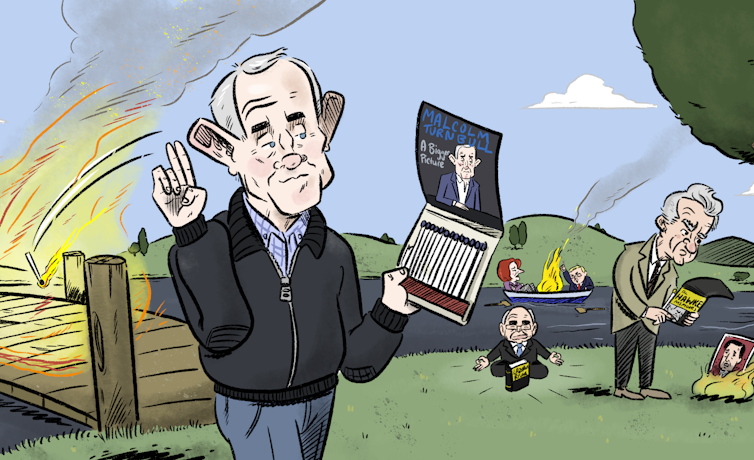

Wes Mountain/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Joshua Black, Australian National University

Landing in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic, it may seem strange former prime minister Malcolm Turnbull’s memoir has generated so much political controversy.

Turnbull has been accused of hypocrisy and championing socialism, and has been threatened with expulsion from the Liberal Party.

In A Bigger Picture, Turnbull deals candidly with his antagonists inside the Coalition, who fought him bitterly on the same-sex marriage reform and climate policy. Similarly, he names and shames those he blames for the leadership insurgency of August 2018. All of this was expected, but none of it must please the current government.

But is the book any more inflammatory than previous prime ministerial memoirs?

Political controversy is a trademark of political memoir publishing in Australia. A Bigger Picture is just another page in that story.

Until the 1960s, prime ministerial memoirs were the exception, not the rule. Between 1945 and 1990, just three former prime ministers chose to publish books about their political lives. Two of them – Billy Hughes and Robert Menzies – produced two books each, and both political veterans sought to avoid “telling tales out of school”. Both seemed more interested in foreign affairs, particularly our imperial relationship to the UK in the case of Menzies.

The dismissal of the Whitlam government provoked both Sir John Kerr and Gough Whitlam to publish their memoirs. After reading extracts of Kerr’s Matters for Judgement, Whitlam decided to “set the record straight immediately” by writing The Truth of the Matter. His second book, The Whitlam Government, was also designed to make a political splash. Promising to explain the “development and implementation” of his policy program, the book was timed for release on the tenth anniversary of the dismissal itself, ensuring maximum publicity.

Since then, political controversy has accompanied prime ministerial memoirs, in part because incumbent political parties and leaders have had a vested interest in how these books might affect their popularity.

In his 1994 political memoir, Bob Hawke accused his rival and successor, Paul Keating, of calling Australia “the arse-end of the world” during an argument about the Labor leadership. Further, Hawke accused Keating of failing to support Australia’s involvement in the Gulf War against Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990.

Keating, who was attacked in parliament in October 1994 over the claims, called both allegations “lies”. Hawke offered to take a lie-detector test to prove his sincerity. Senior ALP figures recorded their outrage at Hawke’s memoir. But Hawke hit back, describing them as “precious self-appointed guardians of proper behaviour”.

Hawke’s predecessor also damaged his relationship with his own party in the process of publishing his memoirs. Malcolm Fraser’s Political Memoirs, written with journalist Margaret Simons, was recognised as one of Australia’s top ten books of 2010. His outspokenness – in the book and in his post-prime-ministerial life more generally – earned him many attacks from Coalition MPs.

John Howard handled the politics of his memoirs better than most politicians. Though the book was antagonistic toward his former treasurer, Peter Costello, Howard promised to “deal objectively” with events and relationships in Lazarus Rising. Ever the party stalwart, Howard and his publishers re-issued the book after the 2013 election with a new chapter that touted Tony Abbott’s “high intelligence, discipline […] good people skills”.

Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard both publicly took aim at one another in their memoirs, which made for plenty of media fodder. In My Story, Gillard described Rudd’s leadership as a descent into “paralysis and misery”. Rudd returned fire, calling her book her “latest contribution to Australian fiction”. However, he was unable to dent the book’s commercial success.

Four years later, Rudd in The PM Years accused Gillard of plotting “with the faceless men” to become prime minister. In a bid to patch over the historic rifts, he subsequently promised the Labor Party’s 2018 National Conference that the “time for healing” had come.

Critics of Turnbull’s book – such as Sky News’ Andrew Bolt and 2GB’s Ben Fordham – have argued that he and his publishers, Hardie Grant, were wrong to “betray confidences” and divulge “private conversations”.

In reality, political memoirs have always pushed against conventions of political secrecy. In the 1970s, British cabinet minister Richard Crossman published his Diaries, which included detailed descriptions of how cabinet functioned. The British establishment subsequently conducted the Radcliffe review into political memoirs and diaries. It found such material should be kept secret for 15 years, but that civil servants could do little to stop their political masters from publishing.

In 1999, Australia’s Neal Blewett was warned that publishing his A Cabinet Diary, recorded seven years earlier, could lead to prosecution under the Crimes Act because it revealed confidential cabinet discussions. Calling the public service’s bluff, Blewett published anyway. He explained in the book that “a few egos will be bruised, but cabinet ministers are a robust lot”. His diary shed significant light on the trials and tribulations of a ministerial life.

Since then, countless MPs and ministers have published books that claim to accurately represent personal conversations, some based on private notes (as Costello claimed in his memoirs), others on diary entries (as is the case in Turnbull’s book). In recent years, politicians have reproduced text messages and email exchanges in their books, as Bob Carr did in his 2014 book, Diary of a Foreign Minister. In each version of history, the author is the essential policymaker.

Read more:

View from The Hill: Malcolm Turnbull gives his very on-the-record account of Scott Morrison

In his book, Turnbull reveals private conversations and WhatsApp exchanges with colleagues, world leaders, public servants and more. His accounts of cabinet discussions are hardly ground-breaking: cabinet debates about the economy and national security under the Abbott government, for instance, were thoroughly detailed in Niki Savva’s The Road to Ruin, while the acrimonious debates about energy policy, same-sex marriage and home affairs inside the Turnbull government were laid bare in David Crowe’s Venom. Similarly, Turnbull’s criticisms of News Corporation’s biased reporting have been aired elsewhere, and stop short of Rudd’s argument in The PM Years that Rupert Murdoch should be the subject of a royal commission.

Turnbull’s book is another addition to the history of incendiary political memoir publishing in Australia. Political parties and their media associates have confirmed once again that a successful parliamentary memoir requires deft political management.

Ultimately, A Bigger Picture is not the compendium of revelations that some may perceive. Instead, it is another picture of politics in which “character” and “leadership” reign supreme at the expense of all other political forces.![]()

Joshua Black, PhD Candidate, School of History, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.