Angelica Kauffmann/Hermitage/Wikimedia Commons

Chris Mackie, La Trobe University

The Aeneid by the Roman poet Virgil is an epic poem in 12 books that tells the story of the foundation of Rome from the ashes of Troy. It was probably written down in Rome from 30-19 BC during the period of the Emperor Augustus.

The poem is named after the Trojan hero Aeneas, the son of Venus (Aphrodite in Greek mythology) and Anchises, a Trojan aristocrat. Aeneas leads the survivors from the sack of Troy through the Mediterranean, and ultimately to the site of (future) Rome. The Aeneid is therefore a classic foundation narrative.

As with other ancient epics, our hero has to remain resolute in the face of significant divine hostility. Juno, queen of heaven and goddess of marriage, despises the Trojans because she lost a divine beauty contest known as the Judgement of Paris. Venus wins the Judgement by giving a bribe to Paris, a Trojan prince who acts as judge. The bribe is in the form of Helen of Sparta, the most beautiful woman in the world. Paris prefers this bribe to the bribes of the other two contestants – Juno and Minerva.

Read more: Guide to the Classics: Homer’s Iliad

Unfortunately, Helen is already married to the Spartan king Menelaus, and so the Trojan war follows soon after. Juno takes badly her loss in the beauty contest, and hates everything Trojan, both during the war, and after. The hatred and vindictiveness shown by Juno to the Trojans anchors the whole Aeneid, and it only comes to an end in the final book.

Stealing from Homer?

The Aeneid is written in dactylic hexameters, the same metre as the two Homeric poems – the Iliad and Odyssey (although it is written in Latin, not in ancient Greek).

In many ways the Aeneid is written in emulation of Homer’s works by a poet who may have known them off by heart (that is my view, anyway). Scholars sometimes talk about the “Odyssean” Aeneid (Books 1-6, because Aeneas travels through the Mediterranean, a bit like Odysseus), and the “Iliadic” half of the poem (Books 7-12, on the theme of war in Italy).

A new reader of the Aeneid with a background in Homer can usually identify many passages that have Homeric resonances.

Penguin

Indeed many readers through time have felt that Virgil is too reliant on Homer. There is a story that Virgil needed to defend himself from this charge by saying that “it is easier to steal Hercules’ club than steal one line from Homer”.

It must be stressed, however, that in Virgil’s case, we are dealing with someone who was totally immersed in Greek and Roman literature, rhetoric and philosophy – not just the works of Homer. He was an astonishingly well-read poet, and this breadth of learning is embodied in his poems. In this sense the criticism of Virgil of plagiarising Homer, or quasi-plagiarism, seems rather unreasonable.

A deserted heroine

The Aeneid’s thematic connections to earlier myth and literature come to the fore in the depiction of Dido, the queen of Carthage. Dido is the great tragic figure in the first half of the poem (notably in Books 1, 4, and 6) after a romance and sexual liaison with Aeneas.

The figure of the deserted heroine was a favourite theme in Greek myth and literature, and Virgil duly draws on it for his depiction of Dido. Such heroines included Medea, Phaedra, Ariadne, and Hypsipyle. There was also an early Roman depiction of Dido by Gnaeus Naevius (270-201 BC) in his epic The Punic War.

Thus it would be a mistake to reduce Virgil’s Dido to some kind of re-creation of Homer’s Calypso, or Circe, or Nausicaa (all from the Odyssey). Indeed, Virgil’s audience may have responded to the tragedy of Dido in the Aeneid by thinking of another North African queen – Cleopatra (69-30 BC), with whom both Julius Caesar and Mark Antony had flings. So the general point here is that the reader of the Dido books is invited to engage with many different mythical and historical narratives.

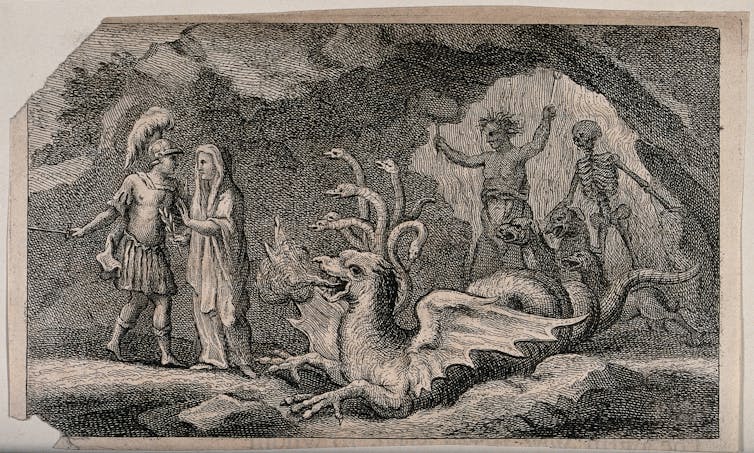

Wellcome Images/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

Virgil’s method of composition of his poetic works was slow and deliberate, and quite “un-Homeric” in all kinds of ways. “Homer” (ca. 700 BC) was a highly skilled oral poet who used this expertise to create his story, whereas Virgil (70-19 BC) lived in a thoroughly literate society. The pace of poetic creativity could be very slow.

The Georgics, an earlier poetic work by Virgil on the subject of agriculture (2,188 lines), seems to have been written at a rate of about one line a day. And the Aeneid itself (9,883 lines) works out to about three lines a day. Little wonder that it is so succinct and complex.

The Aeneid is certainly not the easiest read from the corpus of ancient literature. There is some evidence that Virgil wrote it first in prose, before developing the poetic version. It is also an unfinished poem, although still remarkably polished.

Returning home

Even though the Aeneid is a foundation narrative where the Trojans struggle to find a new home after the destruction of their city, it is important to stress that it is also a “return” (that is, a Greek “nostos”).

Troy was founded by Dardanus, an obscure mythological hero, and, in Virgil’s poem, he did so having left from a place called “Corythus” (perhaps modern Cortona in Tuscany). The story in the Aeneid is that many generations later – after the sack of Troy – Aeneas leads his people back to Italy as a kind of “new Dardanus”.

Aeneas’s quest, then, is both a new mission to a new land and a return to the ancestral land of the first Trojan. The return journey of a hero from war was a favourite Greek mythical narrative (including the Odyssey of course). Virgil follows suit in the Aeneid, but offers a much more complex notion of the heroic “return”.

Read more: Guide to the Classics: Homer’s Odyssey

Aeneas is a very different kind of epic hero from Achilles in the Iliad and Odysseus in the Odyssey, not the least because he is imbued with a whole series of distinctly Roman values. He is a much more “religious” kind of hero – someone who makes it his business to follow the path that has been ordained for him and his people.

A characteristic epithet for Aeneas is pius (“pious”, “duty-bound”, “dutiful”). Indeed his whole quest is really to unravel the mysteries of fate, and then duly to act upon them. He tends to focus on the “greater good”, sometimes with an element of personal suffering (perhaps along Stoic lines). For instance, he deserts Dido (in Book 4) because Jupiter reminds him through the god Mercury that Italy is meant to be his fated home, not Carthage in North Africa.

University of Toronto/Wikimedia Commons

The Aeneid looks back to a time well before the foundation of the city of Rome, and forward to the realities of Roman imperialism up to Virgil’s own day. The past and the future often seem entangled in all kinds of ways, and then there is the question of Virgil’s own political outlook. Is the poem designed to justify and support Rome’s imperialist agenda?

The English poet W.H. Auden was rather unsympathetic to Virgil in his poem Secondary Epic (1959):

No, Virgil, no:

Not even the first of the Romans can learn

His Roman history in the future tense.

Not even to serve your political turn;

Hindsight as foresight makes no sense.

…

No, Virgil, no:

Behind your verse so masterfully made

We hear the weeping of a Muse betrayed.

The Aeneid, therefore, is focused on the grand scale – on the city of Rome and its empire, its formation, and its destiny within the order of the Olympian gods. Scholars, poets and critics, often against a background of modern wars (such as WWII or Vietnam), have agonised over the question of Virgil’s own attitude to war and the Augustan imperial agenda, which receives some considerable attention at critical moments in the Aeneid.

Augustus, after all, seems to have been a generous patron of the poet, and a certain amount of text-specific adulation might have been expected. Auden certainly felt that Virgil traded in his poetic respectability (“your political turn”… “a Muse betrayed”). But there have also been plenty of others who are prepared to claim that Virgil yearns for peace, and actually undercuts the explicit patriotism about Rome and Augustus.

A violent end

The final scene of the Aeneid tends to polarise critical views on the basic thrust of the poem. Whereas the Homeric poems end in an atmosphere of peace and tranquillity, Virgil’s Aeneid ends with unremitting violence.

Aeneas’s great Italian warrior rival Turnus has been wounded in single combat, and pleads for his life on his knees. Aeneas seems to mull over an act of clemency, but in a sudden fit of rage he kills Turnus on the spot. The poem ends with a description of Turnus’s limbs going slack and his life going resentfully to the shades below.

David Bjorgen/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

The sudden end of the Aeneid, with such a violent turn, has proved very challenging and unsatisfying for many readers. Virgil’s own death before the final completion of the poem in 19 BC added a further element of debate. Would he have changed the end of the poem? There was also a legend that he had left instructions for his assistants to burn the manuscript of the Aeneid, should he die before its completion.

The sudden and brutal end of the poem precipitated various sequels, most famously a Supplement to Aeneid Book 12 by the humanist cleric Maffeo Vegio (ca. 1406-58). This was basically a thirteenth book of the Aeneid told in 630 lines and written in 1428.

Vegio continues the narrative where Virgil leaves off, justifying the death of Turnus, and telling ultimately of the deification of Aeneas. The presence of sequels like this indicates just how confronting and original the Aeneid is – so much that later poets needed to “normalise” it.

There is every reason to think that Virgil’s Aeneid became a classic as soon as it was written and published. And it has remained so until this day. Many parts of the Aeneid have influenced Western literature and art: especially the sack of Troy and Aeneas’ departure from it (Book 2); the tragedy of Dido (Books 1, 4 and 6); and his journey to the Underworld (Book 6).

Jean-Baptiste Wicar/Chicago Art Institute/Wikimedia Commons

The last of these, Aeneas’s journey into the Underworld in Aeneid 6, fundamentally influenced the poet Dante’s (1265-1321) own narrative of life after death. Virgil is his guide through Inferno and Purgatorio, which says something about the high regard of poet for poet – bearing in mind, of course, that Virgil was a pagan.

When Dante first sees the shade of Virgil he greets him in a way that could hardly be more fulsome:

Are you then that Virgil, and that fountain, that pours out so great a river of speech? O, glory and light to other poets, may that long study, and the great love, that made me scan your work, be worth something now. You are my master, and my author: you alone are the one from whom I learnt the high style that has brought me honour.

![]() *NB Virgil’s name is also sometimes spelt “Vergil.”

*NB Virgil’s name is also sometimes spelt “Vergil.”

Chris Mackie, Professor of Classics, La Trobe University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.