The link below is to an article that looks at the decline in author income and its causes.

For more visit:

https://electricliterature.com/the-disastrous-decline-in-author-incomes-isnt-just-amazon-s-fault-c58468492b17

The link below is to an article that looks at the decline in author income and its causes.

For more visit:

https://electricliterature.com/the-disastrous-decline-in-author-incomes-isnt-just-amazon-s-fault-c58468492b17

Franz Krüger, University of the Witwatersrand

Hugh Lewin, who provided a unique voice on the South African story over many decades as militant, prisoner, journalist, author and much else, has died in Johannesburg at the age of 79.

Lewin is perhaps best known for two books that arose from his early involvement in the anti-apartheid underground. Bandiet, Seven years in a South African Prison, which has been described as a remarkable piece of prison literature, and Stones against the Mirror, published decades later, in which he describes grappling with the betrayal of the man whose testimony sent him to jail.

But his poetry, his children’s books and his work in publishing and the training of journalists and refugees leave as big a legacy. An outpouring of tributes has greeted news of his death. He has been called “an incredible writer and courageous soldier” by President Cyril Ramaphosa. and “a courageous stalwart” by Lord Peter Hain.

I first encountered him when he ran the small publishing house Baobab Books in Zimbabwe. Later I worked with him at the Institute for the Advancement of Journalism in Johannesburg, and will mainly remember his gentle humour, a sharp intellect that was never cutting, his ability to listen and his concern for others. It made him a great friend and outstanding teacher and mentor to many.

I will also remember the quiet dignity with which he dealt with his gradually failing health over the past decade, cared for by his partner Fiona Lloyd. His wit was still on clear display when I saw him just about a week before his death, despite frailty and struggling with the words that were his life – “I keep bumping against empty sentences,” he had previously said.

Lewin was born in the small town of Lydenburg in 1939 into an Anglican missionary family. He studied at Rhodes University before entering journalism at the Natal Witness in Pietermaritzburg.

He was quickly drawn into anti-apartheid politics of an increasingly radical kind, and got involved in the National Committee of Liberation, later renamed as the African Resistance Movement. This group of activists grew out of the Liberal Party and embarked on a campaign of sabotage of infrastructure targets, which it carried out between 1961 and 1964.

In July 1964, Lewin, then 24, was sentenced to jail for seven years for sabotage. He served this time in Pretoria Central prison, where he kept notes of his experiences in his Bible. After his release, he left the country on a “permanent departure permit”, to begin life as an exile in London.

Bandiet was published during this time. It manages both to provide harrowing detail of life in an apartheid jail and to use prison as a metaphor for the system as a whole. Reviewer Daniel Roux described the book as deserving, “its place in the global canon of prison writing”. Roux called it an,

understated, elegant and honest memoir that resists self-pity and self-glamorisation, and shows in careful detail what it feels like to drop out of one reality and to enter a completely different world.

Long banned in South Africa, the book was republished in 2002 as Bandiet – out of jail, including additional later material.

His family remember an additional result of the prison years: his skill at sewing, from sewing mailbags in jail. His stitching was apparently large but very neat.

During 10 years in London, he worked as a journalist and for the International Defence and Aid Fund, a support organisation for anti-apartheid causes.

Another 10 years of exile followed, this time in Zimbabwe, where he worked as publisher and wrote a series of children’s stories, the Jafta series, whose simple narratives spoke to the ordinary reality of Southern African children.

Hugh returned to South Africa in 1992 and began work at the Institute for the Advancement of Journalism, the institution founded by Allister Sparks to train journalists for the new democracy.

He served on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission before returning to the Institute for the Advancement of Journalism in 1998 as its executive director. It was during this time that he was involved in the early initiatives that led to the establishment of the journalism programme at Wits University.

But processing of the traumatic events of his youth was clearly not complete, and after retiring from the Institute for the Advancement of Journalism, he worked on the memoir that became Stones against the Mirror. Published in 2011, the book deals with a friendship that ended in betrayal. Adrian Leftwich was the man who gave his name to the security police and testified against him in court, and the book describes Lewin’s 40-year search for some kind of resolution.

South African author Nadine Gordimer wrote about the book:

There have been many accounts of life in the active struggle against the apartheid regime but this one is a fearless exploration into the deepest ground – the personal moral ambiguity of betrayal under brutal interrogation.

It won the Alan Paton Award in 2012 – one of many honours he has received.

During these later years, Lewin also continued his involvement in training, travelling to the Myanmar border to work with refugees with his partner Fiona Lloyd. However, failing health made this more and more difficult.

Lewin leaves his partner, two daughters from an earlier marriage and three grandchildren.![]()

Franz Krüger, Adjunct Professor of Journalism and Director of the Wits Radio Academy, University of the Witwatersrand

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that takes a look at dissident Chinese author Ma Jian.

For more visit:

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/14/books/ma-jian-china-dream-hong-kong-propaganda-censorship-orwell.html

Rachel Stenner, University of Sheffield and Frances Babbage, University of Sheffield

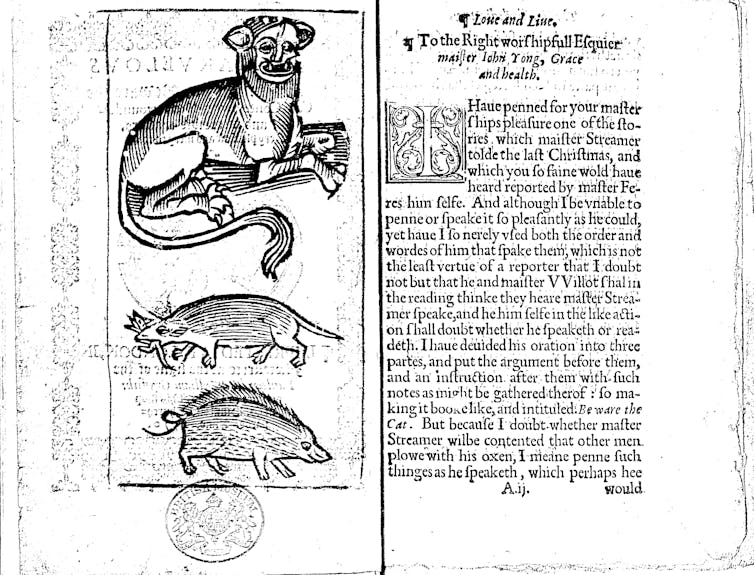

A dense work of early English prose, strewn throughout with serious and teasing marginalia from its author, might not be the most likely candidate for stage adaptation – but this project has just been undertaken by a team of artists and academics in Sheffield. William Baldwin’s Beware the Cat, written in 1553, will be performed in September as part of the university’s 2018 Festival of the Mind.

As a literary form, the novel is usually thought to have developed in the 18th century with the mighty classics Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe and Tristram Shandy by Laurence Sterne. But researchers believe we should be looking back to the relatively neglected prose fictions of the Tudor era to find the earliest English examples. Beware the Cat, an ecclesiastical satire about talking cats, is a prime candidate and is now thought to be the earliest example of the novel form in the English language.

Baldwin is barely known outside the circles of Renaissance literature, but he was highly celebrated and widely read in Tudor England. In the mid-16th century, he was earning an inky-fingered living as a printer’s assistant in and around the central London bookmaking and bookselling area of St Paul’s Cathedral. As well as writing fiction, he produced A Mirror for Magistrates, the co-written collection of gruesome historical poetry that was highly influential on Shakespeare’s history plays. He also compiled a bestselling handbook of philosophy, and translated the controversial Song of Songs, the sexy book of the Bible.

Beware the Cat tells the tale of a talkative priest, Gregory Streamer, who determines to understand the language of cats after he is kept awake by a feline rabble on the rooftops. Turning for guidance to Albertus Magnus, a medieval alchemist and natural scientist roundly mocked in the Renaissance for his quackery, Streamer finds the spell he needs. Then, using various stomach-churning ingredients, including hedgehog’s fat and cat excrement, he cooks up the right potion.

And it turns out that cats don’t merely talk – they have a social hierarchy, a judicial system and carefully regulated laws governing sexual relations. With his witty beast fable, Baldwin is analysing an ancient question, and one in which the philosophical field of posthumanism still shows a keen interest: do birds and beasts have reason?

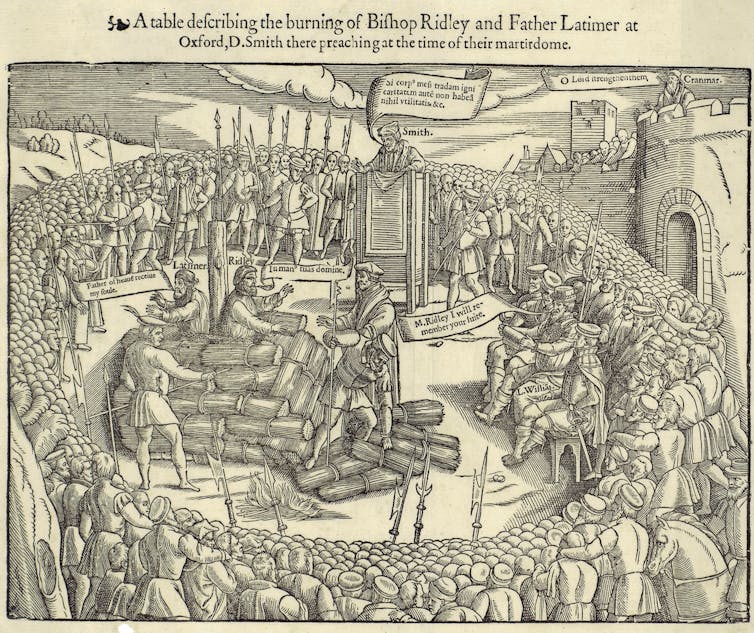

But rights and wrongs of a different order coloured Baldwin’s book release. He self-censored for several years before making the work public. Beware the Cat was written in 1553, months before the untimely death of the young Protestant king, Edward VI. Next on the throne (if you disregard the turbulent nine-day reign of Lady Jane Grey) was the first Tudor queen, Mary I. Her Catholicism was fervent and these were terrifying days. By the mid-1550s, Mary was burning Protestant martyrs. One of her less alarming, but still consequential, decisions was to reverse the freedoms accorded the press under her brother Edward.

At the height of his power during the 1540s, the Lord Protector during the young Edward’s reign, Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, had relied on particular printers to spread the regime’s reformist message. Men such as John Day (printer of Foxe’s Book of Martyrs) and Edward Whitchurch – Baldwin’s employer – printed and circulated anti-Catholic polemic on behalf of the state. Not content to persecute these men by denying them the pardon she accorded other Protestant printers, Mary I banned the discussion of religion in print unless it was specifically authorised by her officials.

As a print trade insider, Baldwin was intimately connected with the close community of this radical Protestant printing milieu – and Beware the Cat is deliberately set at John Day’s printing shop. Having written a book that parodies the Mass, depicts priests in some very undignified positions and points the finger at Catholic idolatry, Baldwin thought better of releasing it in the oppressive religious climate of Mary’s reign. But by 1561, Elizabeth I was on the throne and constraints on the press were less severe – despite the infamous case of John Stubbs, the writer who in 1579 lost his hand for criticising her marriage plans.

Baldwin, now in his 30s, had become a church deacon. He was still active as a writer and public figure, working on his second edition of A Mirror for Magistrates and preaching at Paul’s Cross in London, a venue that could attract a 6,000-strong congregation.

Once it was released, Beware the Cat went through several editions. It was not recognised for the comic gem that it is until scholars such as Evelyn Feasey started studying Baldwin in the early 20th century and the novel was later championed by American scholars William A. Ringler and Michael Flachmann.

Now, it has been adapted for performance for the first time and is being presented as part of the University of Sheffield’s Festival of the Mind. This stage version of Beware the Cat has been created by the authors with Terry O’Connor (member of renowned performance ensemble Forced Entertainment) and the artist Penny McCarthy.

Baldwin’s techniques of embedded storytelling, argument and satirical marginalia are all features that have been incorporated into this interpretation of the text. The production also includes an array of original drawings (which the cast of four display by using an onstage camera connected to a projector), but none of the cast pretends to be a cat. Instead, it is left to the audience to imagine the world Baldwin’s novel describes, in which cats can talk and – even if just for one night – humans can understand them.![]()

Rachel Stenner, Teaching Associate in Renaissance Literature, University of Sheffield and Frances Babbage, Professor of English Literature, University of Sheffield

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

4Max via Shutterstock

Sheena Kalayil, University of Manchester

Apparently, I am BAME. This places me as a contender for The Guardian’s BAME awards or the Jhalak prize, both aimed at BAME writers like myself. Ah, BAME – this acronym, which means black, asian and minority ethnic, joins many other appellations offered over the decades (not all of them very nice), painstakingly attempts to address the complexities of a multicultural society. But isn’t it, despite its best intentions, rather limiting?

As a child in Zambia, I was a mwenye, if the speaker wished to be disparaging (it’s an unflattering term that I won’t translate). In most contexts my family was “Indian”, while we regarded ourselves as Keralites (being Indian was secondary). Back in Kerala, if denoted by religion, we were proud to be “Syrian Christians”, members of a Catholic congregation pre-dating the arrival of Islam in India, formed by the disciple Doubting Thomas. Of course this meant we were a cut above those “Latin Christians” who had converted centuries after to curry favour with their Portuguese colonisers.

Later, as a teenager in a new Zimbabwe, I was once again “Indian” and, in a Harare which had been segregated under the Rhodesians, my family should thus have lived in the suburb of Belvedere, which was the Indian zone, rather than as we did on the edge of the “coloured” (mixed-race) Braeside. I resisted these tortuous preoccupations with skin tones and bloodlines – and by my late teens, inspired by the rising tide which was turning against apartheid in South Africa, I was resolutely, in my eyes, “black”.

But when I arrived in the UK, I was suddenly “Asian” – defined by a great continent, of which my home state in India was a mere slender slip of a thing. I was properly foreign, with a student visa stamped in my Indian passport, but my proficiency in English led many to believe I was “British Asian”, alongside an assumption that I was second-generation British, well versed in both Withnail and I and the career of reggae DJ Apache Indian, and full of fond memories of that incredible summer of 1976. I have done my homework since, as you can see.

I returned to Africa as a young woman, and when living and working in Mozambique, I was a monye – another disparaging term, not dissimilar to mwenye, but this sobriquet was seasoned with the erroneous assumptions of being Muslim and wealthy. Then, on to the tiny island of Bioko, part of Equatorial Guinea, where I was memorably known as la chica blanca – the white girl. Oh yes, and in Spain some years later, I was declared a hindou, the religious divisions that beset my homeland refreshingly ignored. Reader, an identity crisis in the making.

But, actually not. For, observers often overlook the id and the ego: your own innate understanding of yourself. Are we swayed so much by what others call us? Probably not. Despite my nomadic childhood, my peripatetic young adulthood, my membership of a wider diaspora, angst over love affairs and migrations and appearance and employment, if I’m honest, I’ve always known myself: as impulsive, restless, often inept, but well-intentioned. Despite all the assumptions made in the geographical/religious/social “names” I have been given, these qualities best define who I am.

The journey I have taken to arrive at the roles I currently have – wife, mother, writer, teacher – baffles many people. My first novel (roundly rejected, then published independently) juxtaposes a young woman’s passionate love affair in Mozambique with her arranged marriage in the US. My second, published as my debut by Polygon, follows a widower’s return to India after 30 years in London. My most recent, The Inheritance, features an affair between a young student and an older lecturer, the latter born in Zimbabwe-then-Rhodesia.

As a writer, if I tap into my experiences of geographical dislocations and multilingual communities, the literary industry and reviewers often locate the story as one of identity crises, of a quest to belong, in which I give “a compelling insight into what it means to be rootless, with characters torn between the culture of their parents and that of the society in which they grew up”. All true. But not the whole story and not a unique story by any means – instead, one that is shared by millions over a shifting, transient world, including readers of fiction. To a lot of us, the mobility and code-switching and reinvention are rather normal. What informs my sense of self? Whom I love, my children, the opinions and advice of the people who are important in my life.

It feels churlish to question BAME. But, if identifying a misrepresented or under-represented minority, then why not just “minority”? The writer and historian Paul Gilroy, in his book There Ain’t no Black in the Union Jack, has already queried the “imploded, narcissistic obsession with the minutiae of ethnicity”. Why the splintering and separation? Does the “B” in BAME reference the Windrush generation or the recently arrived Somali, or neither, or both?

Are we in danger of engendering a hierarchy by stealth, so some minorities are considered more “minority” than others? As a “British Asian” (holding a British passport now, I have become one) I cannot claim to have the same experiences and reception as a Briton with Nigerian origins. But I might well share some of her experiences if she is a woman (like me), if she is a writer (like me), or if she is as scared of her teenage daughter as I am.

And if we take the “A” – what constitutes a (British) Asian? Not all of us emanate from the Punjab or Gujarat or Bangladesh, or made a prolonged stopover in East Africa. Not all of our parents arrived in the UK in the 1960s or 1970s. Not all of live in a large, dense community, or speak its language – or even wish to. Not all of us dance bhangra or admire Bollywood. Our families may not all have served in or near the Raj and we may not have a strong memory of or feelings about partition.

Disappointed? You might well be, so embedded are the discourses surrounding British Asians. A discourse which can blind an “A” in BAME to the heterogeneity and diversity within – and which is perpetuated sometimes by these individuals themselves. I once watched on television a very well-known British Asian comic whose punchline centred on the unlikelihood of finding an Indian at a Catholic school. The laughter from the audience only served to show how they little knew of the millions of Indians who are Catholic. But, more depressingly – neither it seemed, buying into the discourse, did the comic.

To note, the aforementioned Jhalak prize, is the Hindi-Urdu word for “glance”. Considering it is open to all BAME writers, the Bs and the MEs alongside the As, perhaps this is not the most inclusive title?

<!– Below is The Conversation's page counter tag. Please DO NOT REMOVE. –>

![]()

Perhaps rather than trying to solve issues about diversity by making diversity more explicit and more fractured at the expense of cohesion, we should simply acknowledge that it is, frankly, impossible to categorise a creature as self-reflective and self-concerned as a human being.

Sheena Kalayil, Senior Language Tutor, University Language Centre, University of Manchester

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that considers how authors can use YouTube to their advantage.

For more visit:

https://goodereader.com/blog/digital-publishing/authors-can-take-advantage-of-piracy-via-youtube

The link below is to an article that takes a look at the subject of author photos.

For more visit:

https://lithub.com/the-agony-and-the-ecstasy-of-taking-author-photos/

The link below is to an article that takes a look at whether an author’s dying wishes should be observed.

For more visit:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/mar/10/up-in-smoke-should-an-authors-dying-wishes-be-obeyed

You must be logged in to post a comment.