StudioCanal

Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden has been described as “the most significant children’s book of the 20th century.”

First published in 1911, after being serialised in The American Magazine, it was dismissed by one critic at the time as simple and lacking “plenty of excitement”. The novel is, in fact, a sensitive and complex story, which explores how a relationship with nature can foster our emotional and physical well-being. It also reveals anxieties about national identity at a time of the British Empire, drawing on ideas of Christian Science.

The Secret Garden has been read by generations, remains a fixture on children’s publishing lists today and has inspired several film versions. A new film, starring Colin Firth, Dixie Egerickx and Amir Wilson, updates the story in some ways for modern audiences.

Studiocanal

The book opens as nine-year-old Mary Lennox is discovered abandoned in an Indian bungalow following her parents’ deaths during a cholera outbreak. Burnett depicts India as a site of permissive behaviour, illness and lassitude:

[Mary’s] hair was yellow, and her face was yellow because she had been born in India and had always been ill in one way or another.

Mary is “disagreeable”, “contrary”, “selfish” and “cross”. She makes futile attempts at gardening, planting hibiscus blossoms into mounds of earth. The Ayah tasked with caring for Mary and the other “native servants … always obeyed Mary and gave her her own way in everything.”

On the death of her parents, Mary is sent to live with her reclusive uncle Archibald Craven at Misselthwaite Manor in Yorkshire.

Mary’s arrival in England proves a shock. The “blunt frankness” of the Yorkshire servants – in contrast to those in India – checks her behaviour. Martha Sowerby, an outspoken young housemaid, presents Mary with a skipping rope: Yorkshire good sense triumphing over Mary’s imperial malaise.

Also in the manor is Colin, her 10-year-old cousin. Hidden from Mary, she discovers him after hearing his cries at night.

Colin is unable to walk and believes he will not live to reach adulthood. Sequestered in his bedroom, Colin terrorises his servants with his tantrums: he performs “hysterics” in the model of Gothic femininity.

Transformation

Perhaps the most famous image associated with Burnett’s text is the locked door leading to the eponymous garden.

Houghton Library, Harvard University

This walled garden had formerly belonged to Colin’s mother, Lilias Craven. When she died after an accident in the garden, her husband, Archibald, locked the door and buried the key.

After Mary unearths the key, she begins to work in this mysterious, overgrown garden along with Martha’s brother, Dickon. Eventually, she manages to draw Colin out of his room with the help of Dickon, and the garden helps him to recover his strength.

Burnett draws upon the cultural connection between childhood and nature, highlighting Edwardian beliefs about the importance of the garden. Like other Edwardian texts, such as Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows (1908) and J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens (1906), The Secret Garden also explores an English turn-of-the-century interest in paganism and the occult, expressed through the book’s fascination with the Greek god Pan.

Dickon, who shares an affinity with animals and the natural world, is first introduced as he sits under a tree “playing on a rough wooden pipe” reminiscent of Pan’s flute.

IMDB/Studiocanal

Mary and Colin are both physically and psychically transformed through working in the garden. The stifling rooms and constricting passages of Misselthwaite Manor are contrasted to the freedom of the secret garden.

At first it seemed that green things would never cease pushing their way through the earth, in the grass, in the beds, even in the crevices of the walls. Then the green things began to show buds and the buds began to unfurl and show colour, every shade of blue, every shade of purple, every tint and hue of crimson.

Read more:

B&Bs for birds and bees: transform your garden or balcony into a wildlife haven

The children are healed by gardening in the “fresh wind from the moor”. Both gain weight and strength and lose their pallor. Colin’s gardening suggests mastery of the space as he plants a rose – the floral emblem of England.

Mary is subordinated as Colin’s healing becomes the text’s main focus; Colin gains the ability to walk and – importantly – to win a race against her.

Warner Bros

‘Just mere thoughts’

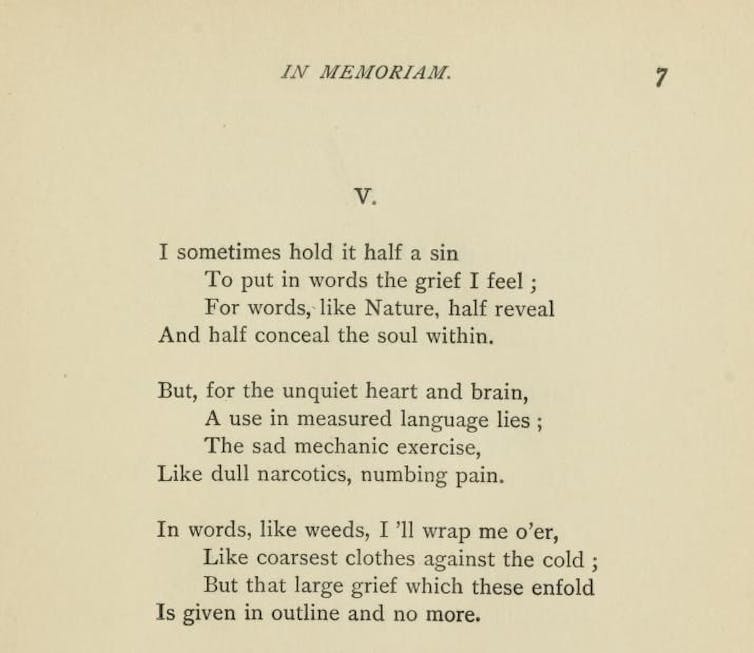

The Secret Garden emphasises the power of positive thinking: “thoughts – just mere thoughts – are as powerful as electric batteries – as good for one as sunlight is, or as bad for one as poison”.

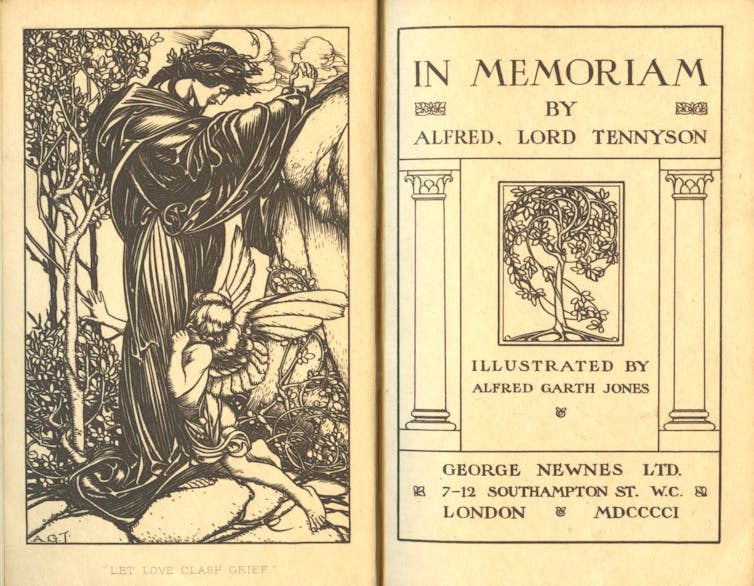

This focus on the power of positive thoughts highlights Burnett’s interest in New Thought and Christian Science. New Thought teaches that people can enhance their lives by altering their thought patterns. It was developed by Phineas Parkhurst Quimby in the 19th century, and one of Quimby’s students was Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of Christian Science. While Burnett did not join either religion, she acknowledged that they influenced her work. Both religions often reject mainstream medicine.

Read more:

Why you should know about the New Thought movement

IMDB/MGM

Belief in the healing power of thoughts is reflected as Colin chants about the “magic” of the garden.

The sun is shining – the sun is shining. That is the Magic. The flowers are growing – the roots are stirring. That is the Magic. Being alive is the Magic – being strong is the Magic. The Magic is in me… It’s in every one of us.

The Secret Garden today

Written in a time of British imperial expansion, The Secret Garden’s anxieties around national identity are evident. It draws implicit (and explicit) distinctions between the sickliness and languor of India, and the health and vitality associated with life on the Yorkshire moors.

Yet The Secret Garden still resonates with contemporary audiences. This new adaptation elaborates upon the “magic” associated with the healing power of thoughts, introducing a fantastic element to the story as Mary, Colin and Dickon enter a secret garden filled with otherworldly plants.

Director Marc Munden’s new adaptation also appears to revisit the colonialist emphasis of Burnett’s text. The adaptation shifts the time period during which the film is set to 1947, the year of the Partition of India.

This temporal change suggests an alteration to the original text’s ideas about national identity. While Burnett’s 1911 text considered Britain’s relationship with India at the height of British imperialism, Munden’s adaptation situates the narrative in the period of India gaining independence from Britain.

This new film suggests a desire to ensure The Secret Garden’s continued relevance to today’s audiences, who may be attuned to the book’s colonialist ideologies.

The Secret Garden opens in select cinemas today.![]()

Emma Hayes, Academic, School of Communication and Creative Arts, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.