince Charles and Boris Johnson fell ill recently, we were told the virus “does not discriminate”. HF has something to say about that. For all his uncertainties, he is adamant about one thing. Plague affected the poor disproportionately. They lived, as they do now, in more cramped conditions, and were more susceptible to taking bad advice.

They were more likely to suffer ill health in the first place, as now, and they had no means of escape. Near the start of the outbreak in 1665, the court and those with money or homes in the country fled London in droves. By the time the idea had occurred to the rest of the population, you couldn’t find a horse for love or money.

Contemporary English woodcut on the Great Plague of 1665.

Throughout the journal, HF tells us he hopes his experiences and advice might be useful to us. There’s one thing in particular governments might learn from the book – and it’s tough. The most dangerous time, he reports, was when people thought it was safe to go out. That was when the plague flared up all over again.

Plague literature is a genre in its own right. So what draws writers and readers to such a grisly subject? Something not entirely wholesome, perhaps. For writers, it’s the chance to explore a world in which fantasy and reality have swapped places. We depend on the writer as heroic narrator, charting the horror like the best news reporter.

For readers, it’s the feeling that you might sneak with him to the very edge of the plague pit and live to tell the tale. For his closing words, HF hands us a doggerel poem that sums up his feelings and ours:

A dreadful plague in London was

In the year sixty five,

Which swept an hundred thousand souls

Away: yet I alive!

David Roberts, Professor of English and National Teaching Fellow, Birmingham City University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.