Roland Sussex, The University of Queensland

Language is like archaeology. It lays down evidence for following generations to excavate and write PhD theses about. Layers of the stuff. And such has been the language of the year of COVID.

Not surprisingly, COVID has spawned an efflorescence of words and expressions. And these will certainly be dug up for analysis by our descendants.

In Australia we have a characteristic way of repurposing words, and we have applied it to COVID. Isolation became “iso”, which was crowned (joke: corona is Latin for crown) Word of the Year, or WOTY, by the Australian National Dictionary.

And coronavirus became “rona”, the Macquarie Dictionary’s COVID WOTY for 2020, announced today.

The Macquarie has departed from its usual practice (as has the Oxford English Dictionary) and anointed not one but two WOTYs (should that be WOTIES?): one to honour the way COVID has dominated our world, thinking and language this year; and another across-the-board WOTY as well. Their latter choice was “doomscrolling”, the practice of continuing to read news online or on social media when you know there’s nothing new in the news, and it’s all miserable.

Read more:

‘Iso’, ‘boomer remover’ and ‘quarantini’: how coronavirus is changing our language

Short, not necessarily sweet

Iso and rona are diminutives or hypocoristics. I have a database of over 6,000 of these in Australian English. These are derived forms of words that express an emotional overtone, usually amiable and solidaristic (“barbie” for barbecue; “servo” for service station), sometimes pejorative (“commo” for communist, “drongo” for well, an idiot).

But my personal nomination for the 2020 WOTY is “quazza” for quarantine. I predicted its birth and was fulfilled when it duly appeared.

Quazza follows a pattern in Australian English where R becomes Z: Terry gives “Tezza”, Barry gives “Bazza”, and quarantine yields “quazza”. Which is a long way from the Italian word quarantina, a reference to the 40-day period ships had to anchor off Italy in days gone by to prove there was no plague on board.

These diminutives serve an important purpose. They de-demonise threatening words. Without reducing the level of the words’ threat, the diminutives imply: this is something we can get our minds around and manage.

And gradually, with some temporary reversals, that is what we have done, and much more effectively than most other countries. Though whether the diminutives have medical force is not yet proven.

Unsplash, CC BY

Getting the message

Of course, there’s more to the influence of language under COVID than diminutives. In terms of public health and communication, three key agencies have driven our handling of the pandemic: scientists, policymakers and the public.

In Australia, the passage of information and action between these three entities has worked rather well. Science has transmitted reliable and helpful analyses of coronavirus and COVID-19 to policymakers. They informed our understanding of specific pandemic terms like “incubation” and “reinfection”.

State and federal governments have issued action guidelines with terms like “COVID safe”. And the public has created their own shorthand like the diminutives described above to make it all a bit friendlier.

Read more:

We’re not all in this together. Messages about social distancing need the right cultural fit

Australians have accessed the science through the media and the internet, and have generally acted responsibly.

Unsplash/United Nations, CC BY

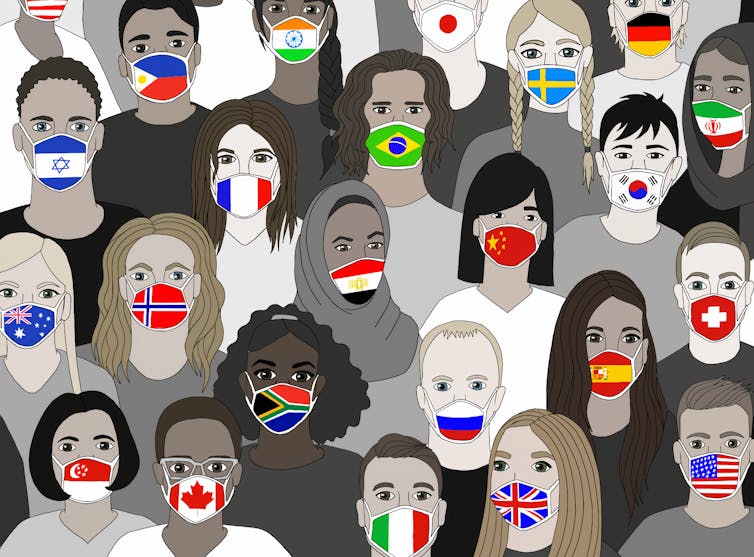

The key mechanism for communicating along the three axes between science, policymakers and the public involves messaging. Words matter in this context. What is needed is simple, direct, transparent and plausible language. Translations for multilingual communities are also vital.

Australian authorities have used words effectively and fairly consistently (though not always). The words and terms have fallen within four broad lexical categories:

1. isolation — lockdown, isolation, quarantine

2. distance — social distancing, venue capacity

3. hygiene — handwashing, sanitiser (or “hand sanny” in Australian slang), masks

3. social — COVID safe, flatten the curve, stop the spread, WFH (work from home).

The British messaging was much less effective, moving from “Protect the NHS” (National Health Service) to “Stay alert” without specifying what people should be alert to.

Going the distance

Unfortunately, many countries took up the phrase “social distancing”, when what was needed was “physical distancing”, continuing social interaction as an important part of maintaining well being. The World Health Organisation agrees.

Next time — and there certainly will be a next time — we need to be better prepared.

There will be new vocabulary to describe, and perhaps to help tame, potential new threats. The messaging may be very similar, and we will know, from our experience with COVID-19 in 2020, how best to stop “covidiots” from acting “coronacrazy”.

Read more:

How COVID-19 is changing the English language

![]()

Roland Sussex, Professor Emeritus, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.