The link below is to an article that takes a look at 13 free reading apps.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2018/11/08/free-reading-apps/

The link below is to an article that takes a look at 13 free reading apps.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2018/11/08/free-reading-apps/

The link below is to an article that looks at ways to balance reading multiple books at once.

For more visit:

https://www.epicreads.com/blog/reading-multiple-books-tips/

The link below is to an article that takes a look at reading and depression – does reading help?

For more visit:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2018/oct/26/just-how-helpful-is-reading-for-depression

Viacheslav Nikolaenko via Shutterstock

Sara Haslam, The Open University; Edmund King, The Open University, and Siobhan Campbell, The Open University

Bibliotherapy – the idea that reading can have a beneficial effect on mental health – has undergone a resurgence. There is mounting clinical evidence that reading can, for example, help people overcome loneliness and social exclusion. One scheme in Coventry allows health professionals to prescribe books to their patients from a list drawn up by mental health experts.

Even as public library services across Britain are cut back, the healing potential of books is increasingly recognised.

The idea of the healing book has a long history. Key concepts were forged in the crucible of World War I, as nurses, doctors and volunteer librarians grappled with treating soldiers’ minds as well as bodies. The word “bibliotherapy” itself was coined in 1914, by American author and minister Samuel McChord Crothers. Helen Mary Gaskell (1853-1940), a pioneer of “literary caregiving”, wrote about the beginnings of her war library in 1918:

Surely many of us lay awake the night after the declaration of War, debating … how best we could help in the coming struggle … Into the mind of the writer came, like a flash, the necessity of providing literature for the sick and wounded.

The well-connected Gaskell took her idea to the medical and governmental authorities, gaining official approval. Lady Battersea, a close friend, offered her a Marble Arch mansion to store donated books, and The Times carried multiple successful public appeals. As Gaskell wrote:

What was our astonishment when not only parcels and boxes, but whole libraries poured in. Day after day vans stood unloading at the door.

Gaskell’s library was affiliated to the Red Cross in 1915 and operated internationally – with depots in Egypt, Malta, and Salonika. Her operating principles, axiomatic to bibliotherapy, were to provide a “flow of comfort” based on a “personal touch”. Gaskell explained that “the man who gets the books he needs is the man who really benefits from our library, physically and mentally”.

Her colleagues running Endell Street Military Hospital’s library shared similar views about the importance of books in wartime. On August 12, 1916, the Daily Telegraph reported on the hospital, calling the library a “story in itself”. Run by novelist Beatrice Harraden, a member of the Womens Social and Political Union and also, briefly, the actress and feminist playwright Elizabeth Robins, the library was a fundamental part of the treatment of 26,000 wounded between 1915 and 1918.

“We learned,” Robins wrote in Ancilla’s Share, her 1924 analysis of gender politics, “that the best way, often the only way, to get on with curing men’s bodies was to do something for their minds.”

The books the men wanted first were likely to be by the ex-journalist and popular writer Nat Gould, whose novels about horseracing were bestsellers. Otherwise, fiction by Rudyard Kipling, Marie Corelli, or Robert Louis Stevenson rated highly. In the Cornhill Magazine in November, 1916, Harraden revealed that the librarians’ “pilgrimages” from one bedside to another ensured what she called “good literature” was always within reach, but that the book that would “heal” was the one that was most wanted:

However ill [a patient] was, however suffering and broken, the name of Nat Gould would always bring a smile to his face.

The literary caregivers at Endell Street worked responsively, and without judgement, a crucial legacy.

Literary caregiving also took place closer to the front. Throughout the war, the YMCA operated a network of recreation huts and lending libraries for soldiers. After losing his only son, Oscar, at Ypres, the author E. W. Hornung offered his services to the YMCA. Hornung – a relatively obscure figure now, but a literary celebrity then – authored the “Raffles” stories about the gentleman thief of the same name.

Arriving in France in late 1917, Hornung was initially put to work serving tea to British soldiers. But the YMCA soon found him a more suitable job, placing him in charge of a new lending library for soldiers in Arras. Dispensing tea and books to soldiers helped him process his grief. Hearing soldiers talk about their favourite books played a key role in his recovery – but he also sincerely believed that reading helped soldiers keep their minds healthy while they were in the trenches. Hornung wrote in 1918 that he wanted to feed “the intellectually starved”, while “always remembering that they are fighting-men first and foremost, and prescribing for them both as such and as the men they used to be”.

Present-day veterans encounter the potential of reading and writing in equally participatory ways as interventions with the charities Combat Stress UK (CSUK) and Veterans’ Outreach Services demonstrate.

In CSUK, we read widely from contemporary work before undertaking writing exercises. These were designed to help provide detachment from the internal repetition of traumatic stories that some with PTSD experience. The director of therapy at CSUK, Janice Lobban, says:

Collaborative work … gave combat stress veterans the valuable opportunity of developing creative writing skills. Typically, the clinical presentation of veterans causes them to avoid unfamiliar situations and the loss of self-confidence can affect the ability to develop creative potential. Workshops within the safety of our Surrey treatment centre enabled veterans to have the confidence to experiment with new ideas.

Another approach, in workshops with Veterans’ Outreach Support in Portsmouth in 2018, explored the role of writing in training veterans to become “peer-mentors” of other veterans wanting to access VOS services, ranging from physical and mental wellness to housing benefits to job-seeking.

The results show that veterans responded positively to opportunities for imaginative writing. Trainee peer-mentors responding to a questionnaire told us that the exercises helped them to write fluently about their own lives. For people who spend so much time filling out forms to access various benefits, the opportunity to write creatively was seen as a liberating experience. As one veteran put it: “We are writing into ourselves”.

For 100 years now, reading and writing have helped veterans build relationships, gain confidence and face the challenges of their post-service lives. Our current research charts the influence of wartime literary caregiving on contemporary practice.![]()

Sara Haslam, Senior Lecturer in English, The Open University; Edmund King, Lecturer in English, The Open University, and Siobhan Campbell, Lecturer of Creative Writing, The Open University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Simmone Pogorzelski, Edith Cowan University and Robyn Wheldall, Macquarie University

A child’s early experiences with books both at home and later in school have the potential to significantly affect future reading performance. Parents play a key role in building oral language and literacy skills in the years prior to school. But it’s teachers who are responsible for ensuring children become readers once at school.

While there’s much we know about how students learn to read, research on books used to support beginning reading development is sparse. Guidelines provided in the Australian Curriculum

and the National Literacy Progressions complicate matters further. Teachers are required to use two types of texts: decodable and predictable books.

Read more:

Explainer: what is phonics and why is it important?

Each book is underpinned by a different theory of reading, arguably in conflict. This contributes to uncertainty about when and how the books might be used.

Predictable books and their associated instructional strategies align with a whole-language approach to reading.

In this approach, meaning is prioritised. Children are encouraged to draw on background knowledge, memorise a bank of the most common words found in print, and to use cues to guess or predict words based on pictures and the story. This method is not consistent with a phonics approach.

At the earliest levels, predictable and repetitive sentences scaffold beginning readers’ attempts at unknown words. Word identification is supported by close text to picture matches and familiar themes for children in the early years (such as going to the doctor).

While there is some evidence the repetitive nature of predictable books facilitates the development of fluency, the features contained within disadvantage young readers as they do not align with the letter-sound correspondences taught as part of phonics lessons. This is particularly problematic for children who are at risk of later reading difficulties.

In comparison, decodable books consist of a high percentage of words in which the letters represent their most common sounds. Decodable books align with a synthetic phonics or code-based approach to reading. This approach teaches children to convert a string of letters (our written code) into sounds before blending them to produce a spoken word.

When reading decodable books, children draw on their accumulating knowledge of the alphabetic code to sound out any unknown words. Irregularly spelt words (for example was, said, the) are also included, and children receive support to read these words, focusing on the sounds if necessary.

There is mounting evidence for the use of decodable books to support the development of phonics in beginning readers and older kids who haven’t grasped the code easily. Decodable books have been found to promote self-teaching, helping children read with greater accuracy and independence. This leads to greater gains in reading development.

Children need lots of opportunities to practise reading words in books. Given research demonstrates a synthetic phonics approach provides young readers with the most direct route to skilled reading, there’s a strong logical argument for supporting early reading with decodable books.

Read more:

As easy as ABC: the way to ensure children learn to read

Until the most recent version of the Australian Curriculum, only predictable books were included in the Foundation and Year one English curricula. The addition of decodable books recognises the critical support they provide beginning readers. But this places teachers in a difficult position because the elaborations in the curriculum documents place more emphasis on the strategies designed primarily for use with predictable books.

While reading is an extraordinarily complex process, a model of reading called the Simple View of Reading is very helpful from an educational perspective. It explains skilled reading as the product of both decoding and language comprehension. This helps us understand what we need to do when teaching children to read, and the types of books they need to support early reading development.

Before they enter school, the majority of children are considered to be in the “pre-alphabetic” stage of reading. In this stage, children have little or no understanding the written code represents the sounds of spoken language. They would not have the skills to use decodable books.

Instead, they recognise words purely by contextual clues and visual features. For example, children know the McDonalds sign because of the big yellow arches (the M) or can read the word “stop” when they see the sign, but not out of that context.

Predictable books would help the pre-alphabetic reader gain insight into the workings of texts, especially with regard to meaning. In particular making the connection between spoken words – which they are familiar with – and written words, which they are not.

Beyond this stage, predictable texts become less useful because memorisation and meaning-based strategies aren’t sustainable long term. Once children have advanced to the partial and full alphabetic stages of reading, usually fairly quickly after starting formal reading instruction, they benefit more from decodable books which allow them to apply the alphabetic code.

There is no evidence children benefit from the continued use of decodable books beyond the beginning stages of reading. In the absence of any empirical studies, we suspect it would be a good idea to move children on once they have sufficient letter-sound knowledge and decoding skills that they can apply independently. At this point, the introduction of real books would benefit students and provide access to more diverse language structures and vocabulary.

Read more:

International study shows many Australian children are still struggling with reading

Given what we know about how reading works, it makes sense for children in the early stages of learning to read to be given decodable books to practise and generalise their developing alphabetic skills. At the same time, they will continue to benefit from hearing the rich vocabulary and language forms in the children’s books being read with (to) them.

It’s less clear what predictable texts contribute to beginning reading in schools when considering how reading skills develop. But there is evidence they might have a useful role to play in pre-school prior to the start of formal reading instruction.![]()

Simmone Pogorzelski, PhD Candidate, Sessional Academic, Edith Cowan University and Robyn Wheldall, Honorary Fellow, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Anita Collins, University of Canberra and Misty Adoniou, University of Canberra

Neuroscience has found a clear relationship between music and language acquisition. Put simply, learning music in the early years of schooling can help children learn to read.

Music processing and language development share an overlapping network in the brain. From an evolutionary perspective, the human brain developed music processing well before language and then used that processing to create and learn language.

At birth, babies understand language as if it was music.

They respond to the rhythm and melody of language before they understand what the words mean.

Babies and young children mimic the language they hear using those elements of rhythm and melody, and this is the sing-song style of speech we know and love in toddlers.

The foundation of reading is speech and to learn how to speak, children must first be able to distinguish speech from all other sounds. Music helps them do this.

Reading is ultimately about making meaning from the words on the page. A number of skills combine to help us make those meanings, including the ability to distinguish between the sounds in words, and fluency of reading.

Read more:

How do we learn to read?

Fluency includes the ability to adjust the the patterns of stress and intonation of a phrase, such as from angry to happy and the ability the choose the correct inflection, such as a question or an exclamation. These highly developed auditory processing skills are enhanced by musical training.

Musically trained children also have better reading comprehension skills.

Music can also give us clues about a child’s struggles with reading.

Research has found three- and four-year-old children who could keep a steady musical beat were more reading-ready at the age of five, than those who couldn’t keep a beat.

Language learning starts from day one of life with parents talking and singing to their babies. Babies bond with their parents and community primarily through their voice, so singing to your baby both forms a bond with them and engages their auditory processing network.

Taking toddlers to a well-structured, high quality music class each week will build the musical skills that have been found to be so effective in learning to read. It is vital to look for classes that include movement activities, singing, and responding to both sound and silence. They should use good quality music-making toys and instruments.

As they head into preschool, a crucial time for language development, look for the same well-structured music learning programs delivered daily by qualified educators. The songs, rhymes and rhythm activities our children do in preschool and daycare are actually preparing them for reading.

Read more:

Does your child struggle with spelling? This might help

Music programs should build skills sequentially. They should encourage children to work to sing in tune, use instruments and move in improvised and structured ways to music.

Children should also be taught to read musical notation and symbols when learning music. This reinforces the symbol to sound connection which is also crucial in reading words.

Importantly, active music learning is the key. Having loud music on in the background does little for their language development and could actually impede their ability to distinguish speech from all the other noise.

This isn’t to say children need silence to learn. In fact, the opposite is true. They need a variety of sound environments and the ability to choose what their brains need in terms of auditory stimulation. Some students need noise to focus, some students need silence and each preference is affected by the type of learning they are being challenged to do.

Sound environments are more than just how loud the class is getting. It’s about the quality of the sounds. Squeaky brakes every three minutes, loud air-conditioning, background music that works for some and not others and irregular bangs and crashes all impact on a child’s ability to learn.

Teachers can allow students to get excited in their lessons and make noise appropriately, but keep some muffled headphones in your classroom for when students want to screen out sound.

Our auditory processing network is the first and largest information gathering system in our brains. Music can enhance the biological building blocks for language. Music both prepares children for learning to read, and supports them as they continue their reading journey.

Unfortunately, it’s disadvantaged students who are least likely to have music learning in their schools. Yet research shows they could benefit the most from music learning.

As we look to ways to improve the reading outcomes of our young children, more music education in our preschools and primary schools may be one way clear way forward.![]()

Anita Collins, Adjunct assistant professor, University of Canberra and Misty Adoniou, Associate Professor in Language, Literacy and TESL, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Jane Herbert, University of Wollongong and Elisabeth Duursma, University of Wollongong

We often hear about the benefits of reading storybooks at bedtime for promoting vocabulary, early literacy skills, and a good relationship with your child. But the experts haven’t been in your home, and your child requests the same book every single night, sometimes multiple times a night. You both know all the words off by heart.

Given activities occurring just before sleep are particularly well-remembered by young children, you might wonder if all this repetition is beneficial. The answer is yes. Your child is showing they enjoy this story, but also that they are still learning from the pictures, words, and the interactions you have as you read this book together.

Read more:

Six things you can do to get boys reading more

A preference for familiarity, rather than novelty, is commonly reported at young ages, and reflects an early stage in the learning process. For example, young infants prefer faces that are the same gender and ethnicity as their caregiver.

With age and experience, the child’s interests shift to novelty seeking. By four to five months, novel faces are more interesting than the now highly familiar caregiver face.

But even three-day olds prefer looking at a novel face if they’re repeatedly shown a picture of their mother’s face. So once infants have encoded enough information about an image, they’re ready to move on to new experiences.

Your child’s age affects the rate at which they will learn and remember information from your shared book-reading. Two key principles of memory development are that younger children require longer to encode information than older children, and they forget faster.

For example, one-year olds learn a sequence of new actions twice as fast as six-month olds. And while a 1.5-year old typically remembers a sequence of new actions for two weeks, two-year olds remember for three months.

Two dimensional information sources, like books and videos, are however harder to learn from than direct experiences. Repeated exposure helps children encode and remember from these sources.

Being read the same story four times rather than two times improved 1.5- and two-year olds’ accuracy in reproducing the actions needed to make a toy rattle. Similarly, doubling exposure to a video demonstration for 12- to 21-month olds improved their memory of the target actions.

Repeated readings of the same storybook also help children learn novel words, particularly for children aged three to five years.

Read more:

Children prefer to read books on paper rather than screens

Repetition aids learning complex information by increasing opportunities for the information to be encoded, allowing your child to focus on different elements of the experience, and providing opportunities to ask questions and connect concepts together through discussion.

You might not think storybooks are complicated, but they contain 50% more rare words than prime-time television and even college students’ conversations. When was the last time you used the word giraffe in a conversation with a colleague? Learning all this information takes time.

The established learning benefits of repetition mean this technique has become an integral feature in the design of some educational television programs. To reinforce its curriculum, the same episode of Blue’s Clues is repeated every day for a week, and a consistent structure is provided across episodes.

Five consecutive days of viewing the same Blue’s Clues episode increased three to five year olds’ comprehension of the content and increased interaction with the program, compared to viewing the program only once. Across repetitions, children were learning how to view television programs and to transfer knowledge to new episodes and series. The same process will likely occur with storybook repetition.

The next time that familiar book is requested again, remember this is an important step in your child’s learning journey. You can support further learning opportunities within this familiar context by focusing on something new with each retelling.

One day look more closely at the pictures, the next day focus on the text or have your child fill in words. Relate the story to real events in your child’s world. This type of broader context talk is more challenging and further promotes children’s cognitive skills.

You can also build on their interests by offering books from the same author or around a similar topic. If your child currently loves Where is the Green Sheep? look at other books by Mem Fox, maybe Bonnie and Ben rhyme again (there are sheep in there too). Offer a wide variety of books, including information books which give more insight into a particular topic but use quite different story structures and more complex words.

Remember, this phase will pass. One day there will be a new favourite and the current one, love it or loathe it, will be back on the bookshelf.

Read more:

Reading teaching in schools can kill a love for books

![]()

Jane Herbert, Associate Professor in Developmental Psychology, University of Wollongong and Elisabeth Duursma, Senior Lecturer in Early Childhood Literacy, University of Wollongong

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Misty Adoniou, University of Canberra; Brian Cambourne, University of Wollongong, and Robyn Ewing, University of Sydney

The Victorian Coalition has promised $2.8 million for “decodable readers” for schools if they win the upcoming election.

Money for books must surely be a good thing. But what exactly is a “decodable reader”? After all, surely all books are decodable. If they weren’t decodable they would be unreadable.

Read more:

Lost for words: why the best literacy approaches are not reaching the classroom

The Australian curriculum provides a clear definition of decoding:

A process of working out the meaning of words in a text. In decoding, readers draw on contextual, vocabulary, grammatical and phonic knowledge.

However the Victorian Coalition is defining decoding as “sounding out letters”. As their policy platform states:

Decodable books are designed to align with explicit, systematic phonics instruction. They are simple stories constructed using almost exclusively words that are phonetically decodable, using letters and letter-groups that children have learned in phonics lessons.

The “decodable readers” they are funding are books that are contrived to help children practise a particular letter-sound pattern taught as part of a synthetic phonics program.

For example, the following sentences are from a decodable reader designed to focus on the consonants “N” and “P” and short vowel /a/

Nan and a pan.

Pap and a pan.

Nan and Pap can nap.

Books like this have no storyline; they are equally nonsensical whether you start on the first page, or begin on the last page and read backwards.

While they may teach the phonics skills “N” and “P”, they don’t teach children the other important decoding skills of grammar and vocabulary.

And as many a parent will testify, they don’t teach the joy of reading.

Read more:

The way we teach most children to read sets them up to fail

Meaning and vocabulary development are not the focus of decodable readers. Yet, research shows the importance of vocabulary for successful reading.

Students need to add 3,000 words a year to their vocabulary to be able to read and write successfully at their year level.

Limited vocabulary in books translates to lack of vocabulary growth.

Supporters of decodable readers are hopeful these books will support students with reading difficulties, by focusing closely on the sounds in words. However, focusing on sounds alone is not sufficient to support a struggling reader.

The reality is all children learning to read need to listen to, and read books that are written with rich vocabulary, varied sentence structures and interesting content knowledge that encourages them to use their imagination.

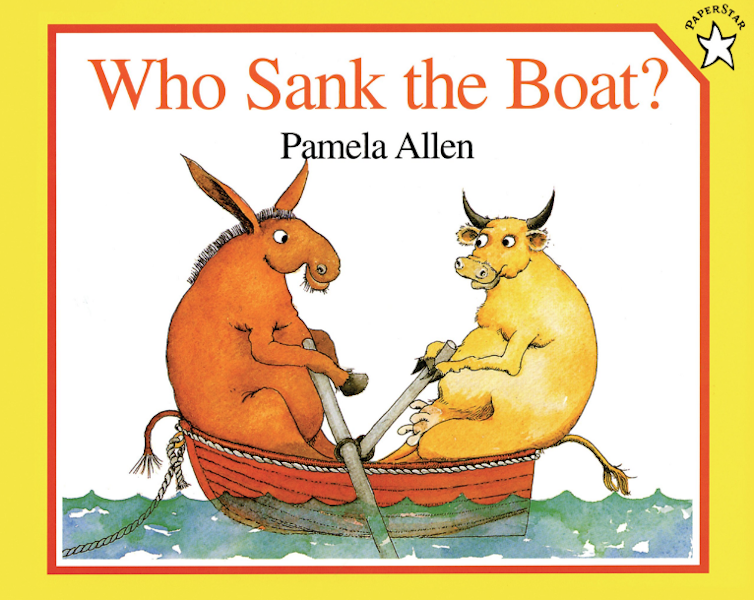

Compare the text about Pan and Nap with the opening lines of Pamela Allen’s very popular story Who Sank the Boat?:

Beside the sea, on Mr Peffer’s place, there lived

a cow, a donkey, a sheep, a pig, and a tiny little mouse.

They were good friends and one sunny morning, for no particular reason,

they decided to go for a row on the bay.

Do you know who sank the boat?

This book immediately engages children and asks them to question, imagine and help solve a problem. Children always ask for this book to be read again and again and they enjoy joining in. They learn new vocabulary and incidentally learn about complex sentence structures, which they emulate in their oral language and story writing.

Read more:

A balanced approach is best for teaching kids how to read

Using rich authentic texts supports all the decoding skills described in the Australian curriculum – phonics, vocabulary and grammar.

In Pamela Allen’s story above, we can look at the word “bay” and notice the parts /b/ – /ay/, which help us to say and spell the word. What happens if we change the beginning – how many other words could we write and read? For example, day, say, play, and so on.

We can look at the “frequent” words. These are the words that we can’t always “sound out” but which make up the 100 most frequent words in English. For example, do, you, they, were, the.

These words are very important to teach children, as these 100 words make up 50% of all written language.

We can develop their vocabularies with words and phrases such as “for no particular reason”, “decided” and “beside” .

We can introduce them to beautifully literate sentence structures, for example,

“Beside the sea, on Mr Peffer’s place, there lived a cow, a donkey, a sheep, a pig, and a tiny little mouse”.

Decodable readers can only do the phonics part of the reading puzzle. They are a very inefficient way to teach reading.

When teaching children to read, we hope they will learn reading is pleasurable and can help them to make sense of their lives and those around them.

The strategies children are taught to use when first learning to read greatly influence what strategies they use in later years.

When children are taught to focus solely on letter-sound matching to read the words of decodable readers, they often continue in later years to over-rely on this strategy, even with other kinds of texts. This causes inaccurate, slow, laborious reading, which leads to frustration and a lack of motivation for reading.

A book must be worth reading and give children the opportunity to learn the full range of strategies needed to read any text.

Children who grow up with real books, with rich vocabularies, beautiful prose and genuine storylines reach a higher level of education than those who do not have such access, regardless of nationality, parents’ level of education or socioeconomic status.

And yet it’s children from disadvantaged backgrounds who are less likely to have access to these books in their homes. It’s crucial schools fill the gap.

A$2.8 million spent on beautifully written books to fill Victorian classroom libraries would be a far more effective use of the education budget.![]()

Misty Adoniou, Associate Professor in Language, Literacy and TESL, University of Canberra; Brian Cambourne, Principal Fellow, Faculty of Education, University of Wollongong, and Robyn Ewing, Professor of Teacher Education and the Arts, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Margaret Kristin Merga, Curtin University

The OECD consistently finds girls perform significantly better than boys in reading. This gap can also be observed across the Australian NAPLAN reading data.

Research suggests reading more can improve literacy outcomes across a range of indicators. But girls typically read more frequently than boys, and have a more positive attitude toward reading.

Read more:

Research shows the importance of parents reading with children – even after children can read

Parents read more with their daughters. This sends a strong and early message that books are for girls, as well as equipping girls with a significant advantage. Recent research found even though boys read less frequently than girls, girls receive more encouragement to read from their parents.

So how can parents and educators help bridge the gap for boys’ literacy?

To improve boys’ literacy outcomes, parents and educators may look for ways to connect boys with reading. This had led to discussion about the importance of promoting so-called “boy-friendly” books that boys are supposedly “drawn to”, which are typically assumed to be non-fiction works, as it’s regularly contended that boys prefer to read non-fiction.

But this contention is not typically supported by recent quantitative research. For example, OECD and my own research suggests boys are more likely to choose to read fiction than non-fiction. Encouraging all boys to read non-fiction under the assumption this meets an imagined uniform preference can actually lead to negative outcomes.

Firstly, the reading of fiction is more consistently associated with literacy benefit than non-fiction in areas such as verbal ability and reading performance. When we tell boys non-fiction books are for them, this may steer them away from a more beneficial text type. This is counterproductive if we’re doing so in order to improve their literacy.

Secondly, recent research suggests non-fiction readers tend to read less frequently than fiction readers. So, if we want to increase boys’ reading frequency, engaging them in fiction may be more effective.

We may also be encouraged to steer boys toward comic books. While children can benefit from exposure to diverse text types, the reading of comic books, e-mails and social networking posts, newspapers, magazines and text-messages is not associated with the same level of literacy benefit.

Read more:

Five tips to help you make the most of reading to your children

In addition, recent research supports the relationship between reading fiction and the development of pro-social characteristics such as empathy and perspective taking. So reading fiction can help students to meet the Personal and Social Capability in the Australian Curriculum, among other general capabilities. Instead of buying into stereotypes, we should aim to meet our children’s individual reading interests and encourage a reading diet that includes fiction.

Here are six strategies you can use to connect boys with books and increase their reading engagement:

just as your interests and views are not identical to all those of the same age and gender, boys have diverse interests and tastes. These don’t necessarily stay static over time. To match them with reading material they’re really interested in, initiate regular discussions about reading for pleasure, in order to keep up with their interests

schools should provide access to libraries during class time throughout the years of schooling. Girls may be more likely to visit a library in their free time than boys, and as children move through the years of schooling they may receive less access to libraries during class time, curtailing boys’ access to books. Access to books is essential to promote reading

keep reading to and with boys for as long as possible, as many boys find it enjoyable and beneficial beyond the early years

provide opportunities and expectations for silent reading at home and at school, despite competing demands on time

keep paper books available. Boys who are daily readers are even less likely to choose to read on screens than girls. The assumption that boys prefer to read on screens is not supported by research

promote reading as an enjoyable and acceptable pastime by being a great role model. Let your children or students see you read for pleasure.

As a final comment, the OECD note:

Although girls have higher mean reading performance, enjoy reading more and are more aware of effective strategies to summarise information than boys, the differences within genders are far greater than those between the genders.

So, parents and educators seeking to support the literacy attainment of young people through increased reading engagement should focus on meeting the needs of all disengaged and struggling learners, regardless of gender.![]()

Margaret Kristin Merga, Senior Lecturer in Education, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that takes a look at how to read books.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2018/10/03/how-to-read-a-book/

You must be logged in to post a comment.