AP Photo/Tony Dejak

Rachel D. Williams, Simmons University; Christine D’Arpa, Wayne State University, and Noah Lenstra, University of North Carolina – Greensboro

CC BY-ND

America’s public library workers have adjusted and expanded their services throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

In addition to initiating curbside pickup options, they’re doing many things to support their local communities, such as extending free Wi-Fi outside library walls, becoming vaccination sites, hosting drive-through food pantries in library parking lots and establishing virtual programs for all ages, including everything from story times to Zoom sessions on grieving and funerals.

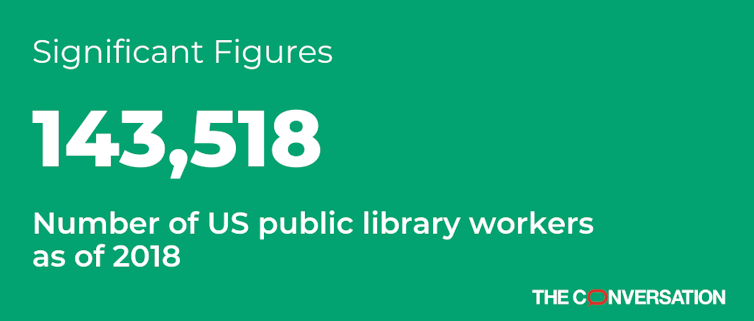

In 2018, there were 143,518 library workers in the United States, according to data collected by the Institute of Museum and Library Services. While newer data isn’t available, the number is probably lower now, and recent history suggests more library jobs may be on the chopping block in the near future.

As library and information science researchers, we are concerned about library worker job insecurity.

During the Great Recession, the economic downturn between late 2007 and mid-2009, thousands of librarians and other library staff lost their jobs. As local governments cut spending on libraries, the size of that workforce shrank to 137,369 in 2012 from 145,499 in 2008.

Many library workers actively supported the recovery from that economic crisis in many creative ways. Some loaned patrons professional attire to wear for job interviews. Others helped local unemployed people gain basic financial literacy and digital skills.

Unfortunately, many of the Great Recession’s job losses were never completely overcome. There were about 2,000 fewer library workers in 2018 than in 2008, at the height of the crisis.

Library workers are again losing their jobs despite the important roles that libraries are playing today. According to preliminary data and news coverage collected by the Tracking Library Layoffs initiative, it’s clear that not all of the library workers furloughed since March 2020, when virtually all U.S. libraries were closed amid lockdowns, have been brought back on staff.

At the same time, many library workers have had to directly engage in person with the public throughout the pandemic, exposing them to health risks.

There are steps the federal government could take to protect the nation’s libraries.

For example, after Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and Hurricane Sandy in 2012, the Federal Emergency Management Agency recognized libraries among essential services. The federal government has not taken this step so far during the coronavirus pandemic.

Among other things, lacking this designation may have made it more difficult for librarians and other library staff members to get COVID-19 vaccines.

To date, the federal coronavirus relief packages have included a total of about US$250 million to support public libraries. These funds, distributed to state library agencies, amount to approximately $14,304 – about 1.7% of their annual revenue – for each of the nation’s 17,478 library branches and bookmobiles. We suspect that this infusion of cash will fall short of what’s needed to help public libraries and their workers recover from the tumult caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

[Over 100,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]![]()

Rachel D. Williams, Assistant Professor of Library and Information Science, Simmons University; Christine D’Arpa, Assistant Professor of Library and Information Sciences, Wayne State University, and Noah Lenstra, Assistant Professor of Library and Information Science, University of North Carolina – Greensboro

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.