The link below is to an article that claims children who own more books read better – which is fairly obvious I suppose.

For more visit:

https://lithub.com/children-who-own-books-more-likely-to-be-good-readers-reveals-obvious-study/

The link below is to an article that claims children who own more books read better – which is fairly obvious I suppose.

For more visit:

https://lithub.com/children-who-own-books-more-likely-to-be-good-readers-reveals-obvious-study/

The link below is to an article that considers how many books you should read at a time. I have had up to twenty something on the go at any one time this year – how about you?

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2019/12/04/how-many-books-should-you-read-at-once/

Elisabeth Gruner, University of Richmond

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com.

Why do teachers make us read old stories? Nathan, 12, Chicago, Illinois

There are probably as many reasons to read old stories as there are teachers.

Old stories are sometimes strange. They display beliefs, values and ways of life that the reader may not recognize.

As an English professor, I believe that there is value in reading stories from decades or even centuries ago.

Teachers have their students read old stories to connect with the past and to learn about the present. They also have their students read old stories because they build students’ brains, help them develop empathy and are true, strange, delightful or fun.

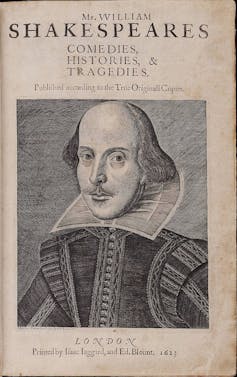

In Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet,” for example, teenagers speak a language that’s almost completely unfamiliar to modern readers. They fight duels. They get married. So that might seem to be really different from today.

And yet, Romeo and Juliet fall in love and make their parents mad, very much like many teens today. Ultimately, they commit suicide, something that far too many teens do today. So Shakespeare’s play may be more relevant than it first seems.

Additionally, many modern stories are based on older stories. To name only one, Charlotte Brontë’s “Jane Eyre” has turned up in so many novels since its original publication in 1848 that there are entire articles and book chapters about its influence and importance.

For example, I found references to “Jane Eyre” lurking in “The Princess Diaries,” the “Twilight” series and a variety of other novels. So reading the old story can enrich the experience of the new.

Reading specialist Maryanne Wolf writes about the “special vocabulary in books that doesn’t appear in spoken language” in “Proust and the Squid.” This vocabulary – often more complex in older books – is a big part of what helps build brains.

The sentence structure of older books can also make them difficult. Consider the opening of almost any fairy tale: “Once upon a time, in a very far-off country, there lived …”

None of us would actually speak like that, but older stories put the words in a different order, which makes the brain work harder. That kind of exercise builds brain capacity.

Stories also make us feel. Indeed, they teach us empathy. Readers get scared when they realize Harry Potter is in danger, excited when he learns to fly and happy, relieved or delighted when Harry and his friends defeat Voldemort.

Older stories, then, can provide a rich depth of feeling, by exposing readers to a broad range of experiences. Stories featuring characters from a diverse range of backgrounds or set in unfamiliar places can have a similar effect.

Old stories are sometimes just so weird that you can’t help but enjoy them. Or I can’t, anyway.

In Charles Dickens’ “Great Expectations,” there’s a character whose last name is “Pumblechook.” Can you say it without smiling?

In Lewis Carroll’s “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland,” a cat disappears bit by bit, eventually leaving only its smile hanging in the air. Again, new stories are also lots of fun, but the fun in the older stories may turn up in those new stories.

For example, that cat returns in many newer tales that aren’t even related to Alice in Wonderland, so knowing the cat’s history can make reading that new story more pleasurable.

I won’t deny that some old stories contain offensive language or reflect attitudes that we may not want to embrace. But even those stories can teach readers to think critically.

Not every old story is good, but when your teacher asks you to read one, consider the possibility that you might build your brain, grow your feelings or have some fun. It’s worth a try, at least.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

[ You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter. ]![]()

Elisabeth Gruner, Associate Professor of English, University of Richmond

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Katina Zammit, Western Sydney University

When I was younger I decided to learn Greek. I learnt the letter-sound correspondences and could say the words – the sounds, that is. But although I could and still can decode these words, I can’t actually read Greek because I don’t know what the words mean.

Being able to make the connection between the letters, their combinations and the sounds that make up the words wasn’t all I needed to be able to read. It was an easy way to learn but it didn’t provide me with the whole picture.

As we read, and understand what we are reading, we don’t just use our knowledge of the letter-sound correspondences, which you may know as phonics or phonemic awareness, we also use other cues. These include our knowledge of the topic, the meaning of words in the context of the topic, and the flow and sequence of the words in a sentence.

Good readers use a full repertoire of skills, each dependent on the other. And a whole language approach to teaching reading is about arming new readers with this repertoire.

A whole language approach to teaching reading was introduced into primary schools in the late 1970s. There have been many developments in this area since, so the approach has been adapted and today looks quite different from 40 years ago.

To begin with, let’s dispel some myths about a whole language approach to teaching reading. It is not learning to read individual words by sight. Nor is it learning a list of vocabulary only.

A whole language approach to teaching reading is not opposed to teaching the correspondence of a letter or letters to sounds to help sound out unfamiliar words. Nor is it opposed to learning how to blend sounds together to decode a word by using the first letter/s of a word, the end of the word and the letter/s in the middle.

Read more:

Reading progress is falling between year 5 and 7, especially for advantaged students: 5 charts

But just knowing sounds is not the same as knowing how to read. In 2000, the US National Reading Panel’s analysis of scientific literature on teaching children to read found systematic phonics instruction (teaching sounds and blending them together) should be integrated with other reading instruction to create a balanced reading program.

The panel determined that phonics instruction should not be a total reading program, nor should it be a dominant component.

In 2011, the UK introduced a mandatory phonics screening check, for year 1 students, to address the decline in literacy achievement in the middle years of school. Children were prepared for the test using a government-approved synthetic phonics program. But in 2019 around 25% of year 6 students failed to reach the minimum requirements in reading.

Read more:

The Coalition’s $10 million for Year 1 phonics checks would be wasted money

Australia’s own national inquiry into teaching literacy noted the same conclusions as the US national reading panel.

This view aligns with the whole language approach in the 21st century, which advocates a balanced way of teaching reading in the early years. This includes:

The whole language approach provides children learning to read with more than one way to work out unfamiliar words. They can begin with decoding – breaking the word into its parts and trying to sound them out and then blend them together. This may or may not work.

They can also look at where the word is in the sentence and consider what word most likely would come next based on what they have read so far. They can look beyond the word to see if the rest of the sentence can assist to decode the word and pronounce it.

We do not read texts one word at a time. We make best guesses as we read and learn to read. We learn from our errors. Sometimes these errors are not that significant – does it matter if I read Sydenham as “SID-EN-HAM” or “SID-N-AM”? Perhaps not.

Does it matter that I can decode the word “wind” but don’t pronounce the two differently in “the wind was too strong to wind the sail”? Yes, it probably does.

Teaching children to read or to see reading with a focus on phonics and phonemic awareness gives them the illusion “proper” reading is mere decoding and blending. In fact, it has been argued this can put children off reading when entering school. While some gain may occur in the first years, over time achievement deteriorates for children in high-performing and low-performing schools.

Read more:

Enjoyment of reading, not mechanics of reading, can improve literacy for boys

A whole language approach doesn’t argue against the importance of phonemic awareness. But it acknowledges it is not all that should be included in reading instruction.

It is important to assess children’s reading from the beginning of schooling and continually determine how they are progressing. Teachers can then select specific strategies to improve individual children’s reading competence and increase their skills to build fluent and confident readers.

A whole language approach to teaching reading advocates for teaching phonics and phonemic awareness in the context of real texts – that use the richness of the English language – not artificial, highly constructed texts. However, it also acknowledges this is not sufficient. Being able to decode the written word is essential, but it isn’t enough to set up a child to be a competent reader and to be successful during and after school.

Read the accompanying article on teaching to read using explicit phonics instruction here.![]()

Katina Zammit, Deputy Dean, School of Education, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

There is a hidden problem with reading in Australian schools. Ten years’ worth of NAPLAN data show improvements in years 3, 5 and 9. But reading progress has slowed dramatically between years 5 and 7.

And, somewhat surprisingly, the downward trend is strongest for the most advantaged students.

Years 5-7 typically include the transition from primary to secondary school. Yet the reading slowdown can’t just be blamed on this transition, because numeracy progress between the years has improved. So, what is going wrong with reading?

Progress in reading is like climbing a mountain. The better your reading skills, the higher you are. The higher you are, the further you can see. And the further you can see, the more sense you can make of the world.

Like a real mountain, the reading mountain must be tackled in stages. NAPLAN – the National Assessment Program, Literacy and Numeracy – provides insight into those stages, by measuring reading skills at years 3, 5, 7 and 9.

The good news is that the average level of reading skills of year 3 students – reading base camp – is getting higher.

To make the results easier to interpret, I’ve converted the NAPLAN data into the equivalent year level of reading achievement. For instance, in 2010, children in year 3 were reading at equivalent year level 2.6 when they sat NAPLAN. This means they were four-and-a-half months behind a benchmark set at the long-run average for metropolitan non-Indigenous students.

By 2019, the mean reading achievement among all year 3 children was equivalent to year 3.0, meeting this benchmark.

Over ten years, the improvement has been worth about five months of extra learning.

There is more good news in secondary school. Recent cohorts have made better progress between years 7 and 9 than earlier cohorts. My best estimate is that learning progress has increased by almost three months of learning over this two-year stage of schooling.

Students in years 3-5 haven’t made the same gains. But (if anything) they are heading in the right direction.

Something is going wrong between year 5 and 7. Students are making six months less progress than they used to. It’s not that they are getting worse at reading; they just aren’t climbing as fast as previous cohorts.

This drop in reading progress can’t simply be attributed to the transition from primary to secondary. Among other things, numeracy progress during this stage of schooling has increased by about six months since 2010.

It’s as if students have started skipping a term in each of their final two years of primary school, but only in English, not in maths. And not all groups of students are affected equally.

Reading progress has slowed the most for students from advantaged backgrounds. For instance, students whose parents are senior managers make ten months less progress from year 5 to 7 than earlier cohorts.

Interestingly, the student groups with the biggest slowdown in years 5-7 have also shown the most improvement in year 5 reading.

This pattern – big gains in year 5 that evaporate by year 7 – rules out poor early reading instruction as a cause. This reading problem isn’t about phonics, but a failure to stretch students in upper primary school.

My analysis also shows:

Maybe some primary school teachers focus more on helping students reach a good minimum standard of reading, and not on how far they go. This fits with the trend in year 5; no need to push hard if students are already doing well.

But it doesn’t explain the large drop in progress in Queensland and WA the year they shifted year 7 to secondary school.

Maybe schools push hard on literacy and numeracy until students have done their last NAPLAN test in that school. This would help explain the 2015 drop in reading progress for Queensland and WA, but not the divergent picture for reading and numeracy progress, including in the Queensland/WA change-over year.

Maybe students are reading less as technology becomes ubiquitous. This could explain the difference between reading and numeracy. But why would it reduce progress between years 5 and 7 but not between years 3 and 5 or 7 and 9?

Increased use of technology also fails to explain the sudden slump in Queensland and WA in 2015.

Other potential explanations need to explain the complex pattern of outcomes, including the fact the reading slowdown is so widespread even while numeracy progress is going the other way.

My best guess is that some advantaged primary schools focus on literacy and numeracy until the year 5 NAPLAN tests are done, but then switch to project-based learning, leadership or year 6 graduation projects. These “gap year” activities don’t displace maths hour (which drives numeracy progress) but may disrupt reading hour or other activities that build reading skills.

Meanwhile, disadvantaged primary schools are very aware of the need to keep building their students’ reading levels to set them up for success in secondary school.

This story is speculative, but it fits the data.

Education system leaders need to figure out what is happening in reading between years 5 and 7, and quickly. They should look closely at upper primary years, as well as the transition to secondary school. This is much more subtle than a traditional back-to-basics narrative.

In the meantime, teachers in years 5, 6 and 7 should be aware their students are making less progress than previous cohorts, and focus on extending reading capabilities for students who are already doing well. All students deserve to climb higher on their reading mountain.![]()

Peter Goss, School Education Program Director, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that takes a look at social reading and social reading apps.

For more visit:

https://www.makeuseof.com/tag/best-social-reading-apps/

The link below is to an article that raises the question of reading on a tablet – why you should consider it.

For more visit:

https://goodereader.com/blog/tablet-slates/why-you-should-consider-reading-on-a-tablet

The link below is to an article that explores why some people become lifelong readers.

For more visit:

https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2019/09/love-reading-books-leisure-pleasure/598315/

The link below is to an article with some tips on how to read slowly.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2019/10/07/how-to-read-slowly/

The link below is to an article reporting on how many thousands of people are now reading novels on Instagram.

For more visit:

https://ebookfriendly.com/people-reading-novels-instagram/

You must be logged in to post a comment.