Morphart Creation/Shutterstock

Stephen Rigby, University of Manchester

The sharp fall in population caused by the waves of plague which followed the arrival of the Black Death in 1348 led to one of the most dramatic periods of economic and social change in English history. By 1377, the population was around only a half of its pre-plague level but for those who survived there were new opportunities.

With a great deal of land now available, peasants could obtain larger holdings and rent them on more favourable terms. Likewise, those who worked for wages could take advantage of the labour shortage to obtain higher wages enjoy more varied diets – with more meat and dairy – and buy a wider range of manufactured goods.

The second half of the 14th century was thus a period of rising living standards, social mobility and increasing class conflict as the lower orders now sought to obtain improved terms from their landlords and employers.

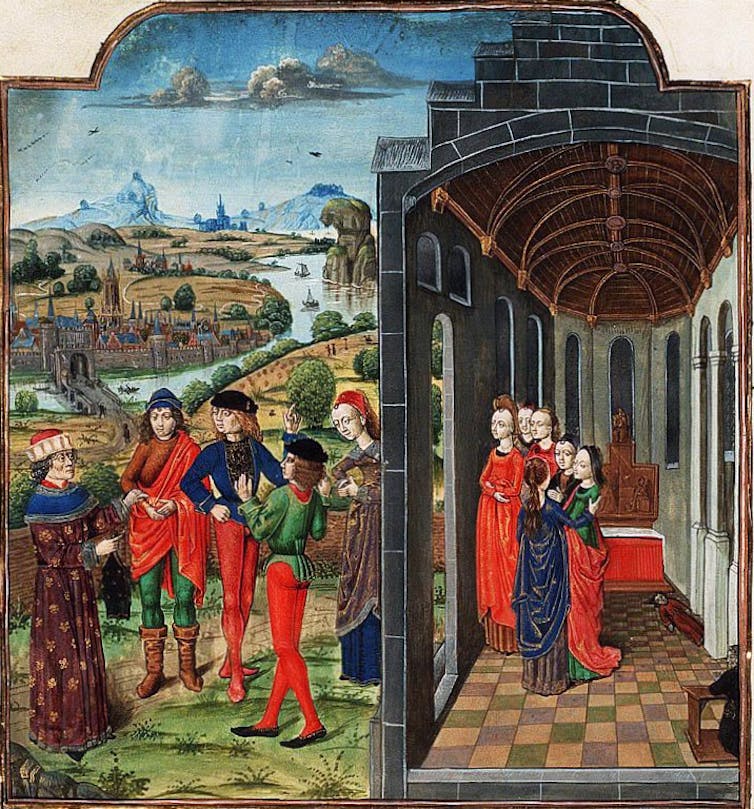

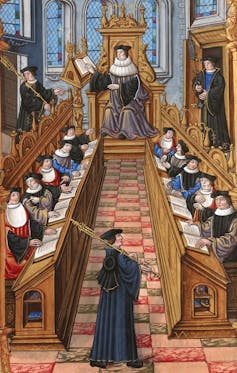

The dramatic social changes of these years drew several responses from contemporary poets. In the medieval period, imaginative literature was often seen as having an ethical function by teaching virtue, which was defined as fulfilling the expected tasks of their social order. Modern literary critics often see imaginative literature challenging dominant ideologies or providing a sanctioned space for the expression of social dissidence. By contrast, the work of poets in the post-plague era often sought to buttress the social hierarchy against the threats with which it was now confronted.

Langland and Gower against the peasants

Such sentiments are to be found in William Langland’s allegorical poem, Piers Plowman (B-version written c. 1380). Here, the poet expresses his sympathy for those who were genuinely poor or hard-working but echoes post-plague labour legislation and attacked those who, he believed, preferred to beg rather than work.

There had been frequent complaints in parliament about labourers who preferred handouts to work or who took advantage of the labour shortage to demand higher wages. In response, a series of laws were introduced to reduce labour mobility and freeze wages at their pre-plague levels. Langland also calls upon the knightly class to defend the community from those “wasters” who refused to work and criticised the labourers who impatiently demanded higher wages and refused to obey the new legislation.

Contemporary moralists complained about those who rose above their allotted station in life and so in 1363 a law was passed that specified the food and dress that were appropriate for each social class. In line with such attitudes, Langland railed against the presumption of labourers who disdained day-old vegetables, bacon and cheap ale and instead demanded fresh meat, fish and fine ale.

Berkley

Similar views are expressed in John Gower’s poem Vox Clamantis (the Voice of One Crying in the Wilderness) where the peasants are attacked for being idle and utterly wicked. The common people had fallen into an evil disposition in which they ignored the labour laws and were only willing to work if they received the highest pay.

When the lower orders refused to know their place, as in the Great Revolt of 1381 (also known as the Peasants’ Revolt), they were denounced by contemporary chroniclers as wicked, treacherous, and diabolical. In line with such criticism, Gower’s poem includes an allegorical account of the rising that portrays the rebels as farmyard animals rising up against their masters. They subsequently turn into monsters that attack humanity and becoming followers of Satan in their attachment to wrongdoing and slaughter.

Chaucer’s difficult voice

However, if Langland and Gower were openly hostile to the aspirations of the peasants and the labourers, Geoffrey Chaucer has proved more difficult to read. For many critics, Chaucer is a writer who prefers to present his readers with questions rather than providing them with stock answers. To them, his use of multiple voices and shifting perspectives pose a challenge to the accepted contemporary beliefs and exposes the kind of ideology found in the works of a Gower as partial and inadequate.

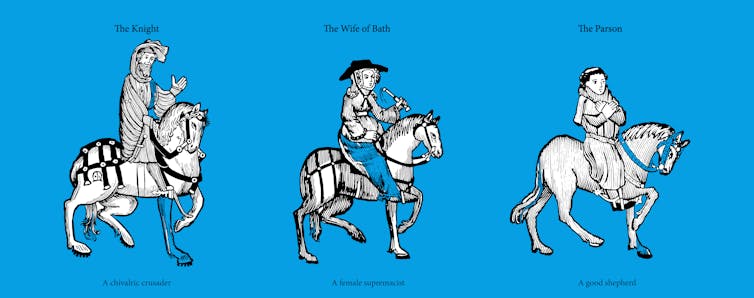

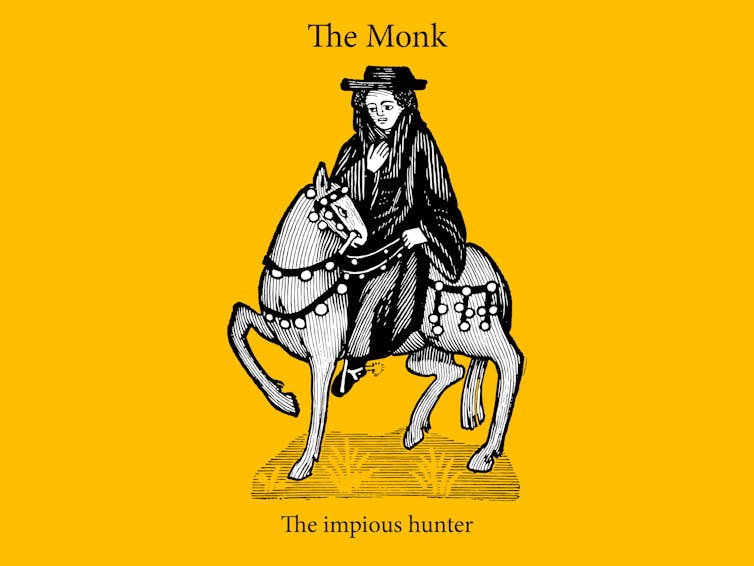

Morphart Creation/Shutterstock

Yet for other critics, Chaucer is much more conservative or even, as the medieval scholar Alcuin Blamires puts it, reactionary in his outlook. After all, among the pilgrims in the Canterbury Tales, those who are presented as admirable are the ones who dutifully perform the traditional functions of their social estate. For example, the Parson is a good shepherd to his flock, the Knight is a chivalrous crusader, and the Plowman works hard and faithfully pays his tithes. It is those who fail in their duties or seek to rise above their station whom Chaucer satirises – as when the Monk prefers hunting to a life of study and prayer or when the Wife of Bath seeks female supremacy in marriage.

Certainly, the Parson offers us a socially conservative message when, at the end of the Canterbury Tales, he preaches that as part of the divinely arranged cosmic order, God has ordained that some people should be of higher social rank and others should be lower. People should, therefore, render honour and obedience not only to God but also to their spiritual fathers and their secular superiors. Nobody should lament their misfortunes or envy the prosperity of others but rather should endure adversity in patience in the hope of obtaining joy and ease in the next life.

Given that medieval literary theory regards the ending of a text as being particularly important in conveying its meaning, we may perhaps regard Chaucer’s views as being in line with his Parson. If so, then Chaucer’s response to the social change of his day may have been rather closer to the views of Gower and Langland than many of his modern readers would like to admit.

Read and listen more from the Recovery series here.![]()

Stephen Rigby, Emeritus Professor of Medieval Social and Economic History, University of Manchester

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.