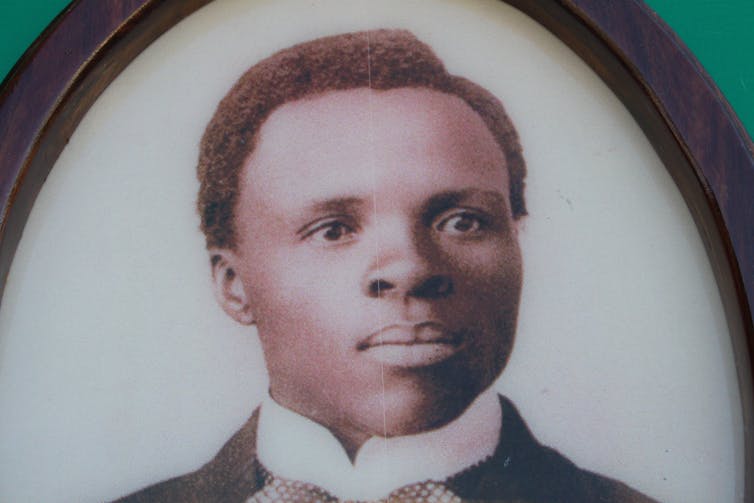

flowcomm/Flickr, CC BY-SA

Jenny Boźena du Preez, Nelson Mandela University

Solomon T. Plaatje was born in 1876 and was one of the founding members of South Africa’s current ruling party, the African National Congress.

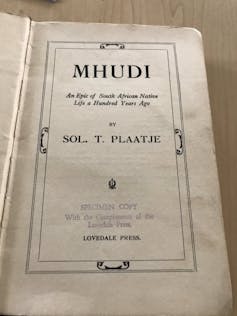

He was a politician, intellectual, journalist and author of the seminal Native Life in South Africa. He was also a writer of fiction. His first and only novel, Mhudi, was written in 1920 and published a decade later.

Despite being the first novel by a Black South African in English, it had little impact on the literary landscape of the country at the time. However, over the past century, the novel has garnered great interest from scholars.

One notable aspect of the novel is that it centres a woman as its protagonist – the Mhudi of the title – and her role in resistance. Her proactive, adventurous, quick-witted character has led a number of scholars to consider the novel from a feminist perspective. In fact, it has been described as “ahead of its time” for its portrayal of women in an era when women had few rights, and Black women almost none.

When working on my chapter for the new book, Sol Plaatje’s Mhudi: History, Criticism, Celebration, I found that most feminist scholarship on the novel has focused on the individual character of Mhudi. So, I turned my attention to Mhudi’s solidarity with other women and what this might tell us about Plaatje’s view of the nature of political struggle.

What the novel’s about

Mhudi takes place against the backdrop of fictionalised versions of actual historical events in what is today called South Africa. The action of the novel is set off by King Mzilikazi’s massacre of the Barolong people at Kunana in 1832. Mzilikazi was king of the Matabele, a group of people today known as the Ndebele and living mostly in Zimbabwe. The Barolong, now called the Rolong, are a clan of the Tswana people living largely in Botswana.

Mhudi, a young Barolong woman, manages to escape the massacre with her life, but believes she is the only one of her people left alive. However, after wandering in the wilderness, she meets a young Barolong man, Ra-Thaga, and they get married. The story follows the couple on several perilous adventures, in which Mhudi frequently saves Ra-Thaga through common sense and uncommon bravery, until they are united with the other surviving Barolong.

Read more:

Anniversaries spark renewed readings of South Africa’s celebrated Sol Plaatje

Determined to defeat the Matabele, the Barolong form a coalition with the Boers, the white, Afrikaans-speaking farmers descended from Dutch settlers. Ra-Thaga takes part in the successful battle, but is wounded. Mhudi, seeing this in a dream, leaves her children with her cousin and travels to aid him. On her way, she befriends Hannetjie, a young Boer woman, and Umnandi, the favourite wife of Mzilikazi, who fled her home because of the scheming of her co-wives. The Matabele routed, Mhudi and Ra-Thaga happily return home.

Women’s solidarity

The most obvious of women’s solidarities in the novel are those with their husbands. The second most apparent are the friendships Mhudi forms across racial and ethnic boundaries with Umnandi and Hannetjie. While personal, these relationships also have political implications.

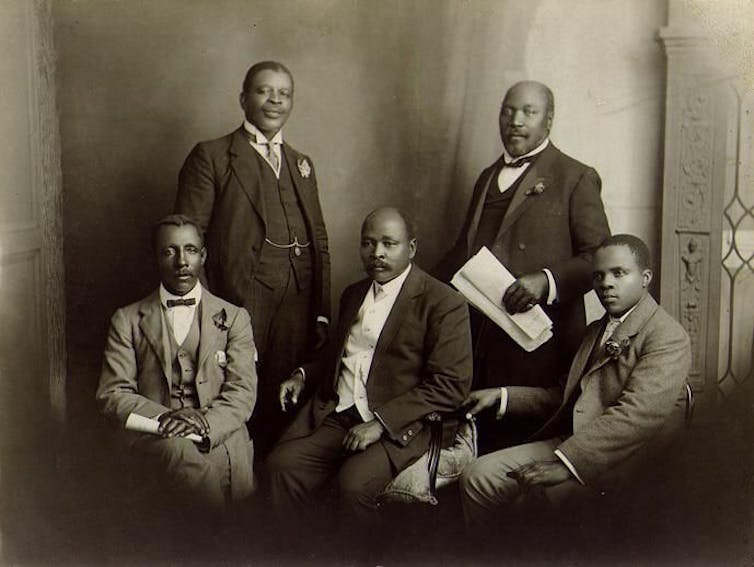

Blessing Kgasa/Kanye Records Centre/Twitter

Mhudi’s relationships with these two women allow her to see the humanity of the Matabele and the Boers, who she had, until this point, seen as inhumane and violent. This is because these two women also express their disapproval for unjust violence and suffering.

Mhudi’s friendships with these two exceptional women and their significance has been discussed in feminist analyses of the novel. However, the collective solidarity that Mhudi has with Barolong women has not really been considered. And yet, this is important in how we understand Plaatje’s view of resistance. We can see this idea of collective solidarity – standing together – in a story Mhudi tells Ra-Thaga about how she escaped being killed by a lion when she was a girl.

The story goes that Mhudi is out picking berries with a number of other Barolong girls and comes face-to-face with a lion. The other girls initially run away, but when they see Mhudi is paralysed with fright they run back and manage to scare off the lion. The fact that the girls are willing to return to Mhudi, even to die alongside her, suggests a deep sense of solidarity and commitment, the kind that arguably binds together successful political movements.

The individual and the collective

The reception of the lion story among the Barolong shows a tension between the collective and the individual. Ra-Thaga knows the story well. Mhudi’s bravery has been celebrated and she has even been called a heroine. However, the collective role of the girls in saving her has been lost in the story’s retelling.

Read more:

Conversing across a century with thinker, author and politician Sol T Plaatje

We might understand this as a critique of individual heroism in stories of resistance (especially if we read the lion as a symbol of British and other imperialism) to the exclusion of the recognition of the collective that makes resistance possible.

It’s significant that Mhudi’s most productive relationships are with Barolong women from her community. Her relationship with Hannetjie has no real political impact besides shifting Mhudi’s view of the Boers. Despite herself and Hannetjie sharing a horror over the treatment of the servants, their friendship does not result in any material resistance to injustice.

Her relationship with Umnandi creates a deeper solidarity, as they both promise to use their influence on men to promote peace. However, it is her cousin looking after her children that allows her to make the journey that leads to her relationships with Umnandi and Hannetjie and to assisting her husband.

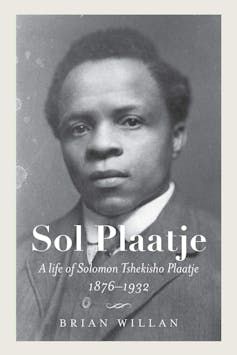

Jacana Media

Therefore, I read in Mhudi a sense of the importance of collective, communal forms of solidarity. Even when resistance requires alliances across racial, ethnic and gender boundaries, it is the communal solidarities women form that allow for individual and boundary-crossing solidarities to exist.

This might serve as a reminder to consider how we intrepret Plaatje’s place in the history of struggle in South Africa. While Plaatje is a fascinating and notable figure, whatever legacy he has left us was created and preserved through solidarities with others.

This article is based on Jenny Boźena du Preez’s chapter in the book Sol Plaatje’s Mhudi: History, Criticism, Celebration published by Jacana Media.![]()

Jenny Boźena du Preez, Postdoctoral Fellow, Nelson Mandela University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.