Kaeten Mistry, University of East Anglia

Former US national security adviser John Bolton is the latest ex-government official to rebuke the misconduct, ignorance and self-serving behaviour of the president, Donald Trump, in the form of a tell-all book. The Room Where It Happened details Trump’s idiosyncrasies, offers of favours to authoritarian leaders, lack of basic knowledge, and “obstruction of justice as a way of life”.

Promoting the book in a series of interviews, Bolton told one reporter that he hopes it will be a one-term presidency: “Two terms, I’m more troubled about,” he said.

Yet the battle around the publication is more than another Trumpian political scandal. It centres on the disclosure of US national security information, particularly the concept of “prior restraint” that allows the government to censor speech or expression before it has occurred.

The issues originate in whistleblowing in the 1970s when former officials spoke out against government wrongdoing. Bolton is certainly no whistleblower although the legacy of that era informs an ongoing struggle today around first amendment freedom of speech rights and state secrecy.

Beyond politics

In many respects, the case is emblematic of Trump’s White House. Bolton was in post from April 2018 to September 2019, the longest serving national security adviser under Trump, but now asserts the president “lacks the competence to carry out the job” and is not “fit for office.” When the first excerpts from the book emerged, Trump characteristically lashed out with a tweet full of insults and accusations.

The politics are certainly messy. Bolton, a hawkish Republican, is an opportunistic political operative. With publication of the book, he has angered Trump’s supporters. At the same time his revelations have not won him friends among the president’s numerous opponents.

Bolton’s refusal to testify during the impeachment hearings at the beginning of the year, preferring to save his material for his book, has led to accusations that he was putting personal interest before national interest as well as profiteering, and trying to save his legacy.

Prior restraint

The crux of the matter is not individual politics but whether Bolton was authorised to publish the memoir. On June 20, Judge Royce C Lamberth of the Federal District Court of the District of Columbia denied a last-ditch Justice Department motion to block its release. Noting that excerpts were already printed and the book widely in circulation, he stated that: the “the damage is done. There is no restoring the status quo.”

The author nonetheless remains in trouble. The judge concluded that: “Bolton has gambled with the national security of the United States” by potentially exposing secrets. The government could still sue Bolton for not following the prepublication review process that applies to everyone who signs a secrecy agreement.

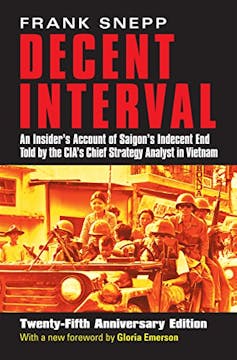

The prepublication review system was created following a wave of whistleblowing that exposed government abuse in the 1970s. The most famous example was Daniel Ellsberg’s revelation of the Pentagon Papers, a top secret military report on US involvement in the Vietnam War. Other whistleblowers including Frank Snepp, Philip Agee, and Victor Marchetti wrote books detailing their experiences working for the Central Intelligence Agency. Not all of them revealed secrets but the fact they were speaking publicly raised concerns.

In response, the US government created a process requiring all current and former national security officials to submit material intended for a public audience before it could be published. This vetting process was intended to protect classified information.

The system has been riddled with problems from the beginning, including lengthy review processes and arbitrary decision-making around what can and cannot be published. The issues have afflicted both works that criticise and support US foreign relations. In 2019 the Knight First Amendment Institute and the American Civil Liberties Union filed a lawsuit challenging the system as dysfunctional and placing too much power in the hands of reviewers.

Amazon

Authors who refuse to submit work for prepublication review are liable to be prosecuted. After publishing a 1977 book without approval, Snepp was ordered by the Supreme Court to forfeit all royalties to his former employer, the CIA. The court ruled that the book had caused “irreparable harm” to national security.

Bolton’s legal team claims he did not violate the secrecy agreement because he had satisfied all issues raised by the National Security Council’s senior director for prepublication review.

But the nature of the secrecy system and the review process is nebulous and allows the executive branch significant room for manoeuvre. While Trump’s assertion that “every conversation with me… [is] highly classified” is a stretch, the suggestion that “Bolton broke the law” and “must pay a very big price for this, as others have before him” is consistent with the broad authority afforded to presidents on national security matters.

The White House recently opened a second prepublication review process of Bolton’s book. The outcome of this latest review, which will be overseen by Judge Lambert, will determine his fate. If the courts follow historical precedent and rule in favour of the government, like Snepp before him, Bolton stands to forfeit his reported $2 million advance, and could face criminal liability that includes the possibility of a jail sentence.

Speech rights

While the author remains in legal peril, Bolton’s revelations continue to receive widespread attention. That the press can report national security secrets is rooted in another seminal whistleblowing case, Ellsberg’s release of the Pentagon Papers to the New York Times and other outlets. The Supreme Court ruled that prior restraint of the press was unconstitutional.

The First Amendment of the US constitution protects freedom of speech and freedom of the press from government interference. But when it comes to discussing national security information, the press enjoys greater protection than government employees.

In hyper-partisan times, it can be hard to look beyond the immediate political stakes. Yet the issues raised by this episode predate Bolton and Trump and are likely to persist long after them.![]()

Kaeten Mistry, Senior Lecturer in American History, University of East Anglia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.